Benoît de Boigne

Benoît Leborgne (24 March 1751 – 21 June 1830), better known as Count Benoît de Boigne or General Count de Boigne, was a military adventurer from the Duchy of Savoy, who made his fortune and name in India with the Marathas. He was also named president of the general council of the French département of Mont-Blanc by Napoleon I.

The son of shopkeepers, Leborgne was a career military man. He was trained in European regiments and then became a success in India in the service of Mahadaji Sindhia of Gwalior in central India, who ruled over the Maratha Empire. Sindhia entrusted him with the creation and organization of an army. He became its general, and trained and commanded a force of nearly 100,000 men organized on the European model, which allowed the Maratha Empire to dominate north India and be the last native state of Hindustan to resist the British Empire. Along with his career in the army, Benoît de Boigne also worked in commerce and administration. Among other titles, he became a Jaghirdar which gave him enormous land holdings in India.

After a turbulent life, Benoît de Boigne returned to Europe, first to England, where he married a French emigrant after having repudiated his first, Persian wife; then to France during the Consulate, and finally back to Savoy (then an independent kingdom). He devoted the end of his life to charity in Chambéry, where he was born. The king of Piedmont-Sardinia gave him the title of Count.

Early life

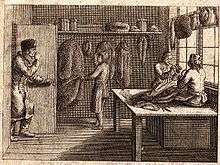

He was born at Chambéry in Savoy on 24 March 1751, the son of a fur merchant. His paternal grandfather, born at Burneuil in Picardy, moved to Chambéry, in the Dukedom of Savoy, at the beginning of the 18th century. In 1709 the grandfather married Claudine Latoud, born in 1682. They had thirteen children, of whom only four reached the age of twenty, and opened up a fur shop on rue Tupin in Chambéry.

This shop made an impression on the young Benoît Leborgne. In his Mémoires, he wrote that he was fascinated by the exotic sign outside the shop. It was brightly colored and featured wild animals including lions, elephants, panthers and tigers, with the motto underneath: "You can go ahead and try something else, you will all come to Leborgne, the fur dealer." The child's imagination was stimulated, and he kept asking his parents and grandparents about the animals. He wanted to know more about the far-off countries where they lived.

His father, Jean-Baptiste Leborgne, born in 1718, frequently traveled on business to wild-fur markets and brought back bearskins, fox, beaver, and marten furs, and many other animal pelts. Sometimes he traveled as far as Scotland, and he dreamed of going to the Indies. His wife was against this, but he passed his dream on to his son.

His mother, Hélène Gabet, born in 1744, was born into a family of notaries who worked closely with the Savoy Senate. Although her family was not happy about her marriage to a fur merchant, they accepted it. Benoît was the third of the couple's seven children – three boys and three girls. One of his brothers, Antoine-François, became a monk at the monastery of Grande Chartreuse, but influenced by ideas of the French Revolution, he left and later married. His son Joseph became a notable lawyer in Turin. Benoît, who had been destined for the law, was not the only adventurer in his family. His brother Claude went to Santo Domingo, in what is now the Dominican Republic. Claude was imprisoned in Paris during the Reign of Terror, and later became a deputy for the island of Santo Domingo (now called Hispaniola) in the Council of Five Hundred under the French Directory. During the first empire (of Napoleon) he was named to office in Paris and took the title of Baron. This title was given to him, like the title of Count given to his brother Benoît Leborgne, by the king of Piedmont-Sardinia, in 1816. At the age of 17, Benoît Leborgne fought a duel with a Piedmont officer and wounded him. This cost him his chance to join the Brigade de Savoie. He therefore enlisted in the French Army.

Early military career

Leborgne began his military career in the north of France in 1768, as an ordinary soldier in Louis XV's Irish Regiment, directed by Lord Clare and quartered in Flanders. This regiment was made up mostly of Irish emigrants who did not want to serve the British; at this time Irish Catholics were disenfranchised in their own country under the anti-Catholic penal laws. During this period, many Irishmen left Ireland for the Catholic countries of Europe or for North America. Here Benoît Leborgne learned English and the rudiments of army life. He listened to the military tales of his superior officers, especially those of Major Daniel Charles O'Connell about India. Many years later, he met O'Connell again in England and was introduced through him to his future wife Adèle.

While in the Irish Regiment, Leborgne took part in several campaigns which took him across Europe, as well as to islands in the Indian Ocean, including Bourbon Island (now called Réunion). In 1773, at age 22, Benoît Leborgne resigned from the army. Lord Clare and Colonel Meade had died, bringing changes to the Regiment. Europe was at peace and his chances of promotion had become slim.

The Russian-Turkish war

As he was leaving the Irish Regiment, young Leborgne learned from the newspapers that Prince Fyodor Grigoryevich Orlov of Russia was raising, in the name of Empress Catherine II of Russia, a Greek regiment to attack the Ottoman Empire. At the time, Russia was attempting to extend its territory to acquire a port on the Black Sea, and was using the anti-Turkish sentiments of people under Ottoman domination to aid its project. Leborgne saw a chance of advancement and adventure. He went back to Chambéry for a short time and got a letter of recommendation to Prince Orlov through the cousin of a client of his mother's, who was a close acquaintance of the prince. First Leborgne went to Turin, which was then the capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia, where he met the cousin. Afterwards, he went to the Veneto, then crossed to the Aegean Sea. He arrived in Paros, where Prince Orlov was forming his Greek-Russian regiment. The prince accepted him and he joined the ranks.

Leborgne quickly saw that his enlistment was a mistake. The prince confided to him his doubts on the future military campaign and its chances of victory. These pessimistic forecasts were quickly confirmed. On the island of Tenedos, the Turks were victorious, and the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) ended for Leborgne with his capture by the Turks, although some members of his regiment succeeded in escaping. He was taken to Constantinople and became a slave, where he had to do menial work for many weeks. However, his owner soon noticed that he could speak English and put him to work dealing with the British Lord Algernon Percy. Percy, surprised to see a European slave, was able to procure Leborgne's freedom after a week of negotiations, with the aid of the British embassy.

Preparations for India

Lord Percy took Leborgne as a guide through the Greek islands back to Paros, where Leborgne officially resigned from his regiment. He was free again, but had only his last pay received from before his resignation. He travelled to Smyrna (now Izmir), which at the time was a prosperous, booming city. There, Leborgne met merchants from many countries, including India, which was believed to hold much wealth, like the diamonds of Golconda and the sapphires of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Some of these merchants told him their theories about the existence of trade routes passing north of India, in upper Kashmir or along the glaciers of Karakoram. He also learned that many rajahs regularly sought out European officers to organize and command their armies.

These stories persuaded Leborgne to try his chances. Through his friend Lord Percy, he was able to get letters of recommendation to Lord Hastings and Lord Macartney in India. He also asked for letters of recommendation from Prince Orlov in Saint Petersburg, where the prince obtained an audience for him with the Empress Catherine II. Leborgne explained to her he wanted to discover new trade routes to India passing through Afghanistan or Kashmir. The empress, wishing to extend her power to Afghanistan, agreed to help him. At the end of 1777, Leborgne began a journey with many detours. After having tried to travel by land, he gave up and decided to reach India by ship. However, during the voyage to Egypt, a storm washed away all his possessions, including the letters of recommendation. Not wishing to abandon his journey, Leborgne went to the British consulate in Egypt and met Sir Baldwin. After a number of discussions, he was advised to take service in the British East India Company, and he was given a letter of recommendation to this effect.

Military glory and fortune in India

In the late 18th century, the mighty Maratha Empire was gradually collapsing. The British were triumphing over their Portuguese, French, and Dutch rivals in India, where all the countries had hastened to install trading posts. The British East India Company was the most powerful military and economic force and came to dominate India, including its princes. The British established a powerful colonial administration placed under the direct responsibility of the British Crown. Many Europeans benefited from the political confusion of India, offering their services as mercenaries to Indian princes and becoming rich merchants themselves. The Europeans had the advantage of military experience in the European wars, knowledge of arms production, especially cannons, and of new military strategies.

Arrival in India

In 1778, Leborgne arrived at the Indian port of Madras (now Chennai). He was poor and to make a living, taught fencing. While teaching, he met a nephew of the British governor of the city, Sir Thomas Rumbold. He was offered a position as an officer in the 6th battalion of sepoys, a troop of local inhabitants raised by the Company. He accepted, and gradually learned the local customs and began training the sepoys. He lived in Madras for four years, but became restless. He was ambitious, and decided to go to Delhi in the north of India, where the Moghul Emperor Shah Alam II held court. The Marathas and Rajputs were employing Europeans and giving them the command of their armies. The new governor, Lord MacCartney, gave Leborgne letters of recommendation to the governor of the province of Bengal, in Calcutta, and Leborgne sailed there.

He met governor Warren Hastings, who approved his projects of exploration. Again he was given letters of recommendation, this time to Asaf-Ud-Dowlah, the Nawab of Oudh, in Lucknow. The rajah was a vassal of the British. In January 1783, Leborgne started his trip. He traveled through many extremely poor villages, learning about the culture and religion of India and noted the different Muslim and Hindu neighborhoods in various places.

Arrival in Lucknow

In Lucknow, Leborgne was received by the nabab Asaf-ud-Daulah and was invited to live with Colonel Pollier, in the service of the Company. As Middleton, an Englishman present when Leborgne met the nabab, explained to him afterward, this invitation was in fact an order; if he refused he would have been thrown in prison. Colonel Antoine Polier, a Swiss, received him warmly. Leborgne discovered that Lucknow had many European residents. He met two who spoke French. The first, Claude Martin, was from Lyons and had made his fortune in India; the second, Drugeon, was from Savoy like himself. The nabab gave Leborgne a kelat, richly decorated with gold and diamonds, along with letters of exchange for Kandahar and Kabul, and 12,000 rupees. The nabab kept Leborgne, with many others, as a privileged captive for five months. Polier explained to Leborgne that although he had been given the letters of exchange, he would have to be patient. While waiting, Leborgne began to learn Persian and Hindi.

He also changed his name at this time to sound more aristocratic. From then on he called himself de Boigne, inspired by the English pronunciation of his name (English-speakers could not pronounce the "r" correctly). Along with Claude Martin, his friend from Lyons, de Boigne occupied himself by selling silver jewelry, silk carpets, and arms enameled in gold. He also went tiger-hunting on elephant-back with Polier and the nabab.

Leaving Lucknow for Delhi

In August 1783, de Boigne received permission to leave Oudh and went north to search for new trade routes. His journey by horse led him to Delhi in the company of Polier, who also had to go there for business. During the trip, de Boigne saw the Taj Mahal and other Indian sights, including various smaller kingdoms and tribes. In Delhi, an Englishman named Anderson offered to get de Boigne an audience with Emperor Shah Alam, whose court was at the Red Fort. During this audience, de Boigne told the emperor about his proposal to seek new trade routes, but the emperor put off any decision ("We'll see"). De Boigne waited in Delhi, hoping for a favorable answer. However, circumstances were about to change. The day after the audience, an imperial edict gave Mahadji Sindhia the government of the provinces of Delhi and Agra. In other words, Sindhia became the imperial regent and the real power, while Emperor Shah Alam, without being deposed, was now only a figurehead. In 1790, de Boigne summarized Indian politics of the time:

"The respect toward the house of Timur [the Moghul dynasty] is so strong that even though the whole subcontinent has been withdrawn from its authority, no prince of India has taken the title of sovereign. Sindhia shared this respect, and Shah Alam [Shah Alam II] was still seated on the Moghul throne, and everything done in his name."

In the midst of these political upheavals, de Boigne met Armand de Levassoult, a European friend of Polier. Levassoult was in the service of Begum Joanna Nobilis (Begum Samru of Sardana, d. 1836), an influential woman respected by the emperor, but also by his Maratha adversaries. For a few days, de Boigne found himself in Delhi unable to go north, since the local administration did not give him permission. However, he met Levassoult again and Levassoult invited him to go to Sindhia's camp with him.

Doubted by Marathas, betrayed by Jaipur

The Marathas had set up camp to besiege the citadel of Gwalior, in which a Scot named George Sangster, whom de Boigne had met in Lucknow, was commanding the garrison. When Levassoult and de Boigne arrived in the Maratha camp, they received a warm welcome. Levassoult presented his friend as the bravest of soldiers, and de Boigne was given a tent. However, while he was away from it, his baggage was stolen, and with it the precious letters of exchange of Hastings and also the letter for Kabul and Peshawar. He soon learned that this theft had been ordered by Sindhia himself, who wanted to know more about this suspect European. De Boigne, wanting revenge, decided to send a discreet message to Sangster in the besieged citadel and proposed an attack on the Maratha camp. But while he was waiting for the answer, he was called by an enraged Sindhia who had discovered the message. De Boigne had to explain that his act was a response to the theft of his baggage and letters of exchange.

Sindhia discussed with De Boigne about an expedition to the north of India and a resulting possible invasion by the Afghans. He then offered to de Boigne the command of the camp guard, which de Boigne refused. Vexed, Sindhia dismissed him without returning his precious papers. This misadventure showed de Boigne that his project of exploration was unpopular among Indians, and he decided to abandon it. His argument with Sindhia came to the ears of Sindhia's enemies, first to those of the Rajah of Jaipur, who was looking for a European officer to form two battalions. De Boigne accepted the offer and returned to Lucknow to raise and train the troops. The British, suspicious, asked de Boigne to explain himself to Hastings, who, after hearing his intentions, allowed him to continue. Once the battalions were recruited and operational, de Boigne and his men started for Jaipur. However, en route they were stopped at Dholpur by a local petty lord whose fortress blocked the only passage. After they gave him a ransom, he allowed them to pass. This episode displeased the Rajah of Jaipur, who dismissed de Boigne without any compensation, while keeping the two new battalions.

In the service of the Maratha empire

After a time wandering, de Boigne again met his friend Levassoult, who introduced him to the Catholic convert Begum Joanna. She confided to him that Sindhia, the Maratha chief wanted him back. Although Sindhia had been mistrustful of de Boigne's projects of exploration, and in spite of their argument over the confiscated baggage, Sindhia had been impressed with de Boigne's two European-trained battalions, which contrasted sharply with his own troops. De Boigne finally agreed to enter the service of the Marathas. He was put in charge of organizing a cannon foundry in Agra, as well as equipping and arming 7000 men in two battalions. De Boigne from this time quickly became an influential man. One of the first actions under his command was the October 1783 capture of the citadel of Kalinjar in the region of Bundelkhand. The rajah of this region ended up parleying with de Boigne, which allowed Sindhia to enter Delhi as its master. The Maratha chief named himself "Column of the Empire" and Prime Minister. His seizure of power led to many conflicts and betrayals.

Over the next few years there were many battles among Marathas, Mughals, Kachwahas and Rathores. At the battles of Lalsot (May 1787) and of Chaksana (24 April 1788), de Boigne and his two battalions proved their worth by holding the field when the Marathas were losing. The year 1788 was especially turbulent. On August 10, Gholam Kadir had the Emperor Shah Alam's eyes torn out. On August 14, the Maratha army, allied with the army of Begum Joanna and of that of her old enemy Ismail Beg, entered Delhi, retaking the town it had once lost. Kadir escaped but was captured, and the Marathas killed him gruesomely, among other tortures putting out his eyes and cutting off his ears and nose. His corpse was then given to the emperor. Once more Mahadji Sindhia had triumphed and was now the true power in India. It was at this time that Benoît de Boigne proposed to Sindhia the creation of a brigade of 10,000 men in order to consolidate his conquest of India. Sindhia refused because his treasury could not afford it, but also because he had doubts about the superiority of the artillery-infantry combination, as opposed to the cavalry that had been the main weapon of the Maratha armies. This refusal caused a new dispute between the two men, and Benoît de Boigne resigned. Once more unemployed, he returned to Lucknow. [1]

Commercial life and first marriage

Back in Lucknow, Benoît de Boigne found his old friends Antoine-Louis Polier and Claude Martin. Martin persuaded de Boigne to work with him in trade. His military skills were useful, for at the time, Indian trade routes were dangerous, and even warehouses in the cities were sometimes robbed. Claude Martin and Benoît de Boigne built a warehouse inside an old fort. It included saferooms and a trained armed guard to watch it. Quickly, this business became successful. De Boigne also carried on a trade in precious stones, copper, gold, silver, indigo, cashmere shawls, silks, and spices. He became rich and now owned a luxurious house with many servants, a wine-cellar, and valuable horses. At this time, de Boigne fell in love with a young woman from Delhi named Noor Begum ("light" in Arabic). She was the daughter of a colonel in the Persian Guard of the Great Moghul, whom he had met to discuss a simple lawsuit. The same day, he asked the colonel for his daughter's hand in marriage. After a long discussion, the father accepted, even though de Boigne refused to convert to Islam as was normally required for the husband of a Muslim woman. De Boigne wooed Noor, who could speak perfect English. The wedding lasted several days, first in Delhi, with sumptuous feasts, then more simply in Lucknow. The couple had two children, a daughter born in 1790 and a son in 1791.

A general in the service of the Maratha empire, with the title of jaghir

In 1788, Sindhia sent a discreet message to de Boigne. Sindhia wished to unite north and northwest India. At the time, the Rajputs and the Marathas had a tense relationship. The Marathas were levying the peasants with more taxes. Sindhia succeeded in convincing de Boigne to return to his service. He asked him to organize a brigade of 12,000 men within a year (January 1789-January 1790). De Boigne became commander-in-chief and general, the highest title under "rajah." To be able to pay his men, Sindhia gave his new general a jaghir, a fief given for the lifetime of its holder, against a payment in return to the imperial treasury. At the death of its holder, the jaghir reverted to another deserving officer. The revenues from the jaghir allowed the officer to pay his men. Benoît de Boigne received the Doab, a region of plains in Uttar Pradesh. This plain was covered with jungle and included several towns like Meerut, Koal and Aligarh. De Boigne had to use some of his savings to renovate this new land. He built a citadel and stores. The military camp built by de Boigne was very European. To work with the new brigade, he hired Drugeon from Savoy, Sangster from Scotland, John Hessing, a Dutchman, as well as Frémont and Pierre Cuillier-Perron, two Frenchmen, a German named Anthony Pohlmann and an Italian, Michael Filoze. The administrative and military language became French, and the flag of Savoy, red with a white cross, became the ensign of the new brigade. Because of his high rank, Sindhia obliged de Boigne to have a personal guard, and de Boigne chose 400 Sikhs and Persians. The brigade itself consisted of approximately nine battalions of infantry, each with its own artillery and baggage train. The brigade artillery included about fifty bronze cannons, of which half were big-caliber and transported by oxen, and the other pieces by elephants and camels. De Boigne's brigade also invented a weapon composed of six musket-barrels joined together. The brigade was supported by 3000 elite cavalry, 5000 servants, team drovers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and others. A novelty for India was the ambulance corps, in charge of rescuing wounded soldiers, including enemy soldiers. De Boigne also acquired a parade elephant named Bhopal. The brigade was ready in 1790.

Military campaigns and victories

Starting in 1790, the brigade had to face Rajputs, Ismail Beg, and the rajahs of Bikaner and Jaipur. De Boigne decided to attack this coalition by surprise on May 23. De Boigne demonstrated his military talent by gaining one victory after another. The East India Company began to become concerned about this new Maratha army, dangerous to their domination. Within six months of 1790, in a hostile, hilly terrain, de Boigne's brigade defeated 100,000 men, confiscated 200 camels and 200 cannons, many bazaars, and fifty elephants. The Maratha army attacked and took seventeen fortresses by siege. It won several decisive battles, among which the most difficult were the battles of Patan, Mairtah, and Ajmer. The Rajputs recognized the authority of Sindhia as prime minister. The Marathas were now the masters of northern and northwestern India. During these military campaigns, de Boigne continued his commercial association with Claude Martin from a distance. Sindhia, more powerful than ever, asked de Boigne to raise two more brigades. These were formed and their command was given by de Boigne to Frémont and Perron, assisted by Drugeon.

For a while, de Boigne could enjoy his new social position and the respect that his victories had won him, as well as the reforms which he had undertaken in his jaghir. But the calm was of short duration, and military campaigns started up again. The Marathas of central India became a threat. Due to internal differences, a new coalition of Holkar and Sindhia's enemy Ismail Beg, menaced the territory of Sindhia in northern India, and in spite of diplomatic negotiations and promises of imperial titles, there was a battle of Lakhari in 1793 between Holkar-Ismail Beg and Sindhia. De Boigne's brigades won and captured Ismail Beg, but his life was spared because de Boigne admired his brave spirit. De Boigne now attacked Holkar and after a fourth battle, the most exciting and dangerous, according to de Boigne, his troops won another victory. However, de Boigne was weary of war. The rajah of Jaipur, now in a position of weakness, preferred peace. De Boigne was rewarded by Sindhia with an enlargement of the jaghir, and also gave a jaghir to de Boigne's son, only an infant at the time.

Trusted by Maratha chiefs. European events

Sindhia had become the most powerful man in India, with many enemies. As they were not able to beat him militarily, the Maratha chief faced conspiracies, intrigue and treason. De Boigne was a faithful follower and Sindhia trusted him and made him a confidant. De Boigne now was running imperial affairs for Sindhia in north and northwestern India. The minister Gopal Rao, whose brother had been engaged in a famous plot with Nana Farnavis (Nana Fadnavis), came to Aligarh to visit de Boigne to show his loyalty to Sindhia. But while India was now a confederation under the Maratha authority, the situation in Europe was changing profoundly. The French Revolution had overturned the equilibrium in Europe, and also in Europe's colonial empires. On November 12, 1792, a Savoy assembly proclaimed its unity with France. Until 1815, de Boigne was now considered a Frenchman like any other. The brigades of the Maratha army under de Boigne's command were under European officers now divided by the political situation in Europe: one of the two French officers was a royalist and the other supported the revolution. De Boigne tried to keep his army out of European politics. He was more worried about the situation of Sindhia, who was still in Poona. Sindhia ordered him to send help, as he had to struggle against British intrigues. De Boigne sent him 10,000 men under the command of Perron.

On February 12, 1794, Sindhia died of high fever. De Boigne remained faithful to Daulat Rao Sindhia, the nephew and legitimate heir of Sindhia. De Boigne soon realized that the political situation had changed. His ideal of India as a confederation of free states would never come to pass. Sindhia's successor was less capable than his predecessor. In 1795, after twenty years in India, and in worsening health, de Boigne left his command, installing Perron in his place, and prepared his departure for Europe. At the end of his career in India, he was head of an army of almost 100,000 men, organized on the European model. The Maratha confederation was therefore the last indigenous state of Hindustan to resist the British. In November 1796 de Boigne left India, accompanied by his family and his most faithful Indian servants. He sold his personal guard to the British, with the consent of his men, for a price equivalent to 900,000 Francs Germinal.

Return to Europe and second marriage

Benoît de Boigne left for England, where he installed his household near London. Although he had been born a Savoyard, the Revolution had made him a Frenchman, and therefore a potential enemy of the British. His wealth and his letters of credit were held in abeyance at the bank. However, his military prowess was known to many British who had campaigned in India, some of whom had dined with him in India. This sympathy allowed de Boigne to take British nationality on January 1, 1798. The nationality was conditional upon his remaining in Britain or its colonies. Wishing to leave London, de Boigne acquired a house in the English countryside, in Dorsetshire. He considered going back to Chambéry, his native town, but the political situation was too uncertain. He also thought of entering politics, but his position was not good enough for the British parliament, since the parties expected candidates to have gone to the best British schools, have well-connected friends, and also to have a wife who could carry on diplomatic conversation and organize parties and receptions. De Boigne had his family christened, and Noor became Hélène. Although his seat was in the country, he was near London and went there often. He met many French emigrants, all waiting to be able to go back to France. In 1798, de Boigne met a Mademoiselle d'Osmond, sixteen years old. He repudiated his first wife, who had not been able to adapt to British customs and had become more and more distant, returning to her Indian habits. De Boigne was now completely taken by his new love. Not being legally married to Hélène under British law, he agreed to give her alimony and engaged a tutor for their children. On June 11, 1798, he married Adèle d'Osmond.

Unhappy second marriage; discovery of France under the Consulate

His second wife, born in 1781, was an emigrant from a penniless, though noble, old family from Normandy. De Boigne did not reveal his own lowly origins before the marriage. He seems to have wished, after his adventurous life, to start a family and establish himself in Europe through the help of his wife's high-placed relations. But from the beginning, the marriage was not a success. De Boigne had a hard time adapting to European manners after so long in India, and the 30-year difference in age between him and his wife added to the difficulty. He was jealous. He also now took opium to assuage the pain of his dysentery, and his wife and her family claimed he abused it. During this period, France was under the Consulate, and many French emigrants returned to France. De Boigne decided to go back as well, and in 1802 he settled in Paris, where the consul Napoleon Bonaparte was enjoying great popularity. De Boigne's wife went back to live with her parents. On April 30, 1802, de Boigne discovered from Drugeon, who had stayed in India, that Perron had become an important person there, but that Perron was greedy for money and seized his friend's property to get de Boigne's money and accelerate its decline.

In Paris, de Boigne became friends with General Paul Thiébault, who asked him several times to meet Napoleon so that he could become an officer in the French army. However, de Boigne, who was now in his fifties, did not want to return to his former rank of colonel, under the orders of younger men. Although he refused, the offer was renewed. In 1803, Napoleon offered a new proposition to Benoît de Boigne. He asked him to take command of Russian and French troops who would reach India through Afghanistan and chase off the British. But nothing came of this. Benoît de Boigne bought the Château de Beauregard, La Celle-Saint-Cloud for his wife, and she moved in on November 2, 1804. The property was ceded to Francesco Borghèse, Prince Aldobrandini of the House of Borghese, on November 14, 1812, in exchange for a house in Châtenay (now Châtenay-Malabry).

Final return to Savoy

Benoît de Boigne returned to Savoy definitively in 1807. There, he had himself called "General de Boigne." He lived alone in the château of Buisson-Rond near Chambéry, which he had bought in 1802 and appointed luxuriously for his young wife. But she continued to live in the Paris region, where she lived in the château of Beauregard and then of Châtenay. In this Parisian life she found the material for her celebrated Mémoires, which were published in 1907. The Comtesse de Boigne rarely came to Buisson-Rond, although she occasionally gave urbane receptions during the summer on her way home from taking the waters at Aix, in the company of her friends Madame Récamier, Madame de Staël, Adrien de Montmorency (Anne Adrien Pierre de Montmorency-Laval), and Benjamin Constant.

Having returned from the isle of Réunion, Benoît de Boigne received the title of Field Marshal on October 20, 1814, and the Croix de Saint-Louis (Order of Saint Louis) on December 6. His wife was pleased. On February 27, 1815, Louis XVIII gave him the Legion of Honor for services rendered as President of the Conseil général du département du Mont-Blanc. De Boigne was a fervent royalist, and ardent partisan of the Savoy government. Victor Emmanuel II of Italy, king of Sardinia and Savoy, gave him the title of Count in 1816, and Charles Felix of Sardinia conferred upon him the Grand Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus. In 1814 and 1816 he was named General in France and in Savoy.

During the last years of his life, Benoît de Boigne occupied himself in managing his immense fortune. He bought much land in the vicinity of Chambéry and of Geneva, and also in the west of the modern département of Savoie, including, in 1816, the château de Lucey. He spent much of his time on the development of his native city. He was a member of the city council of Chambéry in 1816. Although he no longer served in the military, he received the title of lieutenant-general in the armies of the king of Sardinia in 1822. On December 26, 1824, he was elected to the Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Belles-Lettres of Savoy, with the academic title "Effectif."

From 1814 until his death, de Boigne made many donations to the city of Chambéry, financing public and religious organizations, for welfare, education, and public works. He had no children with Adèle d'Osmond, so he made the decision to legitimize and naturalize his son Charles-Alexandre from his first marriage to Hélène (Noor). On June 21, 1830, Benoît de Boigne died in Chambéry. He was buried inside the church of Saint-Pierre-le-Lémenc. A funeral oration was given for him on August 19, 1830, in the metropolitan church of Chambéry, by the Canon Vibert, pro-vicar-general of the diocese and member of the royal academic society of Savoy.

Descendants of Benoît de Boigne

Charles-Alexandre de Boigne was born in Delhi, India in 1791. He married Césarine Viallet de Montbel in 1816. The marriage had been encouraged by his father. Césarine Viallet de Montbel was from a large Savoy family who had been parliamentarians and later ennobled. They had thirteen children. Charles-Alexandre, educated in England, had studied law, but spent most of his life as a minor courtier at the Savoy court, managing his land and inheritance. He was assisted by Thomas Morand, a Chambéry notary who had been chosen by Benoît de Boigne. Charles-Alexandre also had to liquidate the foundations and donations of his father. Charles-Alexandre died on July 23, 1853. His son Ernest acceded to the title. Ernest married Delphine de Sabran-Pontevès. Ernest de Boigne became captain of the firemen of the city of Chambéry, but soon became involved in politics. He was elected to the Savoy parliament, then became a deputy to the legislative body in 1860. He was twice reelected, as a conservative, in 1863 and 1869. He was decorated with the Legion of Honor. At the fall of the Second Empire, he lost his election in 1877. He became the mayor of Lucey. He died in 1895 at Buisson-Rond.

Benefactor of Chambéry

At his death, Benoît de Boigne left a fortune estimated at 20 million French francs of the time. Altogether, his donations to his native city amounted to about 3,484,850 francs. He left a permanent fund of 6500 pounds yearly to the metropolitan church of Chambéry for, among other things, the choir. He gave a second fund of 1250 pounds to the Compagnie des nobles Chevaliers-Tireurs-à-l'Arc (Company of noble knight archers).

De Boigne gave many donations for charity, including giving beds to hospitals. He donated 22,400 francs for three hospital beds at the Hôtel-Dieu, a charity hospital, and later gave 24,000 francs for another four beds for poor, sick foreign travelers of any nation or religion. He paid 63,000 francs for the construction of various buildings at the Hôtel-Dieu of Chambéry, and gave a beggars' home the sum of 649,150 francs. He founded an old age home, the Maison de Saint-Benoît, which cost him 900,000 francs. He also paid for a place in the orphanage for 7300 francs, and ten beds at the charity hospital, for patients with contagious illnesses, who could not be admitted to Hôtel-Dieu. De Boigne also gave a trust fund of 1650 pounds a year, about 33,000 francs, to help poor prisoners every week with laundry and food. He gave another perpetual trust of 1200 pounds or 24,000 francs to the poor "shameful" of the city, to be distributed at their homes. Finally, he left a trust fund of 1200 pounds to the firemen of Chambéry to help the sick and wounded. De Boigne gave 30,000 francs to build the church of the Capucins, and 60,000 francs to build a theater. Among his other numerous donations, two were important. One was 320,000 francs for various works, as well as the ownership without usufruct of the property of Châtenay. The second donation was for 300,000 francs to demolish the cabornes [stone huts] and open up a wide avenue across the city. He also gave 30,000 francs for the repair of the city hall and 5000 francs for the bell-tower of Barberaz.

De Boigne also gave four major donations to education. He gave 270,000 francs to reorganize the collège of Chambéry; he gave a trust fund of 1000 pounds a year, 20,000 francs, to the Société royale académique de Chambéry for the encouragement of agriculture, arts, and letters; he gave two trust funds of 150 pounds apiece, or 3000 francs, to the Frères des Écoles chrétiennes (Brothers of Christian Schools) and to the Sisters of Saint Joseph. Both of these groups gave a free education to children, the first to poor children, the second to girls.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Benoît de Boigne. |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 139. This cites H. Compton, European Military Adventurers of Hindustan (1892).

- Young, Desmond - Fountain of the Elephants (London, Collins, 1959)

References

- Dalrymple, William (2002). White Mughals. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-655096-9.