Albanians in Egypt

The Albanian community in Egypt started by Ottoman rulers and military personnel appointed in the Egyptian province. A substantial community would grow up later by soldiers and mercenaries who settled in the second half of the 18th century and made a name for themselves in the Ottoman struggle to expel French troops in 1798–1801. Muhammad Ali (1769–1849) who was of Albanian descent, was the ruler who had founded the New Kingdom of Egypt which lasted there until 1952. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many other Albanians settled into Egypt for economical and political reasons. With the fedayeen, Muslim Brotherhood, and the culminating Egyptian Revolution of 1952 the Albanian community in Egypt totally diminished and they settled in Western countries.

Shqiptarët e Misirit | |

|---|---|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 18,000[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Albanian, Egyptian Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Bektashi Order, Albanian Orthodox, less Sunni Islam, few Roman Catholics | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Albanians | |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

|

Native Albania · Kosovo Croatia · Greece · Italy · Montenegro · North Macedonia · Serbia Diaspora Australia · Bulgaria · Denmark · Egypt · Finland · Germany · Norway · Romania · South America · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom · United States |

| Culture |

| Architecture · Art · Cuisine · Dance · Dress · Literature · Music · Mythology · Politics · Religion · Symbols · Traditions · Fis |

| Religion |

| Christianity (Catholicism · Orthodoxy · Protestantism) · Islam (Sunnism · Bektashism) · Judaism |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Albanian Gheg (Arbanasi · Upper Reka dialect · Istrian) · Tosk (Arbëresh · Arvanitika · Calabria Arbëresh · Cham · Lab) |

| History of Albania |

Ottoman Era

Since 1517, Egypt became an Ottoman province. An Ottoman ruler would be appointed in Cairo. The title "beylerbey" refers to the regular governors specifically appointed to the post by the Ottoman sultan, while the title "kaymakam", when used in the context of Ottoman Egypt, refers to an acting governor who ruled over the province between the departure of the previous governor and the arrival of the next one. Several of these were of Albanian descent, as well as many within the military and bashiazouk units. Between the most known were Dukakinzade Mehmed Pasha,[2] Koca Sinan Pasha,[3] Abdurrahman Abdi Arnavut Pasha, and Mere Hüseyin Pasha.[3]

During and after the French campaign in Egypt and Syria, the Ottomans would deploy many Albanian pashas, beys, military units, as well as auxiliary personnel. Some of them were Tahir Pasha Pojani with his brothers Hasan Pasha, Dalip, Isuf, and Abdul Bey, Omer Pasha Vrioni, Muharrem Bey Vrioni, Rustem Aga Shkodrani and so on.[4] Sarechesme Halil Agha, commanding the Kavala Volunteer Contingent, would bring along his cousin, Muhammad (Mehmed) Ali, a young second rank commander.

Muhammad Ali Era

Muhammad Ali was an Albanian commander in the Ottoman army that was sent to drive Napoleon's forces out of Egypt, but upon the French withdrawal, seized power himself and forced the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II to recognize him as Wāli, or Governor of Egypt in 1805. His father, Ibrahim Agha, was from Korca, Albania, who had moved to Kavala. Demonstrating his grander ambitions, he took the title of Khedive; however, this was not sanctioned by the Sublime Porte.

Muhammad Ali transformed Egypt into a regional power which he saw as the natural successor to the decaying Ottoman Empire. He constructed a military state with around four percent of the populace serving the army to raise Egypt to a powerful positioning in the Ottoman Empire in a way showing various similarities to the Soviet strategies (without communism) conducted in the 20th century.[5] Muhammad Ali summed up his vision for Egypt in this way:

I am well aware that the [Ottoman] Empire is heading by the day toward destruction. ... On her ruins I will build a vast kingdom ... up to the Euphrates and the Tigris.

— Georges Douin, ed., Une Mission militaire française auprès de Mohamed Aly, correspondance des Généraux Belliard et Boyer (Cairo: Société Royale de Géographie d'Égypte, 1923), p.50

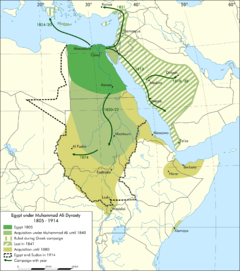

At the height of his power, Muhammad Ali and his son Ibrahim Pasha's military strength did indeed threaten the very existence of the Ottoman Empire as he sought to supplant the Osman Dynasty with his own. Ultimately, the intervention of the Great Powers prevented Egyptian forces from marching on Constantinople, and henceforth, his dynasty's rule would be limited to Africa, and Sinai. Muhammad Ali had conquered Sudan in the first half of his reign and Egyptian control would be consolidated and expanded under his successors, most notably Ibrahim Pasha's son Isma'il I.

Khedivate and British occupation

Though Muhammad Ali and his descendants used the title of Khedive (Viceroy) in preference to the lesser Wāli, this was not recognized by the Porte until 1867 when Sultan Abdul-Aziz officially sanctioned its use by Isma'il Pasha and his successors. In contrast to his grandfather's policy of war against the Porte, Isma'il sought to strengthen the position of Egypt and Sudan and his dynasty using less confrontational means, and through a mixture of flattery and bribery, Isma'il secured official Ottoman recognition of Egypt and Sudan's virtual independence. This freedom was severely undermined in 1879 when the Sultan colluded with the Great Powers to depose Isma'il in favor of his son Tewfik. Three years later, Egypt and Sudan's freedom became little more than symbolic when the United Kingdom invaded and occupied the country, ostensibly to support Khedive Tewfik against his opponents in Ahmed Orabi's nationalist government. While the Khedive would continue to rule over Egypt and Sudan in name, in reality, ultimate power resided with the British High Commissioner.

In defiance of the Egyptians, the British proclaimed Sudan to be an Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, a territory under joint British and Egyptian rule rather than an integral part of Egypt. This was continually rejected by Egyptians, both in government and in the public at large, who insisted on the "unity of the Nile Valley", and would remain an issue of controversy and enmity between Egypt and Britain until Sudan's independence in 1956.

Sultanate and Kingdom

In 1914, Khedive Abbas II sided with the Ottoman Empire which had joined the Central Powers in the World War I, and was promptly deposed by the British in favor of his uncle Hussein Kamel. The legal fiction of Ottoman sovereignty over Egypt and Sudan, which had for all intents and purposes ended in 1805, was officially terminated, Hussein Kamel was declared Sultan of Egypt and Sudan, and the country became a British Protectorate. With nationalist sentiment rising, as evidenced by the revolution of 1919, Britain formally recognized Egyptian independence in 1922, and Hussein Kamel's successor, Sultan Fuad I, substituted the title of King for Sultan. However, British occupation and interference in Egyptian and Sudanese affairs persisted. Of particular concern to Egypt was Britain's continual efforts to divest Egypt of all control in Sudan. To both the King and the nationalist movement, this was intolerable, and the Egyptian Government made a point of stressing that Fuad and his son King Farouk I were "King of Egypt and Sudan".

Dissolution

The reign of Farouk was characterized by ever increasing nationalist discontent over the British occupation, royal corruption and incompetence, and the disastrous 1948 Arab–Israeli War. All these factors served to terminally undermine Farouk's position and paved the way for the revolution of 1952. Farouk was forced to abdicate in favor of his infant son Ahmed-Fuad who became King Fuad II, while administration of the country passed to the Free Officers Movement under Muhammad Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser. The infant king's reign lasted less than a year and on June 18, 1953, the revolutionaries abolished the monarchy and declared Egypt a republic, ending a century and a half of the Muhammad Ali Dynasty's rule. Emerging victorious from a war-triangle (Ottomans, Mamluks, and his loyal troops), Mehmed Ali made good use of Albanian irregulars services as mercenaries and troops to bolster his reign. Albanian mercenaries, or Arnauts, presented the backbone of Ali's army and were known as elite and undisciplined soldiers of the Ottoman Empire armies.[6][7][8][9] With the rise of Muhammad Ali in power, many of them would settle in Egypt and serve there. By 1815, the number of Albanian military was over 7000.[4] Albanian troops partook in the war against the Wahhabi movement in Arabia (1811–18) and in the conquest of the Sudan (1820–24).[10][11] The number of Albanian troops would diminish in 1823, when Ibrahim Pasha, Ali's son, would join the Ottoman armies in the Greek War of Independence along with circa 17,000 men, many of them Albanians.[12] Ali's dynasty would continue to rule Egypt until 1952.

Albanian National Awakening and early 20th century

Albanian immigration to Egypt continued throughout the 19th century, and indeed into the first three decades of the 20th century. By that time Egypt experienced a massive economic development and prosperity, French and British investments (i.e. the Suez Canal), modernization, and opportunity for entrepreneurship. The economical prosperity attracted many emigrants from the Albanian lands, mainly from Korçë and Kolonjë regions. With some exceptions, most of the figures were educated members of the Orthodox community from south Albania who stationed in the vicinity of the Greek communities. Some of them published articles in the Greek community newspapers as well, frequently polemizing regarding Albanian identity.[13] The Albanian community in Egypt, with their patriotic societies and publishing activities, played an important role in the Albanian national awakening at the end of the 19th century.[14] The first Albanian society of Egypt was founded in 1875. It was named "Vëllazëria e Parë" (First Brotherhood) and was led by Thimi Mitko.[4]

Nationalist figures and writers such as Thimi Mitko, Spiro Dine, Filip Shiroka, Jani Vruho, Nikolla Naço, Anastas Avramidhi, Thoma Kreini, Thoma Avrami, Thanas Tashko, Stefan Zurani, Andon Zako Çajupi, Mihal Zallari, Milo Duçi, Loni Logori, Fan Noli, Aleksandër Xhuvani, Gaqo Adhamidhi and many others were all active in Egypt at some point in their careers. Some of them used it as temporary solution before moving to US or elsewhere, while some other settled permanently. Spiro Dine founded in 1881 the local branch of Society for the Publication of Albanian Writings in Shibin Al Kawm, a precursor and lobbyist for the Albanian education which started with the Albanian School of Korçë.[15] Many newspapers and collections would come out, including the successful Shkopi ("The stick"), Rrufeja ("The lightning"), Belietta Sskiypetare ("The Albanian Bee") and so on.[6] Many others would come out for a shorter time: Milo Duçi would publish the magazines Toska (The Tosk) during 1901–02, Besa-Besë (Pledge for a pledge) during 1904-05 together with Thoma Avrami, Besa (Besa) of 1905 which lasted for 6 issues and was printed by Al-Tawfik in Cairo,[16] and newspapers Shqipëria (Albania) from October 1906 to February 1907, a daily of Cairo with the last two issues coming out in Maghagha,[16] and the weekly Bisedimet (The discussions) of 1925–26 with 60 issues in total, which would be the last Albanian-language newspaper in Egypt.[4] Aleksander Xhuvani published the newspaper Shkreptima (The lightning) in 1912 in Cairo. In 1922, Duçi established also the publishing company Shtëpia botonjëse shqiptare/Société Albanaise d'édition (Albanian Publishing House).[17] Prominent Albanian organizations were: "Vëllazëria Shqiptare" (Albanian Fraternity) founded on 1 My 1894 in Beni-Suef, and "Bashkimi" (The union) which was found everywhere in Albanian populated areas and diaspora. It was an Albanian high official in Egypt, who sponsored the Giuseppe Verdi's opera Aida in Khedivial Opera House in 1871.[18]

In 1907, with the initiative of Mihal Turtulli, Jani Vruho, and Thanas Tashko, the Albanian community send a promemorium to the Second Hague Conference for Peace, demanding support for the civic rights of the Albanian population under the oppression of Abdul Hamid II. Thanas Tashko would represent the community in the Congress of Manastir of 1908,[4] while Loni Logori in the Congress of Elbasan of 1909. Another prominent Albanian, Fan Noli, would settle shortly in Egypt. Vruho and Tashko convinced him to move to US, and supported him financially. Another memorandum was signed with the initiative of Andon Zako and was sent to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. In 1924, a regrouping of the Albanian clubs and societies was done in Cairo, under a unique society named "Lidhja e Shqiptarve te Egjiptit" (The League of the Albanians of Egypt), with Jani Vruho as chairman.[4] More societies would follow; "Shoqerija Mireberse" (Benefactor Society) of Hipokrat Goda from Korçë established in 1926, and "Shoqeria e Miqeve" (Friends' Club) of Andon Zako in 1927. Thoma Kreini founded the "Tomorri" society, hoping to publish a newspaper with the same name but was unsuccessful.[4] An Albanian school operated during 1934–1939, initially supported by the "Shpresa" (Hope) society founded by Stathi Ikonomi, and later by the exiled King Zog I.[4] Evangjel Avramushi established in 1940 the first cinematographic studio in Egypt, named "AHRAM". The Albanian Bektashi community had its own tekke in Egypt,[6] the famed "Magauri tekke" on the outskirts of Cairo, which was headed by Baba Ahmet Sirri Glina of Përmet.[14] The tekke would be visited frequently by King Faruk. Prince Kamal el Dine Hussein, Princess Zeynepe, daughter of Isma'il Pasha, Princess Myzejen Zogolli, sister of King Zog I were some of the notables who were buried there.[4]

Discrimination

Immediately afterwards - with the seizure of power by Gamel Abdel Nasser and the subsequent nationalist Arabization policy in Egypt. Many Albanians left Egypt for Albania and the United States. Many Albanian families who decided to stay in Egypt were partly assimilated and partly killed from the Army of Gamel Abdel Nasser.

A few Albanians kept coming to Egypt throughout World War II and afterwards, most of them doing so to escape the Communist regime in Albania established on November 1944. Names would include Baba Rexheb, a Bektashi monk, former minister Mirash Ivanaj, Branko Merxhani, and even the former King Ahmet Zogu with his family. After King Zog and the Albanian royal family were forced out of Albania during the war, they took up residence in Egypt from 1946 to 1955 and were received by King Farouk who reigned during 1936–1952, himself a descendant of Mehmed Ali Pasha. The presence of this Albanian community lasted in Egypt until Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power. With the advent of Gamal Abdel Nasser and the Arab nationalization of Egypt, not only the royal family but also the entire Albanian community of around 4,000 families became the targets of hostility. They were forced to leave the country, thus closing the Albanian chapter in Egypt. Most of the Bektashi community moved to U.S. or Canada. Baba Rexheb established the first Albanian-American Bektashi monastery in the Detroit suburb of Taylor.[19] With the rise in power of Anwar Sadat, the stance toward Albanians changed, but just a few from the exiled families returned to Egypt.[4] In recent times the number of people estimated to be of Albanian heritage in Egypt is 18,000.[1]

Famous Albanians of Egypt

In art

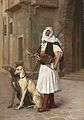

In 1856, the French painter Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) journeyed to Egypt. This visit was decisive for his development as an Orientalist painter and much of his subsequent work was devoted to orientalist paintings. The sizeable Albanian guards and the janissary troops settled on the banks of the Nile during the early rule of Mehmed Ali' dynasty, played a major role in Gérôme's paintings. He was fascinated by their swagger, their weapons and their costumes, particularly by the pleats of their typical white fustanellas.[20] The following is a selection of some of his paintings:

Egyptian Recruits Crossing the Desert, 1857.

Egyptian Recruits Crossing the Desert, 1857. Albanian guards playing dice, 1859.

Albanian guards playing dice, 1859.%2C_1861.jpg) Albanian Guard in Cairo, 1861.

Albanian Guard in Cairo, 1861. A Joke – An Albanian Blowing Smoke into his Dog's Nose, 1864.

A Joke – An Albanian Blowing Smoke into his Dog's Nose, 1864. Prayer in the Desert, 1864.

Prayer in the Desert, 1864. An Albanian on his donkey crossing the desert, unknown date.

An Albanian on his donkey crossing the desert, unknown date.%2C_1865.jpg) An Albanian with his Dog, 1865.

An Albanian with his Dog, 1865. An Albanian with Two Whippets, 1867.

An Albanian with Two Whippets, 1867. An Albanian Smoking, 1868.

An Albanian Smoking, 1868. Bashi-Bazouk Singing, 1868.

Bashi-Bazouk Singing, 1868. An Albanian Bashi-Bazouk, 1896.

An Albanian Bashi-Bazouk, 1896. Bashi-Bazouk Chieftain, 1881

Bashi-Bazouk Chieftain, 1881

See also

- Albanians in Turkey

- Ottoman Albania

- Ashkali and Balkan Egyptians – cultural and ethnic minority in Albania

- Sufism

References

Citations

- Saunders 2011, p. 98. "Egypt also lays claim to some 18,000 Albanians, supposedly lingering remnants of Mohammad Ali's army."

- Winter 2004, p. 35.

- Öztuna 1979, p. 51.

- Uran Asllani (2006-06-05), Shqiptarët e egjiptit dhe veprimtaria atdhetare e tyre [Albanians of Egypt and their patriotic activity] (in Albanian), Gazeta Metropol

- Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 217. ISBN 9781107507180.

- Norris 1993, pp. 209–210. "This was an age when Albanians and Bosnians were posted to garrisons within the Nile regions, and furthermore the bulk of the Albanian troops were uncultured, exceedingly unruly, and often hated. Yet the dynasty that Muhammad ‘Alī established, the affection it had for Albanians and received from them, and the haven it afforded to them as exiles from Ottoman control, victimisation by Greek neighbours, or the sheer misery of Balkan poverty, meant that in time Alexandria, Cairo, Beni Suef and other Egyptian towns would harbour Albanians who organised associations, published newspapers and above all wrote works in verse and prose that include significant masterpieces of modern Albanian literature. Within al-Azhar and the two Baktāshi tekkes in Cairo, Qaṣr al-’Aynī and Kajgusez Abdullah Megavriu, Albanians and Balkan contemporaries were to find inspiration for a mystical quest, and artistic and literary stimulus, that sent ripples, as on a pond, throughout Albanian and Egyptian circles in Cairo and distantly and remotely in towns of Albania, Kosovo and Macedonia. Some of the outstanding literary figures of modern Albanian literature — for example, Thimi Mitko (d. 1890), the author of collections of Albanian folksongs, folk-tales and sayings, in his The Albanian Bee (Bleta Shqypëtare), Spiro Dine (d. 1922) in his Waves of the Sea (Valët e detit) and Andon Zako Çajupi (1866-1930) in his Baba Tomorri (Cairo, 1902) and his Skanderbeg drama — although they lived in Egypt for much of their lives, were essentially nationalists and not much influenced by the Islamic way of life that they saw around them. If anything, the rural arid peasant life in Egypt acted as a spur to their absorption in popular traditions which, in their view, enshrined the soul of their people. The Albanians in Egypt were, without a doubt, influenced by the Egyptian theatre — but specifically by those elements not overtly infused with Islamic sentiments. Later writers became prominent figures among the Albanian community in Cairo. Milo Duçi (Duqi) (d. 1933) did so because of his office as president of the national ‘Brethren’ league (Villazëria/Ikhwa), and by his Albanian newspapers (al-‘Ahd, 1900, known in Egypt as al-Aḥādīth, 1925). He also wrote plays, especially ‘The Saying’ (E Thëna, 1922) and ‘The Bey's Son’ (1923), and a novel Midis dy grash (Between two women, 1923). More recently still, it has been secular and Arab nationalist causes such as Palestine and Algeria that have inspired Albanian Egyptian writers."

- Fraser 2014, p. 92.

- Carstens 2014, p. 753.

- University of Wisconsin 2002, p. 130.

- Fahmy 2002, p. 40, 89.

- Fahmy 2012, p. 30.

- Cummins 2009, p. 60.

- Skoulidas 2013. para. 15, 22, 25, 28.

- Elsie 2010, pp. 125–126.

- Elsie 2010, p. 111.

- Blumi 2012, pp. 131–132.

- Blumi 2011, p. 205.

- Trix 2009, p. 107.

- Curtis 2010, p. 83.

- Elsie, Robert. "Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904)". albanianart.net.

Sources

- Blumi, Isa (2011). Reinstating the Ottomans, Alternative Balkan Modernities: 1800–1912. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 9780230119086.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blumi, Isa (2012). Foundations of Modernity: Human Agency and the Imperial State. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415884648.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carstens, Patrick Richard (2014). The Encyclopædia of Egypt during the Reign of the Mehemet Ali Dynasty 1798-1952: The People, Places and Events that Shaped Nineteenth Century Egypt and its Sphere of Influence. Victoria: FriesenPress. ISBN 9781460248980.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cummins, Joseph (2009). The War Chronicles: From Flintlocks to Machine Guns. Beverly: Fair Winds. ISBN 9781616734046.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curtis, Edward E. (2010). Encyclopedia of Muslim-American History. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438130408.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810873803.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fahmy, Khaled (2002). All the Pasha's men: Mehmed Ali, his army and the making of modern Egypt. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 9789774246968.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fahmy, Khaled (2012). Mehmed Ali: From Ottoman Governor to Ruler of Egypt. New York: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781780742113.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fraser, Kathleen W. (2014). Before They Were Belly Dancers: European Accounts of Female Entertainers in Egypt, 1760-1870. Jefferson: McFarland. ISBN 9780786494330.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norris, Harry Thirlwall (1993). Islam in the Balkans: religion and society between Europe and the Arab world. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 249. ISBN 9780872499775.

Albanians Arnaout Syria.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Öztuna, Yılmaz (1979). Başlangıcından zamanımıza kadar büyük Türkiye tarihi: Türkiye'nin siyasî, medenî, kültür, teşkilât ve san'at tarihi. Istanbul: Ötüken Yayınevi. ISBN 975-437-141-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saunders, Robert A. (2011). Ethnopolitics in Cyberspace: The Internet, Minority Nationalism, and the Web of Identity. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739141946.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skoulidas, Elias (2013). "The Albanian Greek-Orthodox Intellectuals: Aspects of their Discourse between Albanian and Greek National Narratives (late 19th - early 20th centuries)". Hronos. 7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Trix, Frances (2009). The Sufi Journey of Baba Rexheb. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9781934536544.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- University of Wisconsin (2002). "International Journal of Turkish Studies". International Journal of Turkish Studies. 8 (1/2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Winter, Michael (2004). Egyptian society under Ottoman rule, 1517-1798. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781134975136.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)