Bilboes

Bilboes (always plural) or grillos are iron restraints normally placed on a person's ankles. They have commonly been used as leg shackles to restrain prisoners for different purposes until the modern ages. Bilboes were also used on slave ships, such as the Henrietta Marie. According to legend, the device was invented in Bilbao, Basque Country within Spain, and was imported into England by the ships of the Spanish Armada for use on prospective English prisoners. However, the Oxford English Dictionary notes that the term was used in English well before then.

Bilboes consist of a pair of "U"-shaped iron bars (shackles) with holes in the ends, through which an iron rod is inserted. The rod mostly has a large knob on one end, and a slot in the other end into which a wedge or a padlock is driven to secure the assembly. Bilboes occur in different sizes, ranging from regular large ones to smaller sizes particularly fitting women's ankles and even sizes to restrain the wrists. The rod can also be fastened to a wall or a rigid trestle as it was mostly used in prisons. This way the person is restrained to stay put, while only allowing movement of the feet sideways inside the limited range the rod allows for.[1]

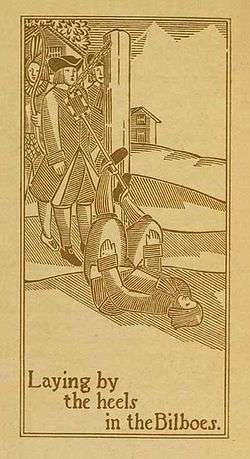

Bilboes used as public punishment in former times combined physical discomfort with public humiliation. The person was often restrained barefoot, which added to the humiliation. They were popular in England and America in the colonial and early revolutionary periods (such as in the Massachusetts Bay Colony). They were used in England to "punyssche transgressours ageynste ye Kinges Maiesties lawes". Bilboes appear occasionally in literature, including Hamlet (Act V, Scene 2: "Methought I lay worse than the mutinies in the bilboes") and the journals of Captain Cook.[2]

A notable case of excessive use is documented from Trinidad under British administration by governor Thomas Picton during the criminal procedure against eighteen-year-old Louisa Calderon in 1801. The former maid of governor Picton was accused of theft from his household and interrogated. She was also subjected to the picket torture, which first led to an extorted confession. Subsequently she was left restrained in bilboes over the continuous period of eight months while the legal inquest was in progress. The shackles were rigidly fastened to the wall of her confinement cell, so she was forced to remain in one place for the entire duration of her imprisonment. The charges were eventually dropped, so Louisa Calderon was released from her incarceration and the bilboes were taken off after months of being incessantly restrained. This excessive form of incarceration along with the preceding torture was later assessed as inhumane in a juridic reappraisal.[3]

Bilboes were used to restrain slaves on slave ships. Components forming more than eighty bilboes have been recovered from the Henrietta Marie, an English slave ship that was wrecked in the Florida Keys in 1700 after delivering slaves to Jamaica. Bilboes were also found in the Molasses Reef Wreck, a Spanish wreck in the Turks and Caicos Islands from very early in the 16th century, which may have been a slave ship hunting Lucayans in the Bahamas. Bilboes were used to fasten two slaves together, so that the eighty-plus bilboes found on the Henrietta Marie would have restrained up to 160 slaves. Bilboes were usually not placed on every slave transported, nor were they left on for all of a voyage. Only the slaves that were strongest and presumably most likely to revolt or escape were kept in bilboes for all of a voyage.[1]

References

- Malcom, Corey (October 1998). "The Iron Bilboes of the Henrietta Marie" (PDF). The Navigator: Newsletter of the Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society. 13 (10). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2012.

- Earle, Alice Morse (1896). Curious Punishments of Bygone Days. at Project Gutenberg

- "THOMAS PICTON, ESQ". The Newgate Calendar. Retrieved 2014-02-22.