Hispania Balearica

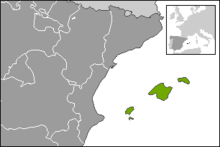

Hispania Balearica was a Roman province encompassing the Balearic Islands off the east coast of modern Spain. Formerly a part of Hispania Tarraconensis, Balearica gained its autonomy due to its geographic separation and economic independence from the mainland. The province included three major islands: Balearis Major (Majorca), Balearis Minor (Minorca), and Ebusus (Ibiza), and the small island of Colubraria or Ophiusa (Formentera). The islands were grouped as the Gymnesiae—Majorca and Minorca, and the Pityusae—Ibiza and Formentara.[1]

Conquest

Prior to the Roman occupation, the island was settled by the native Iberians (Talaiotic culture) and then by Phoenicians. The chief city of Minorca, Mago (Mahon) was founded by the Carthaginians. The islands, because of there being two excellent harbors on the largest island, Majorca, were a base for pirates from Sardinia and southern Gaul.[2] In 123 BC, a consul for that year, Q. Caecilius Metellus conquered the islands, easily routing and subduing the population. While not being a great victory militarily, Metellus received a triumph (parade) in 121 BC, and the surname Balearicus for bringing the islands into the Roman fold. Metellus founded the colonies of Palma and Pollentia on Majorca.[1] Pollentia became the capitol.

The Roman historians Florus, Orosius and Strabo provide good accounts of Balearicus' activities in 123–122.[3] Most importantly, they describe why the islands were invaded and why it happened in 123 BC. The answer is that the islands were suddenly overrun by pirates escaping the Roman campaigns in Transalpine Gaul in 126 and Sardinia in 125 BC. The Baleares were the last place for them to hide in the western Mediterranean. Control of the islands facilitated supply and trade from Hispania to Italy and vice versa, and they were also very fertile. In addition, 123 BC was the year that Gaius Gracchus held the powerful position of tribune. His fortune lay in clients he had in Hispania and Asia, so he had immense interest in seeing the islands captured and pacified. Although other motives – military, economic and political – may have played a subsidiary part in the decision, the islands were annexed in 123 BC to complete the pacification of Transalpine Gaul and Sardinia, which were resisting due to pirate influences.[4]

Economy

The territory was extremely valuable economically, so much so that Balearicus settled 3,000 ‘Romans’ on the islands in two settlements on Majorca, Palma, and Pollentia. The two settlements attest to the importance of the islands being firmly under Roman control. There is some debate as to where these settlers came from, as it is unlikely there were this many Roman civilians available and willing to colonize Majorca from the mainland at this date. The most likely explanation is that they were veterans from the wars in Hispania and Roman-Spanish hybridae.[5] Pollentia was located on the northern side and served as a port for vessels sailing to or from Gaul and Hispania Tarraconensis. The larger settlement, Palma, had a large and sheltered harbor perfectly situated for ships riding the trade winds from Baetica and Mauretania Caesariensis.

The Balearicas had much to trade. Pliny the Elder made a journey to the islands and described many features of their economy. They produced superior wheat compared to the rest of Spain (with Balearic wheat, one modius of grain yielded 35 pounds of bread; Baetic wheat, 22 pounds).[6] Also described was a trade in snails and fine wine that was well received by Romans, with Balearica soon becoming a center of wine production.[7] The sea was rich with oysters, tunny fish and mackerel. The bafii (dye-works) in the Baleares served the wool manufacturers of Baetica en route to markets in Italy and the east.[8] Stemming from this, the islands were rich in red ochre (earth colored with iron oxide), used to make red pigment for frescos.[9]

Slingers

Balearica was also known for its fighting slingers who were heavily recruited as mercenaries by the Romans. Their expertise as slingers is said by historians such as Posidorius, Diodoros and Strabo to be the result of their being made, while children, to earn their daily bread by slinging it off a post from many paces away depending on age.[10] Some slingers fought for Caesar in the Gallic War, and against him at Massalia.[11] The islands are named for their famed fighters - balearica, meaning "land of the slinger" (ballo) in Greek.

Government

Before being separated, Hispania Balearica was the fourth district of the Tarraconensis with a native local government headed by a council. It served to provide for local needs and as a link directly to Rome. During the reign of Augustus the Balearicans requested help in stopping a plague of rabbits for which the Emperor dispatched troops.[12]

Hispania Balearica became an independent province during the reign of Emperor Diocletian sometime after 284 AD. Under Diocletian, sweeping reforms of the provincial administration were enacted, designed to separate military and civic authority. Also, to reduce the power of other officials, the provinces were systematically reduced in size. All provinces were now under the direct control of the Emperor. All officials were chosen by him, including the legati pro praetore, men of praetorian rank who ran civic affairs in the province, and curators who ran the municipalities within provinces.[13] Balearica was separated because it was not reliant on the mainland for any staples and had special needs as a trading center that were more difficult to fulfil as a municipality than as a province. By the time of Diocletian, the islands' population was over 30,000, and they were granted their own Roman bishop in 418 AD.[14]

Decline and fall

In 426 the Vandals under King Gunderic captured Carthago Nova, the base of the "main naval force in the Western Mediterranean." That year or the next the king led a raid on Balearica.[15]:pp.60–61 In 455, following the death of Valentinian III, Gunderic's successor Gaiseric, now established in North Africa, annexed Balearica along with Corsica and Sardinia,[16] presumably to gain a naval base to attack Roman naval forces.[15]:p.153

Around 553 forces of the Byzantine general Belisarius recaptured the islands for the Empire,[17] where they remained until likely the tenth century when they were occupied by the Caliphate of Córdoba.[18]

References

- Smith, LLD, William (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: Walton and Maberly. Retrieved Sep 26, 2019.

- M. G. Morgan. ‘The Roman conquest of the Balearic Isles’, California Studies in Classical Antiquity, vol. 2, 1969, pp. 217.

- Badian, E. Foreign Clientelea. Oxford University press, 1958, pp. 182.

- Morgan. pp. 231.

- J.S. Richardson. Hispaniae: Spain and the development of Roman Imperialism. Cambridge University Press, 1986, pp. 163.

- J.J. Van Nostrand. ‘Roman Spain’, Economic Survey of Ancient Rome, vol. 3, 1937, pp. 176.

- Cambridge Ancient Histories. vol. X, pp. 408.

- J.J. Van Nostrand. pp. 218.

- I.L.S., pp. 1875.

- Morgan. pp. 219.

- Curchin, Leonard. Roman Spain: Conquest and Assimilation. Routledge Inc., 1991, pp. 101.

- Curchin, Leonard. Pp. 64.

- C.A.H., vol. IX, pp.347-48.

- Bouchier, E.S. Spain Under the Roman Empire. Oxford University Press, 1914, pp. 179.

- Hughes, Ian (2017). Gaiseric: The Vandal Who Destroyed Rome. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-78159-018-8. Retrieved Oct 2, 2019.

- Kulikowski, Michael (2019). The Tragedy of Empire. Cambridge, Ma: The Belknap Press. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-674-66013-7.

- Smith, William; Wace, Henry (1882). A Dictionary of Christian Biography, Literature, Sects and Doctrines: Hermogenes-Myensis. Little, Brown. p. 540. Retrieved Oct 2, 2019.

- Zavagno, Luca (2017). Cyprus Between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (ca. 600–800). Taylor & Francis. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-138-24331-6. Retrieved Oct 2, 2019.