Vicente Blasco Ibáñez

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez (29 January 1867 – 28 January 1928) was a journalist, politician and best-selling Spanish novelist in various genres whose most widespread and lasting fame in the English-speaking world is from Hollywood films adapted from his works.

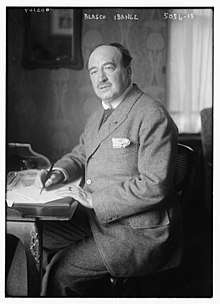

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez | |

|---|---|

Vicente Blasco Ibáñez in 1919 | |

| Born | Vicente Blasco Ibáñez 29 January 1867 Valencia, Spain |

| Died | 28 January 1928 (aged 60) Menton, France |

| Resting place | Valencia Cemetery |

| Language | Spanish |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Literary movement | Realism |

Biography

He was born in Valencia. At university, he studied law and graduated in 1888 but never went into practice. He was more interested in politics, journalism and literature. He was a particular fan of Miguel de Cervantes.

In politics he was a militant Republican partisan in his youth and founded the newspaper El Pueblo (translated as The People) in his hometown. The newspaper aroused so much controversy that it was taken to court many times. In 1896, he was arrested and sentenced to a few months in prison. He made many enemies and was shot and almost killed in one dispute. The bullet was caught in the clasp of his belt. He had several stormy love affairs.

He volunteered as the proofreader for the novel Noli Me Tangere, in which the Filipino patriot José Rizal expressed his contempt of the Spanish colonization of the Philippines. He traveled to Argentina in 1909 where two new cities, Nueva Valencia and Cervantes, were created. He gave conferences on historical events and Spanish literature. Tired and disgusted with government failures and inaction, Vicente Blasco Ibáñez moved to Paris at the beginning of World War I. When living in Paris, Ibáñez had been introduced to the poet and writer Robert W. Service by their mutual publisher Fisher Unwin, who asked Robert W. Service to act as an interpreter in the deal of a contract concerning Ibáñez.[1]

He was a supporter of the Allies in World War I.

He died in Menton, France in 1928, the day before his 61st birthday, in the residence of Fontana Rosa (also named the House of Writers, dedicated to Miguel de Cervantes, Charles Dickens and Honoré de Balzac) that he built.

Writing career

His first published novel was “La araña negra” ('The Black Spider') in 1892, an immature work that he later repudiated – a study of the connections between a noble Spanish family and the Jesuits throughout the 19th century. It seems to have been a vehicle for him to express his anti-clerical views.

In 1894, he published his first mature work, a novel called “Arroz y tartana” (Airs and Graces). The story is about a widow in late 19th century Valencia trying to keep up appearances in order to marry her daughters well. His next books consist of detailed studies of aspects of rural life in the farmlands of Valencia – the so-called huerta that the Moorish colonizers had created to grow crops such as rice, vegetables and oranges, with a carefully planned irrigation system in an otherwise arid landscape. The concern with depicting the details of this lifestyle qualifies Blasco Ibáñez as an example of Costumbrismo:

- Flor de mayo (1895) ('Mayflower')

- La barraca (novel) (1898)[2] ('The Hut')

- Entre naranjos (1900)[3] ('Between Orange Trees')

- Cañas y barro (1902)[4] ('Reeds and Mud')

These works also show the influence of Naturalism which he would most likely have assimilated through reading Émile Zola. The characters in these works are determined by the interaction of heredity, environment and social conditions – race, milieu, et moment – and the novelist is acting as a kind of scientist, drawing out the influences that are acting upon them at any given moment. They are powerful works but are sometimes flawed by heavy-handed didactic elements. For example, in La Barraca, the narrator often preaches the need for these ignorant people to be better-educated. There is also a strong political element – he shows how destructive it is for these poor farm-workers to be fighting each other rather than uniting against their true oppressors – the Church and the land-owners. However, alongside the preaching, there are lyrical and highly detailed accounts of how the irrigation canals are managed and of the workings of the age-old “tribunal de las aguas” – a court composed of farmers that meets weekly close by Valencia Cathedral to decide which farm gets to receive water when and which also arbitrates on disputes on access to water. “Cañas y barro” is often adjudged the masterpiece of this phase of Blasco Ibáñez’s writings.

After that, his writing changed markedly. He left behind costumbrismo and Naturalism and began to set his novels in more cosmopolitan locations than the huerta of Valencia. His plots became more sensational and melodramatic. Academic criticism of him in the English-speaking world has largely ignored these works, although they form by far the majority of his published output – some 30 works. Some of these works attracted the attention of Hollywood studios and became the basis of celebrated films.

Prominent among these is Sangre y arena (Blood and Sand, 1908), which follows the career of Juan Gallardo from his poor beginnings as a child in Seville, to his rise to celebrity as a matador in Madrid, where he falls under the spell of the seductive Doña Sol, which leads to his downfall. Ibáñez directed a 65-minute film version in 1916.[5] There are three remakes made in 1922, 1941 and 1989, respectively.

His greatest personal success probably came from the novel Los cuatro jinetes del Apocalipsis (The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse) (1916), which tells a tangled tale of the French and German sons-in-law of an Argentinian land-owner who find themselves fighting on opposite sides in the First World War. When this was filmed by Rex Ingram in 1921, it became the vehicle that propelled Rudolph Valentino to stardom.

Rex Ingram also filmed Mare Nostrum – a spy story from 1918 - in 1926 as a vehicle for his wife Alice Terry at his MGM studio in Nice. Michael Powell claimed in his memoirs that he had his first experience of working in films on that production.

A further two Hollywood films can be singled out, as they were the first films that were made by Greta Garbo following her arrival at MGM in Hollywood –The Torrent (based on Entre naranjos from 1900), and The Temptress (derived from La Tierra de Todos from 1922).

Works

- A los pies de Venus

- Argentina y sus grandezas

- Arroz y tartana at Project Gutenberg (1894)

- Cañas y barro,[6] about life among the fishermen-peasants of the Albufera marshes in Valencia. Also a Spanish TV series.

- Cuentos valencianos

- El caballero de la virgen

- El establo de Eva, short story (1902)

- El intruso, about immigration to the Basque Country

- El oriente

- El papa del mar, about the antipope Benedict XIII, who established his court at Peñíscola.

- El parásito del tren, short story (1902)

- El paraíso de las mujeres at Project Gutenberg

- El préstamo de la difunta at Project Gutenberg

- En busca del Gran Khan

- Entre naranjos,[7] another Valencian piece. Also a Spanish TV series.

- Fantasma de las alas de oro

- Flor de mayo

_La_ara%C3%B1a_negra%2C_tomo_I.png)

- La araña negra (1892)

- La Barraca at Project Gutenberg

- La bodega

- La Catedral at Project Gutenberg

- La familia de Doctor Pedraza (1922)

- La horda (1905)

- La maja desnuda, novel with title inspired on Goya's painting Nude "Maja".

- La Pared

- La reina Calafia (1924)

- La Tierra de Todos at Project Gutenberg

- Los argonautas

- The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Los Cuatro Jinetes del Apocalipsis),[8] about Argentina and the First World War. Several times filmed.[9] Bestseller in the United States in 1919.

- Los muertos mandan

- Luna Benamor

- Mare Nostrum, a spy novel in the Mediterranean. Filmed in 1926 and 1948.

- Novelas de la costa azul

- Blood and Sand (Sangre y arena), about a matador in a love triangle. Filmed several times.

- Vistas sudamericanas

- Voluntad de vivir

- Vuelta del mundo de un novelista, a travelogue

Works in English

- Mare Nostrum (Our Sea): A Novel. translator Charlotte Brewster Jordan. E.P. Dutton. 1919.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Blood and Sand: A Novel. translator W. A. Gillespe. E. P. Dutton. 1919.CS1 maint: others (link)

- La Bodega. translator Isaac Goldberg. E. P. Dutton. 1919.CS1 maint: others (link)<

- The Blood of the Arena. translator Frances Douglas. A. C. McClurg & Company. 1911.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Woman Triumphant (La Maja Desnuda). translator Hayward Keniston. E. P. Dutton. 1920.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Edmund R. Brown, ed. (1919). The Last Lion: And Other Tales. Branden Books. pp. 15–.

References

- "Robert W. Service (1874-1958) Poet & Adventurer: Vicente Blasco Ibáñez (1867-1928)".

- "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Obras Completas De V. Blasco Ibañez, by AUTHOR".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 10, 2006. Retrieved 2005-09-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 10, 2006. Retrieved 2005-09-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.filmaffinity.com/es/film321644.html

- "Wayback Machine" (PDF). 26 October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 October 2009.

- "Wayback Machine". 27 October 2009. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009.

- VICENTE BLASCO IBÁÑEZ, "LOS CUATRO JINETES DEL APOCALIPSIS". Archived from the original on October 26, 2009. Retrieved 2005-09-30.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

| Wikisource has the text of a 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article about "Vicente Blasco Ibáñez". |

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vicente Blasco Ibáñez. |

- Works by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Vicente Blasco Ibáñez at Internet Archive

- Works by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in the original Spanish with English translation

- Newspaper clippings about Vicente Blasco Ibáñez in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW