1931 24 Hours of Le Mans

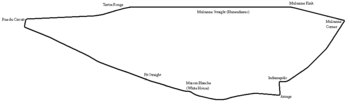

The 1931 24 Hours of Le Mans was the 9th Grand Prix of Endurance that took place at the Circuit de la Sarthe on 13 and 14 June 1931.

| 1931 24 Hours of Le Mans | |

| Previous: 1930 | Next: 1932 |

| Index: Races | Winners | |

With the demise of Bentley, the favourite for an outright victory was split between the Bugatti and Alfa Romeo works teams, with a lone privateer Mercedes as an outside chance. Once again it was one of the smaller fields, with only 26 starters.

At the start of the race it was the Mercedes setting the pace from the Bugattis of Chiron and Divo. But tyre-wear was a big issue, with many cars suffering tyre blowouts and punctures. This left Marinoni leading in the works Alfa. Coming up to the first refuelling stops, the rear tyre on Maurice Rost’s Bugatti at full speed on the Mulsanne Straight. The car careered through a fence and knocked down three spectators, killing one. When more tyre delaminations plagued Chiron’s Bugatti the team withdrew the remaining two cars. Tyre troubles had cost the Mercedes team eight laps.

The Alfa Romeo of British privateers Howe and Birkin had been having a reliable race. As others were delayed they caught them up and took the lead after midnight. At 2.30am a sudden thunderstorm swept the track. Zehender went off at Indianapolis doing damage that eventually forced the works Alfa’s retirement in the morning. The Talbots of the British Fox & Nicholl team were running third and fourth with the Mercedes closing in again. Ivanowski was able to source some Dunlop tyres. He and Stoffel were able to pick up their pace, and when the leading Talbot was waylaid in the morning by chassis damage, the Mercedes was up to second by noon.

At the finish, Howe and Birkin won by seven laps from the Mercedes and the remaining Talbot. This was the first win at Le Mans for an Italian car, and in a record-breaking run, they claimed all three trophies – including the Index and Biennial Cup – and broke the 3000km distance for the first time. Only six cars were classified, which has been the lowest ever number of finishers in the 24-Hour race.

Regulations

This year there were no changes to the racing regulations of either the AIACR (forerunner of the FIA) Appendix C rules, nor those of the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO). The biggest change this year was in the pits. Rather than refuelling with 10-litre cans, a series of 4-metre high reservoir towers were built holding 1000-litres. Three hoses from each allowed gravity-replenishment at about 250 litres per minute. Shell once again had the fuel contract and again offered its three standard fuel options. The ACO also now allowed a mechanic to assist the driver with the refuelling.[1]

As usual, as engine power advanced, the ACO once again adjusted the Index target distances. Example targets included the following:[2]

| Engine size |

1930 Minimum distance |

1931 Minimum distance |

Equivalent laps |

Minimum vehicle weight |

Ballast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6000cc+ | 2,500 km (1,600 mi) | 2,600 km (1,600 mi) | 158.9 laps | 1820 kg | 180 kg |

| 3000cc | 2,350 km (1,460 mi) | 2,390 km (1,490 mi) | 146.1 laps | 875 kg | 120 kg |

| 1500cc | 2,132 km (1,325 mi) | 2,260 km (1,400 mi) | 138.1 laps | 670 kg | 120 kg |

| 1100cc | 2,000 km (1,200 mi) | 2,100 km (1,300 mi) | 128.4 laps | 430 kg | 60 kg |

| 750cc | 1,825 km (1,134 mi) | 1,785 km (1,109 mi) | 109.1 laps | 430 kg | 60 kg |

Entries

With Bentley in major financial strife, the works team had been disbanded and the Bentley Boys dispersed, marking the end of an era. Into this void came works teams from the two main powerhouses of current Grand Prix racing: Alfa Romeo and Bugatti. However, apart from Aston Martin, and a (non-eventuating) effort from Ariès the remaining entries were from privateer teams and “gentleman-drivers”. There were still only 30 cars entered, not a great improvement on the record low number from the previous year. Of those, only four were entered in the final of the Biennial Cup – an Alfa Romeo, the two Talbots and the returning women in their Bugatti.[3][4]

| Category | Entries | Classes |

|---|---|---|

| Large-sized engines | 17 / 15 | over 2-litre |

| Medium-sized engines | 7 / 5 | 1.1 to 2-litre |

| Small-sized engines | 6 / 6 | up to 1.1-litre |

| Total entrants | 30 / 26 | |

- Note: The first number is the number of entries, the second the number who started.

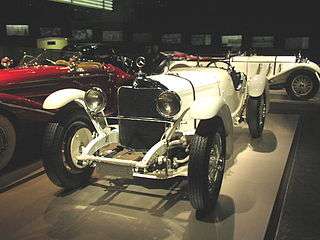

Daimler-Benz had pulled out of racing officially in 1930 leaving privateers to run their cars. In the 1930 race, the Mercedes of Rudolf Caracciola had taken the challenge to Bentley in the first half of the race. This year, Paris-based Russian Valériani-Vladimir Tatarinoff, entered an SSK (Super Sports Kurz) on behalf of fellow émigré Count Boris Ivanowski. He had previously been denied an entry of a stripped-down Alfa Romeo for the 1928 race. The SSK had a big 7.1-litre engine that could be augmented temporarily by a Roots supercharger up to 250 bhp.[5] Along with his co-driver, Le Mans veteran Henri Stoffel, Ivanowski entered the car in both touring and Grand Prix races.[6]

Bugatti had run almost exclusively in Grand Prix racing with great success in the late 1920s. This year marked its first foray to Le Mans with a works team. The new Type 50 was a development of the big-engined Type 46. Its 5.0-litre straight-8 engine had a Roots supercharger and was capable of 250 bhp, and with a 3-speed gearbox, gave the car a top speed of 195 kp/h (120 mph). The team, managed by Bugatti’s 22-year old son Jean, brought three short-wheelbase versions for their works drivers Louis Chiron / Achille Varzi and Albert Divo/Guy Bouriat, joined by Maurice Rost/Caberto Conelli.[5][7] Perhaps anticipating bad weather, they were running on a new, heavy-tread Michelin tyre.[4] Other innovations were a new quick-change brake system, “pop-top” petrol caps, and oil-refill tubes in the bonnet all designed to speed up pitwork.[8] Alongside the works team were three French privateer entries in smaller Bugattis, including wealthy Parisian bankers Pierre Louis-Dreyfus / Antoine Schumann who raced together under the pseudonyms “Ano-Nime”; and the women who charmed the media the previous year, Odette Siko and Marguerite Mareuse, returned.[9]

.jpg)

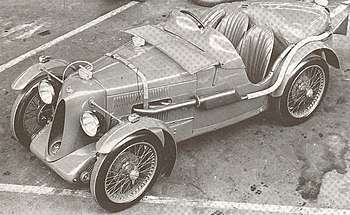

Alfa Romeo had achieved great success in recent years with the 6C model, in both its regular or supercharged format. Vittorio Jano’s new design, the 8C, had a supercharged 2.3-litre engine that developed 155 bhp. It came in two styles: a short-wheelbase, 2-seater corto adapted for Grand Prix racing and narrow, tight circuits like the Mille Miglia; and a 4-seater lungo (long) version for the ACO regulations for touring cars. Although the Scuderia Ferrari ran the car for Italian races, it was a works team that arrived at Le Mans with two cars. The driver-pairings were team regulars Giuseppe Campari / Attilio Marinoni and “Nando” Minoia / ”Freddy” Zehender.[10] Two Englishmen were some of the early purchasers of the new model. Sir Henry “Tim” Birkin had given up his Blower Bentley project for the more reliable Alfa, and won his class first time up at the Irish Grand Prix the week before Le Mans. Earl Francis Howe had his delivered to replace his 6C that Achille Varzi had crashed in the 1930 Irish race. So in the 1930 Le Mans, Howe had run his Mercedes-Benz instead, earning one of the four entries taken up for the Biennial Cup. For this race, he approached Birkin to be his co-driver[10] The Bentley 4½ Litre that Birkin had raced in 1928 (and then Earl Howe in 1929) had been purchased Anthony Bevan who bought it back for a third run at Le Mans.[11] Since the previous race, the great brand had been sold to Rolls-Royce.[12]

Unlike most other car companies, Talbot had been reasonably successful with sales of its 6-cylinder car range. Its latest version, the 105, now had a 3-litre capable of 120 bhp and 175 kp/h (110 mph), as well as a 4-speed gearbox and a bigger 160-litre fuel-tank. Four cars were made available to the Fox & Nicholl team. Two were taken to Le Mans to race with another as a test vehicle. The drivers were team-regulars Brian Lewis, Baron Essendon / Johnny Hindmarsh and Tim Rose-Richards / Owen Saunders-Davies.[13]

Henri de Costier had driven at Le Mans three times in the late-’20s. This year he organised the entry of a pair of big Chrysler straight-8s. He, himself, drove the larger 6.3-litre, 125 bhp, CG Imperial Eight while the new model CD Eight (with a 100 bhp 3.9-litre engine) was entrusted to the new, young French talent, Raymond Sommer.[14]

La Lorraine-Dietrich had not competed at Le Mans since 1926, after the company believed they were denied victory in the Biennial Cup by the ACO on a technicality. The team’s four B3-6 Le Mans specials had been mothballed until one was sold to Henri Trébor, who got the car a few days before the race after a factory refit. Racing journalist Roger Labric submitted an entry on his behalf. Trébor engaged Louis Balart as his co-driver, himself a veteran of the first four Le Mans races.[15] The small Scottish car company of Arrol-Aster arrived for its only foray at the race. The 17/50 had a 2.4-litre sleeve-valve engine with a Cozette supercharger. The car was prepared at Tim Birkin’s race-garage in London.[16][7]

Aston Martin returned to Le Mans after a three-year hiatus with a works team of three cars. The 1.5-litre International was still in a limited run and only seven racing chassis had been made. Le Mans winner Sammy Davis was in hospital after a major accident at Brooklands at Easter so company engineer Augustus “Bert” Bertelli instead drove with Maurice Harvey. Former Lea-Francis drivers Kenneth Peacock and Sammy Newsome had the second car while Jack Bezzant and Humphrey Cook had the third.[17]

Voiturette racing was still popular and encouraged enthusiast engineers to make their own small customised specials. Yves Giraud-Cabantous was one such. A mechanic and driver at Salmson, he adapted a Salmson chassis with the oft-used 1.1-litre Ruby engine that put out 35 bhp. After successes in the Bol d’Or, Roger Labric encouraged him to enter the Le Mans race and offered to enter two under his name.[18] After a disappointing race for BNC the previous year, when the new car didn’t even turn a wheel, the team returned with the tried and tested 527 Sport, also with a Ruby engine.[19]

In 1930 George Eyston had approached Cecil Kimber, managing director of MG Cars, about developing the first 750cc car to break the 100mph barrier. In part, this was because his Land Speed Record rival, Malcolm Campbell was working with Austin for the same goal. With the resulting EX120 special, Eyston achieved the record in February 1931 at Montlhéry.[20] Using the prototype’s engine and frame, MG built the new C-Type. Fourteen cars, already pre-sold, were quickly built in time to take a clean sweep, first time out, at the Brooklands Double-12 (Britain’s annual 24-hour event) in May. The result was repeated a month later at the Irish Grand Prix. A week later, two of the cars were entered for Le Mans, without superchargers. Sir Francis Samuelson returned with his regular co-driver Fred Kindell, while Lady Joan Chetwynd ran her husband’s car along with fellow C-Type owner Henry Stisted.[20]

Practice

A number of teams and drivers were racing the weekend before at events across Europe, which made preparations difficult. Arthur Fox, in one of his Talbots, gave Alfa drivers Birkin, Howe and Campari a lift to London from Dublin where they had all been racing in the Irish Grand Prix meeting.[21]

After their races the Bugatti team drove their cars across from Molsheim in eastern France, arriving on Thursday. In practice, one of the cars blew a rear tyre, so team manager “Meo” Costantini directed the drivers to not go above 4000rpm to limit their top speed for the first six hours.[5]

Through practice, the Alfa Romeos had engine ignition problems because of the hybrid fuel being used. This had happened the year before to Birkin and his “Blower Bentleys”. His solution then was to switch to pure benzole and change out the pistons. Parts were delayed coming from the factory in Milan, the mechanics worked through the night but by race morning only three of the cars were ready. Team manager Aldo Giovannini stood down Campari and Minoia and instead teamed up Marinoni (as a very competent mechanic in his own right) with Zehender.[22][23][4]

The ACO celebrated its Silver Jubilee, formed in 1906 running the first French Grand Prix. Special guests at the Saturday luncheon included Ferenc Szisz and Felice Nazzaro who had finished first and second respectively at that inaugural event. ACO Club secretary, Georges Durand, had also served 25 years and was the honorary starter for the race on a hot, sunny Saturday afternoon.[1][8]

Race

Start

First away from the flagfall at 4pm were the two Chryslers, however their lead was short-lived and with the big cars’ sluggish acceleration out of the Pontlieue corners,[14] they were overtaken by the works Bugattis of Chiron and Divo.[8] Henri Stoffel wound up the Mercedes’ supercharger and quickly blasted past all four of them into the lead– Chiron failed his breaking at Mulsanne on lap 3 trying to outbrake him and ended up down the escape road.[5] The two Alfas, and the Bugattis of Rost and Louis-Dreyfus filled out the top-9.[1][8] A bit further back the three Aston Martins were jockeying with the Lorraine while the Chryslers slipped back.[8]

After an hour though, by lap ten, it was all change. Birkin had just come in with a misfiring sparkplug when both Stoffel and Chiron arrived with flat tyres. This put Marinoni’s Alfa in the lead, followed by the Bugattis of Divo and Rost. In his race back up the field Chiron had a big moment halfway down the Hunaudières straight. Having just overtaken Birkin, the other rear tyre blew at top speed putting him in a wild slide. With skill, he regained control and managed to get the car slowly back to the pits.[1][7][8]

The two Chryslers were the first retirements. Sommer was out after 14 laps with a holed radiator, and then five laps later, into the pits came Costier with the same problem.[14] At 6.30pm Marinoni had just finished his 20th lap, leading from Divo but Rost, running third, did not come around. He had been going down the back straight at 175 kp/h when a tyre blew. The car crashed through the roadside fence and trees. Three men standing in the spectator-prohibited zone were run down and one, Jules Bourgoin, was killed while the other two were seriously injured. Rost had been thrown from the car and suffered head injuries and a broken shoulder and ribs.[24][7][25]

So, after three hours, at the first round of pit-stops, Divo led from Marinoni and Stoffel, having all done 23 laps. Chiron was a lap behind with the two Talbots. [25] Chiron then pitted with a third delaminated tyre. Bouriat, who had just taken over from Divo was called in soon after while leading and both remaining works Bugattis were withdrawn, despite boos from the spectators.[26][23][7][27]

This left the Mercedes to battle the Alfa Romeos. But when tyre-delaminations struck them twice, the drivers decided to ease back and change tyres every hour to avoid further issues.[6] These delays cost the Mercedes eight laps.[26] The Talbots’ reliability kept them in touch with the leaders, only doing their first pit-stops at 8pm, four hours into the race.[27] It was unknown why Odette Siko bought her Bugatti in for its second stop after 38 laps, but when the team refuelled it two laps before regulations allowed, they were disqualified.[9]

Night

As dusk fell, Couper’s Bentley broke its crankcase just as he was braking for the corners at Pontlieue. The driver managed to stop just in front of the barriers blocking the main road into Le Mans[11][27] Going into the night, Marinoni/Zehender were still leading. At the 6-hour mark (10pm) they had done 46 laps. Howe and Birkin were closing in quickly, eventually overtaking them after midnight. Just a lap back was the Talbot of Rose-Richards/Saunders-Davies while the Lewis/Hindmarsh sister-car had been delayed by electrical issues and now three laps behind them with the Mercedes half a lap further back.[27][26] The three Astons were also still running together inside the top-10: Bezzant/Cook in 6th (40 laps) and Bertelli/Harvey in 7th. However the team had replaced their headlamps with heavier Zeiss headlamps. The strain from the roads gradually shook the bolts loose and all the Aston Martins lost time getting them re-secured.[17][27][28] The Caban of Labric/Giraud-Cabantous got beached at Pontlieue after midnight, losing much time getting dug out.[18][27]

Then at 2.30am, a violent lightning flash and thunderclap heralded a short intense squall that flooded the track for an hour.[22][27] Cars quickly came into the pits to raise wind-screens and put on wet-weather gear. But on his out-lap, Zehender aquaplaned off at Indianapolis corner, slamming the front corner. It got repaired and back on the road, but lost four laps.[22][27] The two Fox & Nicholl Talbots were still running reliably in third and fourth – their only issues were similar to the Aston Martins. Both cars each had one of their headlamp brackets brake. The drivers latched onto faster cars, using them as spotters through the night on the dark roads.[21]

Morning

As dawn broke nearly half the field had retired or been withdrawn. Howe and Birkin had done 92 laps, four laps ahead of Marinoni/Zehender with the two Talbots a further two laps back.[27] Not long after 6am the rear-axle broke on the works Alfa in second, forcing its retirement.[26] The MG of Samuelson/Kindell smacked an earth-bank avoiding another car. They lost three-quarters an hour fixing the suspension.[20] Ivanowski was able to get hold of some Dunlop tyres to replace his problematic Engleberts. With the supercharger running, he was soon putting in very quick times, setting the fastest lap of the race.[27] He was able to overhaul one of the Talbots and got a lap back off the leaders. At 9am, the Bezzant/Cook Aston Martin still running in fifth broke a front-wing support and the wing fell off. Without parts no repairs were possible, and the car was retired.[17]

Around 9.30am, Lewis noticed the Talbot’s rear fueltank shifting on the chassis. Pitting, the team found the frame had cracked just above the rear axle. Despite twenty minutes of repairs (using belts and straps to tie the tank in place) and three more laps, it was still dangerously loose, and the car had to be retired. The metal fatigue was put down to the combined strain from this race and the recent Brooklands Double-12 it had run in. [21][27] This moved the Mercedes up into second, a place it held for the rest of the race. The two little Cabans had quietly kept circulating at a regular rate at the tail of the field, designed to get them to their target distance. But during the morning, Caban’s car came to a stop on the Mulsanne straight with fuel-feed issues.[18]

Going into the afternoon there were only nine cars left running. The last Bugatti had just retired – the privateer entry of Jean Sébilleau lost its failing clutch.[9] Although the privateer Alfa had a sizeable lead over the Mercedes, they were not able to ease off, as the Talbot (in third) kept up the pressure for honours in the Index and Biennial Cup handicap competitions.[22]

Finish and post-race

In the end, the hard driving by Howe and Birkin gave them a comfortable seven-lap victory, and they were only the second crew to win all three prizes: outright distance, Index and the Coupe Bienniale. It was Birkin’s second win after his victory in 1929 with Bentley. They also gave Italy its first win in the endurance event, earning personal congratulations from Mussolini.[7] Their total distance covered broke the 3,000 km (1,900 mi) barrier for the first time.[7]

The Mercedes lasted the distance, finishing four laps ahead of the Talbot of Rose-Richards/Saunders-Davies. Fourth, 23 laps further back, was the old Lorraine-Dietrich. It had spent most of the race mixing it with the Aston Martins, with newer engines half its size. In the end it covered two more laps, but 100km less, than its stable-mate that had won the 1926 race.[15]

The remaining two Aston Martins had varying stories: Peacock & Newsome retired with less than two hours to go because of bodywork issues while the other, after the assorted delays, had to hurry on to make its target distance. “Bert” Bertelli and Maurice Harvey made it by just one lap, finishing fifth and winning the 1500cc class. The little Caban of Vernet/Vallon was the final classified car, just meeting its target by bare metres and over 900km behind the winner. The meagre six finishers being the lowest number in the history of the race.[26][7]

The hard-luck story was the Samuelson/Kindell MG. With just over an hour to go, a conrod broke. The team isolated the affected cylinder and parked the car to rejoin the race just before 4pm to complete a final, careful lap. Regulations stipulated the last lap had to be done within 30 minutes but when Samuelson took 32 minutes to complete it they were left unclassified.[20][4]

Alfa Romeo developed the successful 8C-2300 into a shorter, Grand-Prix version developing 180 bhp. After a great win in the year’s 10-hour Italian Grand Prix, it gained the “Monza” moniker.[22] Bugatti instead chose to mothball their Type 50s, to concentrate on the more successful Type 51, while the engines were fitted to the new Type 54.[24] In a busy month after the race, Ivanowski and Stoffel took the Mercedes successively to the 10-hour French Grand Prix (DNF), Spa 24 Hours (DNF) and Belgian Grand Prix (5th).[6]

Official results

Finishers

Results taken from Quentin Spurring's book, officially licensed by the ACO[29] Class Winners are in Bold text.

| Pos | Class | No. | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Tyre | Target distance* |

Laps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.0** | 16 | (private entrant) |

Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 LM | Alfa Romeo 2.3L S8 supercharged |

D | 147 [B] | 184 | |

| 2 | 8.0 | 1 | (private entrant) |

Mercedes-Benz SSK | Mercedes-Benz 7.1L S6 supercharged |

E D |

159 | 177 | |

| 3 | 3.0 | 11 | Talbot AV105 | Talbot 3.0L S6 | D | 146 [B] | 173 | ||

| 4 | 5.0 | 9 | Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6 Le Mans | Lorraine-Dietrich 3.4L S6 | D | 148 | 150 | ||

| 5 | 1.5 | 25 | Aston Martin International | Aston Martin 1495cc S4 | D | 138 | 139 | ||

| 6 | 1.1 | 29 | Caban Spéciale | Ruby 1097cc S4 | D | 128 | 128 | ||

| N/C*** | 750 | 31 | (private entrant) |

MG Midget C-type | MG 746cc S4 | D | 109 | ? |

Did Not Finish

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Tyre | Target distance* |

Laps | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNF | 3.0 | 10 | Talbot AV105 | Talbot 3.0L S6 | D | 146 [B] | 132 | Chassis (18 hr) | ||

| DNF | 1.5 | 26 | Aston Martin International | Aston Martin 1495cc S4 | D | 138 | 126 | Bodywork (22 hr) | ||

| DNF | 1.5 | 24 | Aston Martin International | Aston Martin 1495cc S4 | D | 138 | 111 | Bodywork (18 hr) | ||

| DSQ | 1.1 | 27 | (private entrant) |

B.N.C. Type 527 Sport | Ruby 1097cc S4 | D | 128 | 111 | Premature refuelling (21 hr) | |

| DNF | 3.0** | 14 | Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM | Alfa Romeo 2.3L S8 supercharged |

D | 147 | 99 | Transmission (14 hr) | ||

| DNF | 1.5 | 23 | (private entrant) |

Bugatti Type 37 | Bugatti 1496cc S4 | D | 138 | 96 | Transmission (21 hr) | |

| DNF | 5.0** | 12 | (private entrant) |

Arrol-Aster 17/50 | Arrol-Aster 2.4L S6 supercharged |

D | 148 | 95 | Electrics (16 hr) | |

| DNF | 1.1 | 28 | Caban Spéciale | Ruby 1097cc S4 | D | 128 | 89 | Engine (18 hr) | ||

| DSQ | 1.5 | 22 | (private entrant) |

Bugatti Type 40 | Bugatti 1496cc S4 | E | 138 [B] | 45 | Premature refuelling (5 hr) | |

| DNF | 1.1 | 30 | (private entrant) |

Lombard AL3 | Lombard 1097cc S4 | D | 128 | 45 | Engine (6 hr) | |

| DNF | 750 | 32 | (private entrant) |

MG Midget C-type | MG 746cc S4 | D | 109 | 30 | Engine (8 hr) | |

| DNF | 5.0 | 7 | (private entrant) |

Bentley 4½ Litre | Bentley 4.4L S4 | D | 156 | 29 | Engine (6 hr) | |

| DNF | 8.0** | 5 | Bugatti Type 50S | Bugatti 5.0L S8 supercharged |

M | 159 | 26 | Withdrawn (4 hr) | ||

| DNF | 8.0** | 4 | Bugatti Type 50S | Bugatti 5.0L S8 supercharged |

M | 159 | 24 | Withdrawn (4 hr) | ||

| DNF | 3.0** | 19 | (private entrant) |

Bugatti Type 43 | Bugatti 2.3L S8 supercharged |

D | 147 | 22 | Transmission (3 hr) | |

| DNF | 8.0** | 6 | Bugatti Type 50S | Bugatti 5.0L S8 supercharged |

M | 159 | 20 | Accident (3 hr) | ||

| DNF | 8.0 | 3 | (private entrant) |

Stutz Model M Blackhawk | Stutz 5.3L S8 | D | 159 | 19 | Engine (2 hr) | |

| DNF | 8.0 | 2 | (private entrant) |

Chrysler CG Imperial Eight | Chrysler 6.3L S8 | E | 159 | 18 | Radiator (2 hr) | |

| DNF | 5.0 | 8 | (private entrant) |

Chrysler CD Eight | Chrysler 4.0L S8 | E | 156 | 14 | Radiator (2 hr) | |

| Sources: [30][31][32][33][34] | ||||||||||

- Note *: [B]= car also entered in the 1930-31 Biennial Cup.

- Note **: equivalent class for supercharging, with x1.3 modifier to engine capacity.[35]

- Note ***: #31 was not classified, for failing to complete the final lap of the race in under 30 minutes.

Did Not Start

| Pos | Class | No | Team | Drivers | Chassis | Engine | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNS | 3.0 | 15 | Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 LM | Alfa Romeo 2.3L S8 supercharged |

Engine | ||

| DNA | 3.0** | 18 | (private entrant) |

Bugatti Type 43 | Bugatti 2.3L S8 supercharged |

Did not arrive | |

| DNA | 1.5 | 20 | Ariès CB4 | Ariès 1500cc S4 | Did not arrive | ||

| DNA | 1.5 | 21 | Ariès CB4 | Ariès 1500cc S4 | Did not arrive |

1931 Index of Performance

Class Winners

| Class | Winning Car | Winning Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Over 5-litre | #1 Mercedes-Benz SSK | Ivanowski / Stoffel |

| 3 to 5-litre | #9 Lorraine-Dietrich B3-6 Le Mans | Trébort / Balart |

| 2 to 3-litre | #16 Alfa Romeo 8C-2300 LM | Howe / Birkin * |

| 1500 to 2000cc | no entrants | |

| 1100 to 1500cc | #25 Aston Martin International | Bertelli / Harvey * |

| Up to 1100cc | #29 Caban Spéciale | Vernet / Vallon |

| Note *: setting a new class distance record. | ||

Statistics

- Fastest Lap – B. Ivanowski, #1 Mercedes-Benz SSK– 7:03secs; 139.23 km/h (86.51 mph)

- Winning Distance – 3,017.65 km (1,875.08 mi)

- Winner’s Average Speed – 125.74 km/h (78.13 mph)

References

- Citations

- Spurring 2017, p.54

- Spurring 2017, p.360

- Spurring 2017, p.53

- Clarke 1998, p.90-1: Motor Jun16 1931

- Spurring 2017, p.62-3

- Spurring 2017, p.60-1

- Clausager 1982, p.48-50

- Clarke 1998, p.92-3: Motor Jun16 1931

- Spurring 2017, p.80-1

- Spurring 2017, p.56-7

- Spurring 2017, p.78

- Laban 2001, p.66

- Spurring 2017, p.65-6

- Spurring 2017, p.76-7

- Spurring 2017, p.70-2

- Spurring 2017, p.83

- Spurring 2017, p.68-70

- Spurring 2017, p.72-3

- Spurring 2017, p.82

- Spurring 2017, p.74-6

- Spurring 2017, p.66-7

- Spurring 2017, p.58-9

- Laban 2001, p.70

- Spurring 2017, p.64

- Clarke 1998, p.97-8: Motor Jun16 1931

- Spurring 2017, p.55

- Clarke 1998, p.98-100: Motor Jun16 1931

- Clarke 1998, p.102: Light Car Jun19 1931

- Spurring 2017, p.2

- Spurring 2017, p.84

- "Le Mans 24 Hours 1931 - Racing Sports Cars". www.racingsportscars.com. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "Le Mans History". www.lemans-history.com. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "World Sports Racing Prototypes". www.wsrp.cz. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- "Formula 2". www.formula2.net. Archived from the original on 2017-07-05. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- Spurring 2017, p.18-9

- Bibliography

- Clarke, R.M. - editor (1998) Le Mans 'The Bentley & Alfa Years 1923-1939' Cobham, Surrey: Brooklands Books ISBN 1-85520-465-7

- Clausager, Anders (1982) Le Mans London: Arthur Barker Ltd ISBN 0-213-16846-4

- Laban, Brian (2001) Le Mans 24 Hours London: Virgin Books ISBN 1-85227-971-0

- Spurring, Quentin (2017) Le Mans 1930-39 Sherbourne, Dorset: Evro Publishing ISBN 978-1-91050-513-7

External links

- Racing Sports Cars – Le Mans 24 Hours 1931 entries, results, technical detail. Retrieved 22 Dec 2018

- Le Mans History – entries, results incl. photos, hourly positions. Retrieved 22 Dec 2018

- World Sports Racing Prototypes – results, reserve entries & chassis numbers. Retrieved 22 Dec 2018

- 24h en Piste – results, chassis numbers, driver photos & hourly positions (in French). Retrieved 22 Dec 2018

- Radio Le Mans – Race article and review by Charles Dressing. Retrieved 22 Dec 2018

- Unique Cars & Parts – results & reserve entries. Retrieved 22 Dec 2018

- Formula 2 – Le Mans results & reserve entries. Retrieved 22 Dec 2018

- Motorsport Memorial – motor-racing deaths by year. Retrieved 22 Dec 2018

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 1931 24 Hours of Le Mans. |