Ñ

Ñ (lower case ñ, Spanish: eñe, [ˈeɲe] (![]()

| ISO basic Latin alphabet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unlike many other letters that use diacritic marks (such as Ü in Catalan, Spanish and German and Ç in Catalan, French and Portuguese), Ñ in Spanish, Galician, Basque, Asturian, Leonese, Guarani and Filipino is considered a letter in its own right, has its own name (in Spanish: eñe), and its own place in the alphabet (after N). Historically it came from a doubled N. Its alphabetical independence is similar to the Germanic W, which came from a doubled V.

History

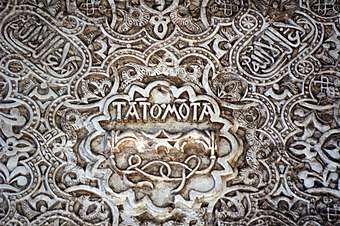

It was engraved in Alhambra after Reconquista by the Catholic Kings, meaning that both Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon were equivalent in power ("Tanto monta, monta tanto, Isabel como Fernando").

Historically, ñ arose as a ligature of nn; the tilde was shorthand for the second n, written over the first;[2] compare umlaut, of analogous origin. This is a letter in the Spanish alphabet that is used for many words, for example, the Spanish word año (anno in Old Spanish) meaning "year" and derived from Latin annus. Other languages used the macron over an n or m to indicate simple doubling.

Already in medieval Latin palaeography, the sign that in Spanish came to be called virgulilla (meaning "little comma") was used over a vowel to indicate a following nasal consonant (n or m) that had been omitted, as in tãtus for tantus or quã for quam. This usage was passed on to other languages using the Latin alphabet although it was subsequently dropped by most. Spanish retained it, however, in some specific cases, particularly to indicate the palatal nasal, the sound that is now spelt as ñ. The word tilde comes from Spanish, derived by metathesis of the word título as tidlo, this originally from Latin TITVLVS "title" or "heading"; compare cabildo with Latin CAPITULUM.[3]

From spellings of anno abbreviated as año, as explained above, the tilde was thenceforth transferred to the n and kept as a useful expedient to indicate the new palatal nasal sound that Spanish had developed in that position: año. The sign was also adopted for the same palatal nasal in all other cases, even when it did not derive from an original nn, as in leña (from Latin ligna) or señor (from Latin SENIOR).

Other Romance languages have different spellings for this sound: Italian and French use gn, a consonant cluster that had evolved from Latin, whereas Occitan, Vietnamese and Portuguese chose nh and Catalan (ny) even though these digraphs had no etymological precedent.

When Morse code was extended to cover languages other than English, the sequence ( — — · — — ) was allotted for this character.

Although ñ is used by other languages whose spellings were influenced by Spanish, it has recently been chosen to represent the identity of the Spanish language, especially as a result of the battle against its obliteration from computer keyboards by an English-led industry.[4]

Cross-linguistic usage

In Spanish and some other languages (such as Philippine languages, Aymara, Quechua, Mapudungún, Guarani, Basque, Chamorro, Leonese and Yavapai), whose orthographies have some basis in that of Spanish, it represents a palatal nasal.

In Galician, it represents such a sound, but it was probably not adopted from Spanish, as evidenced by its presence in the first Galician-Portuguese written in Galicia conserved text (Foro do bo burgo de Castro Caldelas, written in 1228[5][6]). In Tetum, it was adopted to represent the same sound in Portuguese loanwords represented by nh, although this is also used in Tetum, as is ny, influenced by Indonesian.

Other Romance languages also have the sound, written nh in Occitan (espahnòl/espanhòu) and Portuguese (espanhol), gn in Italian (spagnolo) and French (espagnol), and ny in Catalan and Aragonese (espanyol).

The accented letter ń used in Polish, the caroned letter ň (used in Czech and Slovak) and the digraph nj used in Serbo-Croatian are also equivalent to the Spanish letter ñ. The same sound is written ny in Indonesian, Zhuang, and Hungarian, and nh in Vietnamese and Portuguese.

In Tagalog, Visayan, and other Philippine languages, it is also written as ny for most terms. The conventional exceptions (with considerable variations) are proper names, which usually retain ñ and their original Spanish or Hispanicised spelling (Santo Niño, Parañaque, Mañalac, Malacañan). It is collated as the 15th letter of the Filipino alphabet. In old Filipino orthography, the letter was also used, along with g, to represent the velar nasal sound [ŋ] (except at the end of a word, when ng would be used) if appropriate instead of a tilde, which originally spanned a sequence of n and g (as in n͠g), such as pan͠galan ("name"). That is because the old orthography was based on Spanish, and without the tilde, pangalan would have been pronounced with the sequence [ŋɡ] (therefore pang-GAlan). The form ñg became a more common way to represent n͠g until the early 20th century, mainly because it was more readily available in typesets than the tilde spanning both letters.

It is also used to represent the velar nasal in Crimean Tatar, Kiribati, Malay and Nauruan. In Latin-script writing of the distantly-related Tatar language, ñ is sometimes used as a substitute for n with descender, which is not available on many computer systems.

In the Breton language, it nasalises the preceding vowel, as in Jañ /ʒã/, which corresponds to the French name Jean and has the same pronunciation.

It is used in a number of English terms of Spanish origin, such as jalapeño, piña colada, piñata, and El Niño. The Spanish word cañón, however, became naturalized as canyon. Until the middle of the 20th century, adapting it as nn was more common in English, as in the phrase "Battle of Corunna". Now, it is almost always left unmodified. The Society for the Advancement of Spanish Letters in the Anglo Americas (SASLAA) is the preeminent organization focused on promoting the permanent adoption of ñ into the English language.[7]

In the orthography for languages of Senegal, ñ represents the palatal nasal. Senegal is unique among countries of West Africa in using this letter.

The Lule Sami language uses the letter ń, which is often written ñ on computers, since ñ but not ń was available on keyboards and in the Latin-1 character set.

The nj in West Frisian language has a sound somewhat like the Ñ in Spanish

Cultural significance

The letter Ñ has come to represent the identity of the Spanish language. Latino publisher Bill Teck labeled Hispanic culture and its influence on the United States "Generation Ñ" and later started a magazine with that name.[8] Organizations such as the Instituto Cervantes and the National Association of Hispanic Journalists have adopted the letter as their mark for Hispanic heritage.

It was used in the Spanish Republican Air Force for aircraft identification. The circumstances surrounding the crash of serial 'Ñ' Potez 540 plane that was shot down over the Sierra de Gúdar range of the Sistema Ibérico near Valdelinares inspired French writer André Malraux to write the novel L'Espoir (1937), translated into English as Man's Hope and made into the movie named Espoir: Sierra de Teruel.[9]

In 1991, a European Community report recommended the repeal of a regulation preventing the sale in Spain of computer products not supporting "all the characteristics of the Spanish writing system," claiming that it was a protectionist measure against the principles of the free market. This would have allowed the distribution of keyboards without an "Ñ" key. The Real Academia Española stated that the matter was a serious attack against the language. Nobel Prize winner in literature Gabriel García Márquez expressed his disdain over its elimination by saying: "The 'Ñ' is not an archaeological piece of junk, but just the opposite: a cultural leap of a Romance language that left the others behind in expressing with only one letter a sound that other languages continue to express with two."[4]

Among other forms of controversy are those pertaining to the anglicization of Spanish surnames. The replacement of ñ with another letter alters the pronunciation and meaning of a word or name, in the same manner that replacing any letter in a given word with another one would. For example, Peña is a common Spanish surname and a common noun that means "rocky hill"; it is often anglicized as Pena, changing the name to the Spanish word for "pity", often used in terms of sorrow.

When Federico Peña was first running for mayor of Denver in 1983, the Denver Post printed his name without the tilde as "Pena." After he won the election, they began printing his name with the tilde. As Peña's administration had many critics, their objections were sometimes whimsically expressed as "ÑO."

Since 2011, CNN's Spanish-language news channel incorporates a new logo wherein a tilde is placed over two Ns.

Another news channel, TLN en Español, has "tlñ", with an ñ taking the place of the expected n, as its logo.

The city council of A Coruña changed the placement of the tilde from over the ⟨n⟩ to over the initial ⟨c⟩ to create a logo,[10] in a way similar to what was done by the city of Göteborg that changed the dieresis of the ⟨ö⟩ to a colon (⟨Go:teborg⟩). The ⟨ñ⟩ is however not used in the URL.

Computer usage

| Preview | Ñ | ñ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unicode name | LATIN CAPITAL LETTER N WITH TILDE | LATIN SMALL LETTER N WITH TILDE | ||

| Encodings | decimal | hex | decimal | hex |

| Unicode | 209 | U+00D1 | 241 | U+00F1 |

| UTF-8 | 195 145 | C3 91 | 195 177 | C3 B1 |

| Numeric character reference | Ñ | Ñ | ñ | ñ |

| Named character reference | Ñ | ñ | ||

In Unicode Ñ has the code U+00D1 (decimal 209) while ñ has the code U+00F1 (decimal 241). Additionally, they can be generated by typing N or n followed by a combining tilde modifier, ̃, U+0303, decimal 771.

In HTML character entity reference, the codes for Ñ and ñ are Ñ and ñ or Ñ and ñ.

Ñ and ñ have their own key in the Spanish and Latin American keyboard layouts (see the corresponding sections at keyboard layout and Tilde#Role of mechanical typewriters). The following instructions apply only to English-language keyboards.

On Android devices, holding n or N down on the keyboard makes entry of ñ and Ñ possible.

On Apple Macintosh operating systems (including Mac OS X), it can be typed by pressing and holding the Option key and then typing N, followed by typing either N or n.

On the iPhone and iPad, which use the Apple iOS operating system, the ñ is accessed by holding down the "n" key, which opens a menu (on an English-language keyboard). Apple's Mac OS X 10.7 Lion operating system also made the "ñ" available in the same way.

The lowercase ñ can be made in the Microsoft Windows operating system by doing Alt+164 or Alt+0241 on the numeric keypad (with Num Lock turned on);[11] the uppercase Ñ can be made with Alt+165 or Alt+0209. Character Map in Windows identifies the letter as "Latin Small/Capital Letter N With Tilde". A soft (not physical) Spanish-language keyboard is easily installed in Windows.

In Microsoft Word, Ñ can be typed by pressing Control-Shift-Tilde (~) and then an N.

On Linux it can be created by pressing Ctrl+Shift+U and then typing '00d1' or '00f1', followed by space or Ctrl to end the character code input. This produces Ñ or ñ.

Another option (for any operating system) is to configure the system to use the US-International keyboard layout, with which ñ can be produced either by holding Alt Gr and then pressing N, or by typing the tilde (~) followed by n.

Yet another option is to use a compose key (hardware-based or software-emulated). Pressing the compose key, then ~, and then n results in ñ. A capital N can be substituted to produce Ñ, and in most cases the order of ~ and n can be reversed.

Use in URLs

The letter Ñ may be used in internationalized domain names, but it will have to be converted from Unicode to ASCII during the registration process (i.e. from www.piñata.com to www.xn--piata-pta.com).[12]

In URLs (except for the domain name), Ñ may be replaced by %C3%91, and ñ by %C3%B1. This is not needed for newer browsers. The hex digits represent the UTF-8 encoding of the glyphs Ñ and ñ. This feature allows almost any Unicode character to be encoded, and it is considered important to support languages other than English.

See also

Other symbols for the palatal nasal

- Gn (digraph)

- Nh (digraph)

- Nj (letter)

- Ny (digraph)

- Ɲ

- Ń

- Њ

- Ň

- ɲ (IPA symbol)

References

- Repfer to Real Academia Española (RAE - Royal Spanish Academy) http://dle.rae.es/?id=btCZ7EZ

- Buitrago, A., Torijano, J. A.: "Diccionario del origen de las palabras". Espasa Calpe, S. A., Madrid, 1998. (in Spanish)

- Oxford English Dictionary

- "El Triunfo De La Ñ – Afirmación De Hispanoamerica | Blog De Luis Durán Rojo". Blog.pucp.edu.pe. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- "O FORO DO BO BURGO DO CASTRO CALDELAS, DADO POR AFONSO IX EN 1228" (PDF). Consellodacultura.org. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- "Foro Do Bo Burgo Do Castro Caldelas, Dado Por Afonso IX En 1228" (PDF). Agal-gz.org. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- "Eñe Para English". Eñe Para English. Society for the Advancement of Spanish Letters in the Anglo Americas. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Generation-Ñ". Generation-n.com. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- Forging Man's Fate in Spain, The Nation, March 20, 1937

- http://www.coruna.gal/

- Note that this depends on locale. E.g. will generate ń in some eastern European locales, and there is no alternative keystroke for ñ in these locales. The same applies to uppercase Ñ.

- http://mct.verisign-grs.com/convertServlet?input=pi%C3%B1ata

External links