Léonce Rosenberg

Léonce Rosenberg (12 September 1879 in Paris – 31 July 1947 in Neuilly-sur Seine) was an art historian, art collector, publisher and one of the most influential French art dealers of the 20th century. The son of an antique dealer Alexander Rosenberg and brother of the gallery owner Paul Rosenberg (21 rue de la Boétie, Paris), Léonce, a prominent gallery owner in Paris at the end of World War I, would become one of the world's major dealers of Modern art.

Leaving the family-owned gallery in 1910 Léonce opened his own business called Haute Epoque at 19 rue de La Baume, Paris. As an antiquarian Rosenberg began buying works by Cubist artists. By 1914 his collection included works by Pablo Picasso, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Auguste Herbin, and Juan Gris. After serving in World War I (1916-1917) he pursued his interests and represented these and other artists, and by the end of the war opened a new show space, Galerie de L'Effort Moderne.[1]

Biography

Léonce Rosenberg studied in London and Antwerp visiting galleries and museums in his free time. After returning to Paris he worked with his brother Paul in the family business. In 1906 Léonce and his brother inherited the family gallery on Avenue de l'Opéra which had been in existence for twenty years. His brother Paul was largely engaged in 19th- and early 20th-century art.

Léonce Rosenberg was an early advocate of Cubism, and would remain so throughout the 1920s and 1930s. He discovered the works of avant-garde artists in 1911 through the Salon des Indépendants, the art dealer Wilhelm Uhde, and in 1912 at the gallery of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler.

At the outset of World War I many German nationals living in France had their possessions sequestered by the French state. As a German citizen Kahnweiler took refuge in Switzerland and ran out of funds. With his art collection the hand of the French government he could no longer support his artists. Following the advice of Max Jacob and André Level (known for his well informed art investments), Léonce Rosenberg began amassing his collection. Just before the outbreak of World War I Rosenberg purchased 15 Cubist works by Picasso for 12,000 FF. His collection would soon include 20 works by Picasso, 10 by Georges Braque, 5 by Juan Gris and 20 by Auguste Herbin.[2][3]

Very quickly and despite his lack of experience Rosenberg became the official dealer of the Cubists purchasing works, in addition to those he already owned, by artist such as Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Joseph Csaky, Henri Laurens, Georges Valmier and Henri Hayden. Throughout World War I Rosenberg served as a moral and financial supporter of these artists. 'Without him' noted Max Jacob, 'a number of painters would be drivers or factory workers'.[3]

Picasso eventually switched over to his brother Paul Rosenberg's gallery, who would become his dealer Entre Deux Guerres.

Rosenberg volunteered for military service in 1915. He moved into a house at rue Marthe Édouard in Meudon near the military base, but also retained his Paris apartment at 22 rue Lavoisier and his Hôtel particulier 19 Rue de la Baume in the 8th arrondissement of Paris. During his periods of leave he continued to purchase Cubist works. From May, 1916, Rosenberg worked outside his unit as an English interpreter at the field headquarters of the Allied forces on the Somme front. During leave at the end of 1916 Rosenberg, through the intermediary of Juan Gris, went to Gino Severini's studio and bought a large painting of Woman Reading; possibly Severini's 1916 Femme lisant (Jeanne dans l’atelier; La lecture n. 1). The death of Umberto Boccioni during the month of August 1916 marked Severini's rupture from Futurism and his move closer to the Cubists.[4]

Galerie de L'Effort Moderne

In March 1917, the second line of defense cleared Rosenberg's unit moved to Le Havre. In July of the same year Rosenberg returned to his old unit, now stationed at an airport in Nanterre. Closer to Paris, Rosenberg decided to reopen his gallery.[2]

With the support given by Léonce Rosenberg, Cubism reemerged as a central issue for artists after four years of war. Rosenberg found himself financially ruined but exhibited the works he owned at his newly opened Galerie de L'Effort Moderne (also known as Galerie Léonce Rosenberg)[6] at 19, rue de la Baume, located in the elegant and fashionable 8th arrondissement of Paris. The gallery was open to all forms of Cubist and Abstract art. What followed would be a series of major one-man exhibitions—including works created between 1914 and 1918 by almost all the major Cubists.[7]

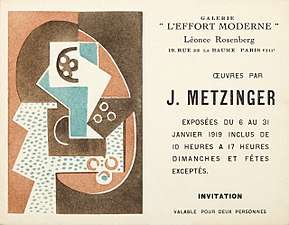

The first solo exhibition was held in March 1918, featuring works by Auguste Herbin.[8] In December of the same year, Rosenberg launched a series of Cubist exhibitions, beginning with Henri Laurens, followed in January 1919 with an exhibition of Cubist paintings by Jean Metzinger, Fernand Léger in February, Georges Braque in March, Juan Gris April, Gino Severini May, and Pablo Picasso in June, marking the climax of the campaign. This well-orchestrated program showed that Cubism was still very much alive, despite claims by critics to the contrary,[9] and it would remain so for at least a half-decade. Missing from this sequence of exhibitions were Jacques Lipchitz (who would exhibit in 1920), and those who had left France during the Great War: Robert Delaunay and Albert Gleizes most obviously. Nonetheless, according to art historian Christopher Green, "this was an astonishingly complete demonstration that Cubism had not only continued between 1914 and 1917, having survived the war, but was still developing in 1918 and 1919 in its "new collective form" marked by "intellectual rigor". In the face of such a display of vigour, it really was difficult to maintain convincingly that Cubism was even close to extinction".[7]

Rosenberg also organized literary and musical events in his gallery.[10]

The art collections of Kahnweiler and Uhde sequestered at the outset of World War I (which included works by Georges Braque, Raoul Dufy, Juan Gris, Auguste Herbin, Marie Laurencin, Fernand Léger, Jean Metzinger, Pablo Picasso, Jean Puy and Henri Rousseau) were sold by the government in a series of auctions at the Hôtel Drouot in 1921.[11][12] Rosenberg had himself appointed as 'expert' for the sales.

From 1924 to 1927, Rosenberg made his activities known through his Bulletin de l'Effort moderne (Éditions de l'effort moderne), a publication featuring writings and illustrations by contributors such as Léonce Rosenberg, Albert Gleizes, Piet Mondrian, Gino Severini.[13]

In 1928 Rosenberg moved his personal collection to his apartment rue de Longchamp, Paris, and commissioned the artists he championed to realize decorative panels. Giorgio de Chirico painted large panels for his living room.[14] After 1928 exhibitions became sporadic, featuring solo exhibitions by de Chirico, Metzinger, and Valmier.[8]

Rosenberg commissioned Albert Gleizes (replacing Gino Severini) in 1929 to paint decorative panels for his Parisian residence. They were installed in 1931.[15]

In 1930 and 1932, the Galerie de L'Effort Moderne presented two large exhibitions of works by Francis Picabia.[8]

A veritable center of activity and interest during the rise of modern art, the Galerie de L'Effort Moderne closed permanently in 1941, as a result of anti-Semitic laws and by the threat of the Nazi occupation of France. Eventually, the Nazi authorities looted some of his collection.[8] The gallery was not reopened following the war due primarily to Rosenberg's death in July 1947.[8]

Selected exhibitions

- Auguste Herbin, 1 – 22 March 1918

- Henri Laurens, 5 – 31 December 1918

- Jean Metzinger, 6 – 31 January 1919

- Fernand Léger, 5 – 28 February 1919

- Georges Braque, 5 – 31 March 1919

- Juan Gris, 5 – 30 April 1919

- Gino Severini, 5 – 31 May 1919

- Pablo Picasso, 5 – 25 June 1919

- Drawings, Gouaches, watercolors, ? – 29 November 1919: Blanchard, Braque, Csaky, Gris, Hayden, Herbier, Lagut, Laurens, Léger, Lipchitz, Metzinger, Picasso, Severini

- Henri Hayden, 4 – 24 December 1919

- Jacques Lipchitz, 26 January – 14 February 1920

- Juan Gris, 12 March – 2 April 1920

- Les Maîtres du Cubisme: Georges Braque, Juan Gris, Auguste Herbin, Henri Laurens, Fernand Léger, Jean Metzinger, Pablo Picasso, Gino Severini. Exhibition 3 May – 30 October 1920

- Léopold Survage, 2 – 25 November 1920

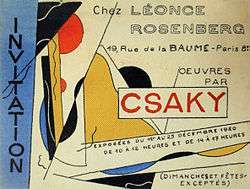

- Joseph Csaky, 1 – 25 December 1920

- Auguste Herbin, 5 – 31 March 1921

- Maîtres du Cubisme: Piet Mondrian, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Georges Braque, Juan Gris, Auguste Herbin, Jean Metzinger, Amédée Ozenfant, Pablo Picasso, Henri Laurens, Joseph Csáky and Gino Severini. May 1921

- Du cubisme à une renaissance plastique: Braque, Gleizes, Gris, Hayden, Herbin, Léger, Metzinger, Mondrian, Ozenfant, Picasso and Valmier, 1922

- Dessins et aquarelles des cubistes: 3 – 25 January 1923

- De Stijl, 1923, 1924

- Jean Metzinger, 17 – 27 June 1925

- Jean Metzinger, 16 April – 10 May 1928

- Francis Picabia, Trente ans de Peinture, 9 – 31 December 1930

- Francis Picabia (drawings), December 1932

Works

%2C_oil_on_canvas%2C_92.4_x_65.1_cm%2C_private_collection.jpg) Jean Metzinger, April 1916, Femme au miroir (Lady at her Dressing Table), oil on canvas, 92.4 x 65.1 cm, private collection

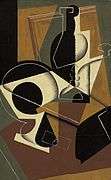

Jean Metzinger, April 1916, Femme au miroir (Lady at her Dressing Table), oil on canvas, 92.4 x 65.1 cm, private collection Juan Gris, 1917, Violon et journal, oil on panel, 92.3 × 60.3 cm. Galerie l'Effort Moderne, no. 5122

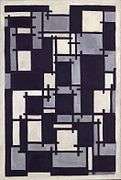

Juan Gris, 1917, Violon et journal, oil on panel, 92.3 × 60.3 cm. Galerie l'Effort Moderne, no. 5122 Theo van Doesburg, 1916, Composition II (Still Life), oil on canvas, 45 x 32 cm. Classique-Baroque-Moderne, Anvers: De Sikkel, Paris 1921: Léonce Rosenberg, [p. 35], as Nature morte.

Theo van Doesburg, 1916, Composition II (Still Life), oil on canvas, 45 x 32 cm. Classique-Baroque-Moderne, Anvers: De Sikkel, Paris 1921: Léonce Rosenberg, [p. 35], as Nature morte. Amedeo Modigliani, 1916, Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, oil on canvas, 81.3 x 54.3 cm. Jacques Lipchitz, Paris, acquired directly from the artist, 1916-c. 1921, by exchange to Léonce Rosenberg, Paris, c. 1921-1922

Amedeo Modigliani, 1916, Jacques and Berthe Lipchitz, oil on canvas, 81.3 x 54.3 cm. Jacques Lipchitz, Paris, acquired directly from the artist, 1916-c. 1921, by exchange to Léonce Rosenberg, Paris, c. 1921-1922%2C_Spanish_-_Still_Life_before_an_Open_Window%2C_Place_Ravignan_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Juan Gris, 1915, Still Life before an Open Window, Place Ravignan, oil on canvas, 115.9 x 88.9 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Formerly owned by Pierre Faure who's large collection of 26 paintings by Gris were purchase from Léonce Rosenberg between 1915 and 1927

Juan Gris, 1915, Still Life before an Open Window, Place Ravignan, oil on canvas, 115.9 x 88.9 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Formerly owned by Pierre Faure who's large collection of 26 paintings by Gris were purchase from Léonce Rosenberg between 1915 and 1927 Juan Gris, 1917, Moulin à café et bouteille, oil on cardboard mounted on panel, 60.8 x 37.7 cm. Provenance: Léonce Rosenberg, Paris

Juan Gris, 1917, Moulin à café et bouteille, oil on cardboard mounted on panel, 60.8 x 37.7 cm. Provenance: Léonce Rosenberg, Paris Joseph Csaky, Deux figures, 1920, relief, limestone, polychrome, 80 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands. Provenance: Léonce Rosenberg, Paris

Joseph Csaky, Deux figures, 1920, relief, limestone, polychrome, 80 cm, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands. Provenance: Léonce Rosenberg, Paris Theo van Doesburg, 1918, Compositie X, oil on canvas, 64 x 43 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris. Theo van Doesburg (1921) Classique-Baroque-Moderne, Anvers: De Sikkel, Paris: Léonce Rosenberg

Theo van Doesburg, 1918, Compositie X, oil on canvas, 64 x 43 cm, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris. Theo van Doesburg (1921) Classique-Baroque-Moderne, Anvers: De Sikkel, Paris: Léonce Rosenberg.jpg) Gino Severini, 1919, Bohémien Jouant de L'Accordéon (The Accordion Player), Museo del Novecento, Milan

Gino Severini, 1919, Bohémien Jouant de L'Accordéon (The Accordion Player), Museo del Novecento, Milan

See also

Notes and references

- Léonce Rosenberg Papers, Correspondence Relating to Cubism in The Museum of Modern Art Archives

- Léonce Rosenberg, Kubisme.info

- Dan Franck, Bohemian Paris: Picasso, Modigliani, Matisse, and the Birth of Modern Art, Grove Press, 2003

- Gino Severini, Futuriste et néoclassique, Musée d'Orsay, Musée de l'Orangerie – Jardin des Tuileries, exhibition catalogue, 2011

- Carton d'invitation à l'exposition Csaky chez Léonce Rosenberg, Galerie l'Effort Moderne (Galerie Léonce Rosenberg), Carton illustré au pochoir, 3 couleurs (printed), 12,5 x 16 cm, 1920, Paris. Source : Kandinsky Library, Centre Georges Pompidou

- Galerie Léonce Rosenberg

- Christopher Green, Cubism and its Enemies, Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1987, pp. 13-47, 215

- Effort Moderne, Galerie L, Paris, Index of Historic Collectors and Dealers of Cubism, 1918-1941, Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Christopher Green, Christian Derouet, Karin von Maur, Whitechapel Art Gallery, Juan Gris: Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 18 September -29 November 1992: Staatsgalerie Stuttgart, 18 December 1992 - 14 February 1993: Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, 6 March - 2 May 1993, Yale University Press, 1992, pp. 6, 22-60

- Thomas J. Watson Library, The Catalog of the Libraries of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries, Vente de biens allemands ayant fait l'objet d'une mesure de Séquestre de Guerre: Collection Uhde. Paris, 30 May 1921

- Malcolm Gee, Dealers, Critics and Collectors of Modern Painting; Aspects of the Parisian Art Market Between 1910 and 1930, Courtauld PhD Dissertation 1977, p. 25

- Bulletin de l'Effort moderne', Léonce Rosenberg, Albert Gleizes, Piet Mondrian, Gino Severini

- Salon de Léonce Rosenberg, the gladiator series

- Peter Brooke, Albert Gleizes, Chronology of his life, 1881–1953

External links

- Jean Metzinger, Léonce Rosenberg, Correspondance échangée entre Léonce Rosenberg et Jean Metzinger, 1916-1936, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Georges Pompidou

- Albert Gleizes, 1930, Sans titre (Untitled), gouache on paper, inscribed: "pour Léonce Rosenberg, très amicalement AG", Rosenberg inventory number: AM 2000-206 (14), Centre Georges Pompidou

- Classique-baroque-moderne, 1921, Theo van Doesburg, Edition De Sikkel, Léonce Rosenberg, éditeur d'art

- Albert Gleizes, 1930-31, oil on canvas, 115 x 90 cm. Commissioned and created to decorate the room of Jacqueline Rosenberg. Musée National d'Art Moderne - Centre Georges Pompidou

- Jean Metzinger, 1929, Untitled, guache and ink on paper, 22 x 15 cm. Livre d'or de Léonce Rosenberg, Musée National d'Art Moderne - Centre Georges Pompidou

- Livre d'or de Léonce Rosenberg, Musée National d'Art Moderne - Centre Georges Pompidou

- Galerie de L'Effort Moderne: black and white photographs. Different views of the gallery from 1913 to 1921, with reproductions and iconographic documents. Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou

- Agence photographique de la réunion des Musées nationaux

See also

- Cubism

- Abstract art

- De Stijl

- Purism

- Modern art