Nadezhda Udaltsova

Nadezhda Andreevna Udaltsova (Russian: Наде́жда Андре́евна Удальцо́ва, December 29,1885 – January 25,1961) was a Russian avant-garde artist (Cubist, Suprematist), painter and teacher.[1]

Nadezhda Andreevna Udaltsova | |

|---|---|

Nadezhda Udaltsova, 1915 | |

| Born | December 29, 1885 |

| Died | January 25, 1961 (aged 75) Moscow, Russia |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Education | Académie de La Palette |

| Known for | Painting |

Early life and education

Nadezhda Udaltsova was born in the village of Orel, Russia, on December 29, 1885. When she was six, her family moved to Moscow, where she graduated from high school and began her artistic career.[2] In September 1905 Udaltsova enrolled in the art school run by Konstantin Yuon and Ivan Dudin, where she studied for two years and met fellow-students Vera Mukhina, Liubov Popova, and Aleksander Vesnin. In the spring of 1908 she traveled to Berlin and Dresden, and upon her return to Russia, she unsuccessfully applied for admission to the Moscow Institute of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture. In 1910–11, Udaltsova studied at several private studios, among them Tatlin's Tower. In 1912–13 she and Popova traveled to Paris to continue their studies under the tutelage of Henri Le Fauconnier, Jean Metzinger and André Segonzac at Académie de La Palette.[3] Udaltsova returned to Moscow in 1913 and worked in Vladimir Tatlin's studio together with Popova, Vesnin, and others.[4]

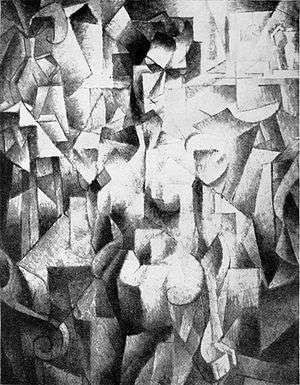

Cubism and Cubo-Futurism

Udaltsova's professional debut was as a participant in a Jack of Diamonds exhibition in Moscow in the winter of 1914.[5] But it was in 1915 that she really made her name as a Cubist artist, participating in three major exhibitions in that single year, including "Tramway V" (February), "Exhibition of Leftist Tendencies" (April), and "The Last Futurist Exhibition: 0.10" (December).[6] Her paintings were subsequently collected and exhibited in the 1920s by the Tretiakov Gallery, the Russian Museum, and other venues as examples of Cubo-Futurism.[7]

Suprematism

Under the influence of Tatlin, Udaltsova experimented with Constructivism, but eventually embraced the more painterly approach of the Suprematist movement.[8] In 1916, she participated with other Suprematist artists in a Jack of Diamonds exhibition, and during that same time period she joined Kazimir Malevich's Supremus group. In 1915–1916, together with other suprematist artists (Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandra Ekster, Liubov Popova, Nina Genke, Olga Rozanova, Ivan Kliun, Ivan Puni, Ksenia Boguslavskaya and others) worked at the Verbovka Village Folk Centre.[9]

Revolution

Like many of her avant-garde contemporaries, Udaltsova embraced the October Revolution. In 1917, she was elected to the Club of the Young Leftist Federation of the Professional Union of Artists and Painters and began work in various state cultural institutions, including the Moscow Proletkult. In 1918, she joined the Free State Studios, first working as Malevich's assistant, and then heading up her own studio. She also collaborated with Aleksei Gan, Aleksei Morgunov, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Malevich on a newspaper entitled Anarkhiia (Anarchy).[10] In 1919, Udaltsova contributed eleven works from the time she was working in Tatlin's studio to the "Fifth State Exhibition." She also married her second husband, the painter Alexander Drevin. When Vkhutemas, the Russian state art and technical school, was established in 1920, she was appointed professor and senior lecturer and would remain on staff until 1934.[11] In 1920 she also became a member of the Institute for Artistic Culture (InKhuK) and actively participated in discussions there on the fate of easel art. However, when the Institute endorsed Constructivism and declared the end of easel painting, she resigned her membership in protest in 1921.[12]

Fauvism and a return to the figurative

In the early 1920s, Udaltsova's work began to show a turn away from the radical avant-garde and a sensibility more aligned with artists associated with the Jack of Diamonds, among them Ilya Mashkov, Petr Konchalovsky and Aristarkh Lentulov, exhibiting her Fauvist portraits and landscapes alongside them at the Vkhutemas "Exhibition of Paintings" of 1923 and also at the Venice "Biennale" of 1924.[13] She also continued to teach, including instruction in textile design at Vhkutemas and the Textile Institute in Moscow from 1920 until 1930.

Under the influence of Drevin, Udaltsova returned to nature and began painting landscapes. Between 1926 and 1934 they traveled widely, painting the Ural and Altai Mountains, as well as landscapes in Armenia and Central Asia.[14] From 1927 to 1935, she contributed to national and international exhibitions and participated with Drevin in joint exhibitions at the Russian Museum (1928) and in Erevan, Armenia (1934).[15]

Repression and rehabilitation

In 1932–33, Udaltsova's contributions to the exhibition of "Artists of the RSFSR Over the Last Fifteen Years" were publicly criticized for so-called "formalist tendencies."[16] In 1938 Alexander Drevin was arrested and executed by the NKVD, and Udaltsova became a persona non grata in the world of Soviet art. She was allowed a solo exhibition at the Moscow Union of Soviet Artists in 1945, and after Stalin's death, she contributed to a group exhibition at Moscow's House of the Artist in October 1958.[17]

Udaltsova died in 1961 in Moscow.[18]

Influence

The Udaltsova crater on Venus is named after her. Her son was the prominent Russian sculptor Andrei Drevin (1921–1996).

References

- "Nadezhda Udaltsova". rusartnet.com. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Yablonskaya, M.N.; edited [and translated from the Russian] by Anthony Parton (1990). Women artists of Russia's new age, 1900-1935 (1 ed.). New York: Rizzoli. p. 157. ISBN 0-8478-1090-9.

- Yablonskaya, M.N.; edited [and translated from the Russian] by Anthony Parton (1990). Women artists of Russia's new age, 1900-1935 (1 ed.). New York: Rizzoli. p. 158. ISBN 0-8478-1090-9.

- Rakitin,Vasilii (2000). "Nadezhda Udaltsova". In Bowlt, John E.; Drutt, Matthew (eds.). Amazons of the avant-garde : Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova. New York: Guggenheim Museum. p. 278. ISBN 0-8109-6924-6.

- Rakitin,Vasilii (2000). "Nadezhda Udaltsova". In Bowlt, John E.; Drutt, Matthew (eds.). Amazons of the avant-garde : Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova. New York: Guggenheim Museum. p. 271. ISBN 0-8109-6924-6.

- Yablonskaya, M.N.; edited [and translated from the Russian] by Anthony Parton (1990). Women artists of Russia's new age, 1900-1935 (1 ed.). New York: Rizzoli. p. 159. ISBN 0-8478-1090-9.

- Rakitin,Vasilii (2000). "Nadezhda Udaltsova". In Bowlt, John E.; Drutt, Matthew (eds.). Amazons of the avant-garde : Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova. New York: Guggenheim Museum. p. 272. ISBN 0-8109-6924-6.

- Yablonskaya, M.N.; edited [and translated from the Russian] by Anthony Parton (1990). Women artists of Russia's new age, 1900-1935 (1 ed.). New York: Rizzoli. p. 169. ISBN 0-8478-1090-9.

- Malevich, by Gerry Souter, page 176

- Rakitin,Vasilii (2000). "Nadezhda Udaltsova". In Bowlt, John E.; Drutt, Matthew (eds.). Amazons of the avant-garde : Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova. New York: Guggenheim Museum. p. 278. ISBN 0-8109-6924-6.

- Yablonskaya, M.N.; edited [and translated from the Russian] by Anthony Parton (1990). Women artists of Russia's new age, 1900-1935 (1 ed.). New York: Rizzoli. p. 169. ISBN 0-8478-1090-9.

- Yablonskaya, M.N.; edited [and translated from the Russian] by Anthony Parton (1990). Women artists of Russia's new age, 1900-1935 (1 ed.). New York: Rizzoli. p. 169-70. ISBN 0-8478-1090-9.

- Yablonskaya, M.N.; edited [and translated from the Russian] by Anthony Parton (1990). Women artists of Russia's new age, 1900-1935 (1 ed.). New York: Rizzoli. p. 170. ISBN 0-8478-1090-9.

- Yablonskaya, M.N.; edited [and translated from the Russian] by Anthony Parton (1990). Women artists of Russia's new age, 1900-1935 (1 ed.). New York: Rizzoli. p. 170. ISBN 0-8478-1090-9.

- Rakitin,Vasilii (2000). "Nadezhda Udaltsova". In Bowlt, John E.; Drutt, Matthew (eds.). Amazons of the avant-garde : Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova. New York: Guggenheim Museum. p. 279. ISBN 0-8109-6924-6.

- Rakitin,Vasilii (2000). "Nadezhda Udaltsova". In Bowlt, John E.; Drutt, Matthew (eds.). Amazons of the avant-garde : Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova. New York: Guggenheim Museum. p. 279. ISBN 0-8109-6924-6.

- Rakitin,Vasilii (2000). "Nadezhda Udaltsova". In Bowlt, John E.; Drutt, Matthew (eds.). Amazons of the avant-garde : Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova. New York: Guggenheim Museum. p. 279. ISBN 0-8109-6924-6.

- The Magical Chorus: A History of Russian Culture from Tolstoy to Solzhenitsyn, by Solomon Volkov, page 70