1950 24 Hours of Le Mans

The 1950 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 18th Grand Prix of Endurance, and took place on 24 and 25 June 1950. It was won by the French father-and-son pairing of Louis and Jean-Louis Rosier driving a privately entered Talbot-Lago.

| 1950 24 Hours of Le Mans | |

| Previous: 1949 | Next: 1951 |

| Index: Races | Winners | |

Regulations

The revival of motor-racing post-war was now in full swing – the FIA had published its new rules for single-seater racing and inaugurated the new Formula 1 World Championship. Its Appendix C addressed two-seater sportscar racing, giving some definition for racing prototypes. The same categories (based on engine capacity) were kept, although the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) added an extra class at the top end – for over 5.0L up to 8.0L.

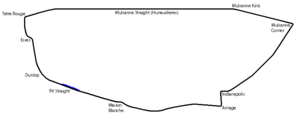

After last year’s issues with the hybrid ‘ternary’ fuel, the ACO now supplied 80-octane gasoline as standard, thereby removing the need. The track was widened except for the run from Mulsanne to Indianapolis, and the re-surfacing completed, thus promising to give faster times and be a quicker race.[1] Finally, the iconic Dunlop bridge was rebuilt – a footbridge over the circuit just after the first corner.[2]

Entries

A record 112 entries were received by the ACO, and they accepted 60 for the start – another record.[3][4] This year there were 24 entries in the S3000, S5000 and S8000 classes. The biggest car this year carrying the #1, was a MAP Diesel that was the first car to race at Le Mans with a mid-mounted engine (a supercharged 4.9L engine), with veteran racer and 1939 winner Pierre Veyron.

The first Americans to race at Le Mans in 21 years arrived - Briggs Cunningham bought across two 5.4L Cadillacs, one a standard Series 61 sedan and the other with an ugly aerodynamic bodyshell refined in the Grumman Aircraft wind tunnel.[5] They were soon nicknamed ‘’Petit Petaud (Small puppy)’’ and ‘’Le Monstre’’ respectively by the French, but Briggs saw the joke and had the names written on the bonnets beside the American flags.[6] Both were fitted with pit-to-car radios.

But this year, the big news was the first appearance of Jaguar – with three new 3.4L XK120s. Factory-prepared, they were released to select private entrants to test the waters.[3][7] Other British entries included an Allard with the big 5.4L Cadillac engine, co-driven by Sydney Allard himself; the Bentley saloon from last year returned, along with a second, even older (1934), car to represent the marque. This year Aston Martin came with three 2.6L DB2 works entries (now being run by John Wyer[8]).

After their spectacular success last year, Ferrari arrived with three 166 MM cars, as well as a new model: a pair of 195 S cars, with a bigger 2.4L V12, entered by last year’s winner Luigi Chinetti. This year Chinetti drove with Dreyfus, and was able to convince the great French driver Raymond Sommer (with whom he had won in 1932) to postpone his retirement to drive his other car.[9]

The French defended their home turf with a pair of fast privately-entered Talbot-Lago T26 (based on the current Grand Prix car) and the urbane SS coupe. Too heavy to be competitive in the new World Championship, their speed and durability made them ideal for Le Mans.[7] Charles Pozzi returned with two Delahaye 175 S in his new ‘’Ecurie Lutetia’’ team, the Delettrez brothers had their diesel special back, and two old Delage D6s returned (for the last time) including that of Henri Louveau who had staged such a spirited chase the year before. Also, with better preparation time, Amédée Gordini entered a big team of his new T15 cars, including two fitted with superchargers to take on the Ferraris. His regular Grand Prix drivers, Maurice Trintignant and Robert Manzon drove one and two new Argentinians Juan-Manuel Fangio and José Froilán González the other – all Le Mans debutants along with Jean Behra in a 1500 Gordini.

In the mid-size S2000 and S1500 classes, aside from the Ferraris and the two mid-size Gordinis, was an assortment of makes including Frazer-Nash, Jowett, Peugeot, Fiat and MG. If the French were under-represented in the big classes, they made up for it in the S1100 and S750 small-car categories, with 20 of the 25 entries, including works entries from Gordini, Monopole, Panhard, DB, Renault and Simca. The Aero-Minors from Czechoslovakia were back, and were joined by a Škoda in the S1100 class

Practice

In practice, Raymond Sommer showed that the new Ferraris were fastest, with a five-minute lap exactly – ahead of the Talbot-Lagos. Auguste Veuillet crashed and rolled his Delahaye, but after overnight repairs, it was ready for the race the next day, only for the car to refuse to start with a flat battery.

Race

Start

Lined up, as was Le Mans tradition, according to effective engine capacity, it was Tom Cole in the Allard who was the first to get going. Last to get away was Fangio’s Gordini with an engine misfire.[10] Sommer overtook a dozen cars to lead at the end of the first lap, ahead of Cole, Meyrat’s Talbot, Peter Whitehead in the new Jaguar and Trintignant in the supercharged Gordini.[11] On lap 2 Cunningham slid “Le Monstre” into the Mulsanne sandbank and had to spend 15 minutes digging it out[12] By the fifth lap, Rosier had his Talbot up to third and Chinetti had the other big Ferrari up to fifth.

It stayed pretty much like that for the first few hours with Sommer putting in some very fast laps, averaging just under 99 mph to extend his lead.[9][11] But then the pressure of that pace told and he lost a cylinder and had to pit with electrical problems from a dislodged alternator, dropping him to fifth. That let Rosier into the lead in the 3rd hour, and he then put in some blistering laps to break up the pursuing pack. As the sun set and in the cooler air he broke Sommer’s new lap record by almost ten secords with Le Mans’ first race lap averaging over 100 mph (160 km/h). At the end of four hours, it was Rosier, Chinetti, Sommer, Meyrat - Talbot, Ferrari, Ferrari, Talbot - then the Allard and the first Jaguar.

Night

Going into the night, Sommer/Serafini’s ongoing electrical problems continued to plague them, taking them out of the running then finally leading to retirement after midnight – with no lights! Further excitement in the night happened when the Pozzi Delahaye had an engine-fire while refuelling, right in front of the second-placed Mairesse Talbot in at the same time.[13] But once the flames were out, Flahault jumped in and drove out without even checking for damage[12]

Early on Sunday morning while running second, the Allard’s 3-speed gearbox lost its two lowest gears. It could not be repaired, so the mechanics jammed it into 3rd and sent it back out again, having dropped down to 8th. Around a similar time the differential on Chinetti’s Ferrari started playing up, after also running in the top 3 for first half of the race; they eventually retired mid-morning.

At the halfway point after 12 hours, it was the two Talbots of Rosier and Meyrat/Mairesse (six laps apart), then a lap back to the Johnson/Hadley Jaguar, the Rolt/Hamilton Nash-Healey and the struggling Allard.[12]

Morning

At 5am the leader came into the pits with a 7-lap lead, and Rosier personally replaced the rocker-shaft. His son then took the car out for just 2 laps while Louis cleaned up and ate some bananas. Then Rosier Sr got back in, resuming in 3rd, and drove on for the rest of the race.[14] With Rosier in the pits, the second Talbot took the lead and held it for three hours, with the Jaguar of Johnson/Hadley in second. But Rosier was a man on a mission and before 9am, he had overtaken both and was back in the lead. He had to pit later in the morning when he struck an owl, smashing the (tiny) windscreen and giving him a black eye.[15]

At 8am Jean Lucas, running sixth, crashed and rolled Lord Selsdon’s Ferrari, getting minor injuries and taking the last of the prancing horses out of the race. The Anglo-American Nash-Healey prototype of Rolt/Hamilton had been in the top-5 since halfway and was 3rd when it was punted off the track by Louveau’s Delage. The 45 minutes spent on repairs dropped it a position. Pozzi’s Delahaye had run as high was 5th through the night, but then the fire and subsequent overheating dropped it down. Late in the morning at a pit-stop, pent-up pressure blew off the radiator cap, which the officious stewards deemed an illegal breakage of the security seals and controversially disqualified him.

By midday the old order was restored: the two Talbots, now only a lap apart, three laps back to the Jaguar and a further lap to the Nash-Healey. Rosier eased off, conserving his car, but keeping a solid lead. Then the Jaguar of Johnson/Hadley had to retire with less than 3 hours to go when the clutch finally let go, after the drivers had had to use engine-breaking because of a lack of brakes. But it was Tim Cole who was lapping fastest of all in fourth, even though he still only had top gear, and caught Rolt (having to driver carefully with a dodgy rear axle and fading brakes) with 30 minutes to go.

Finish and post-race

In the end, Louis Rosier cruised to the win, and with Guy Mairesse and Pierre Meyrat, gave one of Talbot-Lago’s greatest days – coming 1st & 2nd (in fact, all 3 cars finished - the sedan was 13th), and a record distance covered[16] All the first five finishers beat the 1939 distance record[16] It was also a great race for the British cars with 14 of 16 entered finishing, taking the 8.0L, 3.0L, 2.0L and 1.5L class wins. The Allard finished third, the Nash-Healey was fourth ahead of two of John Wyer’s Aston Martins that had run like clockwork. They were comfortably ahead of Louveau’s Delage in seventh, that had finished 2nd the year before but this year never had the pace, despite running trouble-free. The new Frazer-Nash (driven by ex-fighter pilot Dickie Stoop) took the S2000 class and the lightened works Jowett Javelin roadster easily won the S1500 class by 12 laps, driven by the coincidentally-named Wise and Wisdom.

By contrast all five Ferraris retired, as did all nine Simca-engined cars, including the six works Gordinis. Both the Bentleys finished – though Louis Rosier did a herculean job driving for all but 2 laps, Eddie Hall in the TT finished 8th and became the only driver to finish a Le Mans going solo the whole distance (just over 3200km).[2] Likewise both Cadillacs finished (10th & 11th – positions they had held virtually the whole race) even though ‘’Le Monstre’’, like the Allard, had been stuck in top gear for most of the race[6] The little Czech Aero repeated its win from 1949 in the smallest (S750) class, beating the French contingent it went up against.

The Abecassis/Macklin Aston Martin had taken the lead in the Index of Performance in the morning, but a strong drive in their little Monopole-Panhard #52 (611cc, 36bhp) by company owners Pierre Hérnard & Jean de Montrémy meant they exceeded their designated distance by exactly the same margin thereby sharing the Index victory.[14][16]

The Jaguar management were satisfied with the performance of their cars – two finished, and the other had run as high as second before retiring, but resolved to fix the brake problems that had troubled all three cars through the race

Tragically, the great French racer, Raymond Sommer would not get to enjoy his retirement – he was killed later in the year, at a Formula 2 race at Cadours. [17]

Official results

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S 5.0 |

5 | (private entrant) |

Talbot-Lago T26 GS Biplace | Talbot-Lago 4.5L S6 | 256 | |

| 2 | S 5.0 |

7 | (private entrant) |

Talbot-Lago T26 Monoplace Decalee |

Talbot-Lago 4.5L S6 | 255 | |

| 3 | S 8.0 |

4 | Allard J2 | Cadillac 5.4L V8 | 251 | ||

| 4 | S 5.0 |

14 | Nash-Healey E | Nash 3.8L S6 | 250 | ||

| 5 | S 3.0 |

19 | Aston Martin DB2 | Aston Martin 2.6L S6 | 249 | ||

| 6 | S 3.0 |

21 | Aston Martin DB2 | Aston Martin 2.6L S6 | 244 | ||

| 7 | S 3.0 |

18 | (private entrant) |

Delage D6-3L | Delage 3.0L S6 | 241 | |

| 8 | S 5.0 |

11 | (private entrant) |

Bentley Corniche TT Coupé | Bentley 4.3L S6 | 236 | |

| 9 | S 2.0 |

30 | (private entrant) |

Frazer Nash Milla Miglia | Bristol 2.0L S6 | 235 | |

| 10 | S 8.0 |

3 | (private entrant) |

Cadillac Coupe de Ville | Cadillac 5.4L V8 | 233 | |

| 11 | S 8.0 |

2 | (private entrant) |

Cadillac Spider | Cadillac 5.4L V8 | 232 | |

| 12 | S 5.0 |

15 | (private entrant) |

Jaguar XK120S | Jaguar 3.4L S6 | 230 | |

| 13 | S 5.0 |

6 | (private entrant) |

Talbot-Lago Gran Sport Coupe | Talbot-Lago 4.5L S6 | 228 | |

| 14 | S 5.0 |

12 | (private entrant) |

Bentley 4¼ Paulin | Bentley 4.3L S6 | 225 | |

| 15 | S 5.0 |

16 | (private entrant) |

Jaguar XK120S | Jaguar 3.4L S6 | 225 | |

| 16 | S 1.5 |

36 | Jowett Jupiter Javelin | Jowett 1486cc Flat-4 | 220 | ||

| 17 | S 3.0 |

22 | (private entrant) |

Riley RMC | Riley 2.5L S4 | 213 | |

| 18 | S 1.5 |

39 | (private entrant) |

MG TC Special | MG 1244cc S4 | 208 | |

| 19 | S 3.0 |

23 | (private entrant) |

Healey Elliott | Riley 2.4L S4 | 203 | |

| 20 | S 2.0 |

31 | (private entrant) |

Frazer Nash High Speed Le Mans Replica |

Bristol 2.0L S6 | 201 | |

| 21 | S 750 |

51 | Aero Minor 750 | Aero 744cc Flat-2 (2-Stroke) |

184 | ||

| 22 | S 750 |

52 | Monopole X84 | Panhard 611cc Flat-2 | 180 | ||

| 23 | S 750 |

58 | DB Sport | Panhard 611cc Flat-2 | 175 | ||

| 24 | S 1.1 |

46 | (private entrant) |

Renault 4CV | Renault 760cc S4 | 171 | |

| 25 | S 1.1 |

48 | (private entrant) |

Renault 4CV | Renault 760cc S4 | 170 | |

| 26 | S 750 |

55 | (private entrant) |

Panhard Dyna X84 Sport | Panhard 611cc Flat-2 | 168 | |

| 27 | S 1.1 |

45 | (private entrant) |

Renault 4CV | Renault 760cc S4 | 158 | |

| 28 | S 750 |

56 | (private entrant) |

Callista RAN D120 | Panhard 611cc Flat-2 | 153 | |

| 29 | S 750 |

57 | (private entrant) |

Panhard Dyna X84 | Panhard 611cc Flat-2 | 151 |

Did Not Finish

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Laps | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | S 5.0 |

17 | (private entrant) |

Jaguar XK120S | Jaguar 3.4L S6 | 220 | Clutch | |

| 31 | S 5.0 |

8 | Delahaye 175S | Delahaye 4.5L S6 | 165 | Disqualified Water leak | ||

| 32 | S 2.0 |

28 | (private entrant) |

Ferrari 166 MM Berlinetta LM | Ferrari 2.0L V12 | 164 | Accident | |

| 33 | S 1.1 |

43 | Gordini T15S | Simca 1090cc S4 | 157 | Engine | ||

| 34 | S 1.1 |

41 | (private entrant) |

Gordini T11 MM | Simca 1090cc S4 | 143 | Accident | |

| 35 | S 750 |

49 | (private entrant) |

Aero Minor | Aero 744cc Flat-2 (2-Stroke) |

139 | Wheel bearing | |

| 36 | S 1.1 |

40 | (private entrant) |

Simca Huit | Simca 1090cc S4 | 126 | Engine | |

| 37 | S 3.0 |

24 | Ferrari 195 S Barchetta | Ferrari 2.3L V12 | 121 | Transmission | ||

| 38 | S 5.0 |

10 | Delettrez |

Delettrez Diesel | Delettrez 4.4L S6 (Diesel) |

120 | Engine | |

| 39 | S 1.1 |

44 | Škoda 1101 Spyder | Škoda 1089cc S4 | 120 | Engine | ||

| 40 | S 750 |

54 | (private entrant) |

Panhard Dyna X84 Sport | Panhard 611cc Flat-2 | 115 | Electrics | |

| 41 | S 3.0 |

33 | Gordini T15S Coupé | Simca 1491cc supercharged S4 |

95 | Engine | ||

| 42 | S 1.1 |

47 | (private entrant) |

Renault 4CV | Renault 760cc S4 | 92 | Accident | |

| 43 | S 750 |

53 | (private entrant) |

Monopole X84 | Panhard 611cc Flat-2 | 89 | Oil leak | |

| 44 | S 750 |

50 | (private entrant) |

Ferry Sport | Renault 747cc S4 | 86 | Engine | |

| 45 | S 3.0 |

25 | Ferrari 195 S Berlinetta | Ferrari 2.3L V12 | 82 | Electrics | ||

| 46 | S 1.1 |

42 | Gordini T15S | Simca 1090cc S4 | 77 | Oil pump | ||

| 47 | S 1.5 |

37 | (private entrant) |

Fiat 1500 Spéciale | Fiat 1.5L S4 | 75 | Gearbox | |

| 48 | S 1.5 |

35 | Gordini T15S | Simca 1491cc S4 | 50 | Engine | ||

| 49 | S 2.0 |

64 | DB 5 | Citroën 1.9L S4 | 44 | Engine | ||

| 50 | S 2.0 |

26 | (private entrant) |

Ferrari 166 MM | Ferrari 2.0L V12 | 44 | Clutch | |

| 51 | S 5.0 |

1 | d'Armes de Paris |

M.A.P. Diesel | M.A.P. 5.0L supercharged Flat-4 (Diesel) |

39 | Overheating | |

| 52 | S 3.0 |

32 | Gordini T15S Coupé | Simca 1491cc supercharged S4 |

34 | Water radiator | ||

| 53 | S 1.1 |

63 | (private entrant) |

Renault 4CV | Renault 760cc S4 | 32 | Electrics | |

| 54 | S 2.0 |

27 | (private entrant) |

Ferrari 166 MM Coupé | Ferrari 2.0L V12 | 25 | Out of fuel | |

| 55 | S 750 |

60 | Simca Six Spéciale | Simca 580cc S4 | 20 | Out of fuel | ||

| 56 | S 1.5 |

34 | Gordini T15S | Simca 1491cc S4 | 14 | Gearbox | ||

| 57 | S 1.1 |

66 | (private entrant) |

Simca Huit Spéciale | Simca 1087cc S4 | 13 | Engine | |

| 58 | S 3.0 |

20 | Aston Martin DB2 | Aston Martin 2.6L S6 | 8 | Engine | ||

| 59 | S 750 |

59 | DB Sport | Panhard 611cc Flat-2 | 6 | Accident | ||

| 60 | S 5.0 |

9 | Delahaye 175S | Delahaye 4.5L S6 | 0 | Battery |

16th Rudge-Whitworth Biennial Cup (1949/1950)

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S 750 |

52 | Monopole X84 | 1.276 | ||

| 2 | S 2.0 |

30 | (private entrant) |

Frazer Nash Milla Miglia | 1.246 | |

| 3 | S 750 |

51 | Aero Minor 750 | 1.221 | ||

| 4 | S 750 |

55 | (private entrant) |

Panhard Dyna X84 Sport | 1.195 |

Statistics

- Fastest Lap in practice – Raymond Sommer, #25 Ferrari 195 S – 5:00, 161.90 km/h (100.60 mph) [18]

- Fastest Lap – Louis Rosier #5 Talbot-Lago T26C GS Biplace – 4:53.5, 165.49 km/h (102.83 mph)

- Winning Distance – 3465.12 km (2153.12 miles)

- Winner’s Average Speed – 144.38 km/h (89.72 mph)

Trophy winners

- 16th Rudge-Whitworth Biennial Cup – #52 Pierre Hérnard / Jean de Montrémy

- Index of Performance – #19 Abecassis / Macklin & #52 Hérnard / de Montrémy (tied)

Notes

- Laban 2001, p. 104.

- Spurring 2011, p. 54.

- Spurring 2011, p. 53.

- Clausager 1982, p. 79

- Laban 2001, p .105.

- Spurring 2011, p. 64.

- Laban 2001, p. 106.

- Spurring 2011, p. 62.

- Clausager 1982, p. 80

- Spurring 2011, p. 70.

- Motor 1950.

- Road & Track 1950.

- Autocar 1950.

- Spurring 2011, p. 54.

- Spurring 2011, p. 56.

- Moity 1974, p. 42.

- The Motor 1951, p. 179.

- Spurring 2011, p. 375.

References

- Spurring, Quentin (2011) Le Mans 1949-59 Sherborne, Dorset: Evro Publishing ISBN 978-1-84425-537-5

- Clausager, Anders (1982) Le Mans London: Arthur Barker Ltd ISBN 0-213-16846-4

- Laban, Brian (2001) Le Mans 24 Hours London: Virgin Books ISBN 1-85227-971-0

- Moity, Christian (1974) The Le Mans 24 Hour Race 1949-1973 Radnor, Pennsylvania: Chilton Book Co ISBN 0-8019-6290-0

- Pomeroy & Walkerley - editors (1951) The Motor Year Book 1951 London: Temple Press ISBN 1-85520-357X –

- Clarke, R.M. - editor (1997) Le Mans 'The Jaguar Years 1949-1957' Cobham, Surrey: Brooklands Books ISBN 1-85520-357X – republishing the original reports from ‘’The Motor’’ and ‘’Autocar’’ of June/July 1950, and ‘’Road & Track’’ (Sept ‘50)

External links

- Racing Sports Cars – Le Mans 24 Hours 1950 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Le Mans History – Le Mans History, hour-by-hour (incl. pictures, YouTube links). Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Formula 2 – Le Mans 1950 results & reserve entries. Retrieved 22 July 2016.