Armenians in Egypt

Armenians in Egypt are a community with a long history. They are a minority with their own language, churches, and social institutions. The number of Armenians in Egypt has decreased due to migrations to other countries and integration into the rest of Egyptian society, including extensive intermarriage with Muslims and Christians. Today they number about 6000, much smaller than a few generations ago. They are concentrated in Cairo and Alexandria, the two largest cities. Economically the Egyptian Armenians have tended to be self-employed businessmen or craftsmen and to have more years of education than the Egyptian average.[1]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 6,500-12,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Cairo · Alexandria | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity: (Armenian Orthodox, Armenian Catholic, and some Protestants) |

| Part of a series on |

| Armenians |

|---|

|

| Armenian culture |

|

Architecture · Art Cuisine · Dance · Dress Literature · Music · History |

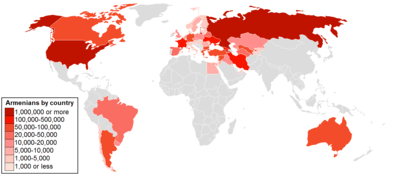

| By country or region |

|

Armenia · Artsakh See also Nagorno-Karabakh Armenian diaspora Russia · France · India United States · Iran · Georgia Azerbaijan · Argentina · Brazil Lebanon · Syria · Ukraine Poland · Canada · Australia Turkey · Greece · Cyprus Egypt · Singapore · Bangladesh |

| Subgroups |

| Hamshenis · Cherkesogai · Armeno-Tats · Lom people · Hayhurum |

| Religion |

|

Armenian Apostolic · Armenian Catholic Evangelical · Brotherhood · |

| Languages and dialects |

| Armenian: Eastern · Western |

| Persecution |

|

Genocide · Hamidian massacres Adana massacre · Anti-Armenianism Hidden Armenians |

History

Armenians in Egypt have had a presence since the 6th and 7th centuries.[2] The early Armenian migrants to Egypt were Muslims. A migration of Armenian Christians to Egypt started in the early 19th century, and another wave occurred in the early 20th century.

The presence of Muslim Armenians in Egypt is well documented during and after the Muslim conquest of Egypt. Islamized Armenians under Arab rule had visible military and government positions, such as governors, generals and viziers (and the more notable individuals are listed by name further below).[2]

Fatimid period

This was a prosperous period for the Armenians in Egypt, when they enjoyed commercial, cultural and religious freedom. Their numbers increased considerably as more migrants arrived from Syria and Palestine, fleeing the advance of the Seljuks westward during the second half of the 10th century. Armenian Muslims started their political life in 1074, with an estimated population of 30,000 (possibly as high as 100,000) Armenians living in Fatimid Caliphate at the time.[3] A series of viziers of Armenian origin shaped the history of the Fatimid Caliphate, beginning with Badr al-Jamali and his son al-Afdal Shahanshah, up until Tala'i ibn Ruzzik and his son Ruzzik ibn Tala'i.

Mamluk period

Nearly 10,000 Armenians were captured, during invasions of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, which took place between 1266 and 1375, and were brought to Egypt as mamluks or slave-soldiers.[4] They were employed in agriculture and as craftsmen. The youngest were educated in army camps following the Mameluke system, and later employed in the army and the palace.

At the beginning of the 14th century, a schism occurred in the Armenian church, which caused Patriarch Sargis of Jerusalem to request and obtain a firman from the Sultan Al-Malik Al-Nasir. This brought the Armenians within the Mamluk realm under the jurisdiction of the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem. The schismatic Armenians who came to Egypt were given permission to practice their religion freely. Their patriarch's authority over the Armenian community's private and public affairs was decisive. The churches and those who served them were supported by the generosity of the faithful and the revenues deriving from charitable foundations.

Mohamed Ali period

The reign of Muhammad Ali of Egypt (1805–1849) witnessed strong migration streams of Armenians to Egypt. Mohamed Ali hired Armenians in government positions, and the Armenians were given great opportunities to contribute to the socioeconomic development of Egypt.[2] The era of Mohamed Ali witnessed building Armenian churches in Egypt; one for the Armenian Orthodox and another one for the Armenian Catholics. The number of Armenians immigrants to Egypt around this time is estimated at 2,000.[5] Boghos Youssufian (1768–1844) was an Armenian banker and businessman. In 1837, Muhammad Ali appointed Boghos as head of the Diwan Al-Tijara (bureau of commerce) and overseer of other financial affairs for Mohamed Ali.

In 1876 the Armenian Nubar Nubarian (1825–1899) became the first Prime Minister in modern Egypt.

Starting from the 19th century Egypt became one of the centers of Armenian political and cultural life. Many prominent Armenians of that period, including Komitas, Andranik and Martiros Sarian visited Egypt. The Armenian General Benevolent Union was founded in Cairo in 1906. The first Armenian film with Armenian subject called "Haykakan Sinema" was produced in 1912 in Cairo by Armenian-Egyptian publisher Vahan Zartarian. The film was premiered in Cairo on March 13, 1913.[6]

Post-genocide (1915-1952)

The Armenian Genocide started on 24 April 1915 with the deportation of Armenian intellectuals. The Armenian communities in Egypt received some percentage of the refugees and survivors of the massacres in Turkey. The total number of Armenians in Egypt in 1917 was 12,854 inhabitants. They increased to reach its peak in 1927 census data where their total number was 17,188 inhabitants most of whom were concentrated in Cairo and Alexandria. Some independent estimates push the number of Armenians in Egypt to 40,000 inhabitants at the beginning of year 1952.[1]

Armenian community life in Egypt revolved around the Armenian Apostolic Church and, to a lesser extent, the Armenian Catholic Church. Over 80% of the adult Armenian population in Egypt worked as skilled craftsmen or in administrative positions, wholesale, retail and services. A very small number of Armenians, only around 5 per cent, worked as unskilled laborers; even fewer were landowners or farmers. Egyptian Armenians were relatively prosperous compared to Armenians in other Middle Eastern countries; of the 150,000 Middle Eastern Armenians who emigrated to Soviet Armenia between 1946–48, only 4,000 were Egyptian.[7]

After the 1952 revolution led by Gamal Abdel Nasser many Armenians began to emigrate to Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia.

After the 1952 Revolution

A reverse migration, not to the original homelands, but rather to the West, was observed among Armenian Egyptians starting in around 1956. 1956 saw the introduction of what are called the “Socialist Laws” in Egypt and the nationalization of many economic sectors under the Nasser regime. Since Armenian Egyptians at that time worked predominantly in the private sector and tended to monopolize basic professions and trade markets, the so-called Socialist Laws affected them more than those working in the government or in agriculture. Many migrants concluded – mistakenly or correctly – that they were threatened by the new policies of the Nasser regime and many left Egypt and migrated to the West. Since 1956 the total number of Armenian Egyptians has decreased. Accurate figures of how many left and how many are still there are not available since questions on ethnicity have not been included in censuses since the 1952 revolution.

Present day

Most Egyptian Armenians today, who are permanent residents of Egypt, were born in Egypt and are Egyptian citizens. Armenia to them is the collection of folkloric stories and cultural practices that each generation hands to its successor. Armenian Egyptians are full Egyptians with an extra cultural layer. They number around 6,000 and live primarily in Cairo.[1]

Today structures such as clubs, schools, and sports facilities reinforce communications among Armenian Egyptians and revive the heritage of their forefathers. In spite of these efforts, many Armenian Egyptians of the youngest generation (and who are mostly the result of marriages between the Armenian community and other Egyptians - whether Christian or Muslim) do not speak the Armenian language, or go to Armenian schools, and are not in touch with their heritage or community. The Armenian Church and the apolitical structure of the Armenian community have a very important role in unifying Armenians in Egypt. Unlike Armenian minorities in Syria and Lebanon, Armenian Egyptians stay out of local politics.

The Prelacy of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Egypt, which is under the jurisdiction of Holy Etchmiadzin, is the primary guardian of community assets such as endowments, real estate in the form of agricultural land, and other property bequeathed by generations of philanthropists.

Politics

Egyptian Armenians are very rarely involved in present-day Egyptian politics, unlike the Armenian minorities in Lebanon and Syria. However, many are employed in different political and apolitical Egyptian institutions. The Armenian Church and the apolitical structure of the institutions in the Egyptian Armenian community have a very important role in unifying the Armenians in Egypt.

Culture

The Armenian community operates a number of associations, including:

- The Armenian Red Cross Association

- The Armenian General Benevolent Union (founded in Egypt)

- Housaper Cultural Association.

The community has four social clubs in Cairo and two in Alexandria, in addition to three sporting clubs in the capital and two in Alexandria. There is one home for the elderly, and many activities for young people, including a dance troupe, Zankezour, a choir, Zevartnots, and a children's choir, Dzaghgasdan.

Journalism

Today, in Egypt, there are two daily papers and one weekly publication, all affiliated to Armenian political parties.

- Housaper, a daily belonging to the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Tashnag Party), was founded in 1913;

- Arev, a daily, put out by the Armenian Democratic Liberal Party (Ramgavar Party), was founded in 1915

- Tchahagir, a weekly founded in 1948 belonging to the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (Hentchag Party).

Periodicals and newsletters include:

- Arev Monthly, published 1997–2009 in Arabic as a supplement to Arev daily. It was published by the Armenian Democratic Liberal Party.

- Arek Monthly, started publishing in April 2010 in Arabic. It is published by the Armenian General Benevolent Union.

- AGBU Deghegadou, published since 1996 by the Armenian General Benevolent Union in Cairo as a newsletter covering AGBU's activities

- Dzidzernag, a musical quarterly supplement published by Arev Daily starting 2001

Sports

There are a number of Sports clubs including:

- Homenetmen Gamk, Alexanadria founded in 1912

- Homenetmen Ararat, Cairo founded in 1914

- AGBU Nubar, Alexandria founded in 1924

- AGBU Nubar, Cairo founded in 1958

- St. Theresa Club Cairo founded in 1969

Sports played include association football (soccer), basketball and table tennis. Almost all the clubs also have scouting activities.

Schools and institutions

The first Armenian school in Egypt, the Yeghiazarian Religious School, was established in 1828 at Bein Al-Sourein. In 1854, the school was moved to Darb Al-Geneina and the name was changed to Khorenian, after the Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi. In 1904, Nubar Pasha, an Armenian statesman, moved the Khorenian School to Boulaq. In 1907, he founded the Kalousdian Armenian School and kindergarten on Galaa Street (downtown Cairo), which is currently defunct. The second Armenian school in Egypt was founded in 1890 by Boghos Youssefian in Alexandria, and is called Boghossian School. The newest Armenian school is Nubarian in Heliopolis, founded in 1925 with a donation from Boghos Nubar. Now, Kalousdian school & Nubarian are merged as one school in Heliopolis area, Cairo.

The three Armenian schools in Egypt eventually integrate a K-12 program. Armenian 6 schools in Egypt are partially supported by the Prelacy of the Armenian Church in Egypt. Armenian education is very important in maintaining Armenian language among the Armenian community in Egypt. In Addition, Armenian language is the only language that Armenians use within their families and communities. The three Armenian schools in Egypt eventually integrated a secondary education programme; students who have graduated can immediately enter the Egyptian university system, after passing the official Thanawiya 'Amma (High School) exams.

Church

Armenian Egyptians are divided into Armenian Apostolic (known also as Orthodox or at times Gregorian) belonging to the Armenian Apostolic Church and Armenian Catholic communities belonging to the Armenian Catholic Church. There are also some Egyptian Armenians who are members of Armenian Evangelical churches.

There are five main Armenian churches in Egypt, two in Alexandria and three in Cairo.

Armenian Orthodox community comprise the majority of Armenian Egyptians. The Armenian Apostolic churches include:

- Paul and Peter Armenian Apostolic Church (Alexandria)

- St. Gregory the Illuminator Armenian Apostolic Church (Sourp Krikor Lousavoritch Armenian Apostolic Church)(in Cairo).

The Prelacy of the Armenian Church in Egypt, which is under the jurisdiction of See of Holy Echmiadzin, is the primary guardian of community assets such as endowments, real estate in the form of agricultural land and other property bequeathed by generations of philanthropists.

The Armenian Catholic community has two churches:

- Armenian Catholic Patriarchate and the Church of the Assumption (Cairo)

- Armenian Catholic Patriarchate (in Alexandria)

- St. Therese Armenian Catholic Church (Heliopolis, Cairo)

The Armenian Evangelical community in Egypt currently has one church:

- Armenian Evangelical Church of Alexandria (in Alexandria) [8]

List of famous Armenians in Egypt

From Abbasid Era in the 7th century to the Ottoman Era of early 19th century

Among the most prominent Armenians in Egypt between the Abbasid Era in the 7th century to the Ottoman Era of the early 19th century were:

- Vartan the Standard Bearer, or Wardan al-Rumi al-Armani, who saved the life of Amr Ibn al-‘As, the commander of the Arab army at the Siege of Alexandria in 641. From this Vartan Al-Rumi comes the name of a market in Fustat known as the Vartan Market.

- Ali Ibn Yahya Abu’l Hassan al-Armani – the governor of Egypt in 841 and 849, appointed by the Abbasid Caliph, the spiritual and political guide and leader of Muslims at Baghdad. The courage of Ali, "[who was] versed in the science of war," is praised by the mediaeval Islamic historian Ibn Taghribirdi.

- Ahmed Ibn Tulun - the new prefect who in 876 was commissioned by Ibn Khatib Al-Ferghani to construct his mosque in his garrison town Al-Qata’i.

- Ibn Khatib Al-Ferghani - the master builder of Armenian ancestry who rebuilt the Nilometer on the southern tip of Rawda Island to measure the rise of the water level at the annual inundation of the Nile, a critical factor for the prosperity of Egypt.

- Badr al-Jamali - a manumitted slave of Armenian descent was called by Caliph al-Muntasir in 1073 to assist him during the Fatimid period when Egypt was weakened by inner strife and ravaged by drought, famine and epidemics. Badr's army, composed of mainly Armenian soldiers, is believed to have been formed after the fall of the Bagratuni capital, Ani (1066) when waves of Armenian refugees sought shelter in other countries. Badr al-Jamali was the first military man to become the Vezir (minister) of the Sword and the Pen, thus setting the trend for a century of mostly Armenian Vezirs with the same monopoly of civilian and military powers. At the height of their power, the Armenian Vezir could count on the personal loyalty of more than 20,000 men.

- Al-Afdal, the son of Badr al-Jamali constructed the Palace of Vezirate, or Dar al Wizarra, besides creating two public parks with exotic gardens, and a recreation area with a man-made lake called Birket al Arman, or Armenian Lake.

- Three brothers – all architects and masons skilled in cutting and dressing stones, who constructed the three monumental gates of Cairo: Bab al-Nasr and Bab al-Futuh in 1087 and Bab Zuwayla in 1092. The gates with their flanking towers still stand today. The ramparts and gates, which have a certain similarity to the fortifications of the Bagratuni Capital Ani, are regarded as masterpieces of military architecture by international standards.

- Bahram al-Armani – who, after restoring order and peace in the country at the request of Caliph al-Hafiz, was appointed by the latter as the Vezir in 1135.

- Baha al-Din Karakush - a eunuch and a Mamluk of the Kurdish general Shirkuh who in 1176 constructed a fortress, the Citadel, on the southeastern ridge of the Muqattam Hills and enclosed the new and old capitals, Cairo and Fustat, within a wall protected by the Citadel. Until the middle of the 19th century, the Citadel built by Karakush served as the seat of government fulfilling dual military and political functions.

- Shagarat Al-Durr (or Tree of Pearls) - a female slave who dazzled everyone with her spectacular display of gold and precious stone ornaments. She was sent to Egypt by the Abbasid Caliph al-Musta’sim as a gift to Sultan Salih Nagm al-Din Ayyub and became his favorite wife during his aging years. This strong-willed former slave wielded absolute power over Egypt during the transition period to Mamluk rule. She is one of the rare women in Islamic history who have ascended the throne and made a difference in the political and cultural spheres.

- Sinan Pasha - the Ottoman Empire's chief architect of Armenian descent, who constructed the historic Mosque of Bulaq, as well as Cairo's grain market, and Bulaq's public bathroom (Hammam).

- Amir Suleyman Bey al-Armani - held the position of Governor of Munnifeya and Gharbiyya provinces in 1690 and was so wealthy that he had Mamluks at his service.

- Ali al-Armani and Ali Bey al-Armani Abul Azab - served as regional commanders.

- Mustafa Jabarti - a Mamluk of Armenian descent from Tbilisi was a deputy of the agha or chief of ojak, and amassed a great fortune. He bought properties in the Armenian populated al-Zuwayla quarter and made donations to Armenians through his sister. He also built a hospice on the top floor of the quarter's St. Sarkis Church, to shelter Armenian immigrants, pilgrims and migrant workers, in need of temporary lodgings.

- Muhammad Kehia al-Armani – an incorruptible leader who in 1798 was sent to negotiate with Napoleon Bonaparte in Alexandria to spare the population of Cairo. Napoleon was so impressed by the conciliatory tone, the political astuteness, and the diplomatic skill of the Mamluk of Armenian descent that he later appointed him the Head of Cairo's Political Affairs Administration.

- Rustam (or Petros) - a native of Karabakh was brought to Egypt as a slave soldier. He accompanied Napoleon to France as his bodyguard, fought with the French army at the famous battle of Austerlitz, and then took part in the conquest of Spain.

- Apraham Karakehia - an eminent money changer was asked for financial help by Mohammed Ali. The Armenian money changer supported Muhammad Ali's projects and plans and was afterwards appointed the financial representative of the Albanian General. Karakehia would become Egypt's money changer, with the honorary title of Misser Sarrafi. That position and title would belong to the Karakehia family for generations to come.

- Mahdesi Yeghiazar Amira Bedrossian – another money changer from Agin who was named the Wali's, or Governor's, tax collector and special counselor. The Armenian money lender not only regulated the financial services and the taxation system but also initiated safeguards against illegal land seizures. At “various times, Armenian money lenders held the sole rights of exploiting the Cairo bathhouses, the salt mines of Matariya and the fish market of Damietta.” The influence of the Armenian money lenders increased even more during the 1830s, when due to the Russo-Turkish war and open persecution of Armenians, many merchants and financiers settles in Egypt and even succeeded in launching Egypt's first bank, which operated from 1837 to 1841.

- Yuhanna al-Armani - artist and Coptic icon painter who lived and worked in Cairo

Contributors to the modern Egypt

Armenians have historically contributed prominently to the Egyptian public life, be it in politics, economics, business and academic circles as well as in all facets of the arts.

Suffice to mention that Nubar Pasha, a prominent politician became the First Prime Minister of Egypt. Alexander Saroukhan is considered one of the prominent caricaturists who set the standards for the art of caricature in the Arab World.

According to media, modern sculptor Armen Agop is among the artists from Egypt that are changing perspectives on contemporary art from North Africa.[9]

Diaspora

Because of a rise of nationalism and pan-Arabism joined with confiscation of civil rights and economic freedoms, many Egyptians of Armenian descent decided in the late 1950s and during the 1960s to leave the country in many thousands to Europe and the Americas (United States, Canada, Latin America) and Australia. This greatly reduced the number of the Egyptian Armenian community in Egypt.

However the migrating Egyptian Armenians remained attached to their homeland Egypt and kept the Egyptian Armenian traditions and established their own associations in the new diaspora away from their country Egypt. They also actively contributed to the institutions still working in Egypt (churches, schools, clubs, cultural activities etc.). We can mention for example the Association of Armenians from Egypt in Montreal, Canada and many others in the United States.

See also

- Armenian diaspora

- Embassy of Armenia in Egypt

- List of Egyptian Armenians

- Kalousdian Armenian School

- Yacoubian Building

References

- Ayman Zohry, "Armenians in Egypt", International Union for the Scientific Study of Population: XXV International Population Conference, year 2005.

- G. Hovannisian, Richard (2004). The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times: Foreign dominion to statehood : the fifteenth century to the twentieth century. p. 423. ISBN 9781403964229.

- Payaslian, Simon (2007-12-26). The History of Armenia: From the Origins to the Present. p. 80. ISBN 9781403974679.

- M. Kurkjian, Vahan (1958). History of Armenia. Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. p. 246.

- Paul Adalian, Rouben (2010). Historical Dictionary of Armenia. Scarecrow Press. p. 226. ISBN 9780810874503.

- Armenian Cinema 100, by Artsvi Bakhchinyan, Yerevan, 2012, pp. 111-112

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1974). "The Ebb and Flow of the Armenian Minority in the Arab Middle East". Middle East Journal. 28 (1): 19–32. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4325183.

- Hovyan, Vahram (2011). ARMENIAN EVANGELICAL COMMUNITY IN EGYPT. Noravank Foundation. p. 1.

- "5 Egyptian artists working with innovative practices (by C. A. Xuan Mai Ardia) | •• REVOLUTION ART ••". •• REVOLUTION ART •• (in Italian). 2015-02-07. Retrieved 2018-03-17.