Armenians in Tbilisi

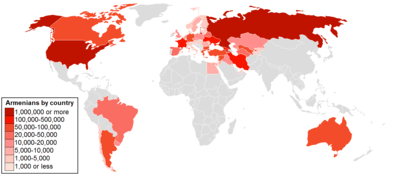

The Armenians have historically been one of the main ethnic groups in the city of Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. Armenians are the largest ethnic minority in Tbilisi at 4.8% of the population. Armenians migrated to the Georgian lands in the Middle Ages, during the Muslim rule of Armenia. They formed the single largest group of city's population in the 19th century. Official Georgian statistics of 2014 put the number of Armenians in Tbilisi 53,409 people.[10]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 55,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tbilisi | |

| Languages | |

| Armenian | |

| Religion | |

| Armenian Apostolic Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Armenians in Georgia |

| Year | TOTAL | Armenians | % | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1801-3[1][2] | 20,000 | 14,860 | 74.3% | ||||||||||||||

| 1864/65 winter[3] | 60,085 | 28,404 | 47.3% | ||||||||||||||

| 1864/65 summer[3] | 71,051 | 31,180 | 43.9% | ||||||||||||||

| 1876[4] | 104,024 | 37,610 | 36.1% | ||||||||||||||

| 1897[5] | 159,590 | 41,151 | 36.4% | ||||||||||||||

| 1916[6] | 346,766 | 149,294 | 43% | ||||||||||||||

| 1926[7] | 294,044 | 100,148 | 34.1% | ||||||||||||||

| 1939[7] | 519,220 | 137,331 | 26.4% | ||||||||||||||

| 1959[7] | 694,664 | 149,258 | 21.5% | ||||||||||||||

| 1970[7] | 889,020 | 150,205 | 16.9% | ||||||||||||||

| 1979[7] | 1,052,734 | 152,767 | 14.5% | ||||||||||||||

| 2002 [8] | 1,081,679 | 82,586 | 7.6% | ||||||||||||||

| 2014[9] | 1,108,717 | 53,409 | 4.8% | ||||||||||||||

Tbilisi or Tiflis (as most Armenians call it) was the center of cultural life of Armenians in the Russian Empire from early 19th century to early 20th century.

History

The Armenian history and contribution to the capital city of Tbilisi (known as Tiflis in Armenian, Russian, Persian, Azerbaijani and Turkish) is significant. After the Russian conquest of the area, Armenians fleeing persecution in the Ottoman Empire and Persia caused a jump in the Armenian population until it reached about 40% of the city total. Many of the mayors and business class were Armenian, and much of the old city was built by Armenians. Until recently the neighborhoods of Havlabar and the area across the river were very heavily Armenian, but that has changed a great deal in the last two decades.

An Armenian community has been known to have existed in Tbilisi since at least the 7th century, however a large Armenian community was not formed until the Late Middle Ages.[11] By the late Middle Ages, there were some 24 Armenian churches and monasteries in and around the city.[11] According to Tournefort, Armenians constituted three-quarters of the population of Tiflis in the 18th century, and owned 24 churches.[12]

Under the Russian Empire, the city of Tiflis became the center of Russian rule for the whole viceroyalty of Caucasia. During the 19th century, Tiflis became the center of the Eastern Armenian cultural revival and an Armenian cultural hub second only to Constantinople.[11]

Until recently, the neighborhoods of Avlabari (Havlabar) and the area across the river were very heavily Armenian. The older Armenian neighborhood of Tbilisi, on both sides of the river between Freedom Square and Havlabar carry Armenian names, including Tumanyan, Abovian, Akopian, Alikhanian, Sundukian, Yerevan, Ararat and Sevan.

The Diocese Church (the Saint Gevorg Church) in Tbilisi where the Armenian primate of Tbilisi sits is very close to the city fortress. In front of the church is the tomb of the 18th-century Armenian–Georgian bard, Sayat-Nova. In Havlabar, the other Armenian Church of Echmiadzin is undergoing renovation and reconstruction. The Armenian Pantheon of Tbilisi has the tombs of many famous Armenians including writers Hovhannes Tumanyan and Raffi.

Armenian sites

Churches

According to Tournefort, Armenians constituted three-quarters of the population of Tiflis in the 18th century, and owned 24 churches.[12] Ten of the churches were destroyed in the 1930s, and as of 1979, fourteen were still standing.[13]

There are still two working Armenian Churches in the city, and an Armenian Theatre. The Armenian Pantheon, where prominent Armenians are buried has the tombs of some of Armenian's favorite personalities ever, including Raffi and Hovhannes Tumanyan. The adjacent Armenian cemetery was taken over by the Georgian Church and their new national cathedral was built upon it. The remaining space in between the Pantheon and the new Georgian cathedral is now the construction site of what appears to be a Georgian Seminary. Again, the Armenian tombs here are being ignored, and human bones are being moved around like dirt.

A number of Armenian churches were confiscated by the Soviet state and then passed to the Georgian Church in the post-Soviet era. According to the United States State Department: "The Roman Catholic and Armenian Apostolic Churches have been unable to secure the return of churches and other facilities closed during the Soviet period, many of which later were given to the Georgian Orthodox Church by the State. The prominent Armenian church in Tbilisi, Norashen, remained closed, as did four other smaller Armenian churches in Tbilisi and one in Akhaltsikhe. In addition, the Roman Catholic and Armenian Apostolic Churches, as with Protestant denominations, have had difficulty obtaining permission to construct new churches due to pressure from the GOC." [14]

Petros Adamian Tbilisi State Armenian Drama Theatre

Petros Adamian Tbilisi State Armenian Drama Theatre was established in 1858 by the Armenian theatre figure George Chmshkian. The first staging was "Adji Suleyman" performance. From 1922 through 1936 before building of the new current theatre building the theatres name was "Artistic theatre". In 1936 was built a new theatre building which was named Stepan Shahumian Armenian Theatre, after Bolshevik Stepan Shahumian. The first performance was Mkrtich (Nikita) Djanan's performance "Shahname". Here worked Petros Adamian, Siranoush (Merobe Kantarjian), Vahram Papazian, Hovhannes Abelian, Olga Maysourian, Isaac Alikhanian, Mariam Mojorian, Artem and Maria Beroians, Artem Lusinian, Babken Nersesian, Darius Amirbekian, Ashot Kadjvorian, Emma Stepanian, Armenian directors: Arshak Bourdjalian, Leon Kalantar, Stepan Kapanakian, Alexander Abarian, Ferdinand Bzhikian, Hayk Umikian, Mickael Grigorian, Ivan Karapetian, Roman Chaltikian, Roman Matiashvili, Robert Yegian. Music for theatres often was written by Aram Khachaturian, Armen Tigranian, Alexander Spendiarian, and others.

Nowadays Peter Adamian Tbilisi State Armenian Drama Theatre is the main spiritual and public center of Georgian-Armenian community.[15]

Nersisyan School

Freedom Square

Once formally known as Paskevich Yerevanski Square, then Lenin Square, it was commonly called Yerevan Square. Ivan Paskevich was a Russian general and was called Paskevich of Yerevan (Yerevanski) in honor of his taking of Yerevan for the Russian Empire. Abutting the north side of Freedom Square is a small open space with a fountain. Buried between the bust of Pushkin and the fountain is the Bolshevik revolutionary Kamo (Simon Ter-Petrossian). His grave has been paved over and is unmarked.

Armenian Street Names

The heavily Armenian old neighborhoods of Tbilisi still have many Armenian street names, though some have been changed over time. Leselidze Street was once called Armenian Bazaar Street.

Vera cemetery

Vera cemetery was used by local Armenians before the Soviet takeover. Now it is used by Georgians.

Notable Armenians from Tbilisi

Pre-Revolution

- Sayat-Nova (1712–1795), poet, musician and ashik who had compositions in a number of languages

- Vasili Bebutov (1791–1858), Russian-Armenian general, a descendant of a Georgian-Armenian noble house of Bebutashvili/Bebutov

- Stepanos Nazarian (1812–1879), publisher, enlightener, historian of literature and orientalist

- Gabriel Sundukian (1825–1912), outstanding playwright, the founder of modern Armenian drama

- Mikhail Loris-Melikov (1826–1888), Russian-Armenian statesman, General of the Cavalry, and Adjutant General of H. I. M. Retinue

- Nar-Dos (1867–1933), writer

- Mariam Vardanian (1864–1941), political activist and revolutionary in the Russian Empire. She was one of the founders of the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party

- Hovhannes Tumanyan (1869–1923), the greatest Armenian poet and writer

- Nikol Aghbalian (1875–1947), public figure and historian of literature, 1919-1920 he was the Minister of Education and Culture of the First Republic of Armenia

- Alexander Khatisyan (1874–1945), politician and a journalist, mayor of Tbilisi (1910-1917) and Prime Minister of the First Republic of Armenia (1919-1920)

- Christophor Araratov (1876–1937), major-general

Soviet era

- Stepan Shahumyan (1878–1918), Bolshevik politician and revolutionary active throughout the Caucasus

- Tovmas Nazarbekian (1885–1931), general

- Sargis Barkhudaryan (1887–1973), Armenian composer, pianist and educator

- Rouben Mamoulian (1897–1987), Armenian-American film and theatre director.

- Yervand Kochar (1899–1979), prominent Armenian sculptor and artist

- Aram Khachaturian (1903–1978), prominent Soviet Armenian composer

- Alexander Melik-Pashayev (1905–1964), conductor

- Dmitriy Nalbandyan (1906–1993), painter

- Suren Yeremyan (1908–1992), historian and cartographer

- Rafayel Israyelian (1908–1973), Armenian architect and designer

- Artem Alikhanian (1908–1975), Soviet Armenian physicist, one of the founders and first director of the Yerevan Physics Institute

- Viktor Hambardzumyan (1908–1996), famous Soviet Armenian scientist, and one of the founders of theoretical astrophysics

- Edward Keonjian (1909–1999), prominent engineer, an early leader in the field of low-power electronics, the father of microelectronics

- Genrikh Kasparyan (1910–1995), considered to have been one of the greatest composers of chess endgame studies

- Konstantine Hovhannisyan (born 1911), professor, architect and archaeologist

- Sebastian Shaumyan (1916–2007), Soviet-Armenian and American theoretician of linguistics and an outspoken adherent of structuralist analysis

- Karen Ter-Martirosian (1922–2005), Russian theoretical physics scientist

- Sergei Parajanov (1924-1990), film director and artist

- Rafael Chimishkyan (born 1929), former weightlifter and Olympic champion who competed for the Soviet Union

- Tigran Petrosian (1929-1984), Soviet-Armenian grandmaster, and World Chess Champion from 1963 to 1969

- Evgeny Abramyan (born 1930), Soviet/Armenian physicist, Professor, Doctor of Engineering Sciences, Winner of USSR State Prize, one of the founders of several research directions in the Soviet and Russian nuclear technology

- Abel Aganbegyan (born 1932), leading Soviet and Russian economist

- Samvel Gasparov (born 1938), Soviet/Russian film director and short story writer

- Arkady Ter-Tadevosyan (Komandos) (born 1939), military leader of the Armenian forces during the Nagorno-Karabakh War

- Leonid Azkaldian (1942–1992), physicist, hero of the Nagorno-Karabakh War

- Gayane Khachaturian (1942–2009), painter and graphic artist

Post-Soviet

- Sergei Movsesian (born 1978), chess Grandmaster [16]

- Anna Kasyan (born 1981), French-based opera singer[17]

Sergey Viktorovich Lavrov (Russian: Серге́й Ви́кторович Лавро́в, pronounced [sʲɪrˈgʲej ˈvʲiktərəvʲɪtɕ ɫɐvˈrof]; born 21 March 1950) is a Russian diplomat and politician. In office since 2004, he is the Foreign Minister of Russia.[1] Previously, he was the Russian Representative to the UN, serving from 1994 to 2004.

See also

- Armenians in Abkhazia

- Armenians in Samtskhe-Javakheti

- Armenians in Georgia

- Armenian National Council of Tiflis

References

- Ronald Grigor Suny (1994). The making of the Georgian nation. Indiana University Press. pp. 116–. ISBN 978-0-253-20915-3. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "in 1803 it was considered up to 2700 houses in Tiflis from which more than 2500 belonged to Armenians. Thus, the capital made then quite the property of Armenians". (the guidebook across Caucasus of Russian geographer Vladikin, М.Владыкин, "Путеводитель и собеседник в путешествии по Кавказу", 1885 год, с.300.

- (in Russian) Тифлис // Географическо-статистический словарь Российской империи.St. Petersburg, 1885, p. 133 (Note: this is a 'one-day census' of unknown scope and methodology).

- Ronald Grigor Suny (1994). The making of the Georgian nation. Indiana University Press. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-253-20915-3. Retrieved 29 December 2011. (one-day census of Tiflis)

- (in Russian) Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г.. Изд. Центр. стат. комитета МВД: Тифлисская губерния. — St. Petersburg, 1905, pp. 74—75.(Note: the census did not contain a question on ethnicity, which was deduced from data on mother tongue, social estate and occupation)

- Caucasian Calendar, 1916. pp. 206-209

- (in Russian) Ethno-Caucasus, население Кавказа, республика Грузия, население Грузии

- Ethnic groups by major administrative-territorial units

- Total population by regions and ethnicity census.ge

- ETHNIC GROUPS BY MAJOR ADMINISTRATIVE-TERRITORIAL UNITS Archived August 31, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Statistics Georgia

- Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-33228-4.

- Thierry, Jean-Michel (1989). Armenian Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 317. ISBN 0-8109-0625-2.

- Thierry, Jean-Michel (1989). Armenian Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 586. ISBN 0-8109-0625-2.

- U.S. Department of State, International Religious Freedom Report 2005

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-02-10. Retrieved 2019-05-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Телеведущая Тина Канделаки - гость Антона Комолова и Ольги Шелест (in Russian). Radio Mayak. Archived from the original on April 1, 2008. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

КАНДЕЛАКИ: Ну, практически, папа меня, видимо, сделал на балконе этого дома под бриз Куры. Но мои родители, вернее как, моя мама, она армянка, и она из достаточно состоятельной семьи, которая, по истории моей семьи, в свое время вместе с купцами Гергидовыми, вначале они владели полностью, потом мои родители…

- "Anna Kasyan". Styriarte. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2013.