Battle of Bang Bo (Zhennan Pass)

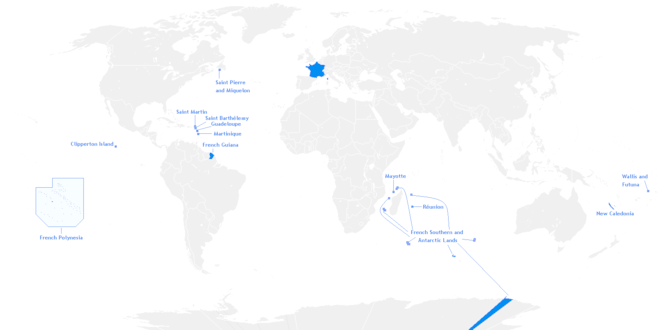

The Battle of Bang Bo, known in China as the battle of Zhennan Pass (Chinese: 鎮南關之役), was a major Chinese victory during the Sino-French War (August 1884–April 1885). The battle, fought on 23 and 24 March 1885 on the Tonkin-Guangxi border, saw the defeat of 1,500 soldiers of General François de Négrier's 2nd Brigade of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps by a Chinese army under the command of the Guangxi military commissioner Pan Dingxin (潘鼎新).[8]

| Battle of Bang Bo (Zhennan Pass) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tonkin Campaign, Sino-French War | |||||||

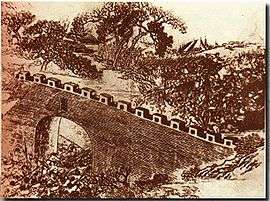

Chinese fortifications at Zhennan Pass | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1,500 men 10 guns |

Chinese claim: 40,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

74 killed 213 wounded[7] | 1,650 killed and wounded [7] | ||||||

The battle set the scene for the French retreat from Lạng Sơn on 28 March and the conclusion of the Sino-French War in early April in circumstances of considerable embarrassment for France.

The Tonkin military stalemate, March 1885

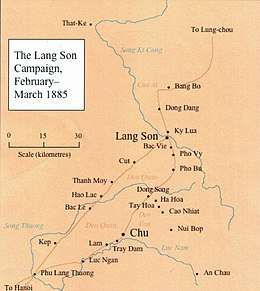

On 17 February 1885 General Louis Brière de l'Isle, the general-in-chief of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps, left Lạng Sơn with Lieutenant-Colonel Laurent Giovanninelli's 1st Brigade to relieve the Siege of Tuyên Quang. On 3 March, at the Battle of Hòa Mộc, Giovanninelli's men broke through a formidable Chinese blocking position and relieved the siege. Before his departure Brière de l'Isle ordered General François de Négrier, who remained at Lạng Sơn with the 2nd Brigade, to press on towards the Chinese border and expel the battered remnants of the Guangxi Army from Tonkinese soil. After resupplying the 2nd Brigade with food and ammunition, de Négrier defeated the Guangxi Army at the Battle of Đồng Đăng on 23 February and cleared it from Tonkinese territory. For good measure, the French crossed briefly into Guangxi province and blew up the 'Gate of China', an elaborate Chinese customs building on the Tonkin-Guangxi border. They were not strong enough to exploit this victory, however, and the 2nd Brigade returned to Lạng Sơn at the end of February.

By early March, in the wake of the French victories at Hòa Mộc and Dong Dang, the military situation in Tonkin had reached a temporary stalemate. Giovanninelli's 1st Brigade faced Tang Jingsong's Yunnan Army around Hưng Hóa and Tuyên Quang, while de Négrier's 2nd Brigade at Lạng Sơn faced Pan Dingxin's Guangxi Army. Neither Chinese army had any realistic prospect of launching an offensive for several weeks, while the two French brigades that had jointly captured Lạng Sơn in February were not strong enough to inflict a decisive defeat on either Chinese army separately.[9] Brière de l'Isle and de Négrier examined the possibility of crossing into Guangxi with the 2nd Brigade to capture the major Chinese military depot at Longzhou, but on 17 March Brière de l'Isle advised the army ministry in Paris that such an operation was beyond their strength. Substantial French reinforcements reached Tonkin in the middle of March, giving Brière de l'Isle a brief opportunity to break the stalemate. He moved the bulk of the reinforcements to Hưng Hóa to reinforce the 1st Brigade, intending to attack the Yunnan Army and drive it back beyond Yen Bay. While he and Giovanninelli drew up plans for a western offensive, he ordered de Négrier to keep the Chinese in respect around Lạng Sơn.

Meanwhile, behind the Chinese border, the Guangxi Army was also building up its strength. The French, whose Vietnamese spies in Longzhou had been conscientiously counting the company flags of every Chinese battalion that passed through the town, estimated on 17 March that they were facing a Chinese force of 40,000 men. This was an exaggeration, based on the assumption that each Chinese company was at full strength. In fact most of the Chinese commands were considerably understrength with 300 to 400 men, and the strength of the Guangxi Army at the Battle of Zhennan Pass was probably around a couple thousand men, while all of Longzhou had 25,000 to 30,000 men under arms. Even at this lower strength, it fearfully outnumbered the French.[10]

French and Chinese forces

By the middle of March nine separate Chinese military commands were massed close up to the Tonkinese border around the enormous entrenched camps of Yen Cua Ai and Bang Bo. There were six main Chinese concentrations. The entrenched camp of Yen Cua Ai was held by ten battalions under the command of Feng Zicai (冯子材) and a slightly smaller force under the command of Wang Xiaochi (王孝祺). These two commands numbered perhaps 7,500 men in all. Two to three kilometres behind Yen Cua Ai, around the village of Mufu, lay the commands of Su Yuanchun (苏元春) and Chen Jia (陳嘉), perhaps 7,000 men in all. Fifteen kilometres behind Mufu the commands of Jiang Zonghan (蔣宗汉) and Fang Yusheng (方友升), also 7,000 strong, were deployed around the village of Pingxiang (known to the French from its Vietnamese pronunciation as Binh Thuong). The commander of the Guangxi Army, Pan Dingxin (潘鼎新), lay at Haicun, 30 kilometres behind Mufu, with 3,500 men. Fifty kilometres to the west of Zhennanguan, 3,500 men under the command of Wei Gang (魏刚) were deployed around the village of Aiwa. Finally, fifteen kilometres to the east of Zhennanguan, just inside Tonkin, Wang Debang (王德榜) occupied the village of Cua Ai with 3,500 men.[11]

De Négrier's 2nd Brigade numbered around 1,500 men. The brigade's order of battle in March 1885 was as follows:

- 3rd Marching Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel Herbinger)

- 23rd Line Infantry Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Godart)

- 111th Line Infantry Battalion (chef de bataillon Faure)

- 143rd Line Infantry Battalion (chef de bataillon Farret)

- 4th Marching Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel Donnier)

- 2nd Foreign Legion Battalion (chef de bataillon Diguet)

- 3rd Foreign Legion Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Schoeffer)

- 2nd African Light Infantry Battalion (chef de bataillon Servière)

- 1st Battalion, 1st Tonkinese Rifle Regiment (chef de bataillon Jorna de Lacale)

- 3 artillery batteries (Captains Roperh, de Saxcé and Martin).

Roussel's battery, of Giovanninelli's 1st Brigade, was also at Lạng Sơn. The battery had lagged behind during the Lạng Sơn Campaign, and Giovanninelli had left it at Lạng Sơn when he set out with the 1st Brigade to relieve Tuyên Quang.

Not all of the 2nd Brigade was stationed at Lạng Sơn and immediately available for action. The four companies of Servière's 2nd African Battalion were echeloned between Lạng Sơn and Chu, guarding the vital French supply line up to Lạng Sơn and labouring to improve the miserable paths over which the expeditionary corps had advanced in February into a surfaced wagon road.

The battle of Bang Bo, 23 and 24 March 1885

On 22 March, Chinese forces under the command of Feng Zicai(冯子材) raided the French forward post at Dong Dang, a few kilometres north of Lạng Sơn. The French post, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Paul-Gustave Herbinger, was held by chef de battalion Diguet's 2nd Foreign Legion Battalion, and the legionnaires repelled the Chinese assault without difficulty. De Négrier, who had been forced to bring the bulk of the 2nd Brigade up from Lạng Sơn to support Herbinger, decided to hit back immediately. Hoping to take the Chinese by surprise, he decided to cross the frontier and attack the Guangxi Army in its entrenchments at Bang Bo, near the frontier pass of Zhennanguan. He had no intention of launching a major offensive into Guangxi. His aim, in the military phrase of the day, was simply to 'take some air' (se donner de l'air) around Dong Dang. After giving the Chinese a bloody nose at Bang Bo and clearing them away from the approaches to Dong Dang, he would return to Lạng Sơn with the 2nd Brigade.[12]

Leaving chef de bataillon Servière to hold Lạng Sơn with a single company of the 2nd African Battalion and Martin and Roussel's batteries, and stationing the 23rd Line Battalion at Dong Dang to protect his supply line, he advanced to the Chinese frontier at Zhennanguan on the morning of 23 March with a force of only 1,600 men and 10 guns (the 111th and 143rd Line Battalions, the 2nd and 3rd Legion Battalions and Roperh and de Saxcé's batteries). Substantial reinforcements for the 2nd Brigade were already on their way up to Lạng Sơn, but de Négrier decided not to wait for them. He judged it more important to attack the Chinese while they were still discouraged by Feng Zicai's repulse on 22 March.[13]

On 23 and 24 March the 2nd Brigade fought a fierce action with the Guangxi Army near Zhennanguan. This engagement, known as the Battle of Zhennan Pass in China, is normally called Bang Bo in European sources, after the name of a village in the centre of the Chinese position where the fighting was fiercest. The French took a number of outworks on 23 March, and defeated a hesitant Chinese counterattack against their right flank launched by Wang Debang from Cua Ai.[14]

On 24 March de Négrier attacked the Guangxi Army's main positions around Bang Bo. His plan called for a simultaneous frontal and rear attack on Feng Zicai's troops, who were holding a line of trenches in front of Bang Bo known to the French as the 'Long Trench'. The frontal attack would be delivered by Faure's 111th Battalion and the rear attack by Diguet's 2nd Legion Battalion and Farret's 143rd Battalion. Herbinger, who was instructed to guide Diguet and Farret to their attack positions, led the two battalions in a wide outflanking march in thick fog, and lost his way. De Négrier, unaware that Herbinger had failed to reach his positions, and mistaking a column of Chinese troops moving up to the Long Trench for Herbinger's two battalions, ordered chef de bataillon Faure's 111th Battalion to deliver its planned frontal attack.

The men of the 111th laid down their haversacks, formed up, and charged. The battalion came under heavy frontal fire from Feng Zicai's infantry and flanking fire from Chinese units on the nearby hills, and lost several company officers within seconds. Two of the four companies of the 111th Battalion reached the trench, but after a short spell of hand-to-hand fighting were thrown back by a Chinese counterattack led personally by Feng Zicai.

The senior surviving French company officer, Captain Verdier (who later wrote a detailed account of the campaign, La vérité sur la retraite de Lang-Son, under the pseudonym Jacques Harmant), was able to disengage and rally the battalion. The Chinese, intent on beheading the French wounded and plundering the abandoned French haversacks, did not seriously pursue the 111th Battalion, and Verdier was able to withdraw its shredded companies to safety.

Among the officers who fell during the 111th Battalion's attack on the Long Trench was 2nd Lieutenant Rene Normand, shot in the throat and mortally wounded. Normand had only recently arrived in Tonkin, and had distinguished himself on 10 February 1885 at the engagement at Pho Vy during the Lạng Sơn Campaign. A collection of his letters from Tonkin, including a number of vivid descriptions of the February campaign to capture Lạng Sơn, would be published posthumously in France in 1886.

On the right of the battlefield, the 143rd Battalion and 2nd Legion Battalion went into action several hours later than expected, and captured a Chinese fort. It was the only French success of the day. At 3 p.m. Pan Dingxin, seeing the 111th Battalion in full retreat and Herbinger's men exhausted from their exertions, counterattacked along the entire front. Herbinger's command was nearly cut off. Captain Gayon's company of the 143rd Battalion was surrounded by the Chinese. Captain Patrick Cotter, an Irish officer in Diguet's Legion battalion, ignored an order from Herbinger to leave Gayon to his fate and led his Legion company to the rescue. The legionnaires charged and successfully disengaged Gayon's men, but Cotter was killed in the attack. Diguet and Farret's battalions fell back by echelons, constantly turning and firing to keep the Chinese in respect.

Meanwhile, Schoeffer's 3rd Legion Battalion, which had been ordered to remain on Tonkinese soil around Dong Dang to protect the flanks of the French column, fought desperately to keep open a line of retreat for the 2nd Brigade. Schoeffer's men beat off strong Chinese attacks on both French flanks, enabling the other three infantry battalions and the two artillery batteries to make good their retreat. General de Négrier fought with the French rearguard, setting an example of personal courage, and the Chinese were unable to convert the French retreat into a rout. In the final flurry of action, just before nightfall, Captain Brunet of Schoeffer's battalion was shot dead.[15]

There were ominous scenes of disorder as the defeated French regrouped after the battle, and de Négrier had to intervene sharply to quell them. As the brigade's morale was precarious and ammunition was running short, de Négrier decided to fall back to Lạng Sơn. On the evening of 24 March the brigade marched back to Dong Dang, where it camped for the night. Hungry, exhausted, and shocked by their defeat, many French troops found it difficult to credit what had happened. Sergeant Maury of Diguet's 2nd Legion Battalion was overcome by a nervous reaction:

The night was very dark. The soldiers marched in complete silence. We felt cheated, ashamed, and angry. We were leaving behind us both victory and many of our friends. From time to time, in low murmurs, we established who was missing. Then we relapsed into the silence of mourning and the bitterness of loss. And so we reached Dong Dang, without being disturbed. We slept in the field hospital huts, after drinking some soup. We were harassed and hungry. We had not eaten all day, and had drunk nothing since morning except a single cup of coffee. In spite of my weariness, I spent a troubled night. My spirits were haunted by the day's memories, by images of the fighting and phantasms of our misfortunes. I was shaken with spasms. I trembled as I have never done on the battlefield. I lay down, but was unable to sleep.[16]

Casualties

Although the French made a fighting withdrawal from the battlefield and prevented the Chinese from piercing their line, casualties in the 2nd Brigade during the two-day battle were relatively heavy: 74 killed (including 7 officers) and 213 wounded (including 6 officers). Most of these casualties (70 killed and 188 wounded) were suffered on 24 March. The heaviest casualties were suffered by the 111th Battalion (31 killed and 58 wounded) and the 2nd Legion Battalion (12 killed and 68 wounded). There were also appreciable casualties in the 143rd Battalion (17 killed and 48 wounded) and the 3rd Legion Battalion (12 killed and 34 wounded).

The dead and mortally wounded officers included Captain Mailhat, Doctor Raynaud, Lieutenant Canin and 2nd Lieutenant Normand of the 111th Battalion, Lieutenant Thébaut of the 143rd Battalion, Captain Cotter of Diguet's Legion battalion and Captain Brunet of Schoeffer's Legion battalion. The wounded officers included chef de bataillon Tonnot of the Tonkinese Rifles, Lieutenant de Colomb of the 111th Battalion, Lieutenant Mangin and 2nd Lieutenant Bruneau of the 143rd Battalion and Lieutenant Durillon and 2nd Lieutenant Comignan of Diguet's battalion. Lieutenant Mangin died several days after the battle in Lạng Sơn, from shock following an operation to amputate a wounded limb.[17]

French estimates of Chinese casualties during the battle amounted to around 1,650 killed and wounded.[7]

French officers killed in action at Bang Bo, 24 March 1885

2nd Lieutenant Rene Normand, 111th Line Battalion

2nd Lieutenant Rene Normand, 111th Line Battalion Doctor Raynaud, 111th Line Battalion

Doctor Raynaud, 111th Line Battalion Captain Patrick Cotter, 2nd Legion Battalion

Captain Patrick Cotter, 2nd Legion Battalion Captain Brunet, 3rd Legion Battalion

Captain Brunet, 3rd Legion Battalion

Significance

The French defeat at Bang Bo on 24 March 1885 shook the nerve of several French politicians who had earlier supported France's war against the Qing Dynasty. More importantly, it convinced Lieutenant-Colonel Paul-Gustave Herbinger, de Négrier's second-in-command, that the 2nd Brigade was dangerously isolated at Lạng Sơn. On 28 March de Négrier was seriously wounded in the battle of Ky Lua,[18] in which the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps defeated an attack by the Guangxi Army on the defences of Lạng Sơn. Herbinger assumed command of the 2nd Brigade, and immediately ordered a retreat to Kép and Chu. The battle of Bang Bo therefore paved the way for the Retreat from Lạng Sơn and the collapse of Jules Ferry's administration on 30 March in the Tonkin Affair. The battle, before the war ended due to negotiations, made the Qing Dynasty seem to be almost victorious in the entire war in light of the French defeats at Zhennan and Langson.[1]

Movie

There is an action packed war movie, The War of Loong (2017) about Feng Zicai and the victory of Chinese troops in the Sino-French conflict (https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7345928/?ref_=ttpl_pl_tt).

See also

- French colonial empires

- Imperialism in Asia

- Jules Ferry

Notes

- John King Fairbank; Kwang-Ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett, eds. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800-1911. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 0-521-22029-7. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

In 1885, the Chinese defeated French forces at Chen-nan-kuan on the China-Annam border (23 March), and went on to recapture the important city of Langson and other points in Annam during the next two weeks. In the eyes of some, China was on the verge of victory when peace negotiations forced the cessation of hostilitties on 4 April 1885.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "清朝抗法英雄---苏元春".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Shipborne Weapons Defense Review(舰载武器·军事评论) 2013 Nov

- Armengaud, 40–58; Bonifacy, 23–6; Harmant, 211–35; Lecomte, 428–53 and 455; Maury, 185–203; Notes, 32–40

- Lecomte, 408–15; Thomazi, Conquête, 250–2; Histoire militaire, 110–11

- Lung Chang, 336

- Lung Chang, 334

- Armengaud, 39–40; Harmant, 203–9; Lecomte, 420–8; Notes, 31–2

- Lecomte, 425–8

- Lecomte, 428–35

- Lecomte, 450–2

- Maury, 202–3

- Bonifacy, 25–6; Lecomte, 453

- Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795-1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Retrieved 18 January 2012.

The Qing coury whole-heartedly supported the war, and from August to November 1884 the Chinese military prepared to enter the conflict. During the early months of 1885, the Chinese Army once again took the offensive as Beijing repteadly ordered it to march on Tonkin. However, the shortage of supplies, poor weather, and illness devastated the Chinese troops; one 2,000 man unit reportedly lost 1,500 men to disease. This situation led one Qing military official to warn that fully one-half of all reinforcements to Annam might succumb to the elements. The focus of the fighting soon revolved around Lạng Sơn, Pan Dingxin, the Governor of Guangxi, succeeded in establishing his headquarters there by early 1885. In February 1885 a French campaign forced Pan to retreat, and the French troops soon reoccupied the town. the French forces continued the offensive, an on 23 March they temporarily occupied and then hastily torched Zhennanguan, a town on the China-Annam border, before pulling back once again to Lạng Sơn. Spurred on by the French attack, General Feng Zicai led his troops southward against General François de Negerier's forces. The situation quickly became serious for the French, as their coolies deserted, interrupting the French supply lines, and ammunition began to run short. Even though the training of the Qing troops was inferior to the French and the Chinese officer corps was poor, their absolute number were greater. This precarious situation worsened for the French when General Negrier was wounded on 28 March. Lieutenant Colonel Paul Gustave Herbinger

References

- Armengaud, J. L., Lang-Son: journal des opérations qui ont précédé et suivi la prise de cette citadelle (Paris, 1901)

- Bonifacy, A propos d'une collection des peintures chinoises représentant divers épisodes de la guerre franco-chinoise de 1884–1885 (Hanoi, 1931)

- Harmant, J., La vérité sur la retraite de Lang-Son (Paris, 1892)

- Lecomte, J., Lang-Son: combats, retraite et négociations (Paris, 1895)

- Lung Chang [龍章], Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng [越南與中法戰爭, Vietnam and the Sino-French War] (Taipei, 1993)

- Maury, A., Mes campagnes au Tong-King (Lyons, undated)

- Notes sur la campagne du 3e bataillon de la légion étrangère au Tonkin (Paris, 1888)

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l'Indochine française (Hanoi, 1931)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)