First Russian Art Exhibition

The First Russian Art Exhibition (German: Erste Russische Kunstausstellung Berlin) was the first exhibition of Russian art held in Berlin following the Russian Revolution. It opened at the Gallery van Diemen, 21 Unter den Linden, on Sunday 15 October 1922. The exhibition was hosted by the Soviet People's Commissariat for Education, and proved controversial in relationship to the current developments in avant-garde art in Russia, most notably Constructivism.

Preparations

In 1918 the Fine Arts section (IZO) of Narkompros established an International Bureau which included Nikolay Punin, David Shterenberg, Vladimir Tatlin and Vassily Kandinsky.[1] They worked Ludwig Baehr, an artistically inclined ex-Officer in the German Imperial Army. Baehr had been on the German negotiating team for the Treaty of Brest Litovsk and was subsequently assigned to making links with the Russian intelligentsia. He established links with the Novembergruppe and the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Workers' Council for Art). In particular he carried messages between Bruno Taut, Walter Gropius and Max Pechstein. However he was also importing books and printing presses into Russia against the policy laid down by the German Foreign Office, and after his arrest in late 1919, this channel of communication no longer worked. In 1921 they gave Kandinsky a mandate to organise an exhibition of contemporary Russian art in Berlin.[2] However following political and aesthetic differences, the organisation of the exhibition was delayed as different personnel came to take on responsibility for the exhibition. In the end it was organised by Shterenberg, by them Director of IZO, Nathan Altman, and Naum Gabo.

Catalogue

The Catalogue was published by Workers International Relief to raise money in response to a drought and famine in the Volga area, particularly those lands occupied by the Volga Germans. It featured a foreword with sections written by David Shterenberg, Edwin Redslob (in his capacity as Reichskunstwart) and Arthur Holitscher, who in 1921 had published an account of his visit to Soviet Russia.

Foreword

Shterenberg recounted how previous attempts by Russian artists to keep in touch with their western counterparts had been limited to the issuing of proclamations and manifestoes, but that with this exhibition a real step had been made to bring both groups together. The stated aim of the exhibition was to display the full story of the development of Russian art through both war and revolution. He referred to the transformative effect of the October Revolution in opening up art to mass of people, who had thus re-invigorated what had been the dead, official culture of "high art". This dynamic had also opened up new opportunities for Russia's creative forces, as their ideas could then be carried into the public spaces of towns and cities, which were being transformed by the revolution. There were new approaches being developed as regards urban decoration and architecture: the artist was no longer working in an isolated way, but rather in close contact with the people, who sometimes responded with enthusiasm and sometimes with scorn. Under these new testing circumstances some fell by the wayside, but others flourished. The limitation of the canvas, or the "stone coffins" which passed for housing were being swept away as the new society demanded a new environment.[3]

He continued that the immediately following the revolution the focus was on the decoration of public spaces, which however would be unsuitable for the exhibition. The exhibition thus focussed on the work of different movements active in Russia: the more traditional Union of Russian Artists, Mir Iskusstva, the Jack of Diamonds Group, the Impressionists and such leftist groups as the cubists, suprematists and the constructivists. Other exceptional work by artists who did not fit any of these groups was also included. Posters from the Russian Civil War had also been included, as had items from the State Porcelain factory. He also stated that the Soviet government sought German works of art to exhibit in Soviet Russia[3]

Redslob's contribution sought to balance the rooted-ness of artists in their own culture with a recognition of importance of contemporary issues in art. He described a shared responsibility for building Europe and said he was moved by the request for German art to be displayed in Russia.

Holitscher provided s statement where he suggested that artists were more able to communicate what was happening in a period of dissolution of one epoch and the emergence of another. Mentioning the art movements of the previous fifty years, he said that these should not be dismissed as "studio revolutions". He described how the coming of a spiritual revolution was first sensed by groups of precocious artists who would then be picked up by connoisseurs, collectors, dealers and museum directors, and even some snobs. Thus it becomes drawn into bourgeois society and the world of commercial cunning and social ambition. Only rarely does it become a matter of the pleasure and satisfaction of inner understanding. Nevertheless, it is the masses, whether fully or semiconsciously, who spur on the artist to new achievement. Thus the revolution which emerges from the artist's studio may not have as much impact as those who guide the political and economic interests of society, nevertheless there are periods when the enslavement of the masses has a greater role in the creative works of their contemporaries, even if the circumstances in which Praxiteles, Michelangelo or Dürer worked are no longer understood. In such times the artist has the power to shape the political and economic aspirations of the people.[4]

He continued that prior to a revolutionary transformation of society it was thought that the artist would be the first to embrace the new. However this is only partially true. The revolutionary artists is as much shaken as the rest of the general population, and only a few, singled out as human beings and as artists, follow their inner conviction and serve the destiny of the people. They attempt to link up with the masses while the "studio revolutionaries" stand on the sidelines, pretending to join in but in fact sabotaging the movement. While the new vision is becoming manifest in the public spaces of the streets, squares, bridges and barricades, becoming integrated into the vigorous life of the people, the "studio revolutionaries" crawl back to the haze of oil paint in their studios. The forward development of art is no longer dependent on the vision of a single prophetic man, but rather the natural urge of the people which rises up as a triumphant choir. The art theory born of the old individualised world is swept away by the victorious revolution. The art that arises in this way cannot be criticised in terms of artistic activity, but rather in terms of the political and economic circumstances which give rise to it. Such art will within itself create new aesthetic laws, will in itself mean revolution rather than simply a segment of revolution. "It will mean the totality of the creative forces of an epoch–not an isolated aspect of its many possible manifestations."[4]

Reception

- German: Paul Westheim: “The Exhibition of Russian Artists” (Originally published as “Die Ausstellung der Russen”), Das Kunstblatt (November 1922)[5]

- German: Adolf Behne “On the Russian Exhibition” (Originally published as “Der Staatsanwalt schüzt das Bild”), Die Weltbühne No. 47 (23 November 1922)[6]

- Hungarian: Alfréd Kemény: "Notes to the Russian Artists’ Exhibition in Berlin", (Originally published as “Jegyzetek az orosz mũvészek berlini kiállitáshoz,”), Egység (February, 1923)[7]

- Hungarian: Ernő Kállai: “The Russian Exhibition in Berlin” (Originally published as “A berlini orosz kiállfíás”, Akasztott Ember vol. 2 (February 15, 1923)][8]

- Serbo-Croat: Branko Ve Poljanski: “Through the Russian Exhibition” (Originally published as “Kroz rusku izložbu u berlinu”), Zenit vol. 3, no. 22 (March 1923)[9]

Artists exhibited

- Nathan Altmann: Russia, Petrokommuna, Painting

- Yury Annenkov (1889-1974): Forest

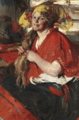

- Abram Arkhipov (1862-1930)): At the Market, Peasant Woman with Red Shawl,

- Vladimir Baranov-Rossine (1888–1944): Pink Colour

- David Burliuk (1882-1967):

Gallery

Peasant Woman with Red Shawl by Abram Arkhipov

Peasant Woman with Red Shawl by Abram Arkhipov Pink Colour by Vladimir Baranov-Rossine

Pink Colour by Vladimir Baranov-Rossine.jpg) Suprematism (1916) by Kazimir Malevich

Suprematism (1916) by Kazimir Malevich

References

- Peter Nisbet (1983). The 1st Russian Show: A Commemoration of the Van Diemen Exhibition Berlin, 1922. London: Anneley Juda Fine Art.

- Enke, Roland. "Malevich and Berlin – An Approach by Roland Enke". www.db-artmag.com. Deutsche Bank AG. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- Shterenberg, David (1974). "Foreword". The Tradition of Constructivism: 70–72.

- Holitscher, Arthur (1974). "Foreword". The Tradition of Constructivism: 72–74.

- Westheim, Paul. "The Exhibition of Russian Artists". modernist architecture. Ross Wolfe. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Behne, Adolf. "On the Russian Exhibition". modernist architecture. Ross Wolfe. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Kemény, Alfréd. "Notes to the Russian Artists' Exhibition in Berlin". modernist architecture. Ross Wolfe. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Kállai, Ernő. "The Russian Exhibition in Berlin". modernist architecture. Ross Wolfe. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Poljanski, Branko Ve. "Through the Russian Exhibition". modernist architecture. Ross Wolfe. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to First Russian Art Exhibition. |