Mulsanne Straight

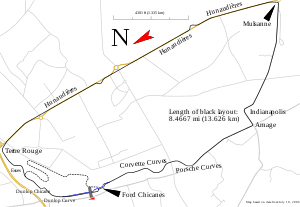

The Mulsanne Straight (Ligne Droite des Hunaudières in French) is the name used in English for a formerly 6 km (3.7 mi) long straight of the Circuit de la Sarthe around which the 24 Hours of Le Mans auto race takes place. Since 1990, the straight is interrupted by two chicanes, with the last section (that includes a slight right turn known as the "Kink") leading to a sharp corner near the village of Mulsanne.

French name

When races are not taking place, the Mulsanne Straight is part of the national road system of France. It is called the Ligne Droite des Hunaudières, a part of the route départementale RD 338 (formerly Route Nationale RN 138) in the Sarthe department. The Hunaudières leads to the village of Mulsanne, its English namesake (though the French Route de Mulsanne is the name for the road between Mulsanne and Arnage, with the Indianapolis corner in between).[1]

History

After exiting the Tertre Rouge corner, cars would spend almost half of the lap at full throttle, before braking for Mulsanne Corner. The Porsche 917 longtail with its 5.0-litre flat-12 engine, used from 1969 to 1971, had reached 362 km/h (225 mph).[2] After this, engine size was limited and top speeds dropped until powerful turbocharged engines, pioneered by French manufacturer Renault, were allowed, as in the 1978 Porsche 935 which was clocked at 367 km/h (228 mph).[3]

Speeds on the straight by Group C prototypes reached over 400 km/h (250 mph) during the late 1980s. At the beginning of the 1988 24 Hours of Le Mans race, Paris garage owner Roger Dorchy drove for Welter Racing in a car dubbed the WM P88. The P88 belonged to a program known as "Project 400" and was powered by a 2.8-litre turbocharged Peugeot PRV V6 engine, which sacrificed reliability for power. As a result, the car was out after just 53 laps (or approximately 4 hours) with turbo, cooling and electrical failures. It was measured by radar travelling at an all-time race record speed of 407 km/h (253 mph).[4]

There were fatal high-speed accidents on the Mulsanne Straight in the 1980s. Jean-Louis Lafosse was killed in 1981, and Jo Gartner in 1986; in 1984 a French track marshal was killed in an accident at the Kink involving the two Aston Martin Nimrod NRA/C2s of British driver John Sheldon and his American teammate Drake Olson.[5] One driver had an extremely lucky escape in 1986: a tyre on British driver Win Percy's 7.0 litre V12-powered Jaguar XJR-6 exploded at 386 km/h (240 mph), tearing off the rear bodywork and flipping the car into the air "up above the trees".[6] The wreckage finally came to a halt 600 metres down the road. Although the vehicle was almost obliterated, Percy somehow walked away from the crash with nothing more than a badly battered helmet.

Addition of chicanes

As the combination of high speed and high downforce caused tyre and engine failures, two chicanes were added to the straight before the 1990 race to limit the achievable maximum speed.[7] The chicanes were added also because the FIA decreed it would no longer sanction a circuit with a straight longer than 2 km (1.2 mi),[8] which is roughly the length of the Döttinger Höhe straight on the Nürburgring Nordschleife. The chicanes have successfully limited top speeds on the Mulsanne, with most of the leading cars topping out at approximately 330 km/h (205 mph) during qualifying and 320 km/h (199 mph) during the race.

The Nissan R90CK is notable for achieving the highest straight line speed on the Mulsanne Straight at the Le Mans circuit following the installation of these chicanes. Mark Blundell reached a speed of 366 km/h (226.9 mph) during qualifying when the twin-turbo system's wastegate was stuck shut, leading the engine to produce well over its regular output of 1,000 bhp. The exact power increase remains unknown.[9]

Spectator access

In the past, spectators could obtain magnificent views of cars racing along the straight during the Le Mans, including while dining at various restaurants—such as Restaurant de 24 Heures and Les Virages de L'Arche—located very close to the road. However, in 1990, the viewing experience obtained at both restaurants was diminished with the introduction of the chicanes.[10]

Today, due to safety concerns, spectators are kept well away from the edge of the straight by marshals and police, and while dining guests can still hear the cars pass, their view is obscured by green covers attached to the safety fencing.[11][12]

As a namesake

Three Bentley cars are named after the straight and nearby villages: the Hunaudières concept car, the Mulsanne, and the Arnage.

Notes

- Hergault 2011.

- Fuller 2010.

- Leffingwell, Randy (2005). Porsche 911: Perfection by Design. Motorbooks. p. 155.

- http://www.mulsannescorner.com/maxspeed.html

- "1984 - Le Mans — John Sheldon's massive crash". Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2002-01-02. Retrieved 2016-07-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Speedhunters staff 2008.

- RC staff 2015.

- Pruett, Marshall (January 19, 2017). "How a Broken Turbo Gave this Nissan 1000+ Horsepower and Nearly Set a Speed Record". Road & Track. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- MSM staff 1990.

- Bonardel 2015.

- RT staff 2015.

References

- Hergault, Julien (2011-08-04). "The Highway of Records". lemans.org. Archived from the original on 2019-08-14. Retrieved 2019-08-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bonardel, Cécile (2015-04-09). "24 Hours of Le Mans - The legendary spots on the circuit: The Mulsanne Straight". lemans.org. Archived from the original on 2019-07-03. Retrieved 2019-08-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fuller, Michael J. (2010), "Mulsanne's Corner: Maximum Speeds at Le Mans, 1961-1989", Mulsanne's Corner, technical analysis of contemporary sports prototype racing cars, retrieved 25 July 2015

- MSM staff (June 1990), "Le Mans Spectator Guide", Motor Sport Magazine Archive, retrieved 25 July 2015

- RC staff (2015), "Le Mans", RacingCircuits.info, retrieved 25 July 2015

- RT staff (2015), "Eating & drinking at Le Mans", Race Tours, archived from the original on 6 September 2012, retrieved 25 July 2015

- Speedhunters staff (13 June 2008), "Temple Of Speed>> The Mulsanne Straight", Speedhunters, retrieved 25 July 2015CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)