Gynandromorphism

A gynandromorph is an organism that contains both male and female characteristics. The term comes from the Greek γυνή (gynē), female, ἀνήρ (anēr), male, and μορφή (morphē), form, and is used mainly in the field of entomology. Notable gynandromorphic organisms are butterflies, moths and other insects, wherein both types of body part can be distinguished physically due to sexual dimorphism.

_gynandromorphe.jpg)

Occurrence in other genera

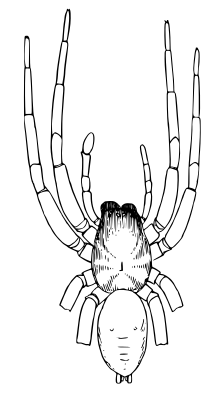

Gynandromorphism was first discovered by Bridges and Morgan in Drosophilla. It has been observed in numerous animal species, including crustaceans, such as lobsters and crabs, spiders and many species of bird.[1][2][3][4][5][6] A clear example in birds involves the zebra finch. These birds have lateralised brain structures in the face of a common steroid signal, providing strong evidence for a non-hormonal primary sex mechanism regulating brain differentiation.[7]

Pattern of distribution of male and female tissues in a single organism

A gynandromorph can have bilateral asymmetry—one side female and one side male.[8] Alternatively, the distribution of male and female tissue can be more haphazard. Bilateral gynandromorphy arises very early in development, typically when the organism has between 8 and 64 cells.[9] Later stages produce a more random pattern.

Normal female of Papilio androgeus

Normal female of Papilio androgeus Mosaic gynandromorph of Papilio androgeus

Mosaic gynandromorph of Papilio androgeus Normal male of Papilio androgeus

Normal male of Papilio androgeus

Causes

The cause of this phenomenon is typically, but not always, an event in mitosis during early development. While the organism contains only a few cells, one of the dividing cells does not split its sex chromosomes typically. This leads to one of the two cells having sex chromosomes that cause male development and the other cell having chromosomes that cause female development. For example, an XY cell undergoing mitosis duplicates its chromosomes, becoming XXYY. Usually this cell would divide into two XY cells, but in rare occasions the cell may divide into an X cell and an XYY cell. If this happens early in development, then a large portion of the cells are X and a large portion are XYY. Since X and XYY dictate different sexes, the organism has tissue that is female and tissue that is male.[10]

A developmental network theory of how gynandromorphs develop from a single cell based on internetwork links between parental allelic chromosomes is given in.[11] The major types of gynandromorphs, bilateral, polar and oblique are computationally modeled. Many other possible gynandromorph combinations are computationally modeled, including predicted morphologies yet to be discovered. The article relates gynandromorph developmental control networks to how species may form. The models are based on a computational model of bilateral symmetry.[12]

As a research tool

Gynandromorphs occasionally afford a powerful tool in genetic, developmental, and behavioral analyses. In Drosophila melanogaster, for instance, they provided evidence that male courtship behavior originates in the brain,[13] that males can distinguish conspecific females from males by the scent or some other characteristic of the posterior, dorsal, integument of females,[14][15] that the germ cells originate in the posterior-most region of the blastoderm,[16] and that somatic components of the gonads originate in the mesodermal region of the fourth and fifth abdominal segment.[17]

See also

References

- Chen, Xuqi; Agate, Robert J.; Itoh, Yuichiro; Arnold, Arthur P. (2005). "Sexually dimorphic expression of trkB, a Z-linked gene, in early posthatch zebra finch brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (21): 7730–5. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.7730C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408350102. PMC 1140405. PMID 15894627. Lay summary – Scientific American (March 25, 2003).

- Gouldian finch Erythrura gouldiae Gynandromorph Archived 2006-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Powderhill Banding Fall 2004 Archived 2006-12-31 at the Wayback Machine

- A Gender-bender Colored Cardinal, by Tim Wall, Discovery News, 31 May 2011

- "Half-cock chicken mystery solved". BBC News. 11 March 2010.

- Suzuki, Yuya; Kuramitsu, Kazumu; Yokoi, Tomoyuki (2019-06-14). "Morphology and sex-specific behavior of a gynandromorphic Myrmarachne formicaria (Araneae: Salticidae) spider". The Science of Nature. 106 (7): 34. doi:10.1007/s00114-019-1625-x. ISSN 1432-1904.

- Arnold, Arthur P. (2004). "Sex chromosomes and brain gender". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 5 (9): 701–8. doi:10.1038/nrn1494. PMID 15322528.

- Ian Sample, science correspondent (12 July 2011). "Half male, half female butterfly steals the show at Natural History Museum". London: The Guardian. Retrieved August 6, 2011.

- Malmquist, David (June 15, 2005). "Rare crab may hold genetic secrets". Virginia Institute of Marine Science.

- Adams, James K. "Gynandromorphs". Department of Natural Sciences, Dalton State College. Archived from the original on 2013-03-07. Retrieved 2005-06-29.

- Werner, Eric (2012). "A Developmental Network Theory of Gynandromorphs, Sexual Dimorphism and Species Formation". arXiv:1212.5439.

- Werner, Eric (2012). "The Origin, Evolution and Development of Bilateral Symmetry in Multicellular Organisms". arXiv:1207.3289.

- Hotta, Y, and Benzer, S. (1972). "Mapping of Behaviour in Drosophila mosaics". Nature. 240 (5383): 527–535. Bibcode:1972Natur.240..527H. doi:10.1038/240527a0. PMID 4568399.

- Nissani, M. (1975). "A new behavioral bioassay for an analysis of sexual attraction and pheromones in insects". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 192 (2): 271–5. doi:10.1002/jez.1401920217. PMID 805823.

- Hotta, Y., Benzer, S. (1976). "Courtship in Drosophila mosaics: sex-specific foci for sequential action patterns". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 73 (11): 4154–4158. Bibcode:1976PNAS...73.4154H. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.11.4154. PMC 431365. PMID 825859.

- Nissani, Moti (1977). "Cell lineage analysis of germ cells of Drosophila melanogaster". Nature. 265 (5596): 729–731. Bibcode:1977Natur.265..729N. doi:10.1038/265729a0. PMID 404558.

- Szabad, Janos, and Nothiger, Rolf (1992). "Gynandromorphs of Drosophila suggest one common primordium for the somatic cells of the female and male gonads in the region of abdominal segments 4 and 5" (PDF). Development. 115: 527–533.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gynandromorphs. |