Bristol Myers Squibb

Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) is an American pharmaceutical company, headquartered in New York City.[2]

A Bristol Myers Squibb R&D facility in Lawrence, New Jersey | |

| Public | |

| Traded as | NYSE: BMY S&P 100 component S&P 500 component |

| ISIN | US1101221083 |

| Industry | Pharmaceuticals |

| Founded | 1887 |

| Founder | William McLaren Bristol John Ripley Myers E. R. Squibb |

| Headquarters | 430 East 29th Street New York City, New York, United States |

Key people | Giovanni Caforio, M.D. (Chairman & CEO) Charles Bancroft (CFO) |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | ~23,300 (2018) |

| Website | BMS.com |

| Footnotes / references [1] | |

Bristol Myers Squibb manufactures prescription pharmaceuticals and biologics in several therapeutic areas, including cancer, HIV/AIDS, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hepatitis, rheumatoid arthritis and psychiatric disorders.

BMS' primary R&D sites are located in Lawrence, New Jersey (formerly Squibb, near Princeton), New Brunswick, New Jersey, and Redwood City, California; with other sites in Devens and Cambridge, Massachusetts, East Syracuse, New York, Braine-l'Alleud, Belgium, Tokyo, Japan, Bangalore, India and Wirral, United Kingdom.[3][4] BMS previously had an R&D site in Wallingford, Connecticut (formerly Bristol-Myers).[5]

History

Squibb

The Squibb corporation was founded in 1858 by Edward Robinson Squibb in Brooklyn, New York.[6][7] Squibb was known as an advocate of quality control and high purity standards early within the pharmaceutical industry.[8] He went on to self-publish an alternative to the U.S. Pharmacopeia titled Squibb's Ephemeris of Materia Medica, after failing to convince the American Medical Association to incorporate higher purity standards.[9] Materia Medica, Squibb products, and Edward Squibb's opinion on the fundamentals of pharmacy are found in many medical papers of the late 1800s.[10][11][12][13] The American Journal of Pharmacy published more than one hundred papers of Squibb's research surrounding the industry.[14]

Squibb Corporation served as a major supplier of medical goods to the Union Army during the American Civil War, providing portable medical kits containing morphine, surgical anesthetics, and quinine for the treatment of malaria (which was endemic in most of the eastern United States at that time).[15][16]

In 1944, Squibb opened the world's largest penicillin plant in New Brunswick, New Jersey.[17]

Bristol-Myers

.jpg)

In 1887, Hamilton College graduates William McLaren Bristol and John Ripley Myers purchased the Clinton Pharmaceutical company of Clinton, New York.[18] In May of 1898, they decided to rename it Bristol, Myers and Company.[18] Following Myers' death in 1899, Bristol changed the name to the Bristol-Myers Corporation.[18] During the 1890s, the company introduced its first nationally recognized product Sal Hepatica, a laxative mineral salt, followed by Ipana toothpaste in 1901.[19][20] Other divisions were Clairol (hair colors and haircare) and Drackett (household products such as Windex and Drano).[21]

In 1943, Bristol-Myers acquired Cheplin Biological Laboratories, a producer of acidophilus milk in East Syracuse, New York,[22] and converted the plant to produce penicillin for the World War II Allied forces.[23] After the war, the company renamed the plant Bristol Laboratories in 1945 and entered the civilian antibiotics market, where it faced competition from Squibb.[19] Penicillin production at the East Syracuse plant ended in 2005, when it became less expensive to produce overseas.[24][25] As of 2010, the facility was used for the manufacturing process development and production of other biologic medicines for clinical trials and commercial use.[26][27]

Merger

In 1989, Bristol-Myers and Squibb merged and became Bristol-Myers Squibb.[28]

In 1999, then U.S. President Bill Clinton awarded Bristol-Myers Squibb the National Medal of Technology, the nation's highest recognition for technological achievement, "for extending and enhancing human life through innovative pharmaceutical research and development and for redefining the science of clinical study through groundbreaking and hugely complex clinical trials that are recognized models in the industry."[29]

2000 to 2010

In 2002, the company was involved in a lawsuit of illegally maintaining a monopoly on Taxol, its cancer treatment, and it was again sued for the antitrust lawsuit 5 years later, which cost the company $125 million for settlement.[30]

Also in 2002, Bristol-Myers Squibb was involved in an accounting scandal that resulted in a significant restatement of revenues from 1999 to 2001.[31] The restatement was the result of an improper booking of sales related to "channel stuffing" as the practice of offering excess inventory to customers to create higher sales numbers.[31] The company has since settled with the United States Department of Justice and Securities and Exchange Commission, agreeing to pay $150 million while neither admitting nor denying guilt.[32]

On October 24, 2002, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. restated earnings downward for parts of 2000 and 2001 while revising this year's earnings upward because of its massive inventory backlog imbroglio that spurred two government investigations.[33] On March 15, 2004, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co. adjusted upward its fourth-quarter and full-year 2003 results after reversing an earlier decision about how to deal with accounting errors made in prior years.[34] As part of a Deferred Prosecution Agreement, the company was placed under the oversight of a monitor appointed by the U.S. Attorney in New Jersey. In addition, the former head of the Pharma group, Richard Lane, and the ex-CFO, Fred Schiff, were indicted for federal securities violations.[35]

In July 2006, an investigation of the company was made public, and the FBI raided the company's corporate offices.[36] The investigation centered on the distribution of Plavix and charges of collusion.[36][37] On September 12, 2006, the monitor, former Federal Judge Frederick B. Lacey, urged the company to remove then CEO Peter Dolan over the Plavix dispute. Later that day, BMS announced that Dolan would indeed step down.[38]

The Deferred Prosecution Agreement expired in June 2007 and the Department of Justice did not take any further legal action against the company for matters covered by the DPA. Under CEO Jim Cornelius, who was CEO following Dolan until May 2010, all executives involved in the "channel-stuffing" and generic competition scandals have since left the company.

In 2009, the company began a major restructuring focusing on the pharmaceutical business and biologic products, along with productivity initiatives and cost-cutting and streamlining business operations through a multi-year program of on-going layoffs. This was part of a business strategy launched in 2007 to transform the company from a large diversified pharmaceutical company to a specialty biopharma company, which also included the closure of half of their manufacturing facilities.[39]:19 As another cost-cutting measure, Bristol-Myers Squibb also reduced health-care subsidies for retirees and plans to freeze their pension plan at the end of 2009.[40][41]

BMS is a Fortune 500 Company (#114 in 2010 list). Newsweek's 2009 Green Ranking recognized Bristol-Myers Squibb as 8th among 500 of the largest United States corporations. Also, BMS was included in the 2009 Dow Jones Sustainability North America Index of leading sustainability-driven companies.

Lamberto Andreotti was named CEO in 2010; he had previously served as "president and COO responsible for all pharmaceutical operations worldwide."[42]

2010 onward

In 2010, Lou Schmukler joined Bristol-Myers Squibb as the president of global product development and design.[39][43] Schmukler led the team that completed the company's strategic transformation to a specialty biopharmaceutical company that had begun in 2007.[39] As of 2011, the company had a dozen manufacturing facilities and six product development sites.[39]

Citing major developments and a market capitalization of US$87 billion and stock appreciation of 61.4%, Bristol-Myers Squibb was ranked as the best drug company of 2013 by Forbes magazine.[44]

In December 2014 the company received FDA approval for the use of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab (Opdivo) in treating patients whose skin cancer cannot be removed or have not responded to previous drug therapies.[45] In February 2015, the company initiated a research partnership with Rigel Pharmaceuticals which could generate more than $339 million. In March, the company obtained an exclusive opportunity to both licence and commercialise PROSTVAC, Bavarian Nordic's phase III prostate specific antigen targeting cancer immunotherapy. Bavarian Nordic would receive an upfront payment of $60 million as well as incremental payments up to $230 million, if the overall survival of test patients exceeds that seen in Phase II tests. Bavarian could also receive milestone payments of between $110 million and $495 million, dependent on regulatory authorization, and these payments have the potential to total up to $975 million.[46]

In May 2015, Dr. Giovanni Caforio became CEO of the company;[47] Caforio was formerly the company's COO and succeeded Andreotti upon his retirement.[42] Andreotti subsequently succeeded James Cornelius as executive chairman upon his retirement.[42]

In late February 2017, the Wall Street Journal and Fortune, among others, reported that activist investor, Carl Icahn, had taken a stake in the company, signalling a potential future takeover[48][49] from the likes of Gilead Sciences.[50]

In April 2018, the company reported net income of $1.5 billion, or 91 cents per share, for the first quarter of the year, thanks to the increased sales of their cancer drug Opdivo.[51]

Corporate acquisitions and divestments as Bristol Myers Squibb

In August 2009, during a major restructuring activity, BMS acquired the biotechnology firm Medarex as part of the company's "String of Pearls" strategy of alliances, partnerships and acquisitions.[52] In November 2009, Bristol Myers Squibb announced that it was "splitting off" Mead Johnson Nutrition by offering BMY shareholders the opportunity to exchange their stock for shares in Mead Johnson.[53] According to Bristol Myers Squibb, this move was expected to further sharpen the company's focus on biopharmaceuticals.[53]

In October 2010, the company acquired ZymoGenetics, securing an existing product as well as pipeline assets in hepatitis C, cancer and other therapeutic areas.

Bristol Myers Squibb agreed to pay around $2.5 billion in cash to buy Inhibitex Inc. in attempt to compete with Gilead/Pharmasset to produce Hepatitis C drugs. The settlement will be finished in 2 months for its Inhibitex's shareholders acceptance of 126 percent premium price of its price over the previous 20 trading days ended on January 6.[54] On June 29, Bristol-Myers Squibb extended its portfolio of diabetes treatments when it agreed to buy Amylin Pharmaceuticals for around US$5.3 billion in cash and pay US$1.7 billion to Eli Lilly to cover Amylin's debt and its outstanding collaboration-related obligations.[55] AstraZeneca, who already collaborated on several diabetes treatments with Bristol-Myers Squibb, agreed to pay US$3.4 billion in cash for the right to continue development of Amylin's products.[55] Two years later, in 2014, the company divested Amylin to AstraZeneca.[39]:19

In April 2014, BMS announced its acquisition of iPierian for up to $725 million.[56]

In February 2015, the company acquired Flexus Biosciences for $1.25 billion. As part of this deal, BMS will gain full rights to Flexus' lead small molecule IDO1-inhibitor, F001287.[57] In November, the company acquired the cardiovascular disease drug developer Cardioxyl for up to $2.075 billion. The deal strengthens the BMS' critical pipelines with the phase II candidate for acute decompensated heart failure, CXL-1427.[58]

In March 2016, the company announced it would acquire Padlock Therapeutics for up to $600 million.[59] In early July, the company announced it would acquire Cormorant Pharmaceuticals for $520 million, boosting BMS' oncology offering through Cormorants monoclonal antibody targeted against interleukin-8.[60]

In August 2017 the company acquired IFM Therapeutics for $300 million upfront, with contingency payments of $1.01 billion due on certain milestones – allowing BMS to better compete against Merck & Co's cancer rival treatment, Keytruda.[61]

In early January 2019, the company announced it would acquire Celgene (NASDAQ:CELG) for $74 billion ($95 billion including debt[62]), in a deal that would become the largest pharmaceutical-company acquisition ever.[63] The Celgene acquisition aimed to be a refresher to the company's pipeline, helping to overcome from declining sales of Opdivo relative to competitor Keytruda.[64] Under the terms of the deal, Celgene shareholders would receive one BMS share as well as $50 in cash for each Celgene share held, valuing Celgene at $102.43 a share; representing a 54% premium to the previous days closing price.[65] Investor opposition to this acquisition, leading into an April 12 shareholder vote, appeared when BMS's second-largest investor, Wellington Management, voiced its opposition, followed by investor Starboard Value.[64] In April 2019 BMS announced that 75% of its shareholders voted to approve the pending merger with Celgene. Transaction to close in the third quarter of 2019, subject to regulatory approvals.[66] Newly issued BMS shares and CVRs will commence trading on the New York Stock Exchange, with the CVRs trading under the symbol ‘BMYRT'.[67]

The strategic divestment of the company's consumer health business, UPSA, to Taisho completed in 2019.[68] UPSA focused product delivery on France and the rest of Europe. As early as 2005, the company had divested individual consumer products,[69][70] and its US- and Canada-focused consumer products business.[71]

In August the Amgen announced it would acquire the Otezla drug programme from Celgene for $13.4 billion, as part of Celgene and Bristol Myers Squibb's merger deal.[72][73]

In February 2020, Bristol Myers Squibb and partner Biomotiv launched a new company called Anteros Pharmaceuticals, which focuses on creating inflammation and fibrosis medicines. [74]

Tree of mergers and acquisitions

The following is an illustration of the company's major mergers and acquisitions and historical predecessors:

- Bristol-Myers Squibb (Formed by the merger of Squibb Corporation (Est 1858) and Bristol-Myers (Est 1887))

- Adnexus Therapeutics

- ConvaTec

- Kosan Biosciences

- Medarex (Acq 2009)

- ZymoGenetics (Acq 2010)

- Amira Pharmaceuticals

- Inhibitex Inc (Acq 2012)

- Amylin Pharmaceuticals (Acq 2012 jointly with AstraZeneca)

- iPierian (Acq 2014)

- Flexus Biosciences (Acq 2015)

- Cardioxyl (Acq 2015)

- Padlock Therapeutics (Acq 2016)

- Cormorant Pharmaceuticals (Acq 2016)

- IFM Therapeutics (Acq 2017)

- Celgene (Acq 2019)

- Signal Pharmaceuticals, Inc (Acq 2000)

- Anthrogenesis (Acq 2002)

- Pharmion Corporation (Acq 2008)

- Gloucester Pharmaceuticals (Acq 2009)

- Abraxis BioScience Inc (Acq 2010)

- Avila Therapeutics, Inc (Acq 2012)

- Quanticel (Acq 2015)

- Receptos (Acq 2015)

- EngMab AG (Acq 2016)

- Delinia (Acq 2017)

- Impact Biomedicines (Acq 2018)

- Juno Therapeutics (Acq 2018)

- AbVitro (Acq 2016)

- RedoxTherapies (Acq 2016)

- Celegene (Acq 2020)

Finances

For the fiscal year 2017, Bristol Myers Squibb reported earnings of US$1.007 billion, with an annual revenue of US$20.776 billion, an increase of 6.9% over the previous fiscal cycle. Bristol-Myers Squibb's shares traded at over $55 per share, and its market capitalization was valued at over US$81.6 billion in October 2018.[75] In 2018, 85% of the company's revenues came from just five products.[76] In 2018, Bristol-Myers Squibb spent 36% of its total revenue on R&D expenses.[77] Bristol-Myers Squibb ranked 145th on the Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by revenue in 2018.[78]

| Year | Revenue in mil. USD$ |

Net income in mil. USD$ |

Total assets in mil. USD$ |

Price per share in USD$ |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 18,605 | 3,000 | 28,138 | 14.60 | |

| 2006 | 16,208 | 1,585 | 25,575 | 15.24 | |

| 2007 | 15,617 | 2,165 | 25,926 | 18.98 | |

| 2008 | 17,715 | 5,247 | 29,486 | 14.95 | |

| 2009 | 18,808 | 10,594 | 31,008 | 15.90 | |

| 2010 | 19,484 | 3,090 | 31,076 | 19.76 | |

| 2011 | 21,244 | 3,701 | 32,970 | 23.41 | |

| 2012 | 17,621 | 1,959 | 35,897 | 28.04 | |

| 2013 | 16,385 | 2,563 | 38,592 | 38.39 | 28,000 |

| 2014 | 15,879 | 2,004 | 33,749 | 47.03 | 25,000 |

| 2015 | 16,560 | 1,565 | 31,748 | 59.63 | 25,000 |

| 2016 | 19,427 | 4,457 | 33,707 | 59.73 | 25,000 |

| 2017 | 20,776 | 1,007 | 33,551 | 55.88 | 23,700 |

| 2018 | 22,561 | 4,920 | 34,986 | 51.98 | 23,300 |

Pharmaceuticals

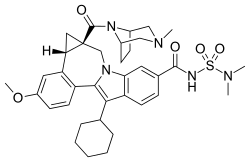

.jpg)

The following is a list of key pharmaceutical products:[79]

Cardiovascular diseases

- Avalide (irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide) – comarketed with Sanofi

- Avapro (irbesartan) – comarketed with Sanofi

- Coumadin (warfarin)

- Eliquis (apixaban) – comarketed with Pfizer

- Plavix (clopidogrel) – comarketed with Sanofi

- Pravachol (pravastatin)

Diabetes mellitus

- Bydureon (exenatide extended-release) – marketed by BMS only in some countries

- Byetta (exenatide) – marketed by BMS only in some countries, such as Russian Federation

- Farxiga/Forxiga (dapagliflozin)

- Glucophage (metformin) – marketed by BMS only in USA

- Glucophage XR (metformin extended release) – marketed by BMS only in USA

- Glucovance (Glyburide/metformin) – marketed by BMS only in USA

- Kombiglyze XR/Komboglyze (saxagliptin/metformin extended release) – comarketed with AstraZeneca

- Onglyza (saxagliptin) – comarketed with AstraZeneca

Infectious diseases, including HIV infection and associated conditions

- Atripla (efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) – comarketed with Gilead Sciences

- Azactam (aztreonam)

- Baraclude (entecavir)

- Daklinza (daclatasvir)

- Evotaz (atazanavir/cobicistat)

- Megace (megestrol acetate)

- Reyataz (atazanavir)

- Sustiva/Stocrin (efavirenz)

- Videx (didanosine)

- Videx EC (didanosine delayed-release)

- Zerit (stavudine)

Inflammatory disorders

- Kenalog-10 (triamcinolone acetonide)

- Kenalog-40 (triamcinolone acetonide)

Oncology

- BiCNU (carmustine)

- CeeNU (lomustine)

- Droxia/Hydrea (hydroxycarbamide)

- Empliciti (Elotuzumab)

- Erbitux (cetuximab)

- Etopophos (etoposide)

- Ixempra (ixabepilone)

- Lysodren (mitotane)

- Megace (megestrol acetate)

- Opdivo (nivolumab) is a programmed death receptor blocking antibody used for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic melanoma and metastatic squamous non-small-cell lung carcinoma. In contrast to traditional chemotherapies and targeted anti-cancer therapies, which exert their effects by direct cytotoxic or tumor growth inhibition, nivolumab acts by inducing the immune system to attack the tumor.[80]

- Sprycel (dasatinib)

- Taxol (paclitaxel). At one time, BMS held the solitary contract to harvest the bark of endangered yew trees on United States territory for the manufacture of chemotherapy drug paclitaxel (Taxol). Current paclitaxel production comes from renewable sources. BMS also held the original paclitaxel license, but there are now multiple generic producers.[81]

- Vumon (teniposide)

- Yervoy (ipilimumab)

Psychiatry

- Abilify (aripiprazole comarketed with Otsuka Pharmaceutical)

Rheumatic disorders

- Orencia (abatacept)

Transplant rejection

- Nulojix (belatacept)

Out of production

Products under development

The following is a selective list of investigational products under development, as of 2015:[82]

- Beclabuvir (BMS-791325) – phase III

- BMS-906024 – phase I

- BMS-955176 – phase II

- Brivanib alaninate (BMS-582664) – development terminated

- Elotuzumab (BMS-901608) – phase III

- Fostemsavir (BMS-663068) – phase III

- Lirilumab (BMS-986015)

- Lulizumab pegol (BMS-931699) – phase II

Scandals

Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johns Hopkins University and the Rockefeller Foundation are currently the subject of a $1 billion lawsuit from Guatemala for "roles in a 1940s U.S. government experiment that infected hundreds of Guatemalans with syphilis".[83] A previous suit against the United States government was dismissed in 2011 for the Guatemala syphilis experiments when a judge determined that the U.S. government could not be held liable for actions committed outside of the U.S.[84]

Notes and references

- "US SEC: Form 10-K Bristol-Myers Squibb Company". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb - Contact Us". 18 March 2020.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb and Biocon's Syngene open new R&D Facility at Biocon Park" (Press release). Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- https://www.bms.com/about-us/our-company/worldwide-facilities/our-research-facilities.html

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb to lay off 149 as Wallingford, Connecticut, site nears closure". Fiercepharma.com. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Gray, Christopher (30 August 2012). "Still in Fashion, a Century Later". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Kumar, B. (14 November 2012). Mega Mergers and Acquisitions: Case Studies from Key Industries. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-00590-8.

- The National Druggist. 1905.

- "E. R. Squibb | American chemist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Hollopeter, W.C. (8 January 1885). "Inverse Type of Temperature in Typhoid Fever, with a Report of Two Cases — Temperature Peculiarities in Epidemics, with a Report of Seven Cases in One Family". Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 112: 28–32. doi:10.1056/NEJM188308301090903. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

The writer noticed (in December, 1882) the important fact that when common or Japan camphor and crystallized carbolic acid are mixed together and subjected to heat, a colorless liquid would be the result. The only reference he finds so far with regard to this reaction occurs in the very excellent and valuable scientific publication of Dr. E. R. Squibb, " Ephemeris of Materia Medica", etc., on page 673, vol. ii., No. 5, where a brief allusion appears under the appellation of Compound Alum Powder. Dr. F. R. Squibb, however, in a letter to the writer states that he has " several times before heard of this reaction between phenol and camphor.

- Worthen, Dennis (2003). "Edward Robinson Squibb (1819–1900): Advocate of Product Standards". Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 46 (6): 754–758. doi:10.1331/1544-3191.46.6.754.Worthen. PMID 17176693. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- Blake, J.B. (1899). "Administration of Ether at the Boston City Hospital". Boston Med Surg J. 141 (13): 312–314. doi:10.1056/NEJM189909281411303.

Until within six months Squibb's other has been exclusively used at the Boston City Hospital. Recently .MeliiHTéift's ether has been tried, ¡uni has given fair satisfaction ; Squibb's is still preferred by most of the house officers.

- Brown, W.S. (1885). "Forty Year's Experience in Midwifery". Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 112 (11): 241. doi:10.1056/nejm188503121121101.

One reason why ergot has fallen into disrepute is the poor quality of many specimens offered for sale. Dr. Squibb's aqueous extract rarely disappoints me.

- Capace, Nancy (1 January 2001). Encyclopedia of Delaware. Somerset Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-403-09612-1.

- Smith (2001). Medicines for the Union Army: the United States Army laboratories during the Civil War. Pharmaceutical Products Press. Accessed 2014-11-25.

- Navy Medicine. Naval Medical Command. 2005.

- Rosenbloom, Bert (25 July 2012). Marketing Channels (in German). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-133-70757-8.

- Cox, Jim (18 September 2008). Sold on Radio: Advertisers in the Golden Age of Broadcasting. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5176-0.

- Bert Rosenbloom, Marketing Channels, Bristol-Myers Squibb, 2011, page 609

- "Ipana toothpaste tasted success in early 1900s". Loveland Reporter-Herald. 20 April 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Salpukas, Agis (16 August 1984). "BUSINESS PEOPLE; 3 Executive Changes Set by Bristol-Myers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Botti, Timothy J. (2006). Envy of the World: A History of the U.S. Economy & Big Business. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-432-7.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb marks completion of East Syracuse plant's transformation". syracuse. 13 September 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb: Big Pharma's small wonder". Fortune. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Harris, Gardiner (19 January 2009). "Drug Making's Move Abroad Stirs Concerns". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- "At Bristol-Myers Squibb plant in East Syracuse, old buildings will make way for new drugs". syracuse. 30 June 2010. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Bristol Myers Squibb East Syracuse Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Facility - Pharmaceutical Technology". www.pharmaceutical-technology.com. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Bristol-Myers, Squibb Agree to Merge : $12-Billion Stock Swap Would Form 2nd-Largest Drug Firm". Los Angeles Times. 28 July 1989. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- "NSTMF". NSTMF. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- "Bristol hit with antitrust suit". CNN. 4 June 2002. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- Chopra, Prem (2009). Masters of the Game. Brook of Life. ISBN 978-0-9786321-3-7.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb Company : Lit. Rel. No. 18822" (Press release). US Securities and Exchange Commission. 6 August 2004. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

Bristol-Myers inflated its results primarily by: (1) stuffing its distribution channels with excess inventory near the end of every quarter in amounts sufficient to meet sales and earnings targets set by officers ("channel-stuffing")

- "Bristol-Myers to restate earnings as third quarter profits plunge". Archived from the original on 5 November 2013.

- "Bristol-Myers restates results upward due to accounting errors". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- Saul, Stephanie (15 June 2005). "2 Former Bristol-Myers Executives Charged With Fraud". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "Former Bristol-Myers Squibb Senior Executive Pleads Guilty for Role in Dishonest Dealings with the Federal Government". FBI. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Business Report Archived 17 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, July 31, 2006. Retrieved September 7, 2006. Archived at

- CNN.com, September 12, 2006. Retrieved September 12, 2006

- Wright, Rob (October 2018). "From Big to Specialty—The Operational Transformation of Bristol-Myers Squibb". Life Science Leader. 10 (10). Erie, Pennsylvania: VertMarkets. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb Announces Pension Risk Transfer | PLANSPONSOR". www.plansponsor.com. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb Closes US Retirement Plan | Chief Investment Officer". www.ai-cio.com. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Staff (15 February 2015). "BMS CEO Andreotti to Retire; COO named as Successor". Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News (paper). 35 (4). p. 6.

- "A Primer On Biopharma Manufacturing From Bristol-Myers Squibb's Lou Schmukler". www.lifescienceleader.com. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- Herper, Matthew (31 December 2013). "Grading Pharma in 2013". Forbes.

- Anna Edney (22 December 2014). "Bristol-Myers Drug Wins U.S. Approval to Treat Advanced Melanoma". Bloomberg.

- "Bavarian Nordic Could Tally up to $975 Million in Prostate Cancer Deal with BMS – GEN News Highlights – GEN". GEN.

- Johnson, Linda A. "New CEO Takes Over Evolving Drugmaker Bristol-Myers Squibb". ABC News. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb Shares Just Spiked on Reports of a Carl Icahn Stake". Fortune. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- Benoit, David; Rockoff, Jonathan D. (22 February 2017). "Carl Icahn Takes Stake in Bristol-Myers Squibb". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- "Making (good) deals is hard to do, Gilead CEO says, but he's working on it – FiercePharma". fiercepharma.com. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- LaVito, Angelica (26 April 2018). "Bristol-Myers' cancer drug Opdivo fuels growth, but revenue falls short". CNBC. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- https://finance.yahoo.com/news/BristolMyers-Squibb-to-bw-571310065.html?x=0&.v=1%5B%5D

- Woelfel, Joseph. "Bristol-Myers to Split Off Mead Johnson". TheStreet. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "Bristol Buys Inhibitex for $2.5 Billion to Compete in Hepatitis". 8 January 2012.

- Gershberg, Michele (30 June 2012). "Bristol-Myers to buy Amylin for about USD 5.3 billion". Reuters.

- "Bristol-Myers to buy iPierian". Genetic Engineering & biotechnology news. 29 April 2014.

- "GEN – News Highlights:BMS Deals Add to its Immuno-Oncology Portfolio". GEN.

- "BMS to Buy Cardioxyl for Up to $2.075B". GEN.

- "BMS to Acquire Padlock Therapeutics for Up to $600M". GEN.

- "BMS Snags Cormorant Pharmaceuticals for Up to $520M (online title: BMS Acquires Cormorant Pharmaceuticals for Up to $520M)". News: Industry Watch (online: GEN News Highlights). Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. 36 (14): 10. August 2016.

- Editorial, Reuters. "Bristol-Myers to buy IFM Therapeutics to strengthen cancer pipeline".

- https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-celgene-m-a-bristol-myers/celgene-bristol-myers-set-2-2-billion-termination-fee-for-their-mega-deal-idUKKCN1OY1CA

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-03/bristol-myers-squibb-to-buy-celgene-in-74-billion-pharma-deal

- Herbst-Bayliss, Svea; Erman, Michael (28 February 2019). "Starboard joins opposition to Bristol-Myers' $74 billion Celgene deal". Reuters. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

Starboard reported on Thursday that it now owns 4.4 million shares, or 0.3 percent of Bristol’s outstanding shares, while Wellington owns an 8 percent stake.

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-03/bristol-myers-squibb-to-buy-celgene-in-74-billion-pharma-deal

- Bristol-Myers Squibb Shareholders Approve Celgene Acquisition, PM BMS April 12, 2019, retrieved May 13, 2019

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb completes acquisition of Celgene". European Pharmaceutical Review. 22 November 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb completes divestment of consumer health business, UPSA to Taisho Pharma". Pharmabiz.com (Churnalism). India: Saffron Media. 2 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "Excedrin brand for sale". News > Fortune 500. CNN Money. Reuters. 12 January 2005.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb to Divest Three Consumer Brands" (Press release). Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. 21 September 1998. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016 – via PRNewswire.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb Plans To Divest U.S. And Canadian Consumer Medicines Business" (Press release). Bristol-Myers Squibb. 12 January 2005 – via BusinessWire.

- https://www.biospace.com/article/releases/amgen-to-acquire-otezla-for-13-4-billion-in-cash-or-approximately-11-2-billion-net-of-anticipated-future-cash-tax-benefits/?s=79

- https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-bristol-myers-divestiture-amgen/celgene-to-sell-psoriasis-drug-otezla-for-13-4-billion-to-amgen-idUKKCN1VG102

- "Bristol-Myers launches biotech targeting fibrosis, inflammation". BioPharma Dive. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb Revenue 2006-2018 | BMY". macrotrends.net. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb: Diversity and scale in biopharma". DHL. June 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "What Percent Does Bristol-Myers Squibb Spend On R&D, 30%, 40%, Or 50%?". Forbes. 28 November 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb". Fortune. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Selected Products of Bristol-Myers Squibb". © 2015 Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- Johnson DB, Peng C, Sosman JA (2015). "Nivolumab in melanoma: latest evidence and clinical potential". Ther Adv Med Oncol. 7 (2): 97–106. doi:10.1177/1758834014567469. PMC 4346215. PMID 25755682.

- "Generic Taxol Availability". drugs.com.

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb: the Pipeline". © 2015 Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Johns Hopkins, Bristol-Myers must face $1 billion syphilis infections suit". Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Mariani, Mike (28 May 2015). "The Guatemala Experiments". Pacific Standard. The Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media and Public Policy. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bristol-Myers Squibb. |

- Bristol-Myers Squibb worldwide locations

- "Bristol-Myers Squibb donates $6.9 million to benefit cancer patient". Drugstorenews.com.

- Business data for Bristol-Myers Squibb: