Anagrelide

Anagrelide (Agrylin/Xagrid, Shire and Thromboreductin, AOP Orphan Pharmaceuticals AG) is a drug used for the treatment of essential thrombocytosis (also known as essential thrombocythemia), or overproduction of blood platelets. It also has been used in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Agrylin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601020 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, partially through CYP1A2 |

| Elimination half-life | 1.3 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (<1%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

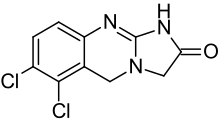

| Formula | C10H7Cl2N3O |

| Molar mass | 256.09 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Anagrelide controlled release (GALE-401) is in phase III clinical trials by Galena Biopharma for the treatment of essential thrombocytosis.[2]

Medical uses

Anagrelide is used to treat essential thrombocytosis, especially when the current treatment of the patient is insufficient.[3] Essential thrombocytosis patients who are suitable for anagrelide often meet one or more of the following factors:[4][5]

- age over 60 years

- platelet count over 1000×109/L

- a history of thrombosis

According to a 2005 Medical Research Council randomized trial, the combination of hydroxyurea with aspirin is superior to the combination of anagrelide and aspirin for the initial management of essential thrombocytosis. The hydroxyurea arm had a lower likelihood of myelofibrosis, arterial thrombosis, and bleeding, but it had a slightly higher rate of venous thrombosis.[3] Anagrelide can be useful in times when hydroxyurea proves ineffective.

Side-effects

Common side effects are headache, diarrhea, unusual weakness/fatigue, hair loss, nausea.

The same MRC trial mentioned above also analyzed the effects of anagrelide on bone marrow fibrosis, a common feature in patients with myelofibrosis. The use of anagrelide was associated with a rapid increase in the degree of reticulin deposition (the mechanism by which fibrosis occurs), when compared to those in whom hydroxyurea was used. Patients with myeloproliferative conditions are known to have a very slow and somewhat variable course of marrow fibrosis increase. This trend may be accelerated by anagrelide. This increase in fibrosis appeared to be linked to a drop in hemoglobin as it progressed. Stopping anagrelide (and switching patients to hydroxyurea) appeared to reverse the degree of marrow fibrosis. Thus, patients on anagrelide may need to be monitored on a periodic basis for marrow reticulin scores, especially if anemia develops, or becomes more pronounced if present initially.[6]

Less common side effects include: congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, cardiomegaly, complete heart block, atrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular accident, pericarditis, pulmonary infiltrates, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension, pancreatitis, gastric/duodenal ulceration, renal impairment/failure and seizure.

Due to these issues, anagrelide should not generally be considered for first line therapy for essential thrombocytosis.

Mechanism of action

Anagrelide works by inhibiting the maturation of platelets from megakaryocytes.[7] The exact mechanism of action is unclear, although it is known to be a phosphodiesterase inhibitor.[8] It is a potent (IC50 = 36nM) inhibitor of phosphodiesterase-II. It inhibits PDE-3 and phospholipase A2.[9]

Synthesis

Phosphodiesterase inhibitor with antiplatelet activity.

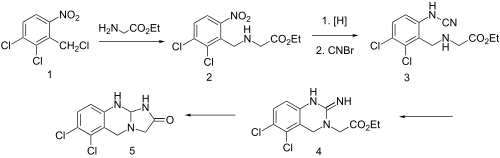

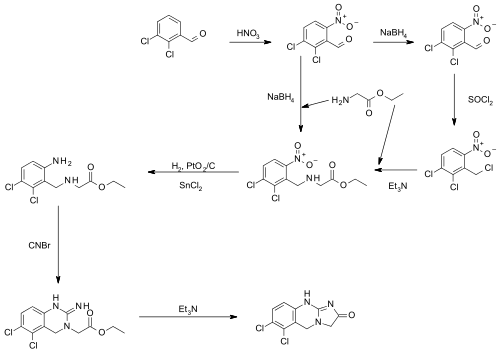

| Synthesis 1[10][11] | Synthesis 2 |

|---|---|

|  |

Condensation of benzyl chloride 1 with ethyl ester of glycine gives alkylated product 2. Reduction of the nitro group leads to the aniline and reaction of this with cyanogen bromide possibly gives cyanamide 3 as the initial intermediate. Addition of the aliphatic would then lead to formation of the quinazoline ring (4). Amide formation between the newly formed imide and the ester would then serve to form the imidazolone ring, whatever the details of the sequence, there is obtained anagrelide (5).

References

- Voglová J, Maisnar V, Beránek M, Chrobák L (2006). "[Combination of imatinib and anagrelide in treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia in blastic phase]". Vnitr̆ní Lékar̆ství (in Czech). 52 (9): 819–22. PMID 17091608.

- Inc., Galena Biopharma (2016-12-28). "Galena Biopharma Confirms Regulatory Pathway for GALE-401 (Anagrelide Controlled Release)". globenewswire.com.

- Harrison CN, Campbell PJ, Buck G, et al. (July 2005). "Hydroxyurea compared with anagrelide in high-risk essential thrombocythemia". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (1): 33–45. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043800. PMID 16000354.

- Reilly, John T. (1 February 2009). "Anagrelide for the treatment of essential thrombocythemia: a survey among European hematologists/oncologists". Hematology. 14 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1179/102453309X385115. PMID 19154658.

- Brière, Jean B (1 January 2007). "Essential thrombocythemia". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2 (1): 3. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-3. PMC 1781427. PMID 17210076.

- Campbell PJ, Bareford D, Erber WN, et al. (June 2009). "Reticulin accumulation in essential thrombocythemia: prognostic significance and relationship to therapy". J. Clin. Oncol. 27 (18): 2991–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3174. PMC 3398138. PMID 19364963.

- Petrides PE (2006). "Anagrelide: what was new in 2004 and 2005?". Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 32 (4 Pt 2): 399–408. doi:10.1055/s-2006-942760. PMID 16810615.

- Jones GH, Venuti MC, Alvarez R, Bruno JJ, Berks AH, Prince A (February 1987). "Inhibitors of cyclic AMP phosphodiesterase. 1. Analogues of cilostamide and anagrelide". J. Med. Chem. 30 (2): 295–303. doi:10.1021/jm00385a011. PMID 3027338.

- Harrison CN, Bareford D, Butt N, et al. (May 2010). "Guideline for investigation and management of adults and children presenting with a thrombocytosis". Br. J. Haematol. 149 (3): 352–75. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08122.x. PMID 20331456.

- W. N. Beverung, A. Partyka, U.S. Patent 3,932,407; USRE 31617; T. A. Jenks et al., U.S. Patent 4,146,718 (1976, 1984, 1979 all to Bristol-Myers).

- Yamaguchi, Hitoshi; Ishikawa, Fumiyoshi (1981). "Synthesis and reactions of 2-chloro-3,4-dihydrothienopyrimidines and -quinazolines". Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 18: 67–70. doi:10.1002/jhet.5570180114.