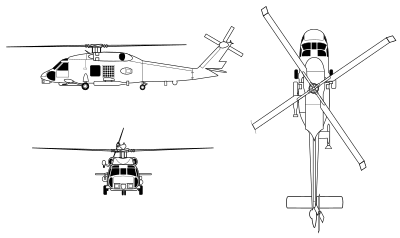

Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk

The Sikorsky SH-60/MH-60 Seahawk (or Sea Hawk) is a twin turboshaft engine, multi-mission United States Navy helicopter based on the United States Army UH-60 Black Hawk and a member of the Sikorsky S-70 family. The most significant modifications are the folding main rotor and a hinged tail to reduce its footprint aboard ships.

| SH-60 / HH-60H / MH-60 Seahawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| A U.S. Navy SH-60B landing on USS Abraham Lincoln. | |

| Role | Utility maritime helicopter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Sikorsky Aircraft |

| First flight | 12 December 1979 |

| Introduction | 1984 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Navy Royal Australian Navy Turkish Naval Forces Spanish Navy |

| Produced | 1979–present |

| Number built | 938[1][2] |

| Unit cost | |

| Developed from | Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk |

| Variants | Sikorsky HH-60 Jayhawk Mitsubishi SH-60 |

The U.S. Navy uses the H-60 airframe under the model designations SH-60B, SH-60F, HH-60H, MH-60R, and MH-60S. Able to deploy aboard any air-capable frigate, destroyer, cruiser, fast combat support ship, amphibious assault ship, Littoral combat ship or aircraft carrier, the Seahawk can handle anti-submarine warfare (ASW), anti-surface warfare (ASUW), naval special warfare (NSW) insertion, search and rescue (SAR), combat search and rescue (CSAR), vertical replenishment (VERTREP), and medical evacuation (MEDEVAC).

Design and development

Origins

During the 1970s, the U.S. Navy began looking for a new helicopter to replace the Kaman SH-2 Seasprite.[5] The SH-2 Seasprite was used by the Navy as its platform for the Light Airborne Multi-Purpose System (LAMPS) Mark I avionics suite for maritime warfare and a secondary search and rescue capability. Advances in sensor and avionic technology lead to the LAMPS Mk II suite being developed by the Naval Air Development Center. The Navy then conducted a competition in 1974 to develop the Lamps MK III concept which would integrate both the aircraft and shipboard systems. The Navy selected IBM Federal Systems to be the Prime systems integrator for the Lamps MK III concept.

Since the SH-2 was not large enough to carry the Navy's required equipment a new airframe was required. In the mid-1970s, the Army evaluated the Sikorsky YUH-60 and Boeing Vertol YUH-61 for its Utility Tactical Transport Aircraft System (UTTAS) competition.[6] Navy based its requirements on the Army's UTTAS specification to decrease costs from commonality to be the new airframe to carry the Lamps MK III avionics.[5] Sikorsky and Boeing-Vertol submitted proposals for Navy versions of their Army UTTAS helicopters in April 1977 for review. The Navy also looked at helicopters being produced by Bell, Kaman, Westland and MBB, but these were too small for the mission. In early 1978 the Navy selected Sikorsky's S-70B design,[5] which was designated "SH-60B Seahawk".

SH-60B Seahawk

IBM was the prime systems integrator for the Lamps MK III with Sikorsky as the airframe manufacturer. The SH-60B maintained 83% commonality with the UH-60A.[7] The main changes were corrosion protection, more powerful T700 engines, single-stage oleo main landing gear, removal of the left side door, adding two weapon pylons, and shifting the tail landing gear 13 feet (3.96 m) forward to reduce the footprint for shipboard landing. Other changes included larger fuel cells, an electric blade folding system, folding horizontal stabilators for storage, and adding a 25-tube pneumatic sonobuoy launcher on the left side.[8] An emergency flotation system was originally installed in the stub wing fairings of the main landing gear; however, it was found to be impractical and possibly impede emergency egress, and thus was subsequently removed. Five YSH-60B Seahawk LAMPS III prototypes were ordered. The first YSH-60B flight occurred on 12 December 1979. The first production SH-60B made its first flight on 11 February 1983. The SH-60B entered operational service in 1984 with first operational deployment in 1985.[6]

The SH-60B is deployed primarily aboard frigates, destroyers, and cruisers. The primary missions of the SH-60B are surface warfare and anti-submarine warfare. It carries a complex system of sensors including a towed Magnetic Anomaly Detector (MAD) and air-launched sonobuoys. Other sensors include the APS-124 search radar, ALQ-142 ESM system and optional nose-mounted forward looking infrared (FLIR) turret. Munitions carried include the Mk 46, Mk 50, or Mark 54 Lightweight Torpedo, AGM-114 Hellfire missile, and a single cabin-door-mounted M60D/M240 7.62 mm (0.30 in) machine gun or GAU-16 .50 in (12.7 mm) machine gun.

A standard crew for a SH-60B is one pilot, one ATO/Co-Pilot (Airborne Tactical Officer), and an enlisted aviation warfare systems operator (sensor operator). The U.S. Navy operated the SH-60B in Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron, Light (HSL) squadrons. All HSL squadrons were redesignated Helicopter Maritime Strike (HSM) squadrons and transitioned to the MH-60R between 2006 and 2015.

The SH-60J is a version of the SH-60B for the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force. The SH-60K is a modified version of the SH-60J. The SH-60J and SH-60K are built under license by Mitsubishi in Japan.[9][10]

SH-60F

After the SH-60B entered service,[11] the Navy conducted a competition to replace the SH-3 Sea King. The competitors were Sikorsky, Kaman and IBM (avionics only). Sikorsky began development of this variant in March 1985. In January 1986, seven SH-60Fs were ordered including two prototypes (BuNos 163282/3).[12] The first example flew on 19 March 1987.[13] The SH-60F was based on the SH-60B airframe, but with upgraded SH-3H avionics.

The SH-60F primarily served as the carrier battle group's primary antisubmarine warfare (ASW) aircraft. The helicopter hunted submarines with its AQS-13F dipping sonar, and carried a 6-tube sonobuoy launcher. The SH-60F is unofficially named "Oceanhawk".[13] The SH-60F can carry Mk 46, Mk 50, or Mk 54 torpedoes for its offensive weapons, and it has a choice of fuselage-mounted machine guns, including the M60D, M240D, and GAU-16 (.50 caliber) for self-defense. The standard aircrew consists of one pilot, one co-pilot, one tactical sensor operator (TSO), and one acoustic sensor operator (ASO). The SH-60F was operated by the U.S Navy's Helicopter Antisubmarine (HS) squadrons until they were redesignated Helicopter Sea Combat (HSC) squadrons transitioned to the MH-60S. The last HS squadron completed its transition in 2016.

HH-60H

The HH-60H was developed in conjunction with the US Coast Guard's HH-60J, beginning in September 1986 with a contract for the first five helicopters with Sikorsky as the prime contractor. The variant's first flight occurred on 17 August 1988. Deliveries of the HH-60H began in 1989. The variant earned initial operating capability in April 1990 and was deployed to Desert Storm with HCS-4 and HCS-5 in 1991.[13] The HH-60H's official DoD and Sikorsky name is Seahawk, though it has been called "Rescue Hawk".[14]

Based on the SH-60F, the HH-60H is the primary combat search and rescue (CSAR), naval special warfare (NSW) and anti-surface warfare (ASUW) helicopter. It carries various defensive and offensive sensors. These include a FLIR turret with laser designator, and the Aircraft Survival Equipment (ASE) package including the ALQ-144 Infrared Jammer, AVR-2 Laser Detectors, APR-39(V)2 Radar Detectors, AAR-47 Missile Launch Detectors and ALE-47 chaff/flare dispensers. Engine exhaust deflectors provide infrared thermal reduction reducing the threat of heat-seeking missiles. The HH-60H can carry up to four AGM-114 Hellfire missiles on an extended wing using the M299 launcher and a variety of mountable guns including M60D, M240, GAU-16 and GAU-17/A machine guns.

The HH-60H's standard crew is pilot, copilot, an enlisted crew chief, and two door gunners or one rescue swimmer. Originally operated by HCS-5 and HCS-4 (later HSC-84), these two special USNR squadrons were established with the primary mission of Naval Special Warfare and Combat Search and Rescue (CSAR). Due to SOCOM budget issues the squadrons were deactivated in 2006 and 2016 respectively. The HH-60H was also operated by Helicopter Antisubmarine (HS) squadrons with a standard dispersal of six F-models and two or three H-models before the transition of HS squadrons to HSC squadrons equipped with the MH-60S, the last of which completed its transition in 2016. The only squadron equipped with the HH-60H as of 2016 is HSC-85, one of only two remaining USNR helicopter squadrons (the other being HSM-60 equipped with the MH-60R). In Iraq, HH-60Hs were used by the Navy, assisting the Army, for MEDEVAC purposes and special operations missions.

MH-60R

The MH-60R was originally known as "LAMPS Mark III Block II Upgrade" when development began in 1993 with Lockheed Martin (formerly IBM/Loral). Two SH-60Bs were converted by Sikorsky, the first of which made its maiden flight on 22 December 1999. Designated YSH-60R, they were delivered to NAS Patuxent River in 2001 for flight testing. The production variant was redesignated MH-60R to match its multi-mission capability.[15] The MH-60R was formally deployed by the US Navy in 2006.[16]

The MH-60R is designed to combine the features of the SH-60B and SH-60F.[17] Its avionics includes dual controls and instead of the complex array of dials and gauges in Bravo and Foxtrot aircraft, 4 fully integrated 8" x 10" night vision goggle-compatible and sunlight-readable color multi-function displays, all part of glass cockpit produced by Owego Helo Systems division of Lockheed Martin.[18] Onboard sensors include: AN/AAR-47 Missile Approach Warning System by ATK,[18]Raytheon AN/AAS-44 electro-optical system that integrates FLIR and laser rangefinder,[18]AN/ALE-39 decoy dispenser and AN/ALQ-144 infrared jammer by BAE Systems,[18]AN/ALQ-210 electronic support measures system by Lockheed Martin,[18]AN/APS-147 multi-mode radar/IFF interrogator, which during a mid-life technology insertion project is subsequently replaced by AN/APS-153 Multi-Mode Radar with Automatic Radar Periscope Detection and Discrimination (ARPDD) capability,[19]and both radars were developed by Telephonics,[20][18]a more advanced AN/AQS-22 advanced airborne low-frequency sonar (ALFS) jointly developed by Raytheon & Thales,[18] AN/ARC-210 voice radio by Rockwell Collins,[18]an advanced airborne fleet data link AN/SRQ-4 Hawklink with radio terminal set AN/ARQ-59 radio terminal, both by L3Harris,[21][22][23]and LN-100G dual-embedded global positioning system and inertial navigation system by Northrop Grumman Litton division.[18]MH-60R does not carry the MAD suite.

Offensive capabilities are improved by the addition of new Mk-54 air-launched torpedoes and Hellfire missiles. All Helicopter Anti-Submarine Light (HSL) squadrons that receive the Romeo are redesignated Helicopter, Strike Maritime (HSM) squadrons.[24]

MH-60S

_as_the_ship_is_anchored_offshore_near_Port-Au-Prince.jpg)

.jpg)

The Navy decided to replace its venerable CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters in 1997. After sea demonstrations by a converted UH-60, the Navy awarded a production contract to Sikorsky for the CH-60S in 1998. The variant first flew on 27 January 2000 and it began flight testing later that year. The CH-60S was redesignated MH-60S in February 2001 to reflect its planned multi-mission use.[25] The MH-60S is based on the UH-60L and has many naval SH-60 features.[26] Unlike all other Navy H-60s, the MH-60S is not based on the original S-70B/SH-60B platform with its forward-mounted twin tail-gear and single starboard sliding cabin door. Instead, the S-model is a hybrid, featuring the main fuselage of the S-70A/UH-60, with large sliding doors on both sides of the cabin and a single aft-mounted tail wheel; and the engines, drivetrain and rotors of the S-70B/SH-60.[27][26] It also includes the integrated glass cockpit developed by Lockheed Martin for the MH-60R and shares some of the same avionics/weapons systems.

It is deployed aboard aircraft carriers, amphibious assault ships, Maritime Sealift Command ships, and fast combat support ships. Its missions include vertical replenishment, medical evacuation, combat search and rescue, anti-surface warfare, maritime interdiction, close air support, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, and special warfare support. The MH-60S is to deploy with the AQS-20A Mine Detection System and an Airborne Laser Mine Detection System (ALMDS) for identifying submerged objects in coastal waters. It is the first US Navy helicopter to field a glass cockpit, relaying flight information via four digital monitors. The primary means of defense has been with door-mounted machine guns such as the M60D, M240D, or GAU-17/A. A "batwing" Armed Helo Kit based on the Army's UH-60L was developed to accommodate Hellfire missiles, Hydra 70 2.75 inch rockets, or larger guns. The MH-60S can be equipped with a nose-mounted forward looking infrared (FLIR) turret to be used in conjunction with Hellfire missiles; it also carries the ALQ-144 Infrared Jammer.

The MH-60S is unofficially known as the "Knighthawk", referring to the preceding Sea Knight, though "Seahawk" is its official DoD name.[29] A standard crew for the MH-60S is one pilot, one copilot and two tactical aircrewmen depending on mission. With the retirement of the Sea Knight, the squadron designation of Helicopter Combat Support Squadron (HC) was also retired from the Navy. Operating MH-60S squadrons were re-designated Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron (HSC).[24] The MH-60S was to be used for mine clearing from littoral combat ships, but testing found it lacks the power to safely tow the detection equipment.[30]

On 6 August 2014, the U.S. Navy forward deployed the Airborne Laser Mine Detection System (ALMDS) to the U.S. 5th Fleet. The ALMDS is a sensor system designed to detect, classify, and localize floating and near-surface moored mines in littoral zones, straits, and choke points. The system is operated from an MH-60S, which gives it a countermine role traditionally handled by the MH-53E Sea Dragon, allowing smaller ships the MH-53E can't operate from to be used in the role. The ALMDS beams a laser into the water to pick up reflections from things it bounces off of, then uses that data to produce a video image for technicians on the ground to determine if the object is a mine.[31]

The MH-60S will utilize the BAE Systems Archerfish remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to seek out and destroy naval mines from the air. Selected as a concept in 2003 by the Navy as part of the Airborne Mine Neutralization System (AMNS) program and developed since 2007, the Archerfish is dropped into the water from its launch cradle, where its human operator remotely guides it down towards the mine using a fiber optics communications cable that leads back up to the helicopter. Using sonar and low-light video, it locates the mine, and is then instructed to shoot a shaped charge explosive to detonate it. BAE was awarded a contract to build and deliver the ROVs in April 2016.[32]

Operational history

U.S. Navy

The Navy received the first production SH-60B in February 1983 and assigned it to squadron HSL-41.[33][34] The helicopter entered service in 1984,[35] and began its first deployment in 1985.[33]

.jpg)

The SH-60F entered operational service on 22 June 1989 with Helicopter Antisubmarine Squadron 10 (HS-10) at NAS North Island.[25] SH-60F squadrons planned to shift from the SH-60F to the MH-60S from 2005 to 2011 and were to be redesignated Helicopter Sea Combat (HSC).[36]

As one of the two squadrons in the US Navy dedicated to Naval Special Warfare support and combat search and rescue, the HCS-5 Firehawks squadron deployed to Iraq for Operation Iraqi Freedom in March 2003. The squadron completed 900 combat air missions and over 1,700 combat flight hours. The majority of their flights in the Iraqi theater supported special operations ground forces missions.

A west coast Fleet Replacement Squadron (FRS), Helicopter Maritime Strike Squadron (HSM) 41, received the MH-60R aircraft in December 2005 and began training the first set of pilots. In 2007, the R-model successfully underwent final testing for incorporation into the fleet. In August 2008, the first 11 combat-ready Romeos arrived at HSM-71, a squadron assigned to the carrier John C. Stennis. The primary missions of the MH-60R are anti-surface and anti-submarine warfare. According to Lockheed Martin, "secondary missions include search and rescue, vertical replenishment, naval surface fire support, logistics support, personnel transport, medical evacuation and communications and data relay."[37]

HSL squadrons in the US have been incrementally transitioning to the MH-60R and have nearly completed the transition. The first MH-60Rs in Japan arrived in October 2012. The recipient was HSM-51, the Navy's forward–deployed LAMPS squadron, home based in Atsugi, Japan. The Warlords transitioned from the SH-60B throughout 2013, and shifted each detachment to the new aircraft as they returned from deployments. HSM-51 will have all MH-60R aircraft at the end of 2013. The Warlords are joined by the Saberhawks of HSM-77.

On 23 July 2013, Sikorsky delivered the 400th MH-60, an MH-60R, to the U.S. Navy. This included 166 MH-60R versions and 234 MH-60S versions. The MH-60S is in production until 2015 and will total a fleet of 275 aircraft, and the MH-60R is in production until 2017 and will total a fleet of 291 aircraft. The two models have flown 660,000 flight hours. Seahawk helicopters are to remain in Navy service into the 2030s.[38]

The SH-60B Seahawk completed its last active-duty deployment for the U.S. Navy in late April 2015 after a seven-month deployment aboard USS Gary. After 32 years and over 3.6 million hours of service, the SH-60B was formally retired from U.S. Navy service during a ceremony on 11 May 2015 at Naval Air Station North Island.[39][40] In late November 2015 USS Theodore Roosevelt returned from its deployment, ending the last active-duty operational deployment of both the SH-60F and HH-60H. The models are to be transferred to other squadrons or placed in storage.[41]

Other and potential users

Spain ordered 12 S-70B Seahawks for its Navy.[42] Spain requested six refurbished SH-60Fs through a Foreign Military Sale in September 2010.[43][44]

Australia originally acquired 16 S-70Bs the in the 1980s. Australia requested approval to buy 24 MH-60Rs through a Foreign Military Sale in July 2010.[45] The MH-60R and the NHIndustries NH90 were evaluated by the Royal Australian Navy. On 16 June 2011, it was announced that Australia would purchase 24 of the MH-60R variant, to come into service between 2014 and 2020.[46] The helicopter was selected to replace the RAN's older Seahawks.[47][48] The last of the 24 MH-60Rs was delivered to the RAN in September 2016.[49] The S-70B-2 Seahawks were retired in December 2017 after 28 years in service[50] with 11 have been sold to Skyline Aviation Group.[51]

The Royal Danish Navy (RDN) put the MH-60R on a short list for a requirement of around 12 new naval helicopters, together with the NH90/NFH, H-92, AW159 and AW101. The Request For Proposal was issued on 30 September 2010.[52] In November 2010, Denmark requested approval for a possible purchase of 12 MH-60Rs through a Foreign Military Sale.[53][54] In November 2012, Denmark selected 9 MH-60Rs to replace its 7 aging Lynx helicopters.[55] In October 2015, the US Navy accepted two mission ready MH-60R helicopters for Denmark.[56] In October 2018, Lockheed Martin was in the process of delivering the ninth and final MH-60R to Denmark.[57]

In July 2009, the Republic of Korea requested eight MH-60S helicopters, 16 GE T700-401C engines, and related sensor systems to be sold in a Foreign Military Sale.[58] However, South Korea instead chose the AW159 in January 2013.[59] In July 2010 Tunisia requested 12 refurbished SH-60Fs through a Foreign Military Sale.[60] But the change in government there in January 2011 may interfere with an order.[61]

In February 2011, India selected the S-70B over the NHIndustries NH90 for an acquisition of 16 multirole helicopters for the Indian Navy to replace its aging Westland Sea King fleet; the order includes an option for 44 additional helicopters.[62] India selected the Seahawk and confirmed procurement in November 2014.[63] In June 2017 however, India's Ministry of Defence had terminated the procurement program over a pricing issue.[64]

In 2011, Qatar requested a potential Foreign Military Sale of up to 6 MH-60R helicopters, engines and other associated equipment.[65] In late June 2012, Qatar requested another 22 Seahawks, 12 fitted with the armed helicopter modification kit and T700-401C engines with an option to purchase an additional six Seahawks and more engines.[66][67]

In 2011, Singapore bought six S-70Bs and then in 2013 ordered an additional two.[68]

In early 2015, Israel ordered eight ex-Navy SH-60Fs to support the expansion of the Israeli Navy surface fleet for ASW, ASuW and SAR roles.[69]

In 2015, Saudi Arabia requested the sale of ten MH-60R helicopters and associated equipment and support for the Royal Saudi Navy.[70][71]

In 2016, Malaysia is considering a purchase of new helicopters for its Royal Malaysian Navy, with the MH-60R Seahawk, AgustaWestland AW159 Wildcat, or the Airbus Helicopters H225M under evaluation for the role.[72]

In April 2018, the Defense Security Cooperation Agency announced it had received U.S. State Department approval and notified Congress of a possible sale to Mexican Navy of eight MH-60Rs, spare engines, and associated systems.[73][74] Mexico's president said that he plans to cancel the MH-60 sale to cut government spending.[75]

In August 2018, India's Defence Ministry approved the purchase of 24 MH-60R helicopters to replace their fleet of Westland Sea Kings.[76]

In April 2019, US approved sale of 24 anti-submarine hunter helicopters to India including spare parts for US$2.6 bn.[77] The Trump Administration notified the Congress that it has approved the sale of 24 MH-60R multi-mission helicopters, which will provide the Indian defence forces with the capability to perform anti-surface and anti-submarine warfare missions.[78]

Variants

U.S. versions

_members_sit_in_a_MH-60s_Knighthawk_helicopter_during_an_vertical_replenishment.jpg)

- YSH-60B Seahawk: Developmental version, led to SH-60B; five built.[79]

- SH-60B Seahawk: Anti-submarine warfare helicopter, equipped with an APS-124 search radar and an ALQ-142 ESM system under the nose, also fitted with a 25-tube sonobuoy launcher on the left side and modified landing gear; 181 built for the US Navy.

- NSH-60B Seahawk: Permanently configured for flight testing.[79]

- CH-60E: Proposed troop transport version for the U.S. Marine Corps. Not built.[80]

- SH-60F "Oceanhawk": Carrier-borne anti-submarine warfare helicopter, equipped with AQS-13F dipping sonar; 76 built for the U.S. Navy.[81]

- NSH-60F Seahawk: Modified SH-60F to support the VH-60N Cockpit Upgrade Program.[79]

- HH-60H "Rescue Hawk": Search-and-rescue helicopter for the U.S. Navy; 42 built.

- XSH-60J: Two U.S.-built pattern aircraft for Japan.

- SH-60J: Anti-submarine warfare helicopter for the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force.

- YSH-60R Seahawk:

- MH-60R Seahawk:

- YCH-60S "Knighthawk":

- MH-60S "Knighthawk":

- HH-60J/MH-60T Jayhawk: U.S. Coast Guard version. The HH-60J was developed with the HH-60H, the MH-60T is an upgrade to the HH-60J.

Export versions

- S-70B Seahawk: Sikorsky's designation for Seahawk. Designation is often used for exports.

- S-70B-1 Seahawk: Anti-submarine version for the Spanish Navy. The Seahawk is configured with the LAMPS (Light Airborne Multipurpose System)

- S-70B-2 Seahawk: Anti-submarine version for the Royal Australian Navy, similar to the SH-60B Seahawk in U.S. Navy operation.

- S-70B-3 Seahawk: Anti-submarine version for the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force. Also known as the SH-60J. The JMSDF ordered 101 units, with deliveries starting in 1991.

- S-70-4 Seahawk: Sikorsky's designation for the SH-60F Oceanhawk.

- S-70-5: Sikorsky's designation for the HH-60H Rescue Hawk and HH-60J Jayhawk.

- S-70B-6 Aegean Hawk: the Greek military variant which is a blend of the SH-60B and F models, based on Republic of China (Taiwan) Navy's S-70C(M)1/2.

- S-70B-7 Seahawk: Export version for the Royal Thai Navy.

- S-70B-28 Seahawk: Export version for Turkey.

- S-70C: Designation for civil variants of the H-60.

- S-70C(M)-1/2 Thunderhawk: Export version for the Republic of China (Taiwan) Navy, equipped with an undernose radar and a dipping sonar. The S-70C(M)-1 has the CT7-2D1 engines whereas S-70C(M)-2 is uprated with the T700-GE-401C turboshafts.

- S-70C-2: 24 radar-equipped UH-60 Black Hawks for China, the delivery of the helicopters was halted by an embargo.

- S-70C-6 Super Blue Hawk: Search-and-rescue helicopter for Taiwan, equipped with undernose radar, plus provision for four external fuel tanks on two sub wings.

- S-70C-14: VIP transport version for Brunei; two built.

- S-70A (N) Naval Hawk: Maritime variant that blends the S-70A Black Hawk and S-70B Seahawk designs.

- S-70L: Sikorsky's original designation for the SH-60B Seahawk.

Operators

.jpg)

- Royal Australian Navy – 24 MH-60R Seahawks in service as of March 2019[82][83][84]

- Brazilian Navy – 6 S-70B Seahawks in use with two more on order as of Dec. 2018.[85]

- Royal Danish Air Force – 7 MH-60R Seahawks as of Nov. 2019[86]

- Hellenic Navy – 11 S-70B6 Aegean Hawks in use as of Dec. 2018.[85] 4 MH-60R on order as of summer 2020.[87]

- Indian Navy (24 MH-60R Seahawks on order)[88]

- Israeli Navy (8 on order)[89][90]

.jpg)

- See SH-60J/K

- Republic of Korea Navy – 8 S-70/MH-60R/UH-60P as of Dec. 2018[85]

- Royal Saudi Navy – 1 MH-60R in use with 9 more on order as of Dec. 2018[85]

- Republic of Singapore Air Force – 8 S-70 Seahawks in service as of Dec. 2018[85]

- Spanish Navy – 14 SH-60B/Fs in service with 4 SH-60s remaining on order as of Dec. 2018[85]

_conduct_a_helicopter_in-flight_refueling_drill_with_an_MH-60R_Sea_Hawk_on_the_ship%E2%80%99s_flight_deck_in_the_Persian_Gulf.jpg)

- Republic of China Navy – 9 S-70C(M)-1 and 10 S-70C(M)-2 Thunderhawks in use as of Dec. 2018[85]

- Royal Thai Navy – 8 MH-60S Seahawks in operation as of Dec. 2018[85]

- Turkish Naval Forces – 24 S-70 Seahawks in use as of Dec. 2018[85]

- United States Navy – 526 HH/MH/SH-60 Seahawks in service as of Dec. 2018[85]

Specifications (SH-60B)

Data from Brassey's World Aircraft & Systems Directory,[91] Navy fact file, Sikorsky S-70B brochure[92] Sikorsky MH-60R brochure,[93], NATOPS FLIGHT MANUAL[94]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3–4

- Capacity: 5 passengers in cabin, slung load of 6,000 lb (2,700 kg) or internal load of 4,100 lb (1,900 kg) for B, F, and H models / 6,684 lb (3,032 kg) payload

- Length: 64 ft 8 in (19.71 m)

- Height: 17 ft 2 in (5.23 m)

- Empty weight: 15,200 lb (6,895 kg)

- Gross weight: 17,758 lb (8,055 kg) for ASW mission

- Max takeoff weight: 23,000 lb (10,433 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric T700-GE-401C turboshaft engines, 1,890 shp (1,410 kW) each for take-off

- Main rotor diameter: 53 ft 8 in (16.36 m)

- Main rotor area: 2,262.3 sq ft (210.17 m2)

- Blade section: root: SC1095/SC1095R8 ; tip: Sikorsky SC1095[95]

Performance

- Maximum speed: 146 kn (168 mph, 270 km/h)

- Never exceed speed: 180 kn (210 mph, 330 km/h)

- Range: 450 nmi (520 mi, 830 km)

- Service ceiling: 12,000 ft (3,700 m)

- Rate of climb: 1,650 ft/min (8.4 m/s)

Armament

- Up to two Mark 46 torpedoes or Mk 50 or Mk-54s or two 120 U.S. gal (454 L) fuel tanks for SH-60B and HH-60R and MH-60R

- AGM-114 Hellfire missile, 4 Hellfire missiles for SH-60B and HH-60H and MH-60R, 8 Hellfire missiles for MH-60S Block III.

- AGM-119 Penguin missile (being phased out),

- APKWS Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System,

- M60 machine gun or, M240 machine gun or GAU-16/A machine gun or GAU-17/A Minigun

- Rapid Airborne Mine Clearance System (RAMICS) using Mk 44 Mod 0 30 mm Cannon

See also

Related development

- Sikorsky S-70

- Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk

- Sikorsky HH-60 Pave Hawk

- Sikorsky HH-60 Jayhawk

- Mitsubishi H-60

- Piasecki X-49

- Sikorsky S-92/CH-148 Cyclone

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Boeing-Vertol YUH-61

- Eurocopter AS565 Panther

- Kaman SH-2G Super Seasprite

- Kamov Ka-27

- Harbin Z-20

- NHI NH90

- Westland Lynx

- AgustaWestland AW159 Wildcat

Related lists

- List of Sikorsky S-70 Models

- List of helicopters

- List of active United States military aircraft

References

Notes

- "MH-60R Seahawk total production".

- "MH-60S Knighthawk total production".

- "MH-60R Selected Acquisition Report (SAR)" (PDF). US Department of Defense. 31 December 2011. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- "MH-60S Selected Acquisition Report (SAR)" (PDF). US Department of Defense. 31 December 2011. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- Leoni 2007, pp. 203–4.

- Sikorsky S-70B Seahawk, Vectorsite.net, 1 July 2006.

- Eden, Paul. "Sikorsky H-60 Black Hawk/Seahawk", Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft, p. 431. Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- Leoni 2007, pp. 206–9.

- Mitsubishi (Sikorsky) SH-60J (Japan) Archived 2009-04-18 at the Wayback Machine. Jane's, 17 April 2007.

- "Mitsubishi SH-60K Upgrade". Jane's, 11 June 2008. Archived March 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Leoni 2007, p. 211.

- "Bureau (Serial) Numbers of Naval Aircraft" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-09. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- Donald 2004, p. 158.

- SH-60 Multipurpose Helicopter Archived 2010-06-12 at the Wayback Machine at Aerospaceweb.org

- Donald 2004, pp. 161–162.

- "MH-60R Seahawk - NAVAIR - U.S. Navy Naval Air Systems Command - Navy and Marine Corps Aviation Research, Development, Acquisition, Test and Evaluation". www.navair.navy.mil. Archived from the original on 2017-09-21. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- Donald 2004, p. 161.

- "MH-60R Seahawk Multimission Naval Helicopter". Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- "Telephonics to supply AN/APS-153 radars for US MH-60R aircraft". Naval Technology. 26 April 2012. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "MH-60R Equipment Guide". Military.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- "Navy chooses sensor datalink from L-3 Communications-West to help helicopters and warships share information". Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- "L3Harris to provide U.S. Navy with eight common datalink Hawklink AN/SRQ-4 systems for the MH-60R helicopter". Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- "AN/ARQ-59" (PDF). Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- Wendy Leland, ed. (November–December 2003). "Airscoop". Naval Aviation News. p. 8. Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2011-06-30 – via Naval History and Heritage Command. Search

- Donald 2004, pp. 159–160.

- Donald 2004, pp. 160–161.

- "MH-60S Knighthawk — Multi-Mission Naval Helicopter, USA". Naval Technology. Archived from the original on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- "Sikorsky SH-60 Seahawk helicopter, Fact File". Sikorsky. checked 2008-10-05 Archived September 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- LaGrone, Sam. "MH-60S underpowered for MCM towing operations, report finds." Jane's Information Group, 21 January 2013.

- U.S. Navy deploys its new Airborne Laser Mine Detection System (ALMDS) for the first time Archived 2014-09-14 at the Wayback Machine - Navyrecognition.com, 6 August 2014

- BAE Systems' Archerfish hunts down sea mines Archived 2016-04-18 at the Wayback Machine - Gizmag.com, 14 April 2016

- Donald 2004, pp. 156–157.

- Tomajczyk 2003, p. 55.

- Leoni 2007, p. 205.

- Helicopter Sea Combat Wing, Pacific Archived 2007-03-15 at the Wayback Machine. GlobalSecurity.org

- "MH-60R Helicopter Departs Lockheed Martin To Complete First Operational Navy Squadron" Archived 2008-08-15 at the Wayback Machine. Lockheed Martin, July 30, 2008.

- Sikorsky Delivers 400th MH-60 SEAHAWK Helicopter to U.S. Navy Archived 2013-08-01 at the Wayback Machine - Marketwatch.com, 23 July 2013

- Alford, Abbie (11 May 2015). "Navy retires the SH-60B Seahawk". San Diego: CBS 8. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- USS Gary Returns From Final Deployment; Also Last for SH-60B Seahawks Archived 2015-04-22 at the Wayback Machine - News.USNI.org, 20 April 2015

- Carrier Theodore Roosevelt returns from round-the-world deployment - Navytimes.com, 23 November 2015

- Leoni 2007, pp. 303–304.

- "Spain – Refurbishment of SH-60F Multi-Mission Utility Helicopters" Archived 2011-12-01 at the Wayback Machine. US Defense Security Cooperation Agency, 30 September 2010.

- "Spain seeks more Seahawk helicopters". Archived from the original on 2010-11-17. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- "Australia – MH-60R Multi-Mission Helicopters" Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine. US Defense Security Cooperation Agency, 9 July 2010.

- Archived 2011-06-17 at the Wayback Machine Australian Broadcasting Corporation Online, 16 June 2011

- "Australia requests US helicopters" Archived 2010-07-01 at the Wayback Machine. Rotothub, 29 April 2010.

- "MH-60R or NH90 NFH - Australia plans to buy 24 naval combat helicopters" Archived 2010-08-10 at the Wayback Machine. Defpro.com, 29 April 2010.

- "Final RAN Seahawk Romeo handed over". Australian Aviation. 12 September 2016. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Dominguez, Gabriel (1 December 2017). "RAN retires S-70B-2, AS350BA helicopters". IHS Jane's 360. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Skyline Aviation Group Acquired Australian Seahawks". Archived from the original on 2019-02-07. Retrieved 2019-02-06.

- Danish Request For Proposal Archived 2010-11-02 at the Wayback Machine. forsvaret.dk

- "Denmark – MH-60R Multi-Mission Helicopters" Archived 2010-12-14 at the Wayback Machine. US Defense Security Cooperation Agency, 30 November 2010.

- Hoyle, Craig. "Denmark requests Seahawk helicopter buy" Archived 2010-12-16 at the Wayback Machine. Flight Global, 13 December 2010. Retrieved: 14 December 2010.

- Hoyle, Craig. "Denmark confirms MH-60R selection to replace Lynx helicopters" Archived 2012-11-30 at the Wayback Machine. Flight Global, 21 November 2012. Retrieved: 21 November 2012.

- "MH-60R Denmark Delivery". Archived from the original on 2017-09-21. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- Tringham, Kate (23 October 2018). "Euronaval 2018: Lockheed Martin prepares to deliver final Danish MH-60R helicopter, eyes future markets". IHS Jane's 360. Paris. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- "Korea – MH-60S Multi-Mission Helicopters" Archived 2009-08-06 at the Wayback Machine. US Defense Security Cooperation Agency, 22 July 2009.

- "South Korea picks AW159 for maritime helicopter deal" Archived 2013-01-20 at the Wayback Machine. Flight International, 15 January 2013.

- "Tunisia – Refurbishment of Twelve SH-60F Multi-Mission Helicopters" Archived 2010-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. US Defense Security Cooperation Agency, 2 July 2010.

- "SH-60F Seahawk Helis for Tunisia". Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "India to go for open bidding for Navy deal, rejects US offer" Archived 2011-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. Economic Times, 18 February 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-09-12. Retrieved 2014-11-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bedi, Rahul (15 June 2017). "India scraps planned acquisition of S-70B Seahawk helos". IHS Jane's 360. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-10-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Qatar – MH-60R and MH-60S Multi-Mission Helicopters" Archived 2012-07-22 at the Wayback Machine. US Defense Security Cooperation Agency, 28 June 2012.

- Sambridge, Andy (30 June 2012). "Qatar keen on $2.5bn US helicopters deal". ArabianBusiness.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- Waldron, Gregg (February 20, 2013). "Singapore orders two additional S-70B helicopters". Flight Global. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- "צפו: המסוק החדש של חיל הים מפגין ביצועים". 18 February 2015. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – MH-60R Multi-Mission Helicopters". www.defense-aerospace.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – MH-60R Multi-Mission Helicopters - The Official Home of the Defense Security Cooperation Agency". www.dsca.mil. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- "AW-159 – Asian Navies Evaluate Acquisition of ASW Helicopters". Defense Update. 23 February 2016. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "US State Department approves sale of MH-60R helicopters to Mexico". navaltoday.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-03. Retrieved 2018-05-02.

- "Mexico – MH-60R Multi-Mission Helicopters". US DSCA. 19 April 2018. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-07-20. Retrieved 2018-07-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Raghuvanshi, Vivek. India is one step closer to spending billions on new naval helicopters from US, allies. Defense News, 2018-08-27

- "India – MH-60R Multi-Mission Helicopters | the Official Home of the Defense Security Cooperation Agency". Archived from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- "US approves sale of anti-submarine hunter helicopters to India for USD 2.4 bn". 2019-04-03. Archived from the original on 2019-04-03. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- DoD 4120-15L, Model Designation of Military Aerospace Vehicles Archived 2007-10-25 at the Wayback Machine. US DoD, 12 May 2004.

- Donald, David, ed. "Sikorsky S-70". The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft. Barnes & Noble Books, 1997. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- "S-60B (SH-60B Seahawk, SH-60F CV, HH-60H Rescue Hawk, HH-60J Jayhawk, VH-60N)". Igor I Sikorsky Historical Archives. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- "Sikorsky MH-60R Seahawk". navy.gov.au. Royal Australian Navy. Archived from the original on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- "Lockheed Martin hands over RAN's final Romeo". Australian Aviation. 2016-07-28. Archived from the original on 2019-05-25. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Yeo, Mike (2019-03-06). "Australian Navy gets more out of the Seahawk helicopter than originally planned". Defense News. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- Hoyle, Craig (4 December 2018). "ANALYSIS: 2019 World Air Forces Directory". Flight Global. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- "Om Helicopter Wing Karup". Royal Danish Air Force. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- https://www.ptisidiastima.com/greece-signed-2-loa-for-4-mh60r-and-s70-modernization/

- "The US State Department has cleared the sale of 24 Lockheed Martin MH-60R". Flight Global. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- "Israel finalises Seahawk sensor configuration". Flight Global. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 26 May 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- "Israel – Excess SH-60F Sea-Hawk Helicopter Equipment and Support". Defense Security Cooperation Agency. 6 July 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 2019-04-14.

- Taylor, M J H, ed. (1999). Brassey's World Aircraft & Systems Directory 1999/2000 Edition. Brassey's. ISBN 1-85753-245-7.

- "S-70B Seahawk Mission Brochure" (PDF). Sikorsky.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2013.

- "MH-60R brochure" (PDF). lockheedmartin.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2018.

- "NATOPS FLIGHT MANUAL: NAVY MODEL SH-60B HELICOPTER" (PDF). info.publicintelligence.net. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-30. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- A1-H60CA-NFM-000 NATOPS Flight Manual Navy Model H-60F/H Aircraft

- Donald, David ed. "Sikorsky HH/MH/SH-60 Seahawk". Warplanes of the Fleet. AIRtime, 2004. ISBN 1-880588-81-1.

- Leoni, Ray D. Black Hawk, The Story of a World Class Helicopter. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2007. ISBN 978-1-56347-918-2.

- Tomajczyk, Stephen F. Black Hawk. MBI, 2003. ISBN 0-7603-1591-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |