1925 24 Hours of Le Mans

The 1925 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 3rd Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 20 and 21 June 1925. It was the last of the three races spanning 1923 to 1925 to determine the winner of the Rudge-Whitworth Triennial Cup, as well the second race of the inaugural Biennial Cup.

| 1925 24 Hours of Le Mans | |

| Previous: 1924 | Next: 1926 |

| Index: Races | Winners | |

Regulations

The Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) was pleased with how the 1924 regulations had worked. They adjusted the hood-test so that all cars could do it at the same time. The start was the logical point and to stop drivers from jumping the gun they would be lined up on the opposite side of the track. When the flag fell, they would run across, put the hood up and then start the car and get away as quick as possible. This became the origin of the famous “Le Mans start” that was an institution of the race until 1969, when safety concerns led to its end.[1]

The ACO offered a FF500 prize for the quickest to put up their hood,[2] and the French agent for Truffault-Hartford suspension parts offered a FF1000 prize to the car leading after the first lap. The hoods now had to stay up for at least the first twenty laps (about two hours), and they had to be examined by officials for robustness before being pulled down. In addition to the 20-lap rule between fluid replenishment, no liquids could now be added after 3pm, in the final hour of the race.[1]

Another important change was that every car had to cross the finish line and take the chequered flag to be classified. Using the cars’ average race speeds, the officials would calculate each car's estimated position on the track at the 24-hour mark. The sliding scale of target distances were again adjusted, though not as severely as 1924. The distances included the following:[1]

| Engine size |

1924 Minimum laps |

1925 Minimum laps |

Required Average speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3000cc | 115 | 118 | 84.9 km/h (52.8 mph) |

| 2000cc | 102 | 108 | 77.7 km/h (48.3 mph) |

| 1500cc | 93 | 99 | 71.2 km/h (44.2 mph) |

| 1100cc | 85 | 91 | 65.5 km/h (40.7 mph) |

This year there were a number of cash prizes awarded by the ACO and assorted sponsors for events ranging from leading at certain times to quietest and most comfortable cars.[1] Finally, this race was the culmination of the inaugural Triennial and Biennial Cups. Only seven manufacturers' entries remained who had completed both the 1923 and 1924 races to be in contention for the Triennial Cup. There were eight entrants for the Biennial Cup. Both would be decided solely by the results in this race, not from the combined aggregate.[3]

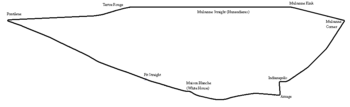

The Track

With the further success of the race, the ACO looked at getting more permanent facilities. They tried to purchase the properties around the pit area at Les Raineries however the prices demanded by the landowners were too high.[4] Frustrated, the ACO instead resolved to relocate with more amenable neighbours by the hippodrome along Les Hunaudières, the main route from Le Mans to Tours.[5] A new temporary pits, lighting and grandstands were set up on the Mulsanne Straight. The national roads board assisted by widening and sealing the track around the new pits area to assist with the new start procedure.[1]

Entries

The international attention that had come with Bentley's win the previous year drew a much bigger list of entries. Of the 68 submitted, 55 arrived for scrutineering. But this included 15 cars from outside France. Sunbeam, AC and Austin joined Bentley from Great Britain, and there were teams from Italy (Diatto and OM) and the USA (Chrysler). There were also six different tyre companies represented at the race.

| Category | Entries | Classes |

|---|---|---|

| Large-sized engines | 19 / 17 | over 2-litre |

| Medium-sized engines | 23 / 19 | 1.1 to 2-litre |

| Small-sized engines | 13 / 13 | up to 1.1-litre |

| Total entrants | 55 / 49 | |

- Note: The first number is the number of arrivals, the second the number who started.

After their distance victory the previous year, Bentley returned with a full works car to support John Duff’s privateer entry and carrying the “favourites” tag.[6] Duff had the same car as last year. The works car had an uprated 3.3-litre engine and was driven by Bentley salesman Bertie Kensington-Moir and Dudley Benjafield, a Harley St doctor and Bentley racer at Brooklands.[2]

Chenard-Walcker were well-placed in both Rudge-Whitworth Cups and arrived with four cars split over two engine-sizes to hedge their bets. The plan was to chase the Cups with the smaller cars and go for the distance victory with the bigger ones. Once again, their lead drivers René Léonard and André Lagache were assigned their primary car – the latest version of the 22CV. This was lower and now had a straight-8, 3.95-litre engine. The second car was driven by 1924 team hero André Pisart, and Jacques ‘Elgy’ Ledure, formerly with Bignan.[7] The smaller cars were inspired by the streamlined Bugatti Type 32 ‘tank’. Designer Henri Toutée's advanced Z1 was a racing version of the upcoming Y8 tourer. It had a new 1.1-litre engine produced 50 bhp and had new steering and 4-wheel braking, making it very quick. They were assigned to Sénéchal/Loqueheux and Glaszmann/de Zúñiga.[8]

.jpg)

After coming very close to victory the previous year, La Lorraine-Dietrich arrived with three of their B3-6 cars. The cars had been lightened, and the troublesome steel “artillery” wheels were replaced by Rudge-Whitworth wire ones. All three cars were now on Englebert tyres.[9] Last year's driver pairings were shuffled a bit: Gérard de Courcelles and André Rossignol stayed together, but Brisson was with Stalter and Robert Bloch with the new Léon Saint-Paul.

Sunbeam were now ready for Le Mans and arrived with two cars. Founded in 1899, the company came to pre-war prominence with French designer Louis Coatalen. Making aero-engines for Bristol during the war, they had been forced to merge with Talbot-Darracq in 1920, becoming STD. Already with a strong racing pedigree, with Land Speed Records for Kenelm Lee Guinness and Malcolm Campbell, they became the only British carmaker to win a Grand Prix in the first half of the twentieth century when Sir Henry Segrave won the 1923 French Grand Prix. Coatalen developed the two cars for Le Mans from the current production 24/60 model. The 2.9-litre engine put out 90 bhp with a 4-speed gearbox. With 4-wheel braking, they also ran with Rapson tyres like the Bentleys. Segrave was perhaps the most well-known British racing driver, and was paired with George Duller, while the second car had works drivers Jean Chassagne and Autocar journalist[10] Sammy Davis.[11] Originally a British company, Talbot had been bought out by the British-owned, Paris-based Darracq company 1919, which then merged with Sunbeam the next year. Its production was relocated to Paris and it was two of the 1.5-litre Type C, first made in 1923, that were sent to Le Mans.[12]

Ariès brought a newmodel to Le Mans this year. The Type S GP2 was lowered, with a shorter wheelbase and an improved 3-litre engine. This year company-owner Baron Charles Petiet was able to procure the services of the great Louis Wagner who had raced Darracq, FIAT and Mercedes before the war, and recently with the Alfa Romeo works team. Ariès also bought a pair of its smaller CC2 1100cc cars to compete for the 1924-5 Biennial Cup.[13]

The biggest car in the field was a Sizaire-Berwick, in the Anglo-French company's only Le Mans appearance. Designed by Maurice Sizaire in Paris, the cars had originally been made in London. Financial struggles saw that factory bought by Herbert Austin who put his own engines in the cars. The model at Le Mans had been built in France, its 4.5-litre engine putting out 65 bhp. Although big, it was also heavy and its performance lagged behind the new racing tourers.[14]

This year cars came from Italy for the first time, with two Italian teams. Diatto was an old industrial firm and had built railway-stock in the 19th century, including carriages for the famous Orient Express. It branched into cars in 1905 and had a solid pre-war racing pedigree. The works team was now run by Alfieri and Ernesto Maserati and four cars came to Le Mans. The Tipo 35 had a 3-litre engine putting out 75 bhp and capable of 135 kp/h (85 mph), while the pair of Tipo 30s had 55 bhp 2-litre engine.[15] Officine Meccaniche (OM) was a Milanese company that likewise building was founded, in 1899, building railway wagons. Car production started in 1918. The 665 “Superba” had come out five years later. It had a 2-litre engine, 4-speed gearbox and 4-wheel brakes. The model S was a short-wheelbase, racing version with Pirelli tyres and an improved engine that put out 60 bhp capable of over 120 kp/h (75 mph); and it had performed well at the national level. Three cars came to Le Mans with Italian drivers including Grand Prix drivers “Nando” Minoia and Giulio Foresti.[16]

It was also the first race for an American team. The first Chrysler-badged car had only been unveiled in 1924. The Chrysler 70 had a 3.3-litre straight-6 engine that produced 70 bhp capable of over 110 kp/h (70 mph). Dwarfed by the production of Ford and General Motors in the US, Chrysler set out to outset its rivals in Europe. The French agent was Gustave Baehr's Grand Garage Saint-Didier in Paris, and it was they who entered two cars into the race. In the end there was only time to prepare one – for former Lorraine-Dietrich driver Henri Stoffel and Lucien Desvaux, ex-Salmson.[17] The other new British team to enter was AC Cars. Originally making a 3-wheel delivery vehicle called an Auto Carrier, it was the post-war investment by famous British racer Selwyn Edge, that got the new AC Six into production. The entry was raced by John Joyce and Victor Bruce (engaged to famous female racer Mary Petre).[18]

Louis Reval had been in the automotive industry since the turn of the century. His company, Automobiles Reval, was only three years old. The latest iteration of his Type A had a 2.5-litre engine with a short-wheelbase Sports chassis and could reach 120 kp/h (75 mph).[19] Automobiles Gendron (also known as GM) was originally an auto-parts manufacturer, but started making cars in 1922. Two of the long-wheelbase GC-2 1.5-litre tourers were entered. Company founder Marcel Gendron himself drove one car, with accomplished aircraft test-pilot Lucien Bossoutrot.[20] Similarly, Henri Précloux was new to car-manufacturing, having opened E.H.P. in 1921, making small-engined cars and cyclecars that were competitive racers. The D4 model was new for 1925, and the DT was a higher-specification variant with a 1.5-litre CIME engine and 4-speed gearbox.[21]

Rolland-Pilain had released two new models this year: the B25 road-car and a “Super Sport” version of the B23, and it was three of the latter that were at Le Mans. It had a longer wheelbase, “boat-tail” rear end and a more powerful 2-litre engine.[22] The cars of Delalande/Chalamel and de Marguenet/Sire were entered in the Triennial Cup and with two cars, the team had a good chance in the Triennial field of seven. Bignan were struggling financially and only sent a pair of their 2-litre cars, to contest both of the ongoing Cups. The distinctive cars now sported on a single large headlight in the top of the radiator grill. Regular team drivers Jean Martin and Jean Matthys had one car, while Henri Springuel drove with Pierre Clause[23]

SARA again had three entries, and this year bought along a pair of its new Type BDE. Still with the 32 bhp 1100cc engine, they could now get up to 100 kp/h (60 mph).[24] Amilcar arrived with a works-entry CGS this year, to compete for the Triennial Cup. Team drivers were André Morel and Marius Mestivier.[25] However, this year they were not the smallest car in the field. Eric Gordon England, former Bristol test pilot, entered a 748cc Austin Seven. Built with his own patented ash and plywood bodywork design weighing only 9kg. He co-drove with Francis Samuelson.[26]

Practice

This year, the ACO was able to get the public roads closed to allow teams to do practice laps on the Friday – between 5am -8am and then 9pm-midnight.[1]

Earlier, in private practice, Léonard's Chenard-Walcker collided with a lorry coming away from the Pontlieue hairpin but was not badly damaged.[7] The Sunbeams developed issues and were sent to the Talbot sister-factory in Paris for repair, returning in time for the race.[11] Then tragedy struck on Friday evening. André Guilbert, a mechanic for Reval, was testing one of the cars when he hit a delivery van head-on when exiting the Pontlieue hairpin. He was taken to hospital with critical leg injuries.[3][19][6] On Saturday morning Oméga-Six company owner Gabriel Daubech withdrew his three cars. Team driver Jacques Margueritte had trialled two of the cars and picked up significant engine issues.

Race

Start

It was a hot, sunny weekend for the race and over twice as many spectators as the previous year arrived for the event.[27][6] Once again it was Émile Coquille, co-organiser and representative of the sponsor Rudge-Whitworth who was honorary starter. Just as the cars were forming up on the grid, the AC team found their radiator mounting was cracked, and with insufficient time to do a repair had to withdraw.[18][6] John Duff won the FF500 prize for being the first to put his hood up on his Bentley and get away,[28][6] followed by the big Sizaire-Berwick and Kensington-Moir in the other Bentley.[6] But at the end of the first lap it was Segrave in the Sunbeam in the lead, chased by the Bentleys, Saint-Paul's Lorraine and the two large Chenard-Walckers.[29][30][6]

On only the fourth lap, Pisart bought his Chenard in leaking water and overheating from a ruptured water-hose. After 40 minutes of repairs, they struggled on for two more laps but there was no way they could get to twenty for the next water refill.[7][6] In a similar predicament was the little Austin Seven, which got a stone thrown through the radiator after only nine laps.[26][6] With the new track surface, the drag of the hoods being up and fast race-pace several teams had miscalculated their fuel consumption. Kensington-Moir had just passed Segrave for the lead when the Bentley ran dry on his 20th lap near Pontlieue.[29][6] Just after that Duff too ran out. But he got back to the pits and illegally secreted a bottle of petrol back to the car to get it back to the pits, but losing seven laps.[28]

René Léonard was the first to pit, on the 20th lap, and Lagache was cheered away by the, naturally, parochial French spectators.[6] He set about lowering his own lap record by 9 seconds.

Then at dusk a serious accident occurred, The Amilcar of Marius Mestivier was just about to be overtaken by André Pisart's Chenard-Walcker just after the new finish-line approaching the Mulsanne corner. It suddenly slewed sideways off the track and rolled. Mestivier was crushed and killed instantly – the first fatality at the endurance race. Pisart made it round to the pits and retired the next lap with a ruptured water-hose causing overheating.[27]

At 9pm the Segrave/Duller Sunbeam retired with a broken clutch, while the sister car had been delayed by a sticking throttle.[27]

Night

As night fell Davis, in avoiding a backmarker, dropped the other Sunbeam off the road into a ditch. Despite a bent rear axle, he got back to the pits where the team inspected the car and resolved to carry on.[11] Just after midnight the suspension on Léon Saint-Paul's Lorraine broke at speed, throwing the car into three spins before rolling. Badly injured, Saint-Paul was pulled from the wreck by Tulio Vesprini (currently running 5th) who sportingly stopped his Diatto to help and then stayed with the driver until an ambulance arrived.[9]

Sénéchal finally handed over his 1100 to Loqueheux at midnight after driving solid for 8 hours. Both cars already looked to have a strong grip on their respective Cups. Sénéchal was back in his car at 2am when he went off the road and over the ditch in the fog at Arnage. Fashioning a bridge from some fencing, while lit by nearby spectators, he managed to get the car back onto the road and carried on in less than an hour.[8] Like the little Chenard-Walckers, the 2-litre Bignans had also been running exceptionally well, running third and fourth at 10pm – with the Springuel/Clause car possibly getting up to second overall going into Sunday, until both were delayed and lost time.[31]

As dawn approached by the halfway point at 4am[6] the Lorraine of Rossignol/de Courcelles had done 65 laps, holding a 2-lap lead over their teammates Brisson/Stalter. The recovering Sunbeam was third a further lap back and the Leduc/Auclair Talbot in fourth. With a trouble-free run, the leaders had pocketed a bundle of the FF500 bonus prizes – including first to 50 and 100 laps, and leading at the 11th and 12th hours[27] Fourth was the Le Du/Auclair Talbot with the Sénéchal/Loqueheux Chenard 1100 in fifth [refitting as bigger cars pitted and ran into troubles.[32] In the next fuel stops, the Bentley's engine caught fire. Despite Clement dowsing it with his seat-cushion, the damage was too severe to carry on.[28]

Morning

The remaining 4-litre Chenard retired when it too overheated from a ruptured water-hose and facing 8 laps until it could be replenished.[7] The sister cars were brought in for precautionary checks and had their hoses replaced. The Sunbeam finally caught and passed Brisson for second place around 6am.[30] By breakfast time, the Lorraines were split by the Sunbeam with two of the Italian OM's running very well in fourth and fifth.

As with the previous year, the Rolland-Pilains were compromised by their low fuel economy and could never push to their full potential. Although their lead car (of de Marguenat/Sire) was running well, in the top-10, the other two were delayed.[22]

Finish and post-race

The Chrysler had been having a strong reliable run that had got it up to 7th on distance. Then with less than two hours to go, Stoffel ended up in a ditch avoiding a slower car. The delay was crucial because, despite driving hard to make up lost time, they finished just two laps short of their qualifying distance.[17]

Meanwhile, the leading cars continued without further incident to the finish. In the end Rossignol and de Courcelles finished laps ahead of the opposition and ten laps ahead of their target. Chassagne and Davis in their Sunbeam held on to second, just ahead of the other Lorraine, of Brisson/Stalter. The two OMs came home in fourth and fifth staging a formation finish. The Danieli brothers were just ahead of teammates Foresti / Vassaux in a strong display of reliability from the newcomer team.[16]

The streamlined Chenard-Walcker 1100s ran like clockwork. The Glaszmann/de Zúñiga car finished 10th overall winning the inaugural Biennial Cup, while Sénéchal/Loqueheux came in 13th overall to win the first, and only, Rudge-Whitworth Triennial Cup (Sénéchal drove for over 20 hours). The cars were also sitting first and second respectively at the halfway point of the next Biennial Cup.

Although only one of the three Rolland-Pilains finished, it was as runner-up in the Triennial Cup. The team was also awarded one of the special cash prizes this year: FF500 for being judged one of the three most comfortable cars, a prize shared with the Ravel.[22] Sadly Ravel's mechanic, André Guilbert, died in hospital on the Tuesday following from his injuries.[19]

Small consolation for the Chrysler team for missing entry to the Biennial Cup was getting the FF500 prize for having the quietest car.[17] The two 3-litre Diattos had also been having a strong race. So it was tough when the Lecot/Renaud car had to retire with less than two hours to go. Rubbietti and Vesprini had been pushing hard making up for the time spent by Vesprini tending the injured Saint-Paul. But they fell short by two laps. However, the grateful Lorraine-Dietrich team donated them FF1000, with a further FF1000 given by the Hartford company and Saint-Paul's teammate Édouard Brisson.[15]

This was Chenard-Walker's finest hour. At the time they were France's third-biggest car manufacturer, assisted by their endurance racing successes. The top pairing of Lagache/Léonard won the second Spa 24-hours three weeks later (and were third the year after). However, the team never returned to Le Mans, the works team was disbanded at the end of 1926 and the company faded into obscurity.[7]

A number of companies were now starting to suffer in the saturated car-market as more high-volume production-line cars filled the streets. Lucien Rolland and Émile Pilain were forced by their board to sell their shares and their factory moved from Tours to Paris.[22] In 1926, E.H.P. bought out Bignan and Majola was taken over by Georges Irat.[33] And after the Italian government defaulted on its repayments for vehicles to Diatto, it was forced to dissolve its racing team at the end of the year.[15]

Official results

Finishers

Results taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO[34] Although there were no official engine classes, the highest finishers in unofficial categories aligned with the Index targets are in Bold text.

| Pos | Class *** |

No. | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Tyre | Target distance* |

Laps | Laps over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.0 | 5 | et Cie |

Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6 Sport |

Lorraine-Dietrich 3.5L S6 | E | 119 [B] | 129 | +10 | |

| 2 | 3.0 | 16 | Sunbeam 3 Litre Super Sports | Sunbeam 3.0L S6 | Rapson | 117 | 125 | +8 | ||

| 3 | 5.0 | 4 | et Cie |

Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6 Sport |

Lorraine-Dietrich 3.5L S6 | E | 119 [T][B] |

124 | +5 | |

| 4 | 2.0 | 29 | OM Tipo 665S Superba | OM 1991cc S6 | P | 108 | 121 | +13 | ||

| 5 | 2.0 | 30 | OM Tipo 665S Superba | OM 1991cc S6 | P | 108 | 121 | +13 | ||

| 6 | 3.0 | 11 | Ariès |

Ariès Type S GP2 | Ariès 3.0L S4 | M | 118 | 119 | +1 | |

| N/C ** |

5.0 | 7 | (private entrant) |

Chrysler Six 70 | Chrysler 3.3L S6 | BF | 119 | 117 | - | |

| 7 | 2.0 | 23 | Rolland et Pilain SA |

Rolland-Pilain C23 Super Sport | Rolland-Pilain 1997cc S4 | M | 108 [T] | 117 | +9 | |

| 8 | 1.5 | 41 | Automobiles Corre |

Corre La Licorne V16 10CV Sport | SCAP 1493cc S4 | E | 99 | 111 | +12 | |

| N/C ** |

3.0 | 14 | Autocostruzioni Diatto |

Diatto Tipo 35 | Diatto 3.0L S4 | E | 117 | 111 | - | |

| 9 | 1.5 | 42 | Automobiles Corre |

Corre La Licorne V16 10CV Sport | SCAP 1493cc S4 | E | 99 | 109 | +10 | |

| 10 | 1.1 | 50 | Chenard-Walcker Z1 Spéciale | Chenard-Walcker 1095cc S4 | M | 91 [B] | 109 | +18 | ||

| 11 | 2.0 | 21 | Autocostruzioni Diatto |

Diatto Tipo 30 | Diatto 1998cc S4 | E | 108 | 109 | +1 | |

| 12 | 2.0 | 33 | Jacques Bignan |

Bignan 2 Litre Sport | Bignan 1979cc S4 | E | 107 [B] | 109 | +2 | |

| 13 | 1.1 | 49 | Chenard-Walcker Z1 Spéciale | Chenard-Walcker 1095cc S4 | M | 91 [T] | 105 | +14 | ||

| 14 | 1.5 | 39 | EHP Type DT Spéciale | CIME 1496cc S4 | E | 99 | 104 | +5 | ||

| N/C ** |

3.0 | 18 | Ravel Type A Sport [12CV] | Ravel 2.5L I4 | D | 114 | 104 | - | ||

| 15 | 1.5 | 35 | & Cie |

GM GC2 Sport | CIME 1496cc S4 | D | 99 | 101 | +2 | |

| N/C ** |

2.0 | 22 | Rolland et Pilain SA |

Rolland-Pilain C23 Super Sport | Rolland-Pilain 1997cc S4 | M | 108 [T] | 99 | - | |

| 16 | 1.1 | 44 | Refroidissements par Air |

SARA ATS [7CV] | SARA 1099cc S4 | E | 91 | 94 | +3 |

- Note *: [T]= car entered in the Triennial Cup; [B]= car also entered in the 1924-5 Biennial Cup.

- Note **: Not Classified because did not meet target distance.

- Note ***: There were no official class divisions for this race. These are unofficial categories (used in subsequent years) related to the Index targets.

Did Not Finish

| Pos | Class *** |

No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Tyre | Target distance* |

Laps | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNF | 3.0 | 13 | Autocostruzioni Diatto |

Diatto Tipo 35 | Diatto 3.0L S4 | E | 117 | 109 | ? (23 hr) | |

| DNF | 1.5 | 36 | Talbot-Darracq Type C | Talbot 1496cc S4 | E | 99 | 98 | Accident (afternoon) | ||

| DNF | 5.0 | 2 | Chenard-Walcker Type U 22CV Sport | Chenard-Walcker 3.9L S8 | M | 120 | 90 [B] | Engine (morning) | ||

| DNF | 2.0 | 28 | OM Tipo 665S Superba | OM 1991cc S6 | P | 108 | 81 | Wheel bearing (17 hr) | ||

| DSQ | 1.5 | 37 | Talbot-Darracq Type C | Talbot 1496cc S4 | E | 99 | 73 | Premature refill (18 hr) | ||

| DSQ | 2.0 | 24 | Rolland et Pilain SA |

Rolland-Pilain C23 Super Sport | Rolland-Pilain 1997cc S4 | M | 108 | 70 | Premature refuel (15 hr) | |

| DNF | 2.0 | 32 | Jacques Bignan |

Bignan 2 Litre Sport | Bignan 1979cc S4 | E | 107 [T] | 65 | ? (dawn) | |

| DNF | 5.0 | 9 | (private entrant) |

Bentley 3 Litre Sport | Bentley 3.3L S4 | Rapson | 118 [T] | 64 | Fire (13 hr) | |

| DSQ | 1.1 | 47 | Doriot-Flandrin-Parant SA |

DFP Type VA | CIME 1099cc S4 | E | 91 | 60 | Insufficient distance (18 hr) | |

| DSQ | 3.0 | 17 | et Cie |

Ford-Montier Spéciale | Ford 2.9L S4 | E | 117 | 54 | Insufficient distance (12 hr) | |

| DNF | 1.5 | 40 | Automobiles Corre |

Corre La Licorne V16 10CV Sport | SCAP 1493cc S4 | E | 99 | 51 | ? (evening) | |

| DNF | 3.0 | 12 | Ariès |

Ariès Type S GP2 | Ariès 3.0L S4 | M | 118 | 42 | Electrics (8 hr) | |

| DNF | 2.0 | 20 | Autocostruzioni Diatto |

Diatto Tipo 30 | Diatto 1998cc S4 | E | 108 | 41 | ? (9 hr) | |

| DNF | 1.5 | 38 | EHP Type DT Spéciale | CIME 1496cc S4 | E | 99 | 41 | ? (night) | ||

| DNF | 1.1 | 45 | Refroidissements par Air |

SARA BDE | SARA 1099cc S4 | E | 91 | 40 | ? (night) | |

| DNF | 1.5 | 34 | & Cie |

GM GC2 Sport | CIME 1496cc S4 | D | 99 | 36 | ? (9 hr) | |

| DNF | 1.1 | 53 | Ariès |

Ariès CC2 | Ariès 1086cc S4 | M | 90 [B] | 35 | ? (night) | |

| DNF | 5.0 | 6 | et Cie |

Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6 Sport | Lorraine-Dietrich 3.5L S6 | E | 119 | 33 | Accident (9 hr) | |

| DNF | 3.0 | 15 | Sunbeam 3 Litre Super Sports | Sunbeam 2.9L S6 | Rapson | 117 | 32 | Transmission (6 hr) | ||

| DNF | 1.1 | 46 | Doriot-Flandrin-Parant SA |

DFP Type VA | CIME 1099cc S4 | E | 91 | 31 | ? (night) | |

| DNF | 5.0 | 1 | Voitures Sizaire-Berwick |

Sizaire-Berwick 25/50CV | Sizaire-Berwick 4.5L S4 | E | 120 | 23 | Engine (evening) | |

| DNF | 5.0 | 10 | Bentley 3 Litre Sport | Bentley 3.3L S4 | Rapson | 118 | 19 | Out of fuel (evening) | ||

| DNF | 1.1 | 48 | Doriot-Flandrin-Parant SA |

DFP Type VA | CIME 1099cc S4 | E | 91 | 19 | Out of fuel (evening) | |

| DNF | 1.1 | 51 | l'Automobile Amilcar |

Amilcar CGS | Amilcar 1089cc S4 | E | 90 [T] | 17 | Fatal accident, Mestivier (evening) | |

| DNF | 1.1 | 43 | Refroidissements par Air |

SARA BDE | SARA 1099cc S4 | E | 91 [B] | 15 | ? (evening) | |

| DNF | 1.1 | 52 | Majola Type F | Majola 1088cc S4 | D | 90 | 14 | Engine (evening) | ||

| DNF | 1.1 | 54 | Ariès |

Ariès CC2 | Ariès 1086cc S4 | M | 90 [B] | 11 | ? (afternoon) | |

| DNF | 750 | 55 | (private entrant) |

Austin 7 | Austin 748cc S4 | D | 82 | 9 | Radiator (afternoon) | |

| DNF | 5.0 | 3 | Chenard-Walcker Type U 22CV Sport | Chenard-Walcker 3.9L S8 | M | 120 | 6 | Engine (2 hr) | ||

| Sources: [35][36][37][38][39] | ||||||||||

Did Not Start

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNS | 3.0 | 19 | Ravel Type A Sport [12CV] | Ravel 2.5L I4 | Practice accident | ||

| DNS | 2.0 | 31 | AC Six 16/40 | AC 1991cc S6 | Radiator | ||

| DNS | 2.0 | 25 | Oméga-Six Type A | Oméga 1996cc S6 | Withdrawn after scrutineering | ||

| DNS | 2.0 | 26 | Oméga-Six Type A | Oméga 1996cc S6 | Withdrawn after scrutineering | ||

| DNS | 2.0 | 27 | Oméga-Six Type A | Oméga 1996cc S6 | Withdrawn after scrutineering | ||

| DNA | 5.0 | 8 | (private entrant) |

Chrysler Six 70 | Chrysler 3.3L S6 | Withdrawn |

Coupe Triennale Rudge-Whitworth Final Positions

| Pos | No. | Team | Drivers | Chassis | 1923 Laps Over |

1924 Laps Over |

1925 Laps Over |

Team Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 49 | Chenard-Walcker Z1 Spéciale | +49 | +8 | +14 | +14 | ||

| 2 | 23 | Rolland et Pilain SA |

Rolland-Pilain C23 Super Sport | +19 | +5 | +9 | +9 | |

| 3 | 4 | et Cie |

Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6 Sport | +26 | +0 | +6 | +6 | |

| - | 32 | Jacques Bignan |

Bignan 2 Litre Sport | +50 | +0 | DNF | - | |

| - | 51 | l'Automobile Amilcar |

Amilcar CGS | +41 | +4 | DNF | - | |

| - | 9 | (private entrant) |

Bentley 3 Litre Sport | +33 | +5 | DNF | - | |

| - | 22 | Rolland et Pilain SA |

Rolland-Pilain C23 Super Sport | +12 | +2 | DNF | - |

1924-25 Coupe Biennale Rudge-Whitworth

Highest Finisher in Class

| Class | Winning Car | Winning Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| 5 to 8-litre | no finishers | |

| 3 to 5-litre | #5 Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6 Sport | Rossignol / de Courcelles * |

| 2 to 3-litre | #16 Sunbeam 3-Litre Super Sports | Chassagne / Davis |

| 1500 to 2000cc | #29 OM Tipo 665S Superba | Danieli / Danieli * |

| 1100 to 1500cc | Corre La Licorne V16 10CV Sport | Balart / Doutrebente * |

| 750 to 1100cc | #50 Chenard-Walcker Z1 Spéciale | Glaszmann / de Zúñiga * |

| under 750cc | no finishers | |

- Note *: setting a new class distance record.

There were no official class divisions for this race and these are the highest finishers in unofficial categories (used in subsequent years) related to the Index targets.

Statistics

Taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO

- Fastest Lap – A. Lagache, #2 Chenard-Walcker Type U 22CV Sport – 9:10secs; 112.99 km/h (70.21 mph)

- Longest Distance – 2,233.98 km (1,388.13 mi)

- Average Speed on Longest Distance – 93.08 km/h (57.84 mph)

- Citations

- Spurring 2011, p.126

- Spurring 2011, p.144

- Spurring 2011, p.125

- Laban 2001, p.46

- Clausager 1982, p.32-4

- Clarke 1998, p.20-2: Motor Jun23 1925

- Spurring 2011, p.132-3

- Spurring 2011, p.131

- Spurring 2011, p.128-9

- Laban 2001, p.44

- Spurring 2011, p.133-5

- Spurring 2011, p.154-5

- Spurring 2011, p.149

- Spurring 2011, p.163

- Spurring 2011, p.150-2

- Spurring 2011, p.138

- Spurring 2011, p.140-1

- Spurring 2011, p.166

- Spurring 2011, p.155-6

- Spurring 2011, p.158

- Spurring 2011, p.158-9

- Spurring 2011, p.142

- Spurring 2011, p.146

- Spurring 2011, p.160

- Spurring 2011, p.157

- Spurring 2011, p.164-5

- Spurring 2011, p.127

- Spurring 2011, p.145-6

- Laban 2001, p.47

- Spurring 2011, p.136-7

- "Classement 1925". www.24h-en-piste.com (in French). Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "Classement 1925". www.24h-en-piste.com (in French). Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- Spurring 2015, p.165

- Spurring 2015, p.2

- Spurring 2011, p.168

- "Le Mans 24 Hours 1925 - Racing Sports Cars". www.racingsportscars.com. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "Le Mans History". www.lemans-history.com. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "World Sports Racing Prototypes". www.wsrp.cz. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- "Formula 2". www.formula2.net. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

References

- Clarke, R.M. - editor (1998) Le Mans 'The Bentley & Alfa Years 1923-1939' Cobham, Surrey: Brooklands Books ISBN 1-85520-465-7

- Clausager, Anders (1982) Le Mans London: Arthur Barker Ltd ISBN 0-213-16846-4

- Laban, Brian (2001) Le Mans 24 Hours London: Virgin Books ISBN 1-85227-971-0

- Spurring, Quentin (2015) Le Mans 1923-29 Yeovil, Somerset: Haynes Publishing ISBN 978-1-91050-508-3

External links

- Racing Sports Cars – Le Mans 24 Hours 1925 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

- Le Mans History – entries and results. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

- World Sports Racing Prototypes – results, reserve entries & chassis numbers. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

- 24h en Piste – results, chassis numbers & hour-by-hour places (in French). Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

- Unique Cars & Parts – results & reserve entries. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

- Radio Le mans – Race article and review by Charles Dressing. Retrieved 5 Dec 2018

- Formula 2 – Le Mans results & reserve entries. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018

- Motorsport Memorial – motor-racing deaths by year. Retrieved 31 Aug 2018