Manifesto of Futurist Musicians

The Manifesto of Futurist Musicians is a manifesto written by Francesco Balilla Pratella on October 11, 1910.[1] It was one of the earliest signs of Futurism's influence in fields outside of the visual arts.[1]

In the manifesto, Pratella appeals to the youth for only they can understand what he says and they are thirsty for 'the new, the actual, the lively.' He goes on to talk about the degeneration of Italian music to that of a vulgar melodrama which he realized through winning a prize for one of his musical Futurist works, La Sina d'Vargoun based on one of Pratella's free verse poems. As part of his monetary prize, he was able to put on a performance of that work, which received mixed reviews. Through his entry into Italian musical society, he was able to experience firsthand the 'intellectual mediocrity' and 'commercial baseness' that makes Italian music inferior to the Futurist evolution of music in other countries.

He then goes on to list composers in other European countries who are making strides in the futurist evolution of music even when battling tradition. For example Pratella discusses the geniuses of Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss and how they struggled to combat and overcome the past with innovatory talent. He expresses his admiration for Edward Elgar in England because he is destroying the past by resisting the will to amplify symphonic forms, and is finding new ways to combine instruments for different effects, which keeps in line with the Futurist aesthetic. Pratella also mentions Finland and Sweden, countries in which innovations are being made by means of nationalism and poeticism, citing the works of Sibelius.

After this list, he raises the question of musical innovation of Italian composers. He states that 'vegetating' schools, conservatories, and academies are likes snares on youths and that the impotency of professors and masters underline traditionalism while stifling efforts to be innovative. Pratella says that this results in the repression of free and daring tendencies, the prostitution of the glories of music's past, and the limitation of a study of forms of a dead culture, among other things.

Pratella then laments the young musical talents who fixate themselves on writing operas under the protection of publishing houses, only to see them fail to have their work realized because the operas are badly written (for lack of a strong ideological and technical foundation) and rarely staged. And the few who do get their works staged only experience ephemeral successes.

Next, Pratella talks about the pure symphony and how it is a refuge for the failed opera composers he previously mentioned, who justify their failures by preaching the death of the music drama. Evoking the double-edged sword, Pratella points out that they confirm the traditional claim that Italian composers are inept at the symphonic form, the most noble and vital form of composition. And it is only the writer's own impotence to blame for this double failure. He then scolds them for writing "well-made music," or music that appeals to the population, and scolds the public for letting itself be cheated by its own free will.

The author moves on to the topic of commercialism and the power of publisher-merchants, claiming that they impose limitations on operatic forms and proclaim the models that cannot be surpassed (the 'vulgar' operas of Giacomo Puccini and Umberto Giordano). He also points out how publishers have the power of controlling public tastes, harboring a sense of the Italian monopoly on melody and bel canto.

Pratella then praises one Italian composer and a publisher's favorite, Pietro Mascagni, for his will to rebel against the traditions of art, the publishers, and the public. To the author, Mascagni has shown great talent in his attempts at innovation in the harmonic and lyrical aspects of opera.

The Futurist Manifesto is evoked towards the end of Pratella's manifesto, as he reiterates Futurism's pursuit of the rebellion of the life of intuition and feeling and the exaltation of the past at the expense of the future. He calls for the young composers to have the 'hearts to live and fight, minds to conceive, and brows free of cowardice.' Pratella then frees himself from the 'chains of tradition, doubt, opportunism, and vanity.'

Pratella offers his conclusions to the 'young, bold and the restless' while repudiating the title of Maestro as a stigma of mediocrity and ignorance:

- To convince young composers to desert schools, conservatories and musical academies, and to consider free study as the only means of regeneration.

- To combat the venal and ignorant critics with assiduous contempt, liberating the public from the pernicious effects of their writings.

- To found with this aim in view a musical review that will be independent and resolutely opposed to the criteria of conservatory professors and to those of the debased public.

- To abstain from participating in any competition with the customary closed envelopes and related admission charges, denouncing all mystifications publicly, and unmasking the incompetence of juries, which are generally composed of fools and impotents.

- To keep at a distance from commercial or academic circles, despising them, and preferring a modest life to bountiful earnings acquired by selling art.

- The liberation of individual musical sensibility from all imitation or influence of the past, feeling and singing with the spirit open to the future, drawing inspiration and aesthetics from nature, through all the human and extra-human phenomena present in it. Exalting the man-symbol everlastingly renewed by the varied aspects of modern life and its infinity of intimate relationships with nature.

- To destroy the prejudice for “well-made” music—rhetoric and impotence—to proclaim the unique concept of Futurist music, as absolutely different from music to date, and so to shape in Italy a Futurist musical taste, destroying doctrinaire, academic and soporific values, declaring the phrase “let us return to the old masters” to be hateful, stupid and vile.

- To proclaim that the reign of the singer must end, and that the importance of the singer in relation to a work of art is the equivalent of the importance of an instrument in the orchestra.

- To transform the title and value of the “operatic libretto” into the title and value of “dramatic or tragic poem for music”, substituting free verse for metric structure. Every opera writer must absolutely and necessarily be the author of his own poem.

- To combat categorically all historical reconstructions and traditional stage sets and to declare the stupidity of the contempt felt for contemporary dress.

- To combat the type of ballad written by Tosti and Costa, nauseating Neapolitan songs and sacred music which, having no longer any reason to exist, given the breakdown of faith, has become the exclusive monopoly of impotent conservatory directors and a few incomplete priests.

- To provoke in the public an ever-growing hostility towards the exhumation of old works which prevents the appearance of innovators, to encourage the support and exaltation of everything in music that appears original and revolutionary, and to consider as an honor the insults and ironies of moribunds and opportunists.

Other writings

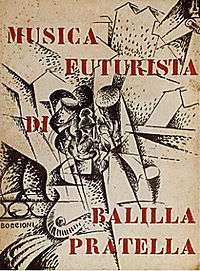

Pratella authored two more manifestos, the "Technical Manifesto of Futurist Music" and "The Destruction of Quadrature." These manifestos along with "Manifesto for Futurist Musicians" were published together in 1912. This volume also contained Pratella's Futurist Music for Orchestra. [1]

See also

- The Art of Noises

- Musica Futurista: The Art of Noises

- Intonarumori

- Noise music

- Experimental music

External links

References

- Tisdall, Caroline, Futurist Music 1910-1920: Luigi Russolo and Francesco Balila Pratella, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-12-18. Retrieved 2008-12-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)