Chevrolet Corvette (C2)

The Chevrolet Corvette (C2) is the second generation of the Chevrolet Corvette sports car, produced by the Chevrolet division of General Motors for the 1963 to 1967 model years.[7]

| Chevrolet Corvette (C2) | |

|---|---|

1964 Chevrolet Corvette Convertible | |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | The Chevrolet Division of General Motors |

| Also called |

|

| Production | August 1962–July 1967[1][2] |

| Model years | 1963–1967 |

| Assembly | United States: St. Louis, Missouri |

| Designer | Larry Shinoda (1959, 1960)[3] |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Sports car |

| Body style |

|

| Layout | FMR layout |

| Related | Duntov LightWeight[4] Superformance Corvette Grand Sport[5] |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine |

|

| Transmission |

|

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 98.0 in (2,489 mm) (MY1963) [6] |

| Length | 179.3 in (4,554 mm) |

| Width | 69.6 in (1,768 mm) |

| Height | 49.6 in (1,260 mm) Coupe, convertible with hardtop, 49.8 in (1,265 mm) Convertible with soft top |

| Curb weight | 3,362 lb (1,525 kg) |

| Chronology | |

| Predecessor | Chevrolet Corvette (C1) |

| Successor | Chevrolet Corvette (C3) |

History

Origin and development

The 1963 Sting Ray production car's lineage can be traced to two separate GM projects: the Q-Corvette, and Bill Mitchell's racing Sting Ray. The Q-Corvette exercise of 1957 envisioned a smaller, more advanced Corvette as a coupe-only model, boasting a rear transaxle, independent rear suspension, and four-wheel disc brakes, with the rear brakes mounted inboard. Exterior styling was purposeful, with peaked fenders, a long nose, and a short, bobbed tail.

Meanwhile, Zora Arkus-Duntov and other GM engineers had become fascinated with mid and rear-engine designs. Duntov explored the mid/rear-engine layout with the lightweight, open-wheel, single-seat CERV I concept of 1959. A rear-engined Corvette was briefly considered during 1958–60, progressing as far as a full-scale mock-up designed around the Corvair's entire rear-mounted power package, including its air-cooled flat-six, as an alternative to the Corvette's usual water-cooled V8. By the fall of 1959, elements of the Q-Corvette and the Sting Ray Special racer would be incorporated into experimental project XP-720, which was the design program that led directly to the production 1963 Corvette Sting Ray. The XP-720 sought to deliver improved passenger accommodation, more luggage space, and superior ride and handling over previous Corvettes.

While Duntov was developing an innovative new chassis for the 1963 Corvette, designers were adapting and refining the basic look of the racing Sting Ray for the production model. A fully functional space buck (a wooden mock-up created to work out interior dimensions) was completed by early 1960, production coupe styling was locked up for the most part by April, and the interior, instrument panel included, was in place by November. Only in the fall of 1960 did the designers turn their creative attention to a new version of the traditional Corvette convertible and, still later, its detachable hardtop. For the first time in the Corvette's history, wind tunnel testing influenced the final shape, as did practical matters like interior space, windshield curvatures, and tooling limitations. Both body styles were extensively evaluated as production-ready 3/8-scale models at the Caltech wind tunnel.

The vehicle's inner structure received as much attention as the aerodynamics of its exterior. Fiberglass outer panels were retained, but the Sting Ray emerged with nearly twice as much steel support in its central structure as the 1958–62 Corvette. The resulting extra weight was balanced by a reduction in fiberglass thickness, so the finished product actually weighed a bit less than the old roadster. Passenger room was as good as before despite the tighter wheelbase, and the reinforcing steel girder made the cockpit both stronger and safer.[8]

Design and engineering

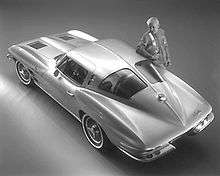

The first-ever production Corvette coupe sported a fastback body with a long hood and a raised windsplit that ran the length of the roof and continued down the back on a pillar that bisected the rear window into right and left halves. The split backlite is usually attributed to Mitchell, who claimed to have been inspired by the 57SC Bugatti "Atlantique" coupe. The feature actually predated both the C2 Corvette and Bob McLean's Q-Corvette, having been used by Harley Earl on both his Oldsmobile Golden Rocket show car and his own more traditional design studies for the C2 Corvette, some of which had progressed to full-scale models.[9] Earl's inspiration was said to have been an Alfa Romeo coupe with a body by Scaglione shown at the 1954 Turin Auto Show. A similar design would be used by the third-generation Buick Riviera that ran from 1971 to 1973.

Quad headlamps were retained but newly hidden – the first American car so equipped since the 1942 DeSoto. The lamps were mounted in rotating housings that blended with the sharp-edged front end when "closed". Hidden headlamps would be a feature of the Corvette until the C6 model debuted in 2005. Coupe doors were cut into the roof, which made entry/exit easier in such a low-slung closed car. Faux vents were located in the hood and on the coupe's rear pillars; functional ones had been intended but were cancelled due to cost considerations.

The Sting Ray's interior carried a re-interpretation of the twin-cowl Corvette dash motif used since 1958, but a more practical one incorporating a roomy glovebox, an improved heater, and the cowl-ventilation system. A full set of round gauges included a huge speedometer and tachometer. The control tower center console returned, somewhat slimmer but now containing the clock and a vertically situated radio. Luggage space was improved as well, although due to the lack of an external trunklid, cargo had to be loaded behind the seats. The spare tire was located at the rear in a drop-down fiberglass housing beneath the gas tank (which now held 20-US-gallon (76-litre; 17-imperial-gallon) instead of 16-US-gallon (61 l; 13 imp gal). The big, round deck emblem was newly hinged to double as a fuel-filler flap, replacing the previous left-flank door.

Though not as obvious as the car's radical styling, the new chassis was just as important to the Sting Ray's success. Maneuverability was improved thanks to the faster recirculating ball, or "Ball-Race", steering, and a shorter wheelbase. The latter might ordinarily imply a choppier ride, but the altered weight distribution partly compensated for it. Less weight on the front wheels also meant easier steering, and with some 80 additional pounds on the rear wheels, the Sting Ray offered improved traction. Stopping power improved, too. Four-wheel cast-iron 11-inch drum brakes remained standard but were now wider, for an increase in effective braking area. Sintered-metallic linings, segmented for cooling, were again optional. So were Al-Fin brake drums, which not only provided faster heat dissipation (and thus better fade resistance) but less unsprung weight.[10] Power assist was available with both brake packages. Evolutionary engineering changes included positive crankcase ventilation, a smaller flywheel, and an aluminum clutch housing. A more efficient alternator replaced the old-fashioned generator.

The independent rear suspension created by Duntov was derived from the CERV I concept, and included a frame-mounted differential with U-jointed half-shafts tied together by a transverse leaf spring.[11] Rubber-cushioned struts carried the differential, which reduced ride harshness while improving tire adhesion, especially on rougher roads. The transverse spring was bolted to the rear of the differential case. A control arm extended laterally and slightly forward from each side of the case to a hub carrier, with a trailing radius rod mounted behind it. The half-shafts functioned like upper control arms. The lower arms controlled vertical wheel motion, while the trailing rods took care of fore/aft wheel motion and transferred braking torque to the frame. Shock absorbers were conventional twin-tube units. Considerably lighter than the old solid axle, the new rear suspension array delivered a significant reduction in unsprung weight, which was important since the 1963 model would retain the previous generation's outboard rear brakes. The new model's front suspension would be much as before, with unequal-length upper and lower A-arms on coil springs concentric with the shocks, plus a standard anti-roll bar. Steering remained the conventional recirculating-ball steering design, but it was geared at a higher 19.6:1 overall ratio (previously 21.0:1). Bolted to the frame rail at one end and to the relay rod at the other was a new hydraulic steering damper (essentially a shock absorber), which helped soak up bumps before they reached the steering wheel. What's more, hydraulically assisted steering would be offered as optional equipment for the first time on a Corvette – except on cars with the two most powerful engines – and offer a faster 17.1:1 ratio, which reduced lock-to-lock turns from 3.4 to just 2.9.

Drivetrains were carried over from the previous generation, comprising four 327 cu in (5,360 cc) small block V8s, three transmissions, and six axle ratios. Carbureted engines came in 250 hp (186 kW), 300 hp (224 kW), and 340 hp (254 kW) versions. As before, the base and optional units employed hydraulic lifters, a mild camshaft, forged-steel crankshaft, 10.5:1 compression, single-point distributor, and dual exhausts. The 300-bhp engine produced its extra power via a larger four-barrel carburetor (Carter AFB instead of the 250's Carter WCFB), plus larger intake valves and exhaust manifold. Again topping the performance chart was a 360 hp (268 kW) fuel-injected V8, available for an extra $430.40. The car's standard transmission remained the familiar three-speed manual, though the preferred gearbox continued to be the Borg-Warner manual four-speed, changing over to the Muncie M20 during the 1963 model year, delivered with wide-ratio gears when teamed with the base and 300-bhp engines, and close-ratio gearing with the top two powerplants. Standard axle ratio for the three-speed manual or two-speed Powerglide automatic was 3.36:1. The four-speed gearbox came with a 3.70:1 final drive, but 3.08:1, 3.55:1, 4.11:1, and 4.56:1 gearsets were available. The last was quite rare in production, however.[8]

.jpg)

Corvette's designers and engineers – Ed Cole, Duntov, Mitchell, and others – knew that after 10 years in its basic form, albeit much improved, it was time to move on. By decade's end, the machinery would be put into motion to fashion a fitting successor to debut for the 1963 model year. After years of tinkering with the basic package, Mitchell and his crew would finally break the mold of Harley Earl's original design once and for all. He would dub the Corvette’s second generation "Sting Ray" after the earlier race car of the same name. The C2 was designed by Larry Shinoda (Pete Brock was also instrumental on the C2) under the direction of GM chief stylist Bill Mitchell. Inspiration was drawn from several sources: the contemporary Jaguar E-Type, one of which Mitchell owned and enjoyed driving frequently; the radical Sting Ray Racer Mitchell designed in 1959 as Chevrolet no longer participated in factory racing; and a Mako shark Mitchell caught while deep-sea fishing. Duntov disliked the split rear window (which also raised safety concerns due to reduced visibility)[12] and it was discontinued in 1964, as were the fake hood vents.

Model year changes

1963

The 1963 Corvette Sting Ray not only had a new design, but also newfound handling prowess. The Sting Ray was also a somewhat lighter Corvette, so acceleration improved despite unchanged horsepower. For the 1963 model year, 21,513 units would be built, which was up 50 percent from the record-setting 1962 version. Production was divided almost evenly between the convertible and the new coupe – 10,919 and 10,594, respectively – and more than half the convertibles were ordered with the optional lift-off hardtop. Nevertheless, the coupe wouldn't sell as well again throughout the Sting Ray years. The closed Corvette did not outsell the open one until 1969, by which time the coupe came with a T-top featuring removable roof panels.[13] Equipment installations for 1963 began reflecting the market's demand for more civility in sporting cars. The power brake option went into 15 percent of production, power steering into 12 percent. On the other hand, only 278 buyers specified the $421.80 air conditioning; leather upholstery – a mere $80.70 – was ordered on only 1,114 cars. The cast aluminum knock-off wheels, manufactured for Chevy by Kelsey-Hayes, cost $322.80 a set, but few buyers checked off that option. However, almost 18,000 Sting Rays left St. Louis with the four-speed manual gearbox – better than four out of every five.[14]

All 1963 cars had 327cid engines, which made 250 hp standard, with optional variants that made 300 hp, 340 hp and 360 hp. The most powerful engine was the Rochester fuel injected engine. Options available on the C2 included AM-FM radio (mid 1963), air conditioning, and leather upholstery. Also available for the first time ever on a Corvette was a special performance equipment package the RPO Z06, for $1,818.45. These Corvettes came to be known as the "Big Tanks" because the package initially had a 36.5-US-gallon (138 l; 30.4 imp gal) gas tank versus the standard 20-gallon for races such as Sebring and Daytona. At first, the package was only available on coupes because the oversized tank would not fit in the convertible.

In 1963 only 199 Z06 Corvettes were produced, usually reserved for racing, and of the 199 a total of six were specifically created for Le Mans racing by Chevrolet. One of the six 1963 Z06 Sting Ray's was built late in 1962 to race at Riverside on 13 October 1962.[15] They were destined to compete in a different sort of race for sports cars, a NASCAR sanctioned event on the famous Daytona Oval, the Daytona 250 – American Challenge Cup. This meant the cars needed to be prepared to a different set of rules, the same as those for the big Grand National stock cars. The chassis was modified extensively and an experimental 427 cu in (7,000 cc) engine installed.[16] The car was lightened in every way possible and weighed just over 2,800 lb (1,300 kg). Further prep was done by Mickey Thompson. Among other changes, Thompson replaced the fiberglass Z06 "Big Tank" with an even larger 50 US gal (189.3 l; 41.6 imp gal) metal tank.[17] Driven by Junior Johnson, plagued by rain in the race, substitute driver Billy Krause finished third behind Paul Goldsmith's Pontiac Tempest and A. J. Foyt in another Corvette.[16][18]

New for the 1963 model year was an optional electronic ignition, the breakerless magnetic pulse-triggered Delcotronic, first offered by Pontiac on some 1963 models.[19]

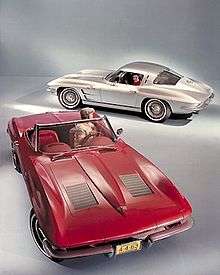

1964

For 1964 Chevrolet made only evolutionary changes to the Corvette. Besides the coupe's backbone window, the two simulated air intakes were eliminated from the hood, though their indentations remained. Also, the decorative air-exhaust vent on the coupe's rear pillar was made functional, but only on the left side. The car's rocker-panel trim lost some of its ribs and gained black paint between those ribs that remained; wheel covers were simplified; and the fuel filler/deck emblem gained concentric circles around its crossed-flags insignia. Inside, the original color-keyed steering wheel rim was now done in simulated walnut.

A few suspension refinements were made for 1964. The front coil springs were changed from constant-rate to progressive or variable-rate and were more tightly wound at the top, while leaf thickness of the rear transverse spring was also altered thus providing a more comfortable ride with no sacrifice in handling. Shock absorbers were reworked toward the same end. The 1964 Corvette arrived with a new standard shock containing within its fluid reservoir a small bag of Freon gas that absorbed heat. Chevy added more sound insulation and revised body and transmission mounts for the 1964 Corvette. It also fitted additional bushings to quiet the shift linkage and placed a new boot around the lever. The result was a more livable car for everyday transportation.

Drivetrain choices remained basically as before but the high-performance pair received several noteworthy improvements. The solid-lifter unit was driven with a high-lift, long-duration camshaft to produce 365 hp (272 kW) and breathed through a big four-barrel Holley carburetor instead of the base engine's Carter unit. The fuel injected engine also gained 15 horsepower (11 kilowatts), bringing its total to 375 hp (280 kW), but at a then-hefty $538.00. Although transmission options remained ostensibly the same for 1964, the two Borg-Warner T-10 four-speeds gave way to a similar pair of gearboxes built at GM's Muncie, Indiana, transmission facility. Originally a Chevy design, it had an aluminum case like the Borg-Warner box but came with stronger synchronizers and wider ratios for better durability and drivability. If enthusiast publications liked the first Sting Ray, they loved the 1964, though some writers noted the convertible's tendency to rattle and shake on rough roads. Sales of the 1964 Sting Ray reached 22,229 -— another new Corvette record, if up only a little from banner-year 1963. Coupe volume dropped to 8304 units, but convertible sales more than compensated, rising to 13,925.[14][13]

1965

For its third season, the 1965 Corvette Sting Ray further cleaned up style-wise and was muscled up with the addition of an all-new braking system and larger power plants. 1965 styling alterations were subtle, confined to a smoothed-out hood now devoid of scoop indentations, a trio of working vertical exhaust vents in the front fenders that replaced the previous nonfunctional horizontal "speedlines," restyled wheel covers and rocker-panel moldings, and minor interior trim revisions. The 1965 Corvette Sting Ray became ferocious with the mid-year debut of the "Big-Block" 396 cu in (6,490 cc) engine producing 425 hp (317 kW). Ultimately, this spelled the end for the Rochester fuel injection system, as the carbureted 396ci/425hp option cost $292.70 to the fuel injected 327ci/375hp's $538.00. Few buyers could justify $245 more for 50 hp (37 kW) less, even if the FI cars offered optional bigger brakes not available on carbureted models.[20]:77 After only 771 fuel injected cars were built in 1965, Chevrolet discontinued the option. It would be 18 years until it returned.

1965 also added another 350 hp small block engine (Option L79) which used hydraulic rather than solid lifters, a milder camshaft and a modestly redesigned smaller oil pan.[21] Otherwise, the 350 hp engine was cosmetically and mechanically identical to the 365 hp engine (Option L76) solid lifter engine. The smaller oil pan allowed this high output small block 350hp engine to be ordered with optional Power Steering for the first time amongst the optional stable of higher output small block engines. Power steering was previously only available with the lower 250 hp and 300 hp engines.

Four-wheel disc brakes were also introduced in 1965. The brakes had a four-piston design with two-piece calipers and cooling fins for the rotors. Pads were in frequent contact with the rotors, but the resulting drag was negligible and did not affect fuel economy. Further, the light touching kept the rotors clean and did not diminish pad life, which was, in fact, quite high: a projected 57,000 mi (92,000 km) for the front brakes and about twice that distance for the rear binders. Total swept area for the new system was 461 sq in (2,970 cm2), a notable advance on the 328 sq in (2,120 cm2) of the previous all-drum system. Per pending federal regulation, there was also a dual master cylinder with separate fluid reservoirs (only on models with power brakes for 1965)[22] for the front and rear lines. Road testers rightly applauded the all-disc brakes. Testers found that repeated stops from 100 mph (160 km/h) produced no deterioration in braking efficiency, and even the most sudden stops were rock-stable. The drum brakes remained available, however, as a $64.50 credit option, but only 316 of the 23,562 Corvettes built that year came with drums.[14][13] A side exhaust system appeared as an option as did a telescopic steering wheel. Also available were alloy spinner rims, at US$322 a set.[20]:77

1966

For the 1966 Corvette, the big-block V8 came in two forms: 390 hp (290 kW) on 10.25:1 compression, and 425 bhp via 11:1 compression, larger intake valves, a bigger Holley four-barrel carburetor on an aluminum manifold, mechanical lifters, and four- instead of two-hole main bearing caps. Though it had no more horsepower than the previous high-compression 396, the 427 cu in (7,000 cc), 430 hp (320 kW) V8 packed a lot more torque – 460 lb⋅ft (624 N⋅m) vs. 415 lb⋅ft (563 N⋅m). In the 1960s engine outputs were at times deliberately understated. This happened for two reasons; to placate nervous insurance companies, and to allow the cars to qualify for lower NHRA brackets based on horsepower and weight.[23] Estimates of 420 to 450 hp (313 to 336 kW) for the 427 have been suggested as being closer to the truth. Conversely, power ratings in the sixties were done in SAE Gross Horsepower, which is measured on an engine without accessories or air filter or restrictive stock exhaust manifold, invariably giving a significantly higher rating than the engine actually produces when installed in the automobile.[24] SAE Net Horsepower is measured with all accessories, air filters and factory exhaust system in place; this is the standard that all US automobile engines have been rated at since 1972. With big-block V8s being the order of the day, there was less demand for the 327, so small-block offerings were cut from five to two for 1966, and only the basic 300- and 350-bhp versions were retained. Both required premium fuel on compression ratios well over 10.0:1, and they didn't have the rocket-like thrust of the 427s, but their performance was impressive all the same. As before, both could be teamed with the Powerglide automatic, the standard three-speed manual, or either four-speed option.

The 1966 model's frontal appearance was mildly altered with an eggcrate grille insert to replace the previous horizontal bars, and the coupe lost its roof-mounted extractor vents, which had proven inefficient. Corvettes also received an emblem in the corner of the hood for 1966. Head rests were a new option, one of the rarest options was the Red/Red Automatic option with power windows and air conditioning from factory which records show production numbered only 7 convertibles and 33 coupes. This relative lack of change reflected plans to bring out an all-new Corvette for 1967. It certainly did not reflect a fall-off in the car's popularity, however. In fact, 1966 would prove another record-busting year, with volume rising to 27,720 units, up some 4,200 over 1965s sales.[14][25]

1967

The 1967 Corvette Sting Ray was the last Corvette of the second generation, and five years of refinements made it the best of the line. Although it was meant to be a redesign year, its intended successor the C3 was found to have some undesirable aerodynamic traits. Duntov demanded more time in the wind tunnel to devise fixes before it went into production.

Changes were again modest: Five smaller front fender vents replaced the three larger ones, and flat-finish rockers sans ribbing conferred a lower, less chunky appearance. New was a single backup light, mounted above the license plate. The previous models' wheel covers gave way to slotted six-inch Rally wheels with chrome beauty rings and lug nuts concealed behind chrome caps. Interior alterations were modest and included revised upholstery, and the handbrake moved from beneath the dash to between the seats. The convertible's optional hardtop was offered with a black vinyl cover, which was a fad among all cars at the time.

The 427 was available with a 1282 ft³/min (605 L/s) Rochester 3X2-barrel carburetors arrangement, which the factory called Tri-Power producing 435 bhp (441 PS; 324 kW) at 5800 rpm and 460 lb⋅ft (624 N⋅m) at 4000 rpm of torque.[26] The ultimate Corvette engine for 1967 was coded L88, even wilder than the L89, and was as close to a pure racing engine as Chevy had ever offered in regular production. Besides the lightweight heads and bigger ports, it came with an even hotter camshaft, stratospheric 12.5:1 compression, an aluminum radiator, small-diameter flywheel, and a single huge Holley four-barrel carburetor. Although the factory advertised L88 rating was 430 bhp at 4600 rpm, the true rating was said to be about 560 bhp at 6400 rpm. The very high compression ratio required 103-octane racing fuel, which was available only at select service stations. Clearly this was not an engine for the casual motorist. When the L88 was ordered, Chevy made several individual options mandatory, including Positraction, the transistorized ignition, heavy-duty suspension, and power brakes, as well as RPO C48, which deleted the normal radio and heater to cut down on weight and discourage the car's use on the street. As costly as it was powerful – at an additional $1,500 over the base $4,240.75 price – the L88 engine and required options were sold to a mere 20 buyers that year. With potential buyers anticipating the car's overdue redesign, sales for the Sting Ray's final year totaled 22,940, down over 5,000 units from 1966 results. Meanwhile, Chevrolet readied its third-generation Corvette for the 1968 model year.[14][27]

Engines

| Engine | Year | Power |

|---|---|---|

| 327 in³ Small-Block V8 | 1963–1965 | 250 hp (186 kW) |

| 1963–1967 | 300 hp (224 kW) | |

| 1963 | 340 hp (254 kW) | |

| 1965–1967 | 350 hp (254 kW) | |

| 1964–1965 | 365 hp (272 kW) | |

| 327 in³ Small-Block FI V8 | 1963 | 360 hp (268 kW) |

| 1964–1965 | 375 hp (280 kW) | |

| 396 in³ Big-Block V8 | 1965 | 425 hp (317 kW) |

| 427 in³ Big-Block V8 | 1966–1967 | 390 hp (291 kW) |

| 1966 | 425 hp (317 kW) | |

| 427 in³ Big-Block Tri-Power V8 | 1967 | 400 hp (298 kW) |

| 1967 | 435 hp (324 kW) |

Reviews

The Sting Ray was lauded in the automotive press almost unanimously for its handling, road adhesion, and sheer power.

Car Life magazine bestowed its annual Award for Engineering Excellence on the 1963 Sting Ray. Chevy's small-block V8 – the most consistent component of past Corvette performance – was rated by the buff books to be even better in the Sting Ray. The 1963 was noted to have an edge over past models in both traction and handling because the new independent rear suspension reduced wheel spin compared to the live-axle cars.

Motor Trend tested a four-speed fuel injected version with 3.70:1 axle. They reported a 0–60 mph in 5.8 seconds and a 14.5-second standing quarter-mile at 102 mph. The magazine also recorded better than 18 miles per gallon at legal highway speeds and 14.1 mpg overall.

Motor Trend timed a 1964 fuel-injected four-speed coupe with the 4.11:1 rear axle, aluminum knock-off wheels (perfected at last and available from the factory), the sintered-metallic brakes, and Positraction through the quarter-mile in 14.2 seconds at 100 mph and the 0 to 60 mph in 5.6 seconds.

Road & Track tested the 300-bhp Powerglide automatic setup in a '64 coupe and recorded a 0–60 mph time of 8.0 seconds, a quarter-mile in 15.2 seconds at 85 mph, and average fuel consumption of 14.8 mpg.

In 2004, Sports Car International named the Sting Ray number five on the list of Top Sports Cars of the 1960s.

Production notes

| Year | Production | Base Price | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | 21,513 | $4,037 | New coupe bodystyle introduced (only year for split rear window), coupe more expensive than convertible. |

| 1964 | 22,229 | $4,037 | Rear window of coupe changed to single pane; hood louvers deleted. |

| 1965 | 23,562 | $4,106 | 396 in3 Big-Block V8 added; side-discharge exhaust introduced. Last year of fuel injection until 1982. |

| 1966 | 27,720 | $4,084 | 427 in3 Big-Block V8 with unique bulging hood; 327 in3 300-horsepower small block V8 standard. |

| 1967 | 22,940 | $4,240 | Five-louver fenders are unique; Big-Block hood bulge redesigned as a scoop; parking brake changed from pull-out under dash handle to lever mounted in center console; Solid lifter L88 427/430 would become most sought-after Corvette ever; only 20 were produced. |

| Total | 117,964 |

Gallery

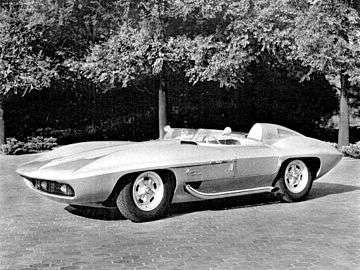

1959 Corvette Sting Ray Concept

1959 Corvette Sting Ray Concept 1963 Corvette Sting Ray Coupe

1963 Corvette Sting Ray Coupe 1965 Corvette Sting Ray Coupe

1965 Corvette Sting Ray Coupe 1967 Corvette Sting Ray Coupe

1967 Corvette Sting Ray Coupe

Z06

Duntov first conceived of the Z06 in 1962. Despite GM's ongoing support of the AMA ban on factory racing involvement, Duntov knew that individual customers would continue to race Corvettes, so during the planning of the Sting Ray project he suggested that it would be a good idea to continue with parts development in order to benefit racers, and as a way of surreptitiously circumventing the racing ban. When GM management eventually withdrew their support of the ban, Duntov and his colleagues created "RPO Z06" as a special performance equipment package for the Corvette. The Regular Production Option (RPO) was a GM internal ordering code designation. The package was specifically designed for competition-minded buyers, so they could order a race-ready Corvette straight from the factory with just one check of an option box. Previously, the optional racing parts were literally hidden in the order form so that only the most knowledgeable and perceptive customers could find them. The Z06 package was first offered on the 1963 Corvette, and included:[28]

- Front anti-roll bar with a 20% larger diameter

- Vacuum brake booster

- Dual master cylinder

- Sintered-metallic brake linings

- Power-assisted Al-Fin drums cooled by front air scoops and vented backing plates

- Larger diameter shocks and springs — nearly twice as stiff as those on the standard Corvette

These Corvettes came to be known as "Big Tanks" because the package initially replaced the 20 US gal (76 l; 17 imp gal) gas tank with a 36.5 US gal (138 l; 30 imp gal) tank for races such as Sebring and Daytona. At first the package was available only on coupes, as the oversized tank would not fit in the convertible, although the rest of the Z06 option package was later made available on convertibles as well.

Thus, the 1963 Corvette was technically the first Corvette that could be designated as "Z06." The only engine option on the Z06 was the L84 327 cu in (5.4 L) engine using Rochester fuel injection. With factory exhaust manifolds, required to run the cars in the SCCA production classes, Chevrolet rated the engine at 360 hp (268 kW). The Z06 option cost an additional $1,818.45 over the base coupe price of $4,252. Chevrolet later lowered the package price and eliminated the larger gas tank from the Z06 package, though it remained available as an add-on option for any coupe. All told, Chevrolet produced 199 of these "original" Z06s.[29]

Grand Sport

In 1962 Duntov initiated a program to produce a lightweight version based on a prototype that mirrored the new 1963 Corvette.[30] Concerned about Ford and the Shelby Cobra, Duntov's program included plans to build 125 examples of the Corvette Grand Sport to allow the model to be homologated for international Grand Touring races. After the GM executives learned of the secret project, the program was stopped, and only five cars were built. All five cars have survived and are in private collections. They are among the most coveted and valuable Corvettes ever built, not because of what they accomplished, but because of what might have been.[31]

The cars were driven by famed contemporary race drivers such as Roger Penske, A. J. Foyt, Jim Hall, and Dick Guldstrand among others. Dick Thompson was the first driver to win a race in the Grand Sport. He won a 1963 Sports Car Club of America race at Watkins Glen on August 24, 1963, driving Grand Sport 004.[32]

Chassis #001 is owned by former banker and car collector Harry Yeaggy of Cincinnati, Ohio. It was purchased for $4.2 million in 2002.[33]

Chassis 002 is a part of the permanent collection at the Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The car is in running condition, and is the only Grand Sport body which is original and unrestored. Also on display are a replica body and a spare 377 cubic inch engine, which were commissioned by the car's previous owner, Jim Jaeger, for participation in vintage racing without damaging the original components.[34]

Chassis #003 is owned by car collector Larry Bowman. It was bought in 2004 for an undisclosed sum.[35]

Chassis #004 is part of the Miles Collier Collection on display at The Revs Institute in Naples, Florida. This chassis was used in the Rolex Monterrey Motorsport Reunion in 2013.[36]

Chassis #005 is in the private collection of Bill Tower of Plant City, Florida. He was a former Corvette development engineer and also owns several historically significant Corvettes in his collection.[37]

The Corvette Grand Sports were raced with several different engines, but the most serious factory engine actually used was a 377 cubic inch displacement, all-aluminum, small block with four Weber side-draft carburetors and a cross-ram intake, rated 550 hp (410 kW) at 6400 rpm. Body panels were made of thinner fiberglass to reduce weight and the inner body structure 'birdcage' was aluminum rather than steel. The ladder-type frame utilized large seamless steel tubular side members connected front and rear with crossmembers of about the same diameter tubes. Another crossmember was just aft of the transmission and a fourth one at the rear kick-up anchored the integral roll cage. The frame was slightly stiffer than the 1963 Corvette production frame and was 94 lb (43 kg) lighter. A number of other lightweight components were utilized to reduce overall weight to about 800 pounds less than the production coupe.[30] Initially the Grand Sport project was known simply as "The Lightweight".[38]

Corvette Grand Sport #001

Corvette Grand Sport #001 Corvette Grand Sport #002

Corvette Grand Sport #002 Corvette Grand Sport #003

Corvette Grand Sport #003 Corvette Grand Sport #004

Corvette Grand Sport #004 Corvette Grand Sport #005

Corvette Grand Sport #005

Concept car

The 1963 Corvette Rondine (Ron-di-nay, Italian for Swallow) is a concept car based on a 1963 C2 chassis that was built for the 1963 Paris Auto Show. It was designed by Tom Tjaarda of Pininfarina.[39][40] It was sold at Barrett-Jackson 2008 for 1.6 million dollars.[41]

See also

- Corvette Stingray (concept car)

- Mako Shark (concept car)

- Chevrolet Engineering Research Vehicle

- Zora Arkus-Duntov

- Bill Thomas Cheetah, a 1963 private-venture Shelby Cobra rival, whose drivetrain was generally sourced from the C2 Corvette

References

Notes

- "Enter To Win a 1963 Corvette Sting Ray "Fuelie" and a 2017 Lingenfelter Signature Edition Corvette!". www.lingenfelter.com. 3 April 2017.

- "1967 Corvette Condensed Historical Facts". www.proteamcorvette.com. 1 May 2007.

- Teeters, K. Scott (30 March 2012). "A Look Back At Corvettes Designed by Larry Shinoda". www.corvettereport.com.

- "Duntov Motor Company - Performance Corvette Parts". Duntovmotors.com. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- "Superformance Corvette Grand Sport". www.superformance.com. 12 August 2019.

- "Chevrolet — 1963 Corvette Specifications" (PDF). GM Heritage Center. Cite magazine requires

|magazine=(help) - Corvette 50th Anniversary by the Editors of Consumer Guide

- The Editors of Consumer Guide

- Brock 2013, p. 42–45, 101–105.

- Bond, John R. (October 1962). "The 1963 Corvette - A technical analysis". Road & Track.

- Rudeen, Kenneth (1 October 1962). "A Detroit challenge to the best from Europe". Sports Illustrated. pp. 58–60.

- Flory 2004, p. 203.

- Antonick 1999.

- Corvette 50th Anniversary

- "Riverside 3 Hours". Racing Sports Cars. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Gillogy, Brandan (10 September 2015). "Mickey Thompson Z06 Mystery Motor Stingray". Hot Rod Network. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Kimble, David (December 2015). "427 Mystery Motor Corvettes". Hot Rod. TEN: The Enthusiast Network Magazines, LLC.

- "Daytona 250 Miles - American Challenge Cup". www.racingsportscars.com.

- Super Street Cars, 9/81, p.35.

- Hot Rod Magazine's Street Machines and Bracket Racing #5 (Peterson Publishing, 1981), p.77.

- "1965 Corvette Specs". www.corvettemuseum.org.

- "65/66 Single/Dual Master Cylinder? - CorvetteForum - Chevrolet Corvette Forum Discussion". www.corvetteforum.com.

- Potrebić, Nikola (26 October 2019). "The True HP of the 10 Most Powerful Classic Era Muscle Cars". autowise.com.

- Koscs, Jim (13 August 2013). "Muscle Car Horsepower – How Exaggerated Was It?". www.hagerty.com.

- 1966 Corvette Brochure

- "1967 Chevrolet Corvette 427 L71, 1968 MY 19400". www.carfolio.com.

- 1967 Corvette Brochure

- Staff, GM (2000). 2001 Specialist's Data Book Corvette. Michigan: Gail & Rice Productions, Inc. p. 48.

- Lachenauer, Scotty (4 September 2019). "The Big-Tank 1963 Chevrolet Corvette Z06 Is One of the Rarest American Cars Ever". www.automobilemag.com.

- Friedman and Paddock 1989, p. 16.

- Yates, Brock (April 1967). "Grand Sport!". Car and Driver. Vol. 12 no. 10. New York, New York: Ziff-Davis Publishing Company. pp. 48–52.

- Friedman and Paddock 1989, p. 36.

- "The Day the Corvette Grand Sports Stomped the Cobras". Super Chevy.

- Simeone, Frederick. "1963 Chevrolet Corvette Grand Sport". Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- "Untold Stories of the 1963 Chevrolet Corvette Grand Sport #003". Super Chevy.

- "1963 Chevrolet Corvette Grand Sport". Revs Institute. Retrieved 2019-08-02.

- "Bill Tower's Career as a Corvette Development Engineer". Super Chevy.

- "The Lightweight". Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Melissen, Wouter (21 January 2008). "Chevrolet Corvette Rondine Pininfarina Coupe". www.ultimatecarpage.com. Retrieved 2010-10-05.

- McKeegan, Noel (29 October 2007). "One-off Pininfarina-Bodied 1963 Corvette 'Rondine' Concept up for auction". www.gizmag.com.

- "Lot #1304 1963 CHEVROLET CORVETTE COUPE "RONDINE" CONCEPT CAR". www.barrett-jackson.com.

Bibliography

- Brock, Peter Corvette Sting Ray — Genesis of an American Icon. Henderson, NV: Brock Racing Enterprises LLC, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9895372-1-6.

- Flory, J. "Kelly", Jr. American Cars 1960–1972. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Coy, 2004. ISBN 978-0786412730.

- Antonick, Mike. "Corvette Black Book 1953–2000". Powell, Ohio: Michael Bruce Associates, Inc., 1999. ISBN 0933534469.

- Friedman, Dave and Paddock, Lowell C. Corvette Grand Sport: Photographic Race Log of the Magnificent Chevrolet Corvette Factory Specials 1962–1967. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Co., 1989. ISBN 0-87938-382-8.

- Holmes, Mark (2007). Ultimate Convertibles: Roofless Beauty. London: Kandour. pp. 54–59. ISBN 978-1-905741-62-5..

- Mueller, Mike. Corvette Milestones. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Co., 1996. ISBN 0-7603-0095-X.

- Nichols, Richard. Corvette: 1953 to the Present. London: Bison Books, 1985. ISBN 0-86124-218-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chevrolet Corvette C2. |

- 1963 Corvette - C2 Corvette history and technical development

- 1963 Corvette Grand Sport - Detailed history and images of the Grand Sport Corvette

- 1965 Corvette convertible - 1965 Corvette convertible