Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia (French: [fʁɑ̃sis pikabja]: born Francis-Marie Martinez de Picabia; 22 January 1879 – 30 November 1953) was a French avant-garde painter, poet and typographist. After experimenting with Impressionism and Pointillism, Picabia became associated with Cubism. His highly abstract planar compositions were colourful and rich in contrasts. He was one of the early major figures of the Dada movement in the United States and in France. He was later briefly associated with Surrealism, but would soon turn his back on the art establishment.[1]

Francis Picabia | |

|---|---|

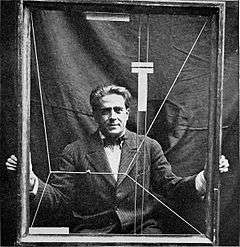

Francis Picabia, 1919, inside Danse de Saint-Guy | |

| Born | Francis-Marie Martinez Picabia 22 January 1879 Paris, France |

| Died | 30 November 1953 (aged 74) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | Amorous Parade |

| Movement | Cubism, Abstract art, Dada, Surrealism |

Biography

Early life

Francis Picabia was born in Paris of a French mother and a Cuban father who was an attaché at the Cuban legation in Paris. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was seven. Some sources would have his father as of aristocratic Spanish descent, whereas others consider him of non-aristocratic Spanish descent, from the region of Galicia.[2] Financially independent, Picabia studied under Fernand Cormon and others at the École des Arts Decoratifs in the late 1890s.

In 1894, Picabia financed his stamp collection by copying a collection of Spanish paintings that belonged to his father, switching the originals for the copies, without his father's knowledge, and selling the originals. Fernand Cormon took him into his academy at 104 boulevard de Clichy, where Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec had also studied. From the age of 20, he lived by painting; he subsequently inherited money from his mother.

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_290_x_300_cm%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_National_d%E2%80%99Art_Moderne%2C_Centre_Georges_Pompidou%2C_Paris..jpg)

In the beginning of his career, from 1903 to 1908, Picabia was influenced by the Impressionist paintings of Alfred Sisley. Little churches, lanes, roofs of Paris, riverbanks, wash houses, lanes, barges—these were his subject matter. Some however, began to question his sincerity and said he copied Sisley, or that his cathedrals looked like Monet, or that he painted like Signac.[3] From 1909, he came under the influence of those that would soon be called Cubists and later form the Golden Section (Section d'Or). The same year, he married Gabrielle Buffet.

Around 1911 Picabia joined the Puteaux Group, members of which he met at the studio of Jacques Villon in Puteaux; a commune in the western suburbs of Paris. There he became friends with artist Marcel Duchamp and close friends with Guillaume Apollinaire. Other group members included Albert Gleizes, Roger de La Fresnaye, Fernand Léger and Jean Metzinger.

Proto-Dada

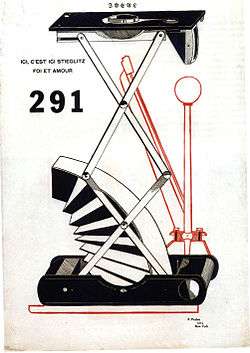

Picabia was the only member of the Cubist group to personally attend the Armory Show, and Alfred Stieglitz gave him a solo show, Exhibition of New York studies by Francis Picabia, at his gallery 291 (formerly Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession), 17 March – 5 April 1913.

From 1913 to 1915 Picabia traveled to New York City several times and took active part in the avant-garde movements, introducing Modern art to America. When he landed in New York in June 1915, though it was ostensibly meant to be a simple port of call en route to Cuba to buy molasses for a friend of his—the director of a sugar refinery—the city snapped him up and the stay became prolonged.

The magazine 291 devoted an entire issue to him, he met Man Ray, Gabrielle and Duchamp joined him, drugs and alcohol became a problem and his health declined. He suffered from dropsy and tachycardia.[4] These years can be characterized as Picabia's proto-Dada period, consisting mainly of his portraits mécaniques.

Manifesto

Later, in 1916, while in Barcelona and within a small circle of refugee artists that included Albert Gleizes and his wife Juliette Roche, Marie Laurencin, Olga Sacharoff, Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay, he started his Dada periodical 391 (published by Galeries Dalmau), modeled on Stieglitz's own periodical. He continued the periodical with the help of Marcel Duchamp in the United States. In Zurich, seeking treatment for depression and suicidal impulses, he had met Tristan Tzara, whose radical ideas thrilled Picabia. Back in Paris, and now with his mistress Germaine Everling, he was in the city of "les assises dada" where André Breton, Paul Éluard, Philippe Soupault and Louis Aragon met at Certa, a Basque bar in the Passage de l'Opera. Picabia, the provocateur, was back home.

%2C_Dada_4-5%2C_Number_5%2C_15_May_1919.jpg)

Picabia continued his involvement in the Dada movement through 1919 in Zürich and Paris, before breaking away from it after developing an interest in Surrealist art. (See Cannibale, 1921.) He denounced Dada in 1921, and issued a personal attack against Breton in the final issue of 391, in 1924.

The same year, he put in an appearance in the René Clair surrealist film Entr'acte, firing a cannon from a rooftop. The film served as an intermission piece for Picabia's avant-garde ballet, Relâche, premiered at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, with music by Erik Satie.[5]

Later years

In 1922, André Breton relaunched Littérature magazine with cover images by Picabia, to whom he gave carte blanche for each issue. Picabia drew on religious imagery, erotic iconography, and the iconography of games of chance.[6]

In 1925, Picabia returned to figurative painting, and during the 1930s became a close friend of the modernist novelist Gertrude Stein. In the early 1940s he moved to the South of France, where his work took a surprising turn: he produced a series of paintings based on the nude glamour photos in French "girlie" magazines like Paris Sex-Appeal, in a garish style which appears to subvert traditional, academic nude painting. Some of these went to an Algerian merchant who sold them, and so it passed that Picabia came to decorate brothels across North Africa under the Occupation.

Before the end of World War II, he returned to Paris where he resumed abstract painting and writing poetry. A large retrospective of his work was held at the Galerie René Drouin in Paris in the spring of 1949. Francis Picabia died in Paris in 1953 and was interred in the Cimetière de Montmartre.

Legacy

Public collections holding works by Picabia include the Museum of Modern Art and Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York; the Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Art Institute of Chicago; the Tate Gallery, London; the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris; and Museum de Fundatie, Zwolle, Netherlands.

From 6 June through to 25 September 2016 at Kunsthaus Zürich and then from 21 November 2016 through 19 March 2017, the first retrospective of Picabia's work in the United States, Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction, took place at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, co-curated by Anne Umland and Cathérine Hug.[7] The retrospective was widely discussed by international art critics such as Philippe Dagen from Le Monde.[8]

Among the artists influenced by Picabia's work are the American artists David Salle and Julian Schnabel, the German artist Sigmar Polke, and the Italian artist Francesco Clemente.[9][10][11][12] in 1996, French artist Jean-Jacques Lebel initiated and co-curated the exhibition Picabia, Dalmau 1922 (with reference to Picabia's solo exhibition at Galeries Dalmau in 1922) shown at Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Barcelona and the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou. In 2002, the artists Peter Fischli & David Weiss installed Suzanne Pagé's retrospective devoted to Picabia at the musée d'art moderne de la ville de Paris (MAMVP). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, organized a major retrospective of his entire career, shown from 21 November 2016 to 19 March 2017.[13]

Art market

In 2003, a Picabia painting once owned by André Breton sold for US$1.6 million.[14]

On 16 November 2013, at Sotheby's Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale in New York, Picabia's Volucelle II (c. 1922, Ripolin on canvas, 198,5 x 249 cm) sold for US$8,789,000.[15]

Gallery

Francis Picabia in his studio c.1912

Francis Picabia in his studio c.1912 Caoutchouc, 1909, oil on canvas

Caoutchouc, 1909, oil on canvas Horses, 1911, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 92.5 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Published in the New York Times, New York, 16 February 1913, Page 121

Horses, 1911, oil on canvas, 73.3 x 92.5 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Published in the New York Times, New York, 16 February 1913, Page 121%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_50.3_%C3%97_61.5_cm%2C_private_collection.jpg) Paysage à Cassis (Landscape at Cassis), 1911–12, oil on canvas, 50.3 × 61.5 cm, private collection

Paysage à Cassis (Landscape at Cassis), 1911–12, oil on canvas, 50.3 × 61.5 cm, private collection Tarentelle, 1912, oil on canvas, 73.6 x 92.1 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme" by Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, published in 1912

Tarentelle, 1912, oil on canvas, 73.6 x 92.1 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Reproduced in Du "Cubisme" by Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, published in 1912 The Procession, Seville, 1912, oil on canvas, 121.9 x 121.9 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

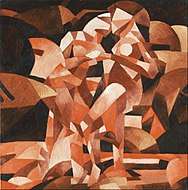

The Procession, Seville, 1912, oil on canvas, 121.9 x 121.9 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC. The Dance at the Spring, 1912, oil on canvas, 120.5 x 120.6 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show

The Dance at the Spring, 1912, oil on canvas, 120.5 x 120.6 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_300.4_x_300.7_cm%2C_Art_Institute_of_Chicago.jpg) Edtaonisl (Ecclesiastic), 1913, oil on canvas, 300.4 x 300.7 cm, Art Institute of Chicago

Edtaonisl (Ecclesiastic), 1913, oil on canvas, 300.4 x 300.7 cm, Art Institute of Chicago Catch as Catch Can, 1913, oil on canvas, 100.6 x 81.6 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

Catch as Catch Can, 1913, oil on canvas, 100.6 x 81.6 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art Star Dancer on a Transatlantic Steamer, 1913

Star Dancer on a Transatlantic Steamer, 1913 Force Comique, 1913-14, watercolor and graphite on paper, 63.4 x 52.7 cm, Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA

Force Comique, 1913-14, watercolor and graphite on paper, 63.4 x 52.7 cm, Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, MA

%2C_work_on_paper%2C_47.4_x_31.7_cm%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_d'Orsay.jpg) Fille née sans mère (Girl Born Without a Mother), 1915, work on paper, 47.4 x 31.7 cm, Musée d'Orsay

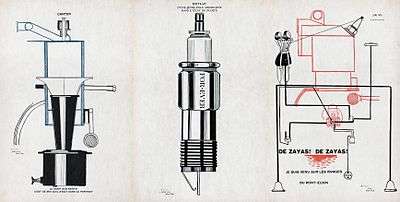

Fille née sans mère (Girl Born Without a Mother), 1915, work on paper, 47.4 x 31.7 cm, Musée d'Orsay.jpg) Voilà Haviland (La poésie est comme lui), Portrait mécanomorphe de Paul B. Haviland, 1915, Musée d'Orsay

Voilà Haviland (La poésie est comme lui), Portrait mécanomorphe de Paul B. Haviland, 1915, Musée d'Orsay- Prostitution Universelle (Universal Prostitution), 1916-17, black ink, tempera, metallic paint on cardboard, 74.5 x 94.2 cm, Yale University Art Gallery

%2C_ink_on_paper%2C_31.8_x_23_cm%2C_Tate%2C_London.jpg) Réveil Matin (Alarm Clock), 1919, ink on paper, 31.8 x 23 cm, Tate, London

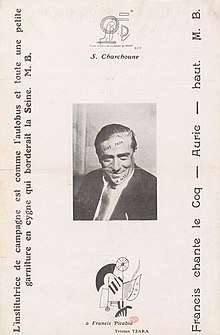

Réveil Matin (Alarm Clock), 1919, ink on paper, 31.8 x 23 cm, Tate, London Dada Movement, Dada, Number 5, 15 May 1919

Dada Movement, Dada, Number 5, 15 May 1919 Portrait of Cézanne, Portrait of Renoir, Portrait of Rembrandt, 1920, Toy monkey and oil on cardboard, 39.4 x 55 cm, Reproduced in Cannibale, Paris, n. 1, April 25, 1920

Portrait of Cézanne, Portrait of Renoir, Portrait of Rembrandt, 1920, Toy monkey and oil on cardboard, 39.4 x 55 cm, Reproduced in Cannibale, Paris, n. 1, April 25, 1920%2C_ink_and_graphite_on_paper%2C_33_x_24_cm%2C_Mus%C3%A9e_National_d'Art_Moderne%2C_Paris.jpg) La Sainte Vierge (The Blessed Virgin), 1920, ink and graphite on paper, 33 x 24 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

La Sainte Vierge (The Blessed Virgin), 1920, ink and graphite on paper, 33 x 24 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris Francis Picabia, 1921, L'oeil cacodylate, oil and collage on canvas, 148.6 x 117.4 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

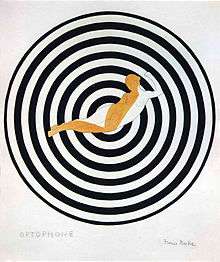

Francis Picabia, 1921, L'oeil cacodylate, oil and collage on canvas, 148.6 x 117.4 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris Optophone I, c. 1921-22, ink, acrylic, and graphite on paper, 72 x 60 cm. Reproduced in Galeries Dalmau, Picabia, exhibition catalogue, Barcelona, Nov. 18 - Dec. 8, 1922

Optophone I, c. 1921-22, ink, acrylic, and graphite on paper, 72 x 60 cm. Reproduced in Galeries Dalmau, Picabia, exhibition catalogue, Barcelona, Nov. 18 - Dec. 8, 1922 Espagnole et agneau de l'apocalypse, c. 1927-28, gouache, watercolour and brush and ink on paper, 65 × 50 cm, private collection

Espagnole et agneau de l'apocalypse, c. 1927-28, gouache, watercolour and brush and ink on paper, 65 × 50 cm, private collection- Hera, c. 1929, oil on cardboard, 105 × 75 cm, private collection

Transparence - Sphinx, 1929, oil on canvas, 131 × 163 cm, Centre Georges Pompidou

Transparence - Sphinx, 1929, oil on canvas, 131 × 163 cm, Centre Georges Pompidou

Bibliography

- Allan, Kenneth R. “Metamorphosis in 391: A Cryptographic Collaboration by Francis Picabia, Man Ray, and Erik Satie.” Art History 34, No. 1 (February, 2011): 102-125.

- Baker, George. The Artwork Caught by the Tail: Francis Picabia and Dada in Paris. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007. (ISBN 978-0-262-02618-5)

- Borràs, Maria Lluïsa. Picabia. Trans. Kenneth Lyons. New York: Rizzoli, 1985.

- Calté, Beverly and Arnauld Pierre. Francis Picabia. Tokyo: APT International, 1999.

- Camfield, William. Francis Picabia: His Art, Life and Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

- Hopkins, David. “Questioning Dada’s Potency: Picabia’s ‘La Sainte Vierge’ and the Dialogue with Duchamp.” Art History 15, No. 3 (September 1992): 317-333.

- Legge, Elizabeth. “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Virgin: Francis Picabia’s La Sainte Vierge.” Word & Image 12, No. 2 (April–June 1996): 218-242.

- Page, Suzanne, William Camfield, Annie Le Brun, Emmanuelle de l’Ecotais, et al., Francis Picabia: Singulier ideal. Paris: Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, 2002.

- Picabia, Francis. I Am a Beautiful Monster: Poetry Prose, and Provocation. Trans. Marc Lowenthal, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007. (ISBN 978-0-262-16243-2)

- Pierre, Arnauld. Francis Picabia: La peinture sans aura. Paris: Gallimard, 2002.

- Wilson, Sarah. "Francis Picabia: Accommodations of Desire - Transparencies 1924-1932." New York: Kent Fine Art, 1989. (ISBN 1-878607-04-9)

Dada is the groundwork to abstract art and sound poetry, a starting point for performance art, a prelude to postmodernism, an influence on pop art, a celebration of antiart to be later embraced for anarcho-political uses in the 1960s and the movement that lay the foundation for Surrealism.

—Marc Lowenthal, translator's introduction to Francis Picabia's I Am a Beautiful Monster: Poetry, Prose, And Provocation

References

- Marianne Heinz, Grove Art Online, MoMA, 2009 Oxford University Press

- Javier de Castromori (28 September 2008), Picabia, ¿pintor cubano?, La Voz de Galicia from 3 May 2004 quoted on www.penultimosdias.com, retrieved 26 January 2010

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) online biography, retrieved June 15, 2009

- Paris Match No 2791

- Chris, Joseph (14 February 2008). "After 391:Picabia's Early Multimedia Experience". Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Mark Polizzotti, Revolution of the Mind, (1995) pages 93-94, 160, 173, 196.

- English Press release to be found under http://www.kunsthaus.ch/fileadmin/templates/kunsthaus/pdf/medienmitteilungen/2016/mm2_picabia_e.pdf Archived 2017-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

- https://www.lemonde.fr/culture/article/2016/07/09/francis-picabia-la-peinture-a-vive-allure_4966835_3246.html

- The Editors of ARTnews (7 October 2016). "Then and Now: Picabia, Grasshopper of Modern Art". artnews.com. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- http://ropac.net/exhibition/david-salle-francis-picabia

- Kimmelman, Michael. "Review/Art; Picabia's 'Transparences': Layers of Many Meanings". nytimes.com. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- Kimmelman, Michael. "ART VIEW; What Is Sigmar Polke Laughing About?". nytimes.com. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Jason Rosenfeld, "Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction," The Brooklyn Rail, December 2016/January 2017 | Museum of Modern Art". brooklynrail.org. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- "Surrealist sale smashes records". 18 April 2003. Retrieved 21 March 2018 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Francis Picabia, Volucelle II, c. 1922, Ripolin on canvas, 198,5 x 249 cm, US$8,789,000. Sotheby's, Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale, New York, Wednesday, 6 November 2013

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Francis Picabia. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Francis Picabia |

- Picabia's Cats

- Comité Picabia; the organization developing a catalogue raisonné of the artist

- Picabia images at CGFA

- Scans of Picabia's publication, 391

- After 391: Picabia's early multimedia experiments Short essay

- Dada Movement in the MoMA Online Collection

- Francis Picabia. Machines and Spanish Women Exhibition at Fundació Antoni Tàpies

- "Francis Picabia, the Playboy Prankster of Modernism", New York Times

- detailed biography notes of Picabia and his connection with Dada

- Francis Picabia: Materials and Techniques; publication of the MoMA