AgustaWestland AW109

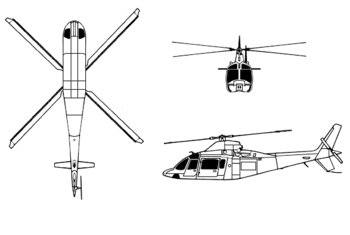

The AgustaWestland AW109, originally the Agusta A109 is a lightweight, twin-engine, eight-seat multi-purpose helicopter built by the Italian manufacturer Leonardo S.p.A. (formerly AgustaWestland, merged into the new Finmeccanica since 2016).[1] It was the first all-Italian helicopter to be mass-produced.[2]

| AW109 | |

|---|---|

| |

| An AW109E with No. 32 Squadron RAF in 2012 | |

| Role | Search and rescue/utility helicopter |

| Manufacturer | Agusta AgustaWestland Leonardo S.p.A. |

| First flight | 4 August 1971 |

| Introduction | 1976 |

| Status | Active service, in production |

| Primary users | Italian Army Rega (Swiss Air Rescue) South African Air Force Royal New Zealand Air Force |

| Produced | 1971–present |

| Unit cost |

US$ 6.3 million |

| Variants | AgustaWestland AW109S Grand |

| Developed into | AgustaWestland AW119 Koala |

Developed as the A109 by Agusta, it originally entered service in 1976 and has since been used in various roles, including light transport, medevac, search-and-rescue, and military roles. The AW109 has been in continuous production for 40 years. The AgustaWestland AW119 is a derivative of the AW109, the main difference being that it is powered only by a single engine.

Development

Origins

In the late 1960s, Agusta designed the A109 originally as a single-engine commercial helicopter.[3] However, it was soon realised that a twin-engine design was needed and it was re-designed in 1969 with two Allison 250-C14 turboshaft engines. A projected military version (the A109B) was considered early on but Agusta initially chose not to pursue immediate development, instead concentrating on the eight-seat A109C version.[4] The first of three prototypes made its maiden flight on 4 August 1971.[5] The A109's flight testing phase was prolonged, this was due in part to the discovery of dynamic instability which took a year to resolve via a modified transmission design;[6] this led to the first production aircraft being completed almost four years later in April 1975. On 1 June 1975, certification for visual flight rules (VFR) upon the A109 was received from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).[3]

In 1976, deliveries of production A109 to customers began. Advantages over the then-market leading Bell 206 were the A109's superior speed, twin-engine redundancy, and greater seating capacity.[3] In 1975, Agusta returned to the possibility of a military version, thus a series of trials were carried out between 1976 and 1977 using a total of five A109As outfitted with Hughes Aircraft-built TOW missiles. Two military versions emerged from this program, one was intended for light attack/close support missions and the other for shipboard operations.[7]

Further development

.jpg)

Improved civil versions quickly followed on from the initial production model; in 1981, a A109A Mk2 with a widened cabin was made available to operators.[8] In 1993, the A109 K2 was introduced using a new powerplant, a pair of Turbomeca Arriel 1K1 engines; this was followed by the A109 Power, broadly similar to the K2 except for the use of Pratt & Whitney Canada PW206 engines instead, in 1996.[3] According to AgustaWestland, the A109 Power was in service in 46 countries by 2008. In 2006, an enlarged variant, the A109S Grand, was introduced.[3]

The Agusta A109 was renamed the AW109 following the July 2000 merger of Finmeccanica S.p.A. and GKN plc's respective helicopter subsidiaries Agusta and Westland Helicopters to form AgustaWestland. Since the mid-1990s, fuselages for the AW109 have been manufactured by PZL-Świdnik, which became a subsidiary company of AgustaWestland in 2010. In June 2006, the 500th fuselage was delivered by PZL-Świdnik, marking 10 years of co-operation on the AW109 between the two companies.[9] In 2004, AgustaWestland formed a joint venture with Changhe Aircraft Industries Corporation for the support and production of the AW109; by 2009, the joint venture was capable to perform final assembly of the AW109, as well as manufacture major sections such as the fuselage.[10]

In February 2014, AgustaWestland revealed that it was developing the AW109 Trekker, an updated variant of the AW109. It is equipped with skid landing gear (the first twin-engine helicopter by AgustaWestland to have this feature) and is powered by a pair of FADEC-equipped Pratt & Whitney Canada PW207C engines; its avionics are supplied by Genesys Aerospace, which have been designed for single-pilot operations.[11] The Trekker reportedly advances upon the standard AW109's utility capabilities.[12] As per prior AW109 versions, the final assembly of the Trekker is undertaken at sites in both the US and Italy.[3][13]

Design

.jpg)

The AW109 is a lightweight twin-engine helicopter, known for its speed, elegant appearance and ease of control.[3][14][15] Since entering commercial service, several revisions and iterations have been made, frequently introducing new avionics and engine technologies. AgustaWestland have promoted the type for its multirole capabilities and serviceability. The type has proven highly popular with VIP/corporate customers; according to AgustaWestland, 50% of all of the AW109 Power variant had been sold in such configurations. Other roles for the AW109 have included emergency medical services, law enforcement, homeland security missions, harbor pilot shuttle duty, search and rescue, maritime operations, and military uses.[3] In 2008, AgustaWestland claimed the AW109 to be "one of the industry’s best-selling helicopters".[3]

A range of turboshaft powerplants have been used to power the numerous variants of the AW109, from the original Allison 250-C14 engines to the Turbomeca Arriel 1K1 and Pratt & Whitney Canada PW206 of more modern aircraft.[3] Powerplants can be replaced or swapped for during airframe overhauls, resulting in increasing lifting capacity and other performance changes. In the case of single-engine failure, the AW109 is intended to have a generous power reserve even on a single engine.[8] The engines drive a fully articulated four-blade rotor system.[16] Over time, more advanced rotor blade designs have been progressively adopted for the AW109's main and tail rotors, such as composite materials being used to replace bonded metal,[17] these improvements have typically been made with the aim of reducing operating costs and noise signature. According to Rotor&Wing, the type is well regarded for its "high, hot, and heavy" performance.[3]

According to AgustaWestland, the AW109 Power features various advanced avionics systems, these include a three-axis autopilot, an auto-coupled Instrument Landing System, integrated GPS, a Moving Map Display, weather radar, and a Traffic Alerting System.[18] These systems are designed to reduce pilot workload (the AW109 can be flown under single or dual-pilot instrument flight rules (IFR)) and enable the use of night vision goggles (NVG) to conduct day-or-night operations.[19] The AW109 has a forced trim system which can be readily and selectively activated by the controlling pilot using triggers located on the cyclic and collective which hold the control inputs at the last set position if activated.[3][16] All critical systems are deliberately redundant for fail-safe operations; the hydraulic system, hydraulic actuators, and electrical system are all dual-redundant, while the power inverters are triple-redundant.[8] The AW109 also has reduced maintenance requirements due to an emphasis on reliability across the range of components used.[19]

Some models of the AW109 feature the "quick convertible interior", a cabin configuration designed to be flexibly re-configured to allow the rotorcraft to be quickly adapted for different roles, such as the installation or removal of mission consoles or medical stretchers. Mission-specific equipment can also be installed in the externally accessible separate baggage compartment, which can be optionally expanded. Optional cabin equipment includes soundproofing, air conditioning, and bleed air heating.[19] Aftermarket cabin configurations are offered by third parties; Pininfarina and Versace have both offered designer interiors for the AW109, while Aerolite Max Bucher has developed a lightweight emergency medical service interior.[3] The majority of AW109s are fitted with a retractable wheeled tricycle undercarriage, providing greater comfort than skids and taxiing capability.[14][15] For shipboard operations, the wheeled landing gear is reinforced, deck mooring points are fixed across the lower fuselage, and extensive corrosion protection is typically applied.[20]

Optional mission equipment for the AW109 has included dual controls, a rotor brake, windshield wipers, a fixed cargo hook, snow skis, external loudspeakers, wire-strike protection system, engine particle separator, engine compartment fire extinguishers, datalink, and rappelling fittings.[19] A range of armaments can be installed upon the AW109, including pintle-mounted machine guns, machine gun pods, 20mm cannons, rocket pods, anti-tank missiles and air-to-air missiles.[20][21] Those AW109s operated by the U.S. Coast Guard, later designated as MH-68A, had the following equipment installed: a rescue hoist, emergency floats, FLIR, Spectrolab NightSun search light, a 7.62 mm M240D machine gun and a Barrett M107 semi-automatic .50 caliber anti-material rifle with laser sight.[22]

Operational history

Various branches of the Italian military have operated variants of the AW109; the Guardia di Finanza has operated its own variant of the AW109 since the 1980s for border patrol and customs duties, by 2010, it was in the process of replacing its original AW109s with a new-generation of AW109s.[2]

In 1982, the Argentine Army Aviation deployed three A109As to the Falkland Islands during the Falklands War. They operated with the helicopter fleet (9 UH-1H, 2 CH-47C and 2 Pumas) in reconnaissance and liaison roles. One of the helicopters was destroyed on the ground by a British Harrier attack; the others were captured and sent to Europe in HMS Fearless (L10). The British Army Air Corps decided to use those helicopters in domestic operations (being flown by 8 Flight AAC to support SAS regiment deployments in the UK), alongside two additional A109 which were purchased later following favorable use of the first two; all were retired in 2009.[23][24] The improved AW109E and SP – Grand New versions have also been operated by No. 32 Squadron of the Royal Air Force to transport members of the British Royal Family.[25]

In 1988, 46 A109s were sold to the Belgian Armed Forces; it was later alleged that Agusta had given the Belgian Socialist Party over 50 million Belgian francs as a bribe to secure the sale. The resulting scandal led to the resignation and later conviction of NATO Secretary General Willy Claes.[26] Belgium has operated an A109 aerial display team.[27] In early 2013, a pair of Belgian AW109s were deployed to Sévaré, Mali, to perform medical evacuation mission in support of the French-led Operation Serval.[28] In June 2013, Belgian newspaper La Libre Belgique alleged that several former Belgian military helicopters had been sold via a private company to South Sudan in violation of a European Union embargo on weapons sales.[29][30]

In the 1990s, the US Coast Guard, seeking to tackle drug trafficking on small speed boats via armed aerial interdiction helicopters, evaluated several options and selected the AW109 as the winner. For a number of years, eight armed AW109s, designated MH-68A Sting Ray, were leased from AgustaWestland and deployed at Coast Guard land facilities and onboard cutters. Positive experience with the AW109 led to the Coast Guard deciding to arm all of its helicopters and, following adaptions of their existing assets, the AW109s were returned after the lease expired.[3]

In September 1999, the South African Air Force (SAAF) placed an order for 30 AW109s;[3] 25 of the 30 rotorcraft were assembled locally by Denel Aviation, starting in 2003.[31][32] As many as 16 SAAF AW109s were deployed for patrol, utility, and medical evacuation missions during the 2010 FIFA World Cup.[33] In July 2013, the SAAF reported that 18 AW109s had effectively been grounded due to lack of funding, these rotorcraft being only occasionally activated but not conducting flights; in 2013, only 71 flight hours were allocated to the whole AW109 fleet. The type may be reduced to flying VIPs rather than being operationally capable; South Africa is also considering selling a number of AW109s, and may cease helicopter operations altogether.[34]

In 2001, 20 AW109s were ordered for the Swedish Armed Forces,[3] receiving the Swedish military designation of Hkp 15. In 2010, it was reported that considerable demands were being placed upon the AW109 fleet, in part due to the delayed delivery of the NHIndustries NH90.[35] In early 2015, a pair of Swedish AW109s were deployed on board the Royal Netherlands Navy ship HNLMS Johan de Witt, their first-ever deployment on board a foreign vessel, in support of a multinational anti-piracy mission off the coast of Somalia; the AW109 reportedly achieve a 100% availability rate over the course of three months.[36]

Between 2007 and 2012, three AW109E Power helicopters were operated under lease by the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) to train naval aircrew.[37]

In May 2008, the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) placed an order for five AW109LUH rotorcraft to replace their aging Bell 47 Sioux in a training capacity; they are also used in the utility role to complement the larger NHIndustries NH90 and has seen limited use in VIP missions.[38]

In August 2008, Scott Kasprowicz and Steve Sheik broke the round-the-world speed record using a factory-standard AgustaWestland AW109S Grand, with a time of 11 days, 7 hours and 2 minutes. The AW109S Grand is also recorded as being the fastest helicopter from New York to Los Angeles.[39][40]

In 2013, the Philippine Air Force (PAF) and the Philippine Navy independently ordered batches of AW109 Power rotorcraft; additional AW109s were ordered in 2014.[41] The PAF AW109s are used as armed gunships, while both armed and unarmed AW109s are operated by the Philippine Navy.[42][43] During the Battle of Marawi AW109s were widely used against the ISIS-affiliated Maute Group.[44]

Variants

- A109A

- The first production model, powered by two Allison Model 250-C20 turboshaft engines. It made its first flight on 4 August 1971. Initially, the A109 was marketed under the name of "Hirundo" (Latin for the swallow), but this was dropped within a few years.

- A109A EOA

- Military version for the Italian Army.

- A109A Mk.II

- Upgraded civilian version of the A109A.

- A109A Mk.II MAX

- Aeromedical evacuation version based on A109A Mk.II with extra wide cabin and access doors hinged top and bottom, rather than to one side.

- A109B

- Unbuilt military version.

- A109BA

- Version created for the Belgian Army. Based on the A109C with fixed landing gear.

- A109C

- Eight-seat civil version, powered by two Allison Model 250-C20R-1 turboshaft engines.[15]

- A109C MAX

- Aeromedical evacuation version based on A109C with extra-wide cabin and access doors hinged top and bottom, rather than to one side.[45]

- A109D

- One prototype only

- A109E Power

- Upgraded civilian version, initially powered by two Turbomeca Arrius 2K1 engines. Later the manufacturer introduced an option for two Pratt & Whitney PW206C engines to be used – both versions remain known as the A109E. Marketed as the AW109E and Power.

- A109E Power Elite

- A stretched cabin version of A109E Power. Features a glass cockpit with two complete sets of pilot instruments and navigation systems, including a three-axis autopilot, an auto-coupled Instrument Landing System and GPS.[18]

- A109LUH

- Military LUH "Light Utility Helicopter" variant based on the A109E Power. Operators include South African Air Force, Swedish Air Force, Royal New Zealand Air Force, Nigerian Air Force, as well as Algeria and Malaysia. Known as the Hkp15A (utility variant) and 15B (ship-borne search and rescue variant) with the Swedish Air Force.

- MH-68A

- Eight A109E Power aircraft were used by the United States Coast Guard Helicopter Interdiction Tactical Squadron Jacksonville (HITRON Jacksonville) as short-range armed interdiction helicopters from 2000 until 2008, when they were replaced with MH-65C Dolphins.[46] Agusta designated these armed interdiction aircraft as "Mako" until the U.S. Coast Guard officially named it the MH-68A Stingray in 2003.[22]

- A109K

- Military version.

- A109K2

- High-altitude and high-temperature operations with fixed wheels rather than the retractable wheels of most A109 variants. Typically used by police, search and rescue, and air ambulance operators.

- A109M

- Military version.

- A109 km

- Military version for high altitude and high temperature operations.

- A109KN

- Naval version.

- A109CM

- Standard military version.

- A109GdiF

- Version for Guardia di Finanza, the Italian Finance Guard.

- A109S Grand

- Marketed as the AW109 Grand, it is a lengthened cabin-upgraded civilian version with two Pratt & Whitney Canada PW207 engines and lengthened main rotor blades with different tip design from the Power version.

- AW109SP

- AW109 Grand New

- single pilot IFR, TAWS and EVS, especially for EMS.

- AW109 Trekker

- A variant of the AW109S Grand with fixed landing skids.[47]

- CA109

- Chinese direct copy of the AW109E for China mainland market by Jiangxi Changhe Agusta Helicopter Co., Ltd., a Leonardo Helicopter Division(formerly AgustaWestland) and Changhe Aviation Industries Joint Venture Company established in 2005.[48]

Operators

The AW109 is flown by a range of operators including private companies, military services, emergency services and air charter companies.

Military and government operators

.jpg)

- Polizia di Stato[55]

- Carabinieri[56][57]

- Guardia di Finanza[58]

- Italian Army[51]

- Vigili del Fuoco[59]

- State Forestry Corps[60]

_15025_25_levels.jpg)

.jpg)

Former military operators

- Italian Air Force operated 3 aircraft[70]

Accidents

- On 16 January 2013: Vauxhall helicopter crash, an AW109 on charter to Rotormotion clipped a construction crane attached to the St George Wharf Tower in Vauxhall, London, before crashing to the ground and bursting into flames, killing the pilot and a person on the ground. The helicopter was completely destroyed and the crane was also seriously damaged.[77]

- On 24 December 2018: in the 2018 Puebla helicopter crash, an AW109 taking off from an airport on the outskirts of Puebla on a flight to Mexico City crashed about 3.5 miles north of the airport. Gov. Martha Erika Alonso and ex-Gov. Rafael Moreno Valle died in this incident.[78][79]

- On 10 June 2019: in the 2019 New York City helicopter crash, an AW109E crashed at approximately 1:43 p.m. ET on the roof of the AXA Equitable Center at 787 Seventh Avenue in New York City, killing the pilot and creating a fire.[80]

Displayed

- A109A at Fleet Air Arm Museum, Yeovil, England. Former AE-331 of the Argentine Army Aviation, captured in the Falklands War.[81]

Specifications (AW109 Power with PW206C) 2850 Kilo version

.jpg)

Data from Leonardo "AW109 Power".

General characteristics

- Crew: 1 or 2

- Capacity: 6 or 7 passengers

- Length: 11.448 m (37 ft 7 in) fuselage

- Height: 3.50 m (11 ft 6 in)

- Empty weight: 1,590 kg (3,505 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 2,850 kg (6,283 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney Canada PW206C Turboshaft engine, 418 kW (560 hp) each

- Main rotor diameter: 11.00 m (36 ft 1 in)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 311 km/h (193 mph, 168 kn)

- Cruise speed: 285 km/h (177 mph, 154 kn)

- Never exceed speed: 311 km/h (193 mph, 168 kn)

- Ferry range: 932 km (579 mi, 503 nmi)

- Rate of climb: 9.8 m/s (1,930 ft/min)

Notable appearances in media

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Bell 222/230

- Bell 427

- Bell 429 GlobalRanger

- Bell 430

- Eurocopter AS365 Dauphin

- Eurocopter EC135

- MD Helicopters MD Explorer

- Sikorsky S-76

Related lists

References

Citations

- "Finmeccanica Approves Merger And Spin-off Operations For The Implementation Of The Divisionalisation Process". Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- "Law Enforcement: Italy." Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Police Aviation News, No. 175. November 2010.

- Ernie Stephens and James T. McKenna. "Operators’ Report: Fast, Beautiful Flier." Archived 4 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine Rotor & Wing, 1 May 2008.

- Air International October 1978, pp. 160–161.

- Air International October 1978, p. 161.

- Moll 1992, p. 68.

- "AgustaWestland makes its mark with technology and innovation." Archived 23 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Professional Pilot, July 2012.

- McClellan 1989, p. 38.

- "PZL-Świdnik deliver 500th airframe to AgustaWestland". PZL-Świdnik SA. Archived from the original on 7 September 2006.

- Cliff, Ohlandt and Yang 2011, p. 59.

- Huber, Mark. "AgustaWestland sees Latin America in “positive climb.”" Archived 8 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine AIN Online, 7 August 2015.

- Thurber, Mark. "AgustaWestland Enjoys Steady Growth in European Market." Archived 26 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine AIN Online, 20 May 2014.

- Bergqvist, Pia. "AgustaWestland Unveils Skid-Equipped AW109 Trekker." Archived 6 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine Flying Magazine, 27 February 2015.

- McClellan 1989, p. 34.

- Moll 1992, p. 70.

- McClellan 1989, p. 37.

- Moll 1992, p. 64.

- "RAF – Agusta A 109 E". Raf.mod.uk. 25 April 2012. Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- "AW109 Power: Law Enforcement." AgustaWestland, Retrieved: 18 October 2015.

- "PN inspects 2 attack choppers." Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Manila Standard, 23 May 2015.

- "AW109 LUH: The cost-effective force multiplier." Archived 16 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine AgustaWestland, Retrieved: 22 October 2015.

- Crawford, Steve (2003). Twenty-first century military helicopters: today's fighting gunships. St. Paul, MN.: MBI Publishing Company. p. 85. ISBN 0-7603-1504-3.

- "Agusta A109a in Argentina". helis.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- "A109 Hirundo – Army Air Corps". Touchdown Aviation. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- Stibbe, Matthew. "The Royal Squadron." Archived 24 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine Forbes, 11 January 2013.

- "Arrest warrant issued for Serge Dassault." Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 15 May 1996.

- "A109 Display Team." Facebook, Retrieved: 18 October 2015.

- Fiorenza, Nicholas. "First Belgian A109 Medevac Mission in Mali." Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Week, 14 February 2013.

- "Les 12 Agusta que l’armée belge ne pouvait pas vendre." Archived 15 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine La Libre Belgique, 25 June 2013.

- "From Belgium to South Sudan: the controversial selling of 12 Agusta helicopters." Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Investigative reporting project Italy, 29 June 2013.

- "Denel Aviation Has Started Final Assembly of the SAAF A109 Light Utility Helicopter (LUH)." AgustaWestland, 17 February 2003.

- "First Denel Agusta A109 helicopter takes off." Engineering News, 13 September 2004.

- "AgustaWestland holds first AW109 LUH/LOH Operators Conference." Shephard Media, 6 December 2010.

- "South African airforce in crisis." Archived 26 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine Timeslive.co.za, 24 July 2013.

- O'Dwyer, Gerard. "Sweden Moves Helos From Piracy Ops to Battle Group." defensenews.com, 21 July 2010.

- Hoyle, Craig. "Swedish AW109 performing well for EU off Somali coast." Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 5 May 2015.

- "Navy’s RMI retires A109, prepares for 429." Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Australian Aviation, 16 March 2012.

- "A109 Light Utility Helicopter." Archived 23 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine airforce.mil.nz, Retrieved: 19 October 2015.

- "History of Rotorcraft World Records, List of records established by the 'A109S Grand'". Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Archived from the original on 29 July 2010.

- "AgustaWestland news archive, August 2008". Agustawestland.com. 18 August 2008. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- "Philippine Navy Signs Contract for Two Additional AW109 Power Helicopters." Archived 18 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine AgustaWestland, 11 February 2014.

- "Philippine Navy Weaponizes Helicopters to Deploy on Frigates." Archived 8 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine Sputnik News, 20 August 2015.

- "Philippine Air Force Signs Contract for Eight AW109 Power helicopters." AgustaWestland, 6 November 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Moll 1992, p. 67.

- MCH: Project Description, U.S. Coast Guard Short Range Recovery (SRR) Helicopter.

- "AgustaWestland reveals new AW109 variant". shephardmedia.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- Jiangxi Changhe Agusta Helicopter Co., Ltd. Archived 20 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Les nouveaux hélicoptères de la Gendarmerie Nationale prennent leur envol". Copyright (c) Secret Difa3. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Number and type of AW Helicopters in service in Algeria". Copyright (c) Secret Difa3. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- "World Air Forces 2019". Flightglobal Insight. 2019. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- "Bulgarian Border Police Takes Delivery Of Its First AW109 Power". Aviation News. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Carabineros de Chile Expand Their AW109 Power Fleet". Aviation News. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Hellenic Air Force – A-109 Hirundo". GH. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "ELICOTTERI POLIZIA VENEZIA". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Ccarabinieri A 109E". carabinieri.it. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Carabinieri – AgustaWestland AW-109N". Demand media. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Guardia di Finanza 'A109Nexus". gdf.gov.it. Archived from the original on 23 April 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "AW 109 Vigili del Fuoco". Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Roelofs, Erik (April 2012). "Italy's Flying Foresters". Air International. Vol. 82 no. 4. pp. 78–81. ISSN 0306-5634.

- "Tokyo Metropolitan Police selects Leonardo-Finmeccanica AW109 Trekker". Leonardo. 17 June 2016. Archived from the original on 22 June 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- "AgustaWestland AW109 Power Helicopters Ordered By Ministry Of The Interior Of Latvia Enter Service". Aviation News. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Slovenia Announce The Procurement Of One A109 Power Helicopter". AgustaWestland. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "SLOVENIAN POLICE HELICOPTER UNIT" (PDF). policija.si. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Martin, Guy (June 2019). "AW109SPs on port duties". Air International. Vol. 96 no. 6. p. 117. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Dominguez, Gabriel; Gibson, Neil (4 August 2017). "Turkmenistan releases footage of AW109 helos conducting live-fire drill". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "Uganda Orders W-3A, A109 Helicopters". DefenceWeb. 15 July 2014. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- "Agusta 109 in Argentine military service". gacetaeronautica.com. Archived from the original on 20 July 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Australian Navy retires the A109". shephardmedia.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Italian Air Force Aircraft Types". aeroflight.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "FAP Historia Los Años 90 (1990–1999)". fuerzaaerea.mil.py. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- Barrie Flight International 10–16 September 1997, p. 62.

- "8 Flight Army Air Corps". eliteukforces.info. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "MH-68A Stingray / Agusta A109E". globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Venezuela Army Aviation". aeroflight.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "Ejercito de Venezuela Agusta A109 Hirundo". Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "London helicopter crash: Two die in Vauxhall crane accident". BBC Online. 16 January 2013. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- "Mexico: Helicopter crash claims Puebla governor, ex-governor". 24 December 2018. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Mexican governor and politician husband killed in helicopter crash". 24 December 2018. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Helicopter crashes into New York City building". 10 June 2019. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Exhibitions – Reserve Collections – Agusta 109A (AE-331)". Fleet Air Arm Museum. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

Bibliography

- "The A-109A – Agusta's Pace-Setter". Air International, October 1978, Vol. 15 No. 4. pp. 159–166, 198.

- Cliff, Roger. Chad J. R. Ohlandt and David Yang. Ready for Takeoff: China's Advancing Aerospace Industry. "Rand Corporation", 2011. ISBN 0-8330-5208-X.

- Barrie, Douglas. "Air Forces of the World". Flight International, 10–16 September 1997, Vol. 152 No. 4591. pp. 35–71.

- Hoyle, Craig. "World Air Forces Directory". Flight International, 13–19 December 2011, Vol. 180 No. 5321. pp. 26–52.

- McClellan, J. Mac. Agusta A109 Mk II Plus. "Flying Magazine", February 1989. Vol. 116. No. 2. ISSN 0015-4806. pp. 34–38.

- Moll, Nigel. Agusta A109A: City Slicker. "Flying Magazine", April 1992. Vol. 119. No. 4. ISSN 0015-4806. pp. 62–70.