Arambourgiania

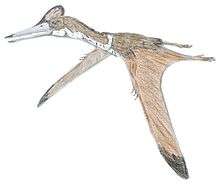

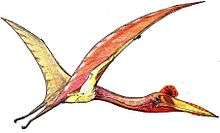

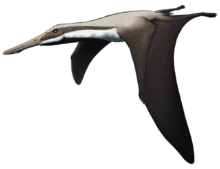

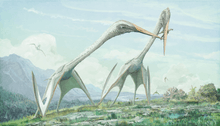

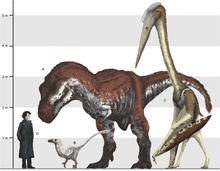

Arambourgiania is a pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Jordan and possibly the United States.[1] It was among the largest of the azhdarchids and one of the largest flying animals ever known.

| Arambourgiania | |

|---|---|

| Holotype fossil cast | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Family: | †Azhdarchidae |

| Genus: | †Arambourgiania Nessov vide Nessov & Yarkov, 1989 |

| Type species | |

| †Arambourgiania philadelphiae (Arambourg, 1959) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

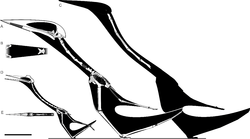

The holotype, VF 1, consists of a very elongated cervical vertebra, probably the fifth. Today the middle section is missing; the original find was about 62 centimetres (24 inches) long, but had been sawed into three parts. Most of the fossil consists of an internal infilling or mould; the thin bone walls are missing on most of the surface. The find had not presented the whole vertebra; a piece was absent from its posterior end as well. Frey and Martill estimated the total length to have been 78 centimetres (31 inches), using for comparison the relative position of the smallest shaft diameter of the fifth cervical vertebra of Quetzalcoatlus. From this again the total neck length was extrapolated at about 3 metres (9.8 feet). From the relatively slender vertebra the length dimension was then selected to be compared to that of Quetzalcoatlus, estimated at 66 centimetres (26 inches) long, resulting in a ratio of 1.18. Applying that ratio to the overall size, Frey and Martill in 1998 concluded that the wingspan of Arambourgiania had been 12–13 metres (39–43 feet), compared with the 10–11 metres (33–36 feet) of Quetzalcoatlus, and that Arambourgiania was thus the largest pterosaur then known. Later estimates have been more moderate, sometimes as low as seven metres.[2]

History of discovery

In the early 1940s, a railway worker during repairs on the Amman-Damascus railroad near Russeifa found a two foot long fossil bone. In 1943 this was acquired by the director of a nearby phosphate mine, Amin Kawar, who brought it to the attention of a British archeologist, Fielding, after the war. This generated some publicity — the bone was even shown to Abdullah I of Jordan — but more importantly, it made the scientific community aware of the find.

In 1953 the fossil was sent to Paris, where it was examined by Camille Arambourg of the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle. In 1954, he concluded the bone was the wing metacarpal of a giant pterosaur. In 1959, he named a new genus and species: Titanopteryx philadelphiae. The genus name meant "titan wing" in Greek; the specific name refers to the name of Amman in Antiquity: Philadelphia. Arambourg let a plaster cast be made and then sent the fossil back to the phosphate mine; this last aspect was later forgotten and the bone was assumed lost.

In 1975 Douglas A. Lawson, studying the related Quetzalcoatlus, concluded the bone was not a metacarpal but a cervical vertebra.

In the eighties, Russian paleontologist Lev Nesov was informed by an entomologist that the name Titanopteryx had already been given by Günther Enderlein to a fly from the Simulidae family in 1935. Therefore, in 1989 he renamed the genus into Arambourgiania, honouring Arambourg. However, the name "Titanopteryx" was informally kept in use in the West, partially because the new name was assumed by many to be a nomen dubium.

Early 1995, paleontologists David Martill and Eberhard Frey traveled to Jordan in an attempt to clarify matters. In a cupboard of the office of the Jordan Phosphate Mines Company they discovered some other pterosaur bones: a smaller vertebra and the proximal and distal extremities of a wing phalanx — but not the original find. However, after their departure to Europe engineer Rashdie Sadaqah of the mine investigated further and in 1996 established it had been bought from the company in 1969 by geologist Hani N. Khoury who had donated it in 1973 to the University of Jordan; it was still present in the collection of this institute and now could be restudied by Martill and Frey.

Frey and Martill rejected the suggestion that Arambourgiania was a nomen dubium or identical to Quetzalcoatlus and affirmed its validity in relation to "Titanopteryx".

Nesov in 1984 had placed the species within Azhdarchinae, part of the Pteranodontidae; the same year Kevin Padian placed it within Titanopterygidae. Both concepts have fallen into disuse now that such forms are commonly assigned to the Azhdarchidae.

In 2016, an Azhdarchid cervical vertebra was described from the Coon Creek Formation of McNairy County, Tennessee and referred to Arambourgiania philadelphiae. This find extends Arambourgiania's geographic range to North America.[1]

In 2018, topotype specimens were located in Bavarian State Collection for Palaeontology and Geology in Munich, Germany that were placed there in 1966 from Jordan and probably represent additional elements of the holotype individual, these include "fragments of two cervical vertebrae, a neural arch, a left femur, a ?radius, and a metacarpal IV" and other indeterminate fragments.[3]

Classification

Below is a cladogram showing the phylogenetic placement of Arambourgiania within Neoazhdarchia from Andres and Myers (2013).[4]

| Neoazhdarchia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Harrell, T. Lynn Jr.; Gibson, Michael A.; Langston, Wann Jr. (2016). "A cervical vertebra of Arambourgiania philadelphiae (Pterosauria, Azhdarchidae) from the Late Campanian micaceous facies of the Coon Creek Formation in McNairy County, Tennessee, USA" Bull. Alabama Mus. Nat. Hist. 33:94–103

- Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier; Bardet, N., Jouve, S., Iarochène, M., Bouya, B., and Amaghzaz, M. (2003). "A new azhdarchid pterosaur from the Late Cretaceous phosphates of Morocco". In: Buffetaut, E., and Mazin, J.-M. (eds.). Evolution and Palaeobiology of Pterosaurs. Geological Society of London, Special Publications, 217. p.87

- Martill, David M.; Moser, Markus (2018). "Topotype specimens probably attributable to the giant azhdarchid pterosaur Arambourgiania philadelphiae (Arambourg 1959)". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 455 (1): 159–169. doi:10.1144/SP455.6. ISSN 0305-8719.

- Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 103 (3–4): 1. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303.

References

- Arambourg, C. (1959). "Titanopteryx philadelphiae nov. gen., nov. sp. Ptérosaurien géant." Notes Mém. Moyen-Orient, 7: 229–234.

- Frey, E. & Martill, D.M. (1996). "A reappraisal of Arambourgiania (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea): One of the world's largest flying animals." N.Jb.Geol.Paläont.Abh., 199(2): 221-247.

- Martill, D.M., E. Frey, R.M. Sadaqah & H.N. Khoury (1998). "Discovery of the holotype of the giant pterosaur Titanopteryx philadelphiae Arambourg 1959, and the status of Arambourgiania and Quetzalcoatlus." Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paläontologie, Abh. 207(1): 57-76.

- Nessov, L.A., and Yarkov, A.A. (1989). "New Cretaceous-Paleogene birds of the USSR and some remarks on the origin and evolution of the class Aves". Trudy Zoologicheskogo Instituta AN SSSR, 197: 78–97. [In Russian]

- Steel, L., D.M. Martill., J. Kirk, A. Anders, R.F. Loveridge, E. Frey, and J.G. Martin (1997). "Arambourgiania philadelphiae: giant wings in small halls." The Geological Curator, 6(8): 305-313.