1963 24 Hours of Le Mans

The 1963 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 31st Grand Prix of Endurance in the 24 Hours of Le Mans series and took place on 15 and 16 June 1963. It was also the tenth round of the 1963 World Sportscar Championship season.

| 1963 24 Hours of Le Mans | |

| Previous: 1962 | Next: 1964 |

| Index: Races | Winners | |

Despite good weather throughout the race, attrition was high, leaving only twelve classified finishers. There were a number of major accidents, the most serious of which caused the death of Brazilian driver Christian Heins and bad injuries to Roy Salvadori and Jean-Pierre Manzon. This was the first win for a mid- or rear-engined car, and the first all-Italian victory – with F1 drivers Ludovico Scarfiotti and Lorenzo Bandini winning in their Ferrari 250 P. In fact, Ferrari dominated the results list filling the first six places, and the winners’ margin of over 200 km (16 laps) was the biggest since 1927.

Regulations

In 1963 the CSI (Commission Sportive Internationale - the FIA’s regulatory body) lifted the 4.0 litre engine restriction on its GT classes, as well as introducing a sliding scale for minimum weight versus engine size. That change again opened the field to large American V8s, used on the AC Cobras and Lola Mk6 that year. It also revised the equivalence ratio for forced induction/turbo engines from 1.2 up to 1.4. The minimum height for cars was increased to 850mm (33.5 inches).[1]

The Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) renamed its ‘Experimental’ category as ‘Prototype’ and lifted the 4.0 litre engine restriction for those classes as well. The main change for the race was the starting positions on the grid were determined by the fastest times in practice rather than in order of engine size.[1][2] In a nod to driver safety, the wearing of safety-belts was now recommended.[3]

Entries

The ACO received 80 entries but after a number of withdrawals there were 55 cars to practice. The proposed entry list comprised:

| Category | Classes | Prototype Entries |

GT Entries |

Total Entries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large-engines | 3.0+, 3.0, 2.5L | 14 | 13 | 27 |

| Medium-engines | 2.0, 1.6, 1.3L | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| Small-engines | 1.15, 1.0, 0.85L | 15 (+2 reserves) | 0 | 15 |

| Total Cars | 31 (+2 reserves) | 23 | 54 (+1 experimental) |

Once again Ferraris easily dominated the entry list with eleven cars. SEFAC Ferrari brought three new prototypes. The 250 P was an innovative mid-engined design of Mauro Forghieri that was a longer version of the Dino. The hefty 3-litre V12 generated 310 bhp.[4] The team's regular Formula 1 drivers were assigned: John Surtees with Willy Mairesse, and Ludovico Scarfiotti with Lorenzo Bandini. The third car was driven by sports-car regulars Mike Parkes and Umberto Maglioli

There were also three new 330 LMB 4-litre front-engined prototypes run by privateer teams. While Ferrari stalwart Pierre Noblet ran a works-supported entry, the North American Racing Team (NART) ran another (for Dan Gurney and Jim Hall) as well as the 330 TRI/LM, for Pedro Rodriguez and Roger Penske, that had won the race the previous year.[5] There was also a new British team – Ronnie Hoare's Maranello Concessionaires entered a 330 LMB for Jack Sears and Mike Salmon.[6]

Four manufacturers lined up against the big Ferrari prototypes: Aston Martin, Maserati, Lister and Lola. John Wyer had convinced the ACO to accept the Aston Martin DP214 prototypes as GT-derivatives of the DB4 cars. The successor DP215 had a new 4.0-litre engine capable of 323 bhp. It was driven by Phil Hill and Lucien Bianchi.[7]

Maserati returned with an updated Tipo 151 coupé for their French agency. Lightened and now fitted with a fuel-injected 5-litre V8 engine, it was the biggest car in the field and produced an impressive 430 bhp capable of 290 kp/h (180 mph). It would be raced by French veteran André Simon and Lloyd ‘Lucky’ Casner (owner of the American Camoradi team racing Maserati cars).[8]

For their second foray into Le Mans, Lola rushed their revolutionary Mk6 GT prototype. The Eric Broadley / Tony Southgate design had a steel monocoque chassis with fibreglass body and intricate suspension design. Initially fitted with a mid-mounted Ford 4.2-litre Indycar engine generated 350 bhp, it was subsequently uprated to the 4.7 litre Ford engine. The car was so light that it needed ballast to reach its 875 kg minimum weight. However it was undergeared and could only reach a maximum 240 kp/h (150 mph).[9] The car would be raced by David Hobbs and debutante Richard Attwood

Porsche, now entered as Porsche System Engineering, a Swiss-registered entity for the works team, had the 2-litre class to itself. They arrived with a pair of developed 718-series cars that had won the Targa Florio when the Ferrari s had failed. One a coupé (for ‘Jo’ Bonnier/Tony Maggs), the other a spyder (for Edgar Barth/Herbert Linge), they used the new 2-litre Flat-8 Formula 1 engine.[10]

Once again the smaller-engined classes were strongly contested. Charles Deutsch (last year's victor), after the withdrawal of Panhard's engines, signed a deal with German manufacturer Auto Union-DKW. The 750cc three-cylinder, two-stroke engine could develop 80 bhp and with the streamlined body, could reach 225 kp/h (140 mph).[11] His erstwhile partner, Bonnet had four works entries. Their new streamlined version now named the “Aerodjet”.[3] Their French opposition however was from a new team: Jean Rédélé's new Alpine marque (also running with 1-litre Renault engines). The new A110 came to Le Mans in its streamlined M63 longtail version.

Austin-Healey had a new body designed by Frank Costin for their Sebring Sprite. The 1100cc BMC engine developed 95 bhp.[12] Another British boutique sports-car manufacturer, Deep Sanderson, arrived with its new 301 prototype.

Since 1953 the ACO had offered a prize for a turbine-drive car to complete the 24-hour event. Yet it was only this year that a formal entry was received. Rover had worked on turbines for twenty years and the previous year their fourth prototype had done demonstration laps at Le Mans. Based on a BRM Formula 1 car, the twin turbines generated 150 bhp but only gave a maximum speed of 230 kp/h (145 mph). Unable to run on regulation fuel, (it ran on paraffin) the car was not on the official entry list, and given number “00”. And without a heat exchanger, the turbine's fuel consumption was so great (7mpg) that it could not run with a regulation fuel-tank.[13] BRM, in turn, released their grand prix drivers, Richie Ginther and current World Champion Graham Hill.[14][3]

In the GT division there were four Ferrari 250 GTOs. The works car was driven by sports-car regulars Carlo Maria Abate and Fernand Tavano. The two Belgian teams, Ecurie Francorchamps and Equipe Nationale Belge, returned and NART ran a long-wheelbase version.

Aston Martin had got two of their DP214 cars homologated, running with the same 3.7-litre engine as the DB4. The works team had Grand Prix drivers Bruce McLaren and Innes Ireland in one and Bill Kimberly / Jo Schlesser in the second. Jean Kerguen also returned with his French Aston Martin for the third year.

Briggs Cunningham was back this year with three of the Jaguar E-type ‘Lightweight’ specials overseen by Lofty England. The fuel-injected 3.8-litre Straight-6 engine now developed 310 bhp. Cunningham drove with Bob Grossman with his other regular drivers Walt Hansgen and Roy Salvadori were paired with Augie Pabst and Paul Richards respectively.[15]

After his success in winning the 1959 race, Carroll Shelby had been working with Derek Hurlock, owner of AC Cars, to fit the new 260cu in (4.2-litre) small-block Ford V8 to the AC Ace chassis that was already race-proven at Le Mans. Put into production, it was the Mk 2 version with the bigger 289cu in (4.7-litre) Ford Windsor engine that was entered for the race. One from AC Cars for Ninian Sanderson and Peter Bolton, was managed by Stirling Moss and the other from Ed Hugus, who had run the car's race development in America.[16]

In the smaller categories the Porsche works team had a pair 356B GS for their regular Dutch drivers Carel Godin de Beaufort and Ben Pon. The cars were now fitted with a new 2.0-litre flat-4 engine.[10] They would be up against a privateer MG MGB, the manufacturer's latest model, driven by top British rally driver Paddy Hopkirk.[17] In the 1600cc class a pair of works Sunbeam Alpines were matched against three Alfa Romeos run by the teams Scuderia Sant Ambroeus and Scuderia Filipinetti. The two Team Elite Lotuses had the 1300cc to themselves when the Equipe Nationale Belge Elite entry was withdrawn.

Practice

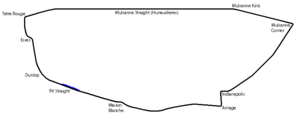

Twenty-three cars availed themselves of the testing weekend over 6–7 April. It was the first appearance of the Ferrari 330 LMB and in it works driver Mike Parkes became the first driver to officially break 300 kp/h (186 mph) on the long Mulsanne Straight. But it was John Surtees who put in the best time over the weekend, with a blistering 3 min 45.8 s.[6][2] Later, in official qualifying, Phil Hill was also calculated to have hit that magical 300kp/h barrier on the Mulsanne in his Aston Martin prototype.[7]

Rushing to have their Lola GTs ready in time, Eric Broadley drove the first car himself across from their Bromley factory. Although arriving after inspections had officially closed, the ACO, perhaps surprisingly, still allowed the car to enter. The second car, still unassembled, had to be scratched).[9][2]

Further late withdrawals and no-shows left only 49 cars to practice. The honour of the first Pole Position by qualification went to Pedro Rodriguez in the NART Ferrari with a lap-time of 3 min 50.9 s on Wednesday night.[2] The works Ferrari 250s were second and third (Bandini ahead of Parkes). In fact all eleven Ferraris qualified in the top sixteen places. Hill got his Aston Martin to 4th, with his teammates in 8th and 10th, while the big Maserati was 6th on the grid.

Jo Bonnier got his two-litre Porsche in a very credible 17thwith a 4 min 07.9 s, well ahead of his nearest competition – his teammates in 23rd (4 min 13.2 s) and the GT Porsche in 26th with a distant 4 min 35.8 . The fastest of the small cars was the Alpine of Richard/Frescobaldi with 4 min 42.8 s (29th). The Rover turbine did a 4 min 22.0 s that would have qualified it mid-field, but being outside the field it had to start 30 seconds after flagfall at the back of the field.[14][2]

Race

Start

It was a sunny start for the race at 4 pm. Phil Hill got his Aston Martin off the line first, ahead of the Ferraris. But it was the Frenchman André Simon in his Maserati who delighted the local crowd. He blasted past them, nudging Surtees out the way at Mulsanne then overtaking Hill before Arnage to lead the first lap.[5] Pat Ferguson planted his Lotus Elite into the sandbank at Mulsanne on the first lap, although he eventually managed to extricate it (only to plant it back in exactly the same spot on his next lap!).[18][19] On the second lap André Guilhaudin, owner-driver of the CD-DKW, crashed it at Indianapolis, but his damage was terminal.[11] Then on only the fifth lap, as the leaders were lapping the tail-enders, Roger Masson's Bonnet clipped the verge on the brow after the Dunlop bridge. It spectacularly somersaulted twice but Masson got out unharmed.[6] Both Phil Hill, now running fourth, and Peter Sargent's Lister hit debris and damaged their gearboxes trying to slow but were able to keep on running. Simon continued to lead throughout his opening 2-hour stint before handing over to his co-driver ‘Lucky’ Casner. However, only an hour into his race, Casner brought the Maserati in with terminal gearbox problems.[8] Likewise the earlier stress on the Hill Aston Martin and Sargent Lister took its toll and they too retired early with broken transmissions.[7][20]

Ferraris now assumed the top five positions. At the 4-hour mark the works 250s of Surtees/Mairesse and Parkes/Maglioli were ahead of the NART 330 TRI/LM then Scarfiotti/Bandini in the other 250 P and Noblet's privateer 330. Sixth place was Bruce McLaren in his Aston Martin, leading the GT category. However at 8.20pm, a piston shattered in the engine while he was at speed going into the Mulsanne kink.[21] McLaren managed to get the car safely to the roadside but the long oil slick from the holed sump started a catastrophic chain reaction of accidents: Jean Kerguen's DB4 Aston Martin spun out into a ditch, wrecking its differential. Sanderson endured a series of spins in his Cobra but luckily hit nothing and carried on.[16] Then Salvadori's Jaguar arrived and spun at 265 kp/h (165 mph) and crashed into the banking. Fortunately, Salvadori (who had been unable to do up his full harness) was thrown out the rear window as the car burst into flames, then helped by Kerguen.[21][15] This was then hit by Jean-Pierre Manzon's little Bonnet which rebounded into the middle of the track. Manzon, son of the great French racer Robert Manzon, was seriously injured and thrown onto the track. Christian Heins, leading his class and the Index of Performance, managed to avoid Manzon and the wrecks but in doing so, his Alpine-Renault went out of control, rolled and hit a lamp-post then exploded into flames. ‘Bino’ Heins, whose Willys franchise built the Alpines in Brazil, was killed instantly.[22][7][21][23]

Night

As night fell, Ferrari's fortunes began to change: the Noblet/Guichet car had to retire after a Ferrari mechanic forgot to replace the oil filler cap.[6] Then Parkes and Maglioli were delayed, losing ten laps, to change the distributor.[4][24] Carlo Abate, in the works-run GTO, was running third just about midnight when he got off-line going through the tricky Maison Blanche corner. He crashed at speed, wrecking the car, but was not injured.[25] Not so fortunate was Bob Olthoff who crashed his Sebring Sprite there soon afterward and was taken to hospital with a broken collarbone.[12]

Through the night Surtees and Mairesse continued to build their lead over their teammates. The NART Ferrari had charged back up to third after being delayed. However around 2am an oil-line burst and destroyed Penske's engine. Jo Bonnier, whose Porsche was running 7th and leading the medium-sized classes, came through the huge plume of engine smoke unsighted and crashed heavily in the trees. Bonnier was lucky to get away uninjured.[22][10]

An hour later, the Gurney/Hall NART Ferrari, now running third, suddenly slowed at Maison Blanche. Hall coasted towards the pits then pushed it the final distance only to be told that the half-shaft had broken.[6] The Kimberly/Schlesser Aston Martin inherited the place but the curse of third struck again soon before 2am, when they were forced to retire with piston problems, ending Aston Martin's challenge.[7][24]

By the halfway mark at 4am, there were only 21 cars left running. However, Ferrari had the numbers to outlast their opposition. Surtees/Mairesse had done 189 laps, with a lap's lead over Scarfiotti/Bandini. The works cars already had a massive 10-lap lead over the remaining NART Ferrari of Gregory/Piper, the two Belgian GTOs. Sixth was the Barth/Linge Porsche 718 moving past the Maranello Ferrari and Cunningham's Jaguar, with the Parkes’ Ferrari charging back up the field in 9th. The Rover was cruising quietly just outside the top-10[21]

Morning

As dawn broke among the rising mist, David Hobbs in the Lola had a big accident at Maison Blanche. After running as high as 8th, the team had been battling the gearbox most of the night, losing two hours in the pits. Hobbs had been trying to change down for the corner when the gearbox finally jammed.[9] A few hours later the leading Porsche of Barth/Linge, now up to 5th, lost a rear wheel coming up to the main straight. Edgar Barth pushed it the half kilometre to the pits where it was repaired and carried on.[10][21]

Briggs Cunningham and Bob Grossman had steadily moved their Lightweight Jaguar into the top-10 through the night. However, on Sunday morning the brake pedal snapped as Grossman came to the end of the Mulsanne straight. The car slammed through three rows of haybales, scattering spectators, but he was able to get the car back to the pits.[26] Stealing parts from their third car that had retired in the first hour, they lost two hours but got back into the race.[15][21]

After leading for fifteen hours, Surtees and Mairesse had built up a two-lap lead. However at 10.45 Surtees pitted for fuel and a driver change. Mairesse got no further than the Esses when the car burst into flames. Fuel had carelessly been spilt in the engine bay and an electrics spark applying the brake lights ignited it. Mairesse got out, overalls on fire, before the car came to a halt. The mild burns to his face and arms kept him out of racing for two months.[4]

Their teammates Scarfiotti and Bandini moved up to take the lead they wouldn’t cede.[22]

Finish and post-race

In the end they won easily – by 16 laps. In a record distance, it was the widest winning margin since Bentley's epic 1927 win (350 km).[3] With Scarfiotti, Bandini and Ferrari it was the first all-Italian victory, as well as being the first win for a mid- or rear-engined car. In a dominant display Ferrari took the top six places. The Scuderia shared the top places with the two Belgian GT teams racing each other: Parkes and Maglioli chased hard and only failed to catch the Equipe Nationale Belge GTO, in second, by just over 100 metres.[22] Fourth was the Ecurie Francorchamps GTO barely a lap behind. The Belgian drivers all celebrated together by driving to Paris two days later, and going to a nightclub till 4am leaving their respective racing cars parked outside.[25]

The Maranello team's Ferrari came in 5th after battling overheating issues for most of the race.[6][24] Sixth, and last surviving Ferrari, was the NART 250 GTO/LMB of Gregory and Piper. It had been out of alignment since 8am when Gregory had gone off at Arnage taking an hour to dig it out of the sand-trap.[25]

After a remarkably trouble-free run (needing no mechanical work or even a change of tyres), the Rover turbine easily exceeded its 3600 km minimum distance (an average of 150 km/h) and was awarded the ACO's FF25000 prize. Although not classified, it covered sufficient distance that it would have finished 7thand beaten the 1958 winning car.[14][3][27] In fact, classified 7th was the Sanderson/Bolton AC Cobra

After their troubles, the Barth/Linge Porsche came in 8th and Cunningham's Jaguar came in 9th. After the race-start antics the Lotus Elite of Ferguson and Wagstaff, finished tenth and class-winner.

Despite the good weather, attrition was high and the number of major accidents meant there were only fourteen cars running at the end of the 49 starters. The sole surviving Bonnet won the Index of Thermal Efficiency, driven by Claude Bobrowski and young debutante motorcyclist Jean-Pierre Beltoise

Official results

Finishers

Results taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO[28] Class Winners are in Bold text.

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P 3.0 |

21 | Ferrari 250 P | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 339 | ||

| 2 | GT 3.0 |

24 | Ferrari 250 GTO | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 323 | ||

| 3 | P 3.0 |

22 | Ferrari 250 P | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 323 | ||

| 4 | GT 3.0 |

25 | Ferrari 250 GTO | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 322 | ||

| 5 | P +3.0 |

12 | Ferrari 330 LMB | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 314 | ||

| 6 | GT 3.0 |

26 | Ferrari 250 GTO/LMB | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 312 | ||

| N/C * | Exp | 00 | Rover-BRM | Rover Turbine | 310 | ||

| 7 | GT +3.0 |

3 | AC Cobra Hardtop | Ford 4.7L V8 | 310 | ||

| 8 | P 2.0 |

28 | Porsche 718/8 W-RS Spyder | Porsche 1962cc F8 | 300 | ||

| 9 | GT +3.0 |

15 | Jaguar E-Type Lightweight | Jaguar 3.8L S6 | 283 | ||

| 10 | GT 1.3 |

39 | Lotus Elite Mk14 | Coventry Climax 1216cc S4 | 270 | ||

| 11 | P 1.15 |

53 | Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Renault-Gordini 1108cc S4 | 269 | ||

| 12 | GT 2.0 |

31 | (private entrant) |

MG MGB Hardtop | BMC 1803cc S4 | 264 | |

| N/C** | P 1.15 |

41 | Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Renault-Gordini 1108cc S4 | 211 |

- Note *: Not Classified as car was in Experimental class.

- Note **: Not Classified because Insufficient distance covered.

Did Not Finish

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNF | P 3.0 |

23 | Ferrari 250 P | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 252 | fuel spill / fire (19hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.0 |

50 | Alpine A110 M63 | Renault-Gordini 996cc S4 | 227 | conrod (23hr) | ||

| DNF | GT 1.6 |

32 | Sunbeam Alpine | Sunbeam 1592cc S4 | 200 | engine (19hr) | ||

| DNF | GT 1.3 |

38 | Lotus Elite Mk14 | Coventry Climax 1216cc S4 | 167 | engine (16hr) | ||

| DNF | GT 1.6 |

34 | Alfa Romeo Giulietta SZ | Alfa Romeo 1570cc S4 | 155 | gearbox (16hr) | ||

| DNF | P +3.0 |

6 | Lola Mk6 GT | Ford 4.7L V8 | 151 | accident (15hr) | ||

| DNF | P +3.0 |

7 | Aston Martin DP214 | Aston Martin 3.7L S6 | 139 | piston (11hr) | ||

| DNF | P +3.0 |

11 | Ferrari 330 LMB | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 126 | gearbox (10hr) | ||

| DSQ | GT +3.0 |

4 | (private entrant) |

AC Cobra Coupé | Ford 4.7L V8 | 117 | premature oilchange (10hr) | |

| DNF | GT 2.0 |

30 | Porsche 356B GS | Porsche 1967cc F4 | 115 | engine (10hr) | ||

| DNF | P +3.0 |

10 | Ferrari 330 TRI/LM | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 113 | oil line (9hr) | ||

| DSQ | P 1.0 |

44 | Deep Sanderson 301 | BMC 997cc S4 | 110 | insufficient distance (15hr) | ||

| DNF | P 3.0 |

27 | Porsche 718/8 GTR Coupé | Porsche 1981cc F8 | 109 | accident (9hr) | ||

| DNF | GT 3.0 |

20 | Ferrari 250 GTO | Ferrari 3.0L V12 | 105 | accident (9hr) | ||

| DSQ | P 1.0 |

58 | (private entrant) |

Abarth 850 | Fiat 847cc S4 | 96 | premature refuel (12hr) | |

| DNF | GT 2.0 |

29 | Porsche 356B GS | Porsche 1967cc F4 | 94 | engine (8hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.15 |

42 | Austin-Healey Sebring Sprite | BMC 1101cc S4 | 94 | accident (9hr) | ||

| DNF | GT 1.6 |

33 | Sunbeam Alpine | Sunbeam 1592cc S4 | 93 | head gasket (13hr) | ||

| DNF | P +3.0 |

9 | (private entrant) |

Ferrari 330 LMB | Ferrari 4.0L V12 | 79 | oil pipe (8hr) | |

| DSQ | GT 1.6 |

35 | Alfa Romeo Giulietta SZ | Alfa Romeo 1570cc S4 | 70 | premature oilchange (7hr) | ||

| DNF | GT +3.0 |

19 | (private entrant) |

Aston Martin DB4 GT Zagato | Aston Martin 3.7L S6 | 65 | accident / rear axle (7hr) | |

| DNF | P 1.0 |

49 | Alpine A110 M63 | Renault-Gordini 996cc S4 | 63 | clutch (8hr) | ||

| DNF | GT +3.0 |

8 | Aston Martin DP214 | Aston Martin 3.7L S6 | 59 | piston (6hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.0 |

48 | Alpine A110 M63 | Renault-Gordini 996cc S4 | 50 | fatal accident (6hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.0 |

52 | Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Renault-Gordini 996cc S4 | 47 | accident (6hr) | ||

| DNF | P +3.0 |

2 | Maserati Tipo 151/3 Coupé | Maserati 4.9L V8 | 40 | gearbox (4hr) | ||

| DNF | GT +3.0 |

16 | Jaguar E-Type Lightweight | Jaguar 3.8L S6 | 40 | accident (6hr) | ||

| DNF | P +3.0 |

17 | (private entrant) |

Lister Costin Coupe | Jaguar 3.8L S6 | 29 | engine (4hr) | |

| DNF | P +3.0 |

18 | Aston Martin DP215 | Aston Martin 4.0L S6 | 29 | gearbox (4hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.0 |

54 | Bonnet RB5 | Renault 716cc S4 | 25 | out of fuel (3hr) | ||

| DNF | GT +3.0 |

14 | Jaguar E-Type Lightweight | Jaguar 3.8L S6 | 8 | gearbox (1hr) | ||

| DNF | GT 1.6 |

36 | Alfa Romeo Giulietta GZ | Alfa Romeo 1570cc S4 | 7 | valve gear (2hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.0 |

51 | Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Renault-Gordini 996cc S4 | 4 | accident (1hr) | ||

| DNF | P 1.0 |

55 | (private entrant) |

Abarth 1000 SP | Fiat 998cc S4 | 3 | engine (1hr) | |

| DNF | P 1.0 |

56 | CD-DKW Coupé | DKW 750cc S3 (2-Stroke) |

1 | accident (1hr) |

Did Not Practise

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNP | GT +3.0 |

1 | (private entrant) |

Chevrolet Corvette (C2) | Chevrolet 5.4L V8 | did not arrive | |

| DNP | GT +3.0 |

5 | Lola Mk6 GT | Ford 4.7L V8 | did not arrive in time | ||

| DNP | GT 1.3 |

40 | Lotus Elite Mk14 | Coventry Climax 1216cc S4 | did not arrive | ||

| DNP | P 1.0 |

44 | Deep Sanderson 301 | BMC 997cc S4 | did not arrive | ||

| DNP | P 1.15 |

43 | ASA 1000 GT | ASA 1032cc S4 | did not arrive | ||

| DNP | P 1.0 |

46 | ASA 1000 GT | ASA 996cc S4 | did not arrive | ||

| DNP | P 1.0 |

47 | ASA 1000 GT | ASA 996cc S4 | did not arrive |

Class Winners

| Class | Prototype Winners | Class | GT Winners | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prototype >3000 |

#12 Ferrari 330 LMB | Salmon / Sears | Grand Touring >3000 |

#3 AC Cobra | Sanderson / Bolton |

| Prototype 3000 |

#21 Ferrari 250 P | Scarfiotti / Bandini | Grand Touring 3000 |

#24 Ferrari 250 GTO | “Beurlys”/ van Ophem |

| Prototype 2500 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 2500 |

no entrants | ||

| Prototype 2000 |

#28 Porsche 718/8 Spyder | Barth / Linge | Grand Touring 2000 |

#31 MGB | Hutcheson / Hopkirk |

| Prototype 1600 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 1600 |

no finishers | ||

| Prototype 1300 |

no entrants | Grand Touring 1300 |

#39 Lotus Elite | Ferguson / Wagstaff | |

| Prototype 1150 |

#53 Bonnet Aérodjet LM6 | Bobrowski / Beltoise | Grand Touring 1150 |

no entrants | |

| Prototype 1000 |

no finishers | Grand Touring 1000 |

no entrants | ||

Index of Thermal Efficiency

- Note: Only the top ten positions are included in this set of standings.

Index of Performance

Taken from Moity's book, at odds with Quentin Spurring's book.[29]

- Note: Only the top ten positions are included in this set of standings. A score of 1.00 means meeting the minimum distance for the car, and a higher score is exceeding the nominal target distance.

Statistics

Taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO

Challenge Mondial de Vitesse et Endurance Standings

| Pos | Manufacturer | Points |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 39 | |

| 2 | 35 | |

| 3 | 22 | |

| 4 | 10 |

- Citations

- Spurring 2010, p.108

- Clarke 2009, p.117: Motor Jun16 1963

- Moity 1974, p.95

- Spurring 2010, p.110

- Spurring 2010, p.107

- Spurring 2010, p.115

- Spurring 2010, p.119

- Spurring 2010, p.120

- Spurring 2010, p.116

- Spurring 2010, p.117

- Spurring 2010, p.125

- Spurring 2010, p.131

- Clausager 1982, p.126

- Spurring 2010, p.112-113

- Spurring 2010, p.121

- Spurring 2010, p.128

- Spurring 2010, p.130

- Spurring 2010, p.127

- Armstrong 1964, p.146

- Clarke 2009, p.118: Motor Jun16 1963

- Clarke 2009, p.114-5: Road & Track Sep 1963

- Spurring 2010, p.109

- Peralta, Pablo Robert. "Christian Heins". historicracing.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05.

- Clarke 2009, p.119-20: Motor Jun16 1963

- Spurring 2010, p.124

- Armstrong 1964, p.152

- Armstrong 1964, p.142

- Spurring 2010, p.2

- Moity 1974, p.170

- Moity 1974, p.92

References

- Armstrong, Douglas – English editor (1964) Automobile Year #11 1963-64 Lausanne: Edita S.A.

- Clarke, R.M. - editor (2009) Le Mans 'The Ferrari Years 1958-1965' Cobham, Surrey: Brooklands Books ISBN 1-85520-372-3

- Clausager, Anders (1982) Le Mans London: Arthur Barker Ltd ISBN 0-213-16846-4

- Laban, Brian (2001) Le Mans 24 Hours London: Virgin Books ISBN 1-85227-971-0

- Moity, Christian (1974) The Le Mans 24 Hour Race 1949-1973 Radnor, Pennsylvania: Chilton Book Co ISBN 0-8019-6290-0

- Spurring, Quentin (2010) Le Mans 1960-69 Yeovil, Somerset: Haynes Publishing ISBN 978-1-84425-584-9

External links

- Racing Sports Cars – Le Mans 24 Hours 1962 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 14 December 2017

- Le Mans History – Le Mans History, hour-by-hour (incl. pictures, YouTube links). Retrieved 14 December 2017

- Sportscars.tv – race commentary. Retrieved 14 December 2017

- World Sports Racing Prototypes – results, reserve entries & chassis numbers. Retrieved 14 December 2017

- Team Dan – results & reserve entries, explaining driver listings. Retrieved 14 December 2017

- Unique Cars & Parts – results & reserve entries. Retrieved 14 December 2017

- Formula 2 – Le Mans 1963 results & reserve entries. Retrieved 15 December 2017

- Motorsport Memorial – article about Christian Heins. Retrieved 24 January 2018

- YouTube – remastered, short British Pathé clip in colour (8 min). Retrieved 14 December 2017

- YouTube – 4x 10min silent, colour clips from British Pathé of out-takes for anorther film. Retrieved 14 December 2017

- YouTube – personal camera footage, silent, in colour (5 mins). Retrieved 14 December 2017