Malappuram district

Malappuram (/mələppurəm/ (![]()

Malappuram district | |

|---|---|

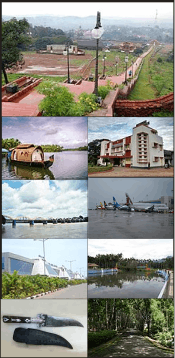

.jpeg)   .png) Clockwise from top: Karipur International Airport, Biyyam lake in Ponnani, A green bypass in Kottakkal, Thooval Theeram beach, Kuttippuram bridge, Karuvarakundu village. | |

| Nickname(s): | |

|

Location in Kerala, India | |

| Coordinates: 11.03°N 76.05°E | |

| Country | |

| State | Kerala |

| District formation | 16 June 1969 |

| Headquarters | Malappuram |

| Subdistricts | |

| Government | |

| • District collector | K.Gopalakrishnan, IAS[5] |

| • District Panchayat President | A. P. Unnikrishnan (IUML)[6] |

| • Members of Lok Sabha | |

| • Members of Niyamasabha | 16 |

| Area | |

| • District | 3,554 km2 (1,372 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 3rd |

| Highest elevation (Mukurthi) | 2,594 m (8,510 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • District | 4,112,920[7] |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 1,157/km2 (3,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 44.18%[8] |

| • Metro | 1,729,522[8] |

| Demography | |

| • Language (2011) | |

| • Religion (2011) |

|

| Human Development | |

| • Sex ratio (2011) | 1098 ♀/1000♂[8] |

| • Literacy (2011) | 93.57%[8] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-KL |

| Vehicle registration |

|

| Website | malappuram |

The district was formed on 16 June 1969 as the tenth district of Kerala by incorporating southern parts of the erstwhile district of Kozhikode and northwestern parts of the erstwhile Palakkad. The eastern part of the district is hilly and the western part is a coastal region. The district is further divided into 5 sub-micro regions. Ponnani, Perinthalmanna, Tirur, Eranad, Tirurangadi, Kondotty, and Nilambur are the seven subdistricts included in the district. The economy of the district basically depends upon emigrants. Malayalam is the most spoken language. Religions practiced in the district include Islam, Hinduism, and Christianity. It is the first e-literate district and the first cyber literate district of India.[12][13] Malappuram metropolitan area is the fourth-largest urban agglomeration of Kerala and the 25th largest of India with a population of 1.7 million.[14]

The district has contributed many writers, and religious and political leaders. During the early medieval period, it was the headquarters of two of the four major kingdoms that ruled Kerala. Perumpadappu was the hometown of the Kingdom of Cochin, which is also known as Perumbadappu Swaroopam, and Nediyiruppu was the hometown of the Zamorin of Calicut, which is also known as Nediyiruppu Swaroopam.

Etymology

The term, Malappuram, which means "over the hill" in Malayalam, is derived from the geography of Malappuram, the administrative headquarters of the district.[15][16]

History

Ancient period

The district has an eventful history since immemorial times. The Stone Age history is not well-revealed. However, the remains of some pre-historic symbols including Dolmens, Menhirs, and Rock-cut caves have been found from various parts of the district, like Nilambur, Manjeri, etc. Rock-cut caves have been found from the places like Puliyakkode, Thrikkulam, Oorakam, Melmuri, Ponmala, Vallikunnu, and Vengara.[17] The port of Ponnani (probably known as Tyndis in ancient period) is believed to be a centre of trade with Ancient Rome and Arabia. During the Sangam period, the region was included in Kudanadu, a province of Ancient Tamilakam. It was ruled by the ancient Chera dynasty.

Early medieval period

After the decline of the ancient Chera Dynasty, several dynasties controlled the area, and by ninth century, the region came under the suzerainty of the Perumals of Mahodayapuram. A piece of inscriptional evidence found at Triprangode indicates that Goda Ravi of Chera Dynasty controlled the present-day district in the early 10th century. Descriptions about the rulers of Eranad region can be seen in Jewish copper plates of Bhaskara Ravi Varman (1000 CE) and Viraraghava copper plates of Veera Raghava Chakravarthy (1225 CE).[17]

After the disintegration of Perumal kingdom, a number of city-states emerged in the region, including Valluvanad, Vettathunadu (Tanur), Parappanad and Nediyiruppu (Eranad) (ruled by the Zamorins).[18][19] Kottakkal, formerly known as Sweta Durgam (the White Fort) in Sanskrit, and Venkalikotta and Venkita Kotta in Malayalam, was a military base of the Kingdom of Valluvanadu in the medieval period.[20] Nediyiruppu was the earlier capital of the Zamorins of Calicut.

During and around the fall of Perumal Empire, the neighbouring Calicut and its environs were ruled over by Porlathiri. The Eradis (A title used to denote the rulers of Eranad) of Nediyiruppu marched with their army to Panniyankara and often surrounded the headquarters of Porlathiri. The ultimate aim was to find access to the sea and thus to participate directly in the maritime trade. This war lasted for almost half a century. The battle ended in the victory of the Eradis. Porlathiri fled to Kolathunadu in search of political asylum.

With the conquest of Polanad, the Eradis who ruled Eranad shifted their headquarters from Nediyiruppu to Calicut, and later began to known as the Zamorin of Calicut. In the early stage of his territorial development, Zamorin expanded his territories to Parappanad and Vettathunad by defeating their rulers.[21][22] The port of Ponnani was a prominent centre of Islamic learning and Tirunavaya was a centre of Vedic learning in medieval Kerala.

Late medieval period

Valluvakonathiri, the ruler of Valluvanad, was the strongest enemy the Zamorin had to face in the earlier stages of his imperial development. The immediate goal of Zamorin was to capture Tirunavaya on the bank of the river Bharathappuzha, which belonged to Valluvakonathiri. Tirunavaya, where the Mamankam festival was celebrated once in every twelve years under the presidency of the king of Valluvanad, was of great political significance. The Zamorin lined up on one side and the Valluvakonathiri along with the ruler of Perumpadappu on other. When the Zamorin's army reached north and settled at Triprangode, Eralpad, the young king of the Zamorin, reached Ponnani by sea, crossed the Bharathappuzha and settled on the other side of Tirunavaya. It was not too long before Valluvakonathiri had to concede defeat. The ruler of Perumpadappu, who fled away to Mahodayapuram, later established the Kingdom of Cochin headquartered at Kochi.

Inspired by the victory at Tirunavaya, the Zamorin continued his attacks. Soon Nilambur, Manjeri, Malappuram, and Venkatakotta (Kottakkal) came under his control. Hence by the end of 13th century, majority of the district came under the control of Nediyiruppu Swaroopam.[21][23][24] However a small portion of the present Perinthalmanna subdistrict remained under the Kingdom of Valluvanad, including Angadipuram, which was the headquarters of the erstwhile Valluvanad.

Thrikkavil Kovilakam in Ponnani served as a second home for Zamorin, and his navy headquarters.[25] Malappuram was the military headquarters of Zamorin.[26] Zamorin earned a greater part of his revenue by taxing the spice trade through his ports. Smaller ports in kingdom included Parappanangadi, Tanur, and Ponnani.[27][28] The headquarters of the Azhvanchery Thamprakkal, who were considered as the supreme religious head of Kerala Brahmins, was at Athavanad.

The works like Kozhikode Granthavari, Mamakam Kilippattu written by Kadanchery Namboodiri in 17th-century CE, Kandaru Menon Patappattu (1683), and Ramchcha Panicker Pattu contains pieces of information about the Mamankam festival held at the bank of Bharathappuzha in Tirunavaya.[29] The modern Malayalam alphabet (accepted by Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan), and the Arabi-Malayalam script (also known as Ponnani script) were developed in the district during the medieval period. The Sanskrit works like Kokila Sandeśa (15th-century CE) written by Uddanda Śāstrī, Bhramara Sandesham (17th century CE) by Vasudevan, and Chathaka Sandesha (18th-century CE) have descriptions about Tirunavaya and Triprangode.[21] Many medieval Malayalam works also help to trace the history of district.

Portuguese attempts of colonisation

Towards the end of the year 1507, the Portuguese Viceroy Francisco de Almeida was informed that a column of 13 Muslim ships had taken cargo - mainly spices - from Ponnani and was about to leave for the Red Sea. The Viceroy immediately decided to corner the fleet. The decision was perhaps made with a view to retrieve the Portuguese prestige lost on account of some incidents at Angediva and Dabul. Almeida himself commandeered the fleet of 12 vessels consisting of four naus, six caravels, and two gales. The fleet had about 6,000 European soldiers, led by a collection of noblemen such as Pero Barreti, Diogo Pires, Lourenco de Almeida, and Nuno da Cunha, son of Tristao da Cunha and a handful of Cochin soldiers.[30]

The defenses of the Ponnani Port were repaired and strengthened by the Zamorin after this event.[25][31] The Zamorin appointed Kunjali Marakkar I, his loyal naval chief, in the port of Ponnani, to resist the Portuguese occupation. It seems that Kunjali Marakkar I, assisted by Kutti Ali and Pacchi Marakkar, subsequently constructed a naval base at Ponnani. Kutti Ali sent harassing raids from Ponnani to Cochin and reinforcement fleets to Kozhikode.[31]

The Zamorin later faced a protest in 1540 by Kutti Pocker, who is popularly known as Kunjali Marakkar II (a title given to the naval chief of the Zamorin) when the Zamorin signed a treaty with the Portuguese power in Ponnani.[32] In 1552, the Zamorin received assistance in heavy guns landed at Ponnani, brought by certain Yoosuf, a Turk, who had sailed against the monsoon winds. In 1566 and again in 1568, Kutti Pocker and his men captured two Portuguese ships. Around a thousand soldiers from one of these ships were killed either by the sword or drowning. Kutti Pocker was later in killed off the coast of Mangalore while returning from a successful raid on the Portuguese fort there.[33]

A Portuguese fleet of 40 vessels under the command of Diogo de Meneses is known to have pillaged Ponnani, sometime before 1570 AD.[31][34] In 1573, Parappanangadi town was burnt by the Portuguese. In 1578, peace negotiations between Zamorin and the Portuguese were strengthened. However, the Zamorin refused to agree to construct a Portuguese fort at Ponnani.[33] It is also known that Gil Eanes Mascarenhas opened fire from his ships to the port and killed a large number of natives in 1582. Mascarenhas was later captured and executed by the forces of Kunjali Marakkar.[35] The Zamorin sent against the Fort Chaliyam certain of his ministers in command over the Muslims of Ponnani, who were assisted by bodies of people from Chaliyam.[25]

The Tuhfat Ul Mujahideen written by Zainuddin Makhdoom II in Ponnani during 16th-century CE is the first-ever book fully based on the history of Kerala, written by a Keralite. It is written in Arabic and contains pieces of information about the resistance put up by the navy of Kunjali Marakkar alongside the Zamorin of Calicut from 1498 to 1583 against Portuguese attempts to colonise Malabar coast.[36] It was first printed and published in Lisbon. A copy of this edition has been preserved in the library of Al-Azhar University, Cairo.[37][38][39]

Colonial period

.png)

When William Keeling, a sea captain of English East India Company arrived at the Kingdom of Calicut in 1615, he was allowed to start warehouses in the port of Ponnani, through a treaty signed with the then Zamorin of Calicut.[40] By the middle of the seventeenth century, the Dutch had attained monopoly over trade in many ports in Kerala. However, some factories in Ponnani came under the trade monopoly of English.[17] During 18th century, the de facto Mysore kingdom rulers Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan marched into Zamorin's kingdom. With headquarters at Manjeri, their army was spread all over the district.[40]

In 1792, Tipu Sultan was defeated by English East India Company through Third Anglo-Mysore War, and the Treaty of Seringapatam was agreed. As per this treaty, most of the Malabar region, including present-day Malappuram district, was integrated into the English East India Company. Hence, the colonial era of the district came into existence. In 1793, the district became a part of the newly formed Malabar Province. Subsequently, the British authority made an arrangement to collect revenue through Zamorin. However, a revolt under the leadership of Manjeri Athan Gurukkal took place against this. It was the first rebellion conducted by Mappilas against the British.[17] The district was administered as parts of Eranad, Valluvanad and Ponnani subdistricts in the South Malabar region during the British rule.

On 20 May 1800, the East India Company separated Malabar from Bombay Presidency and annexed it with the Madras Presidency. The British had established a Barracks called Haig Barracks in the city of Malappuram, which has now been turned into Malappuram Collectorate.[41] The district was the venue for many of the Mappila revolts (uprisings against the British East India Company in Kerala) between 1792 and 1921.

The Malabar district political conference of Indian National Congress held at Manjeri on 28 April 1920, fueled Indian independence movement and national movement in British Malabar.[42] That conference declared that the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms were not able to satisfy the needs of British India. It also argued for a land reform to seek solutions for the problems caused by tenancy that existed in Malabar. However, the decision widened the drift between extremists and moderates within the Congress. The conference resulted in dissatisfaction of landlords with the Indian National Congress. It caused the leadership of the Malabar district Congress Committee to come under the control of the extremists who stood for labourers and the middle class.[21] Malappuram has been part of movements such as Khilafat Movement and Malabar rebellion following the Manjeri conference. The cities/towns of Malappuram, Manjeri, Perinthalmanna, and Tirurangadi were the main strongholds of the rebels. The Wagon tragedy (1921) is still a saddening memory of Malabar rebellion, where 64 prisoners died on 20 November 1921.[43] The prisoners had been taken into custody following the Mappila Rebellion in various parts of the district. Their deaths through apparent negligence generated sympathy for Indian independence movement.

Post-colonial period

Malabar remained as a part of the state of Madras for a few years after the declaration of Indian independence. Later in 1956, Malabar merged with the erstwhile state of Travancore-Cochin following the linguistic reorganisation of states. The newly merged Malabar was divided into Kannur, Kozhikode and Palakkad in 1957. Large-scale changes in the territorial jurisdiction of the region took place between 1957 and 1969. On 1 January 1957, the Tirur subdistrict was formed by adjoining major portions of the Eranad and Ponnani subdistricts. Another portion of the Ponnani subdistrict was carved out to form Chavakkad subdistrict (in Thrissur district), and the remainder is the present-day Ponnani. Perinthalmanna was formed by carving out some portions from the erstwhile Valluvanad subdistrict. Of these, Eranad and Tirur subdistricts remained in Kozhikode district, while Perinthalmanna and Ponnani subdistricts continued in Palakkad. The district of Malappuram was formed with four subdistricts (Eranad, Perinthalmanna, Tirur, and Ponnani), four towns, fourteen developmental blocks, and 100 Gram panchayats. The district was formed in order to vanish backwardness of the region at that time.[44][45] Later, three more subdistricts- Tirurangadi, Nilambur, and Kondotty- were formed from Tirur and Eranad. In the early years of Communist rule in Kerala, Malappuram experienced land reform under Land Reform Ordinance. In the 1970s, Persian Gulf oil reserves were opened to commercial extraction and thousands of unskilled workers migrated to the gulf. They sent money home, supporting rural economy, and by late 20th century the region attained First World health standards and near-universal literacy.[46]

Geography

Bounded by Kozhikode district to the northwest, Wayanad district to the northeast, Nilgiris district to the east, Palakkad district to the southeast, Thrissur district to the southwest, and Arabian Sea to the west, Malappuram has a total geographical area of 3,554 km2, which ranks third in the state in terms of area. The district possesses 9.15% of the total area of the state. The district is located at 75°E - 77°E longitude and 10°N - 12°N latitude on the geographical map. Similar to other parts of Kerala, Malappuram also has a coastal area (lowland) bounded by Arabian Sea on the west, a midland at the centre, and a hilly area (highland), bounded by Western Ghats on the east. Unlike other districts of Kerala, hilly areas are widely seen in the midland area too.

Topography

On the basis of topography, geology, soils, climate, and natural vegetation, the district is divided into 5 sub-micro regions:

- Malappuram coast

- Malappuram undulating plain

- Chaliyar river basin

- Nilambur forested hills

- Perinthalmanna undulating uplands.

Malappuram coast lies all along the coastal tract of Malappuram. It makes its boundaries with Kozhikode coast in the north, Malappuram undulating plain in the east, the Thrissur coast in the south, and the Lakshadweep Sea in the west. The region is drained by the major rivers like Chaliyar, Kadalundi, Tirur, Ponnani, etc. canals and backwaters. The maximum height of this region is located at the Kalpakanchery village (104 m) in the Tirur subdistrict. Malappuram undulating plain lies parallel to the coast. It makes it boundaries with Nadapuram-Mavur undulating plains in the north, Chaliyar river basin and Perinthalmanna undulating uplands in the east, Pattambi undulating plain in the south and Malappuram coast in the west. The Gemini hill (478 m) in Kannamangalam is the highest point and the Vazhayur in the northern part (95 m) is the lowest. Chaliyar river basin entirely lies in the Eranad subdistrict. It makes its boundaries by Nilambur forested hills in its north and east, Perinthalmanna undulating uplands in the south and Malappuram undulating plain in its east. Nilambur forested hills make its boundaries with Kozhikode forested hills and Wayanad forested hills in the north, Tamil Nadu in the east, Mannarkad-Palakkad forested hills in the south and the Chaliyar river basin in the west. It is a part of the Western Ghats. Many peaks with over 1000 m height can be seen here. The lowest point is located in Mampad (115 m). Perinthalmanna undulating uplands make its boundaries with Chaliyar river basin in the north, Mannarkad-Palakkad forested hills in the east, Palakkad Gap in the south and Malappuram undulating plain in the west. The maximum height of the region is 610 metres at the Vadakkangara.[47]

Eranad and Perinthalmanna subdistricts are located in the midland. The vast Nilambur Taluk covers the whole of the jungle area (highland) where the population is less, but the land area (including a lot of forest area) is more.

Coastline

Malappuram ranks fifth in the length of coastlines among districts of Kerala having a coastline of 70 km (11.87% of the total coastline of Kerala).[48] Ponnani, Tanur, Parappanangadi, and Kootayi, which lies in the southwest part of district, are the major fishing centres of district. Ponnani was one of the major ports in history. The sea coast of the district is filled with marine wealth.[47] Apart from being a favourite destination of the Arab traders 2000 years ago, Ponnani was also a captivating destination for many Muslim spiritual leaders, who were instrumental in introducing Islam here. The port city is also known as The Little Mecca of Malabar.[49] During the months of February/April, thousands of migratory birds arrive here. Located close to Ponnani is Biyyam Kayal, a placid, green-fringed waterway with a water sports facility. The Conolly Canal meets with Arabian sea at Puthuponnani. The coastal town of Tanur was the capital of the Kingdom of Vettathunad in the early medieval period, and is known for Keraladeshpuram Temple. Parappanangadi was included in the Parappanad kingdom in the early medieval period.

Rivers

Major rivers flowing through the district are Chaliyar, Kadalundi River, Bharathappuzha, and Tirur River. Chaliyar has a total length of about 168 km. and a drainage area of 2,818 km2 (1,088 sq mi). It passes through Nilambur, Mampad, Edavanna, Areekode, and Vazhakkad in district. Karimpuzha, the largest tributary of Chaliyar, and Thuthapuzha, one of the largest tributaries of Bharathappuzha, also flow through district. Kadalundi River passes through Melattur, Pandikkad, Malappuram, Panakkad, Parappur, Kooriyad, and Tirurangadi. It has a length of 130 km, with a catchment area of 1,114 km2 (430 sq mi) and a total runoff of 2189 million cubic feet. Bharathappuzha has a total length of 209 km. It flows through Thootha, Elamkulam, Pulamanthole, and joins the main river at Pallippuram. Then it again reaches the district at Thiruvegappura after flowing through some neighbouring districts. Tirur River is 48 km long. It joins with Bharathappuzha near to the Ponnani coast. Besides these large rivers, the district also has a small river called Purapparamba River, which is just 8 km long. It is connected to major rivers via Conolly Canal.[47][50]

Climate

The temperature of the district is almost steady throughout the year. It has a tropical climate. It gets significant rainfall in most of the months, with a short dry season. According to Köppen and Geiger, this climate is classified as Am. The average annual temperature in Malappuram is 27.3 °C. In a year, the average rainfall is 2,952 millimetres (116.2 in). Summer usually runs from March until May; the monsoon begins in June and ends in September. Malappuram receives both southwest and northeast monsoons. Winter is from December to February.[51]

| Climate data for Malappuram | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.0 (89.6) |

32.9 (91.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.8 (92.8) |

32.7 (90.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.7 (85.5) |

30.3 (86.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 21.8 (71.2) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.1 (77.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1 (0.0) |

9 (0.4) |

16 (0.6) |

101 (4.0) |

253 (10.0) |

666 (26.2) |

830 (32.7) |

398 (15.7) |

233 (9.2) |

281 (11.1) |

140 (5.5) |

24 (0.9) |

2,952 (116.2) |

| Source: [52] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

The district contains a diverse wildlife and a number of small hills, forests, rivers, and streams flowing to the west, backwaters and paddy, areca nut, cashew nut, pepper, ginger, pulses, coconut, banana, tapioca, and rubber plantations. Conolly's plot, the world's oldest teak plantation, is located at Nilambur in the district. Nilambur is also known for Teak Museum. Bamboo trees are widely seen near to the Nilambur Teak Plantations. A bioresource natural park is associated with the Teak Museum. Tirur Vettila, a type of Betel found in Tirur, has obtained GI tag.[53] Out of the 3,554 km2 area of district, 1,034 km2 (399 sq mi) (29%) constitutes forest area. It may be denser or less dense.[54] The northeast part of district has a vast forest area of 758.87 km2 (293.00 sq mi). In this, 325.33 km2 (125.61 sq mi) is reserved forests and the rest is vested forests. Of these, 80% is deciduous whereas the rest is evergreen. The forest area is mainly concentrated in Nilambur subdistrict, which shares its boundary with the hilly district of Wayanad, Western Ghats, and the hilly areas (Nilgiris) of Tamil Nadu. Trees like teak, rosewood, and mahogany are seen in Nilambur forest area. Bamboo hills are widely seen in the forest. Karimpuzha wildlife sanctuary is the one and only wildlife sanctuary in the district and is also the largest wildlife sanctuary in Kerala.[55][56] The New Amarambalam Reserved Forest, which is a part of Karimpuzha wildlife sanctuary, has a variety of fauna. A variety of animals including elephants, deer, tigers, blue monkeys, bears, boars, rabbits, birds, and reptiles are found in forests. Forest products like honey, medicinal herbs, and spices are also collected from here. Forests are protected by two divisions- Nilambur north and Nilambur south. About 50 Acre of Mangroves forest is found in Vallikkunnu, located in coastal area of the district. A major part of Kadalundi Bird Sanctuary lies in district.[57] The Kadalundi-Vallikkunnu community reserve is the first community reserve in Kerala. It has now been declared as an eco-tourism centre.[58] Tirunavaya is known for its lotus fields.[59]

Administration

Political divisions

Malappuram revenue district has two divisions- Tirur and Perinthalmanna. For sake of rural administration, 94 Gram Panchayats are combined in 15 Block Panchayats, which together form the Malappuram District Panchayat. Besides this in order to perform urban administration better, 12 municipal towns are there.[62]

For the representation of Malappuram in Kerala Legislative Assembly, there are 16 assembly constituencies in district. These are included in 3 Lok Sabha constituencies. Malappuram has the highest number of assembly constituencies in state. Of these, Eranad, Nilambur and Wandoor assembly constituencies together form a part of Wayanad (Lok Sabha constituency), whereas Tirurangadi, Tanur, Tirur, Kottakkal, Thavanur and Ponnani are included in Ponnani (Lok Sabha constituency). The remaining seven assembly constituencies together form Malappuram (Lok Sabha constituency).[62][63] The district is further divided into 138 villages which together form 7 subdistricts.[64]

Subdistricts (Taluks)

Ponnani, Tirur, and Tirurangadi subdistricts lie in the coastal region. Perinthalmanna, Eranad, and Kondotty lie in midland whereas the Nilambur subdistrict shares its boundary with Western Ghats. Nilambur is the largest subdistrict of Kerala in terms of area and Tirur is the largest of Kerala in terms of population.

.svg.png)

| Subdistrict | Area (in km2) |

Population (2011) |

Villages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ponnani | 200 | 379,798 | 11 | |

| Tirur | 448 | 928,672 | 30 | |

| Tirurangadi | 290* | 631,906* | 17 | |

| Kondotty | 254* | 410,577* | 12 | |

| Eranad | 491* | 581,512* | 23 | |

| Perinthalmanna | 506 | 606,396 | 24 | |

| Nilambur | 1,343 | 574,059 | 21 | |

| Sources: 2011 Census of India,[65] Official website of Malappuram district[66] | ||||

State legislature

.svg.png)

| Assembly Constituency |

Political Party |

Political Coalition |

Elected Representative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kondotty | IUML | UDF | T. V. Ibrahim |

| Eranad | IUML | UDF | P. K. Basheer |

| Nilambur | Independent | LDF | P. V. Anvar |

| Wandoor | INC | UDF | A. P. Anil Kumar |

| Manjeri | IUML | UDF | M. Ummer |

| Perinthalmanna | IUML | UDF | Manjalamkuzhi Ali |

| Mankada | IUML | UDF | T. A. Ahmed Kabir |

| Malappuram | IUML | UDF | P. Ubaidulla |

| Vengara | IUML | UDF | K. N. A. Khader |

| Vallikunnu | IUML | UDF | P. Abdul Hameed |

| Tirurangadi | IUML | UDF | P. K. Abdu Rabb |

| Tanur | Independent | LDF | V. Abdurahiman |

| Tirur | IUML | UDF | C. Mammutty |

| Kottakkal | IUML | UDF | K. K. Abid Hussain Thangal |

| Thavanur | Independent | LDF | K.T. Jaleel |

| Ponnani | CPI(M) | LDF | P. Sreeramakrishnan |

Parliament

| Parliamentary Constituency |

Political Party |

Political Coalition |

Elected Representative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wayanad (minor portion) | INC | UDF | Rahul Gandhi |

| Malappuram | IUML | UDF | P. K. Kunhalikutty |

| Ponnani (major portion) | IUML | UDF | E. T. Mohammed Basheer |

Law and Order

The judicial headquarters of the district is in Manjeri. 24 courts function under Manjeri judicial district including Manjeri, Malappuram, Tirur, Perinthalmanna, Parappanangadi, Ponnani, and Nilambur.[67] The headquarters of Malabar Special Police (formed in 1884), a Paramilitary unit under Kerala Police, is located in Malappuram. The Malappuram Police Unit is subdivided into 3 Sub Divisions and 34 Police Stations.

The District Police Office, District Special Branch, District Crime Records Bureau, District 'C' Branch, Narcotic Cell, District Police Control Room, Cyber Cell, Women Cell, and Telecommunication Unit are located in Malappuram. The coastal police station is located in Ponnani whereas the District Armed Reserve Camp is situated in Padinhattummuri. Traffic Units of Malappuram police unit are centered at Malappuram, Manjeri, Kondotty, Perinthalmanna, and Tirur.[68]

Economy

Gross District Value Added (GDVA) of the district in the fiscal year 2018-19 is estimated as ₹ 698.37 billion, and the growth in GDVA, compared to that in the previous year was 11.30%. The district ranks third in the GDVA among the districts of Kerala, followed by Ernakulam and Thiruvananthapuram, as of 2018-19. Net District Value Added (NDVA) of the district in 2018-19 was ₹ 631.90 billion and the annual growth rate of NDVA was 11.59%. Per capita GDVA is estimated to be ₹ 154,463 in the fiscal year. The growth rate of GDVA was 18.12% in 2017–18, 9.49% in 2016–17, 7.86% in 2015–16, 8.83% in 2014–15, 14.08% in 2013–14, and 9.70% in 2012–13. It shows a zigzag trend.[69] The economy of Malappuram largely depends upon emigrants. Malappuram has the highest number of emigrants in state. According to 2016 economic review report published by Government of Kerala, every 54 per 100 households in the district are emigrant households.[70] Most of them work in Middle East. They are major contributors to the district economy. The headquarters of KGB is situated in Malappuram.[71]

Economic minerals

Laterite stone is widely seen in midland areas of the district. Angadipuram Laterite is recognised as a National Geo-heritage Monument.[72] Archean Gneiss is the most seen geological formation of district. Quartz magnetite, which is seen in Porur is one of the economically important minerals found in the district. Quartz gneisses are seen in Nilambur, Edavanna, and Pandikkad. Garneliforus Quartz is seen in Manjeri and Kondotty areas. Charnokite rocks are common in some areas of Nilambur and Edavanna. Dykes consisting of plagioclase, feldspar, and pyroxene in typical laterite texture are there in Manjeri. Deposits of good quality iron ore have reported from Eranad region. Deposits of lime shells are found in coastal areas including Ponnani and Kadalundinagaram. The coastal sands of Ponnani and Veliyankode contain a high amount of heavy minerals like ilmenite and monazite. Kaolinite is seen in Perinthalmanna and Ponnani subdistricts. Deposits of Ball clay have been found from Thekkummuri village. Parts of Nilambur subdistrict are included in the hidden Wayanad goldfields. Explorations done in the valleys of Chaliyar in Nilambur has shown reserves of the order of 2.5 million cubic meters of placers with 0.1 gram per cubic meter of gold.[47] Bauxite was discovered from some parts of the district like Kottakkal, Parappil, Oorakam, and Melmuri.[73]

Industries

Malappuram is one of the industrially backward districts in state due to the lack of infrastructure. There is no industry functioning under Central Sector here. According to the 2011 census, there are 10,629 industrial units registered under SSI/MMSE, and 396 units among these are promoted by Scheduled castes, 83 by Scheduled tribes, and the remaining units by general category. About 1,000 people are aided annually under a self-employment program.

There are KINFRA food-processing and IT industrial estates in Kakkancherry,[74] Inkel SME Park at Panakkad for Small and Medium Industries and a rubber plant and industrial estate in Payyanad. MALCOSPIN (Malappuram Spinning Mills Limited) is one of the oldest industrial establishments in the district under state government. Wood-related industries are common in Kottakkal, Edavanna, Vaniyambalam, Karulai, Nilambur and Mampad. Sawmills, furniture manufacturers and timber trade are the most important businesses in district. Employees' State Insurance has its branch office at Malappuram.[47] KELTRON Electro Ceramics in Kuttippuram, KELTRON tool room in Kuttippuram, Edarikode Textiles in Edarikode, KSRTC body workshop in Edappal, MALCOTEX in Kuttippuram, and KELTEX in Athavanad are the other major industrial centres under public sector.[75] The Kerala State Detergents and Chemicals Ltd. and the Kerala State Wood Industries Ltd. are headquartered at Kuttippuram and Nilambur respectively.[76][77]

Agriculture

Coconut, palms and paddy are mainly found in Malappuram coast. Cashew, coconut, and tapioca are seen in Malappuram undulating plain. Rubber, cashew, pepper, and coconut are the important vegetation found in the Chaliyar river basin. Nilambur forested hills contain the cultivation of a wide variety of species. Teak is mostly seen in this region. Perinthalmanna undulating uplands contain the cultivation of species coconut, palm trees, pepper, rubber, and cashew. The Kadalundi River drains this region. Besides these casual crops, species like mango, jackfruit, banana, etc. are also seen in district.[47]

According to the statistics of 2016–17, the gross cropped area in the district is 237,860 hectares, and the net cropped area is 173,178 hectares. The cropping intensity of the district is 137 hectares. The most produced uncountable crop in 2016-17 was tapioca (185,880 Metric Tonnes), followed by banana (58,564 MT), and rubber (40,000 MT). 878 million coconuts and 19 million jackfruits were produced in 2016–17. However, the land use was maximum for the cultivation of coconut (102,836 hectares), followed by rubber (42,770 hectares), and areca nut (18,379 hectares).[78] An agricultural research station functions at Anakkayam. KCAET at Thavanur is the only agricultural engineering institute in the state.[79]

Transportation

Roads

Malappuram is well connected by roads. There are four KSRTC stations in district.[80] 2 National highways pass through district- NH 66 and NH 966. NH 66 reaches the district through Ramanattukara and connects the cities/towns including Tirurangadi, Kakkad, Kottakkal, Valanchery, Kuttippuram, and Ponnani and goes out from district through Chavakkad. Major cities/towns those are connected through NH 966 include Kondotty (Karipur Airport), Malappuram, and Perinthalmanna. The State Highways passing through district are SH 23, SH 28, SH 34, SH 39, SH 53, Hill Highway, SH 60, SH 62, SH 65, SH 69, SH 70, SH 71, SH 72, and SH 73. The length of road maintained by Kerala PWD in district is 2,680 km. Out of this, 2,305 km constitute district roads. The remaining 375 km consists of State Highways.[81]

Railways

Tirur Railway Station, which was opened in 1861, is the oldest railway station in Kerala. Beypore-Tirur railway line, which was constructed during the colonial period, is the first railway line in the state.[82] Total length of railway line that passes through the district is 142 km.[83] Malappuram City is served by Angadipuram railway station (17 km away), Parappanangadi Railway Station, and Tirur Railway Station both (26 km, 40-minute drive away). A major part of the renowned Nilambur–Shoranur line lies in district. Other railway stations in district are:

- Cherukara railway station

- Kuttippuram railway station

- Melattur railway station

- Nilambur Road railway station

- Pattikkad railway station

- Tanur railway station

- Tirunavaya railway station

- Tuvvur railway station

- Vallikkunnu railway station

- Vaniyambalam railway station

The Ministry of Railways has included the railway line connecting Kozhikode-Malappuram-Angadipuram in its Vision 2020 as a socially desirable railway line. Multiple surveys have been done on the line already. Indian Railway computerized reservation counter is available at Friends Janasevana Kendram, Down Hill. Reservation for any train can be done from here. The Nilambur–Nanjangud line, which connects Nilambur with the Wayanad district, the Nilgiris district, and the Mysore district is under construction.[84]

Airport

Malappuram is served by Karipur International Airport (IATA: CCJ, ICAO: VOCL). The airport started operation in April 1988. It has two terminals, one for domestic flights and second for international flights.[85] Domestic flight services are available to major cities including Bangalore, Chennai, Mumbai, Hyderabad, Goa, Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram, Mangalore and Coimbatore while International flight services connects Malappuram with Dubai, Jeddah, Riyadh, Sharjah, Abu Dhabi, Al Ain, Bahrain, Dammam, Doha, Muscat, Salalah and Kuwait. There are direct buses to the airport for transportation. Other than buses, Taxis, Auto Rickshaws available for transportation.

Demography

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 682,151 | — |

| 1911 | 747,929 | +0.92% |

| 1921 | 764,138 | +0.21% |

| 1931 | 874,504 | +1.36% |

| 1941 | 977,085 | +1.12% |

| 1951 | 1,149,718 | +1.64% |

| 1961 | 1,387,370 | +1.90% |

| 1971 | 1,856,357 | +2.95% |

| 1981 | 2,402,701 | +2.61% |

| 1991 | 3,096,330 | +2.57% |

| 2001 | 3,625,471 | +1.59% |

| 2011 | 4,112,920 | +1.27% |

| source:[86] | ||

In the 2011 census, the district had a population of 4,112,920, which is roughly equal to the population of Croatia. As of census 2011, 12.31% of the total population of Kerala resides in Malappuram. It is the most populous district of Kerala and also the 50th most populous of India's 640 districts, with a population density of 1,157 inhabitants per square kilometre (3,000/sq mi). Its population-growth rate from 2001 to 2011 was 13.39 percent. Malappuram has a sex ratio of 1098 women to 1000 men, and its literacy rate is 93.57 percent, which is almost equal to the average literacy rate of the state (93.91%). Out of the total Malappuram population for 2011 census, 44.18 percent lives in urban regions of district. In 2011, Children under 0-6 formed 13.96 percent of Malappuram District compared to 15.21 percent of 2001. Child Sex Ratio as per census 2011 was 965 compared to 960 of census 2001. According to the census 2011, only 0.02% of the total population of the district is houseless.[8]

The Malappuram metropolitan area has a population of 1.7 million.[14] According to a report published by The Economist in January 2020, Malappuram is the fastest growing metropolitan area of the world.[87][88][89]

Religions

Religion in Malappuram (2011)[10]

The religions practised in district include Islam, Hinduism, Christianity, and other minor religions.[90] Malappuram is one of the two districts in South India, where the Muslims form a majority, the other being Lakshadweep district.

Languages

The principal language used in the district is Malayalam. The Mappila dialect of Malayalam is common in the district. Minority Dravidian languages are Allar (around 350 speakers)[91] and Aranadan, (around 200 speakers).[92] Tamil is also been spoke by a very small fraction of the people. According to the census 2011, the percents of the mother tongue of the total population is as follows:

Health

Modern medicine, Ayurveda, and Homeopathy are available in the district. A general hospital, 3 district hospitals, and 6 Taluk hospitals are functioning under the Government of Kerala for Allopathy. The Government Medical College, Manjeri, established in 2013, is the apex medical college in district.[93] Besides these, a network of local health centers function under the public sector. It includes 66 Primary Health Centres, 20 All-time functioning primary health centers, 20 Community health centers, and 2 TBC's. 5 Major public health centers, 77 mini public health centers, and 565 sub-centers are there. 3 Leprosy control units, 2 Filaria control units, etc. also function under the public sector. The total bed strength of government hospitals is 1500. Many private hospitals with super-specialty units are also there in the district under Allopathy.[94][95]

The Govt Ayurveda Research Institute for Mental Disease at Pottippara near Kottakkal is the only Ayurvedic mental hospital in Kerala. It is also the first of its type under public sector in the country. Kottakkal is also home to the Arya Vaidya Sala, the renowned Ayurvedic health center. Under the government sector, a district Ayurvedic hospital functions in Edarikode. Government Ayurvedic hospitals also function in Manjeri, Velimukku, Perinthalmanna, Malappuram, Vengara, Thozhanur, Thiruvali, and Chelembra. Homeopathic hospitals under public sector function at Malappuram, Manjeri, Wandoor, and Kuttippuram.[95][96] Many hospitals function under the private sector.

Education

The district has the highest number of schools in Kerala as per the school statistics of 2019–20. There are 898 Lower primary schools,[97] 363 Upper primary schools,[98] 355 High schools,[99] 248 Higher secondary schools,[100] and 27 Vocational Higher secondary schools[101] in the district. Hence there are 1620 schools in the district.[102] Besides these, there are 120 CBSE schools and 3 ICSE schools in the district. 554 government schools, 810 Aided schools, and 1 unaided school, recognized by the Government of Kerala have been digitalized.[103] In the academic year 2019–20, the total number of students studying in the schools recognized by Government of Kerala is 739,966 - 407,690 in the aided schools, 245,445 in the government schools, and 86,831 in the recognized unaided schools.[104]

The district also plays a significant role in the higher education sector of Kerala. The district is home to two of the main universities in the state- the University of Calicut centered at Thenhipalam which was established in 1968 as the first university in Malabar region and the second university in Kerala,[105] and the Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University centered at Tirur which was established in the year 2012.[106] AMU Malappuram Campus, one of the three off-campus centres of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) is situated in Cherukara, which was established by the AMU in 2010.[107][108] An off-campus of the English and Foreign Languages University functions at Panakkad.[109]

Culture

Mappila dance forms like Oppana, Kolkali, Duffmuttu, and Aravana muttu are popular in the district. Moyinkutty Vaidyar, the most renowned Mappila paattu poet was born at Kondotty in the district. He is one of the Mahakavis (a title for 'great poet') of Mappila songs. The currently adopted Malayalam alphabet was first accepted by Thunchath Ezhuthachan, who was born in Tirur and is known as the father of modern Malayalam language. Besides Moyinkutty Vaidyar and Thunchath Ezhuthachan, it is also the birthplace of many renowned writers of Malayalam including Edasseri Govindan Nair, K. P. Ramanunni, Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri, Nandanar, Poonthanam Nambudiri, Pulikkottil Hyder, Uroob, and Vallathol Narayana Menon. The district has also given its own deposits to Kathakali, the classical art form of Kerala, and Ayurveda. Kottakkal Chandrasekharan, Kottakkal Sivaraman, and Kottakkal Madhu were famous Kathakali artists hailed from Kottakkal Natya Sangam established by Vaidyaratnam P. S. Warrier in Kottakkal.

During the medieval period, the district was a centre of Vedic as well as Islamic studies. The ancient Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics, though mainly centred in Thrissur, also had scholars coming from Malappuram. The Parameshvara, the Nilakantha Somayaji, the Jyeṣṭhadeva, the Achyutha Pisharadi, and the Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri, who were the main members of the Kerala School of Astronomy and Mathematics hailed from the Tirur region. The Arabi Malayalam script, otherwise known as the Ponnani script, took its birth during the late medieval period. The script was widely used in the district in the late 19th and early 20th century CE.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Malappuram contains a blend of traditional Kerala food items with some of the Arab food items. One of the main elements of this cuisine is Pathiri, a pancake made of rice flour. Variants of Pathiri include Neypathiri (made with ghee), Poricha Pathiri (fried rather than baked), Meen Pathiri (stuffed with fish), and Irachi Pathiri (stuffed with beef). Spices like Black pepper, Cardamom, and Clove are widely used in the cuisine of Malappuram. The main item used in the festivals is the Malabar style of Biryani. Sadhya can also be seen in marriage and festival occasions. Ponnani region of the district has a wide variety of indigenous dishes. Snacks such as Arikadukka, Chattipathiri, Muttamala, Pazham Nirachathu, and Unnakkaya have their own style in Ponnani. Besides these, the other common food items of Kerala can also seen in the cuisine of Malappuram.[110]

Sports

Malappuram is also known as The Mecca of Kerala Football.[1][2] The district has contributed many professional footballers. Malappuram District Sports Complex & Football Academy is situated at Payyanad in Manjeri. Kottappadi Football Stadium is a historical football stadium. Other major stadiums include the Rajiv Gandhi Municipal Stadium at Tirur, and the Perinthalmanna Cricket Stadium at Perinthalmanna. A synthetic track is there along with the Tirur Municipal Stadium. The Malabar Premier League was initiated in 2015 to strengthen the football in Malappuram.[111] The Calicut University Synthetic Track at Thenhipalam is the apex synthetic track of the district. It is associated with the C. H. Mohammed Koya Stadium at Thenhipalam.[112] The other major stadiums of district are at Areekode, Kottakkal, and Ponnani. A football hub to internationalize the eight major football stadiums of district is proposed.[113] The district has also contributed professional sportsmen in the fields of the cricket and the athletics. The construction works of two new stadium complexes are being processed in Tanur and Nilambur.[114]

Places of Interest

According to the statistics of 2017–18, Malappuram ranks sixth in Kerala on the number of foreign tourist arrival and eighth in the number of domestic tourist arrival.[115]

- Adyanpara Falls- is a cascading waterfall in the Kurumbalangode village of Nilambur subdistrict.[116]

- Arimbra Hills, also known as 'Mini-Ooty', since it resembles Ooty. It is at a height of 1050 feet above sea level.[117]

- Arya Vaidya Sala - known for its heritage and expertise in the Indian traditional medicine system of Ayurveda.

- Bharathappuzha - The longest river of Kerala. Also known in the names River Ponnani, Nila and Perar.[118]

- Biyyam Kayal- A backwater lake in Ponnani[119]

- Chekkunnu Mala - A misty green hill near to Chaliyar at Edavanna.[120]

- Cherumb eco-tourist village - A scenic village in the Karuvarakundu[121]

- Kadalundi Bird Sanctuary - a dwelling of more than a hundred species of native birds and over 60 species of migratory birds[122]

- Kadalundi-Vallikkunnu community reserve - The first community reserve in Kerala and an eco-tourism spot. [58]

- Kakkadampoyil - A hilly village on the bank of Cherupuzha.

- Keralamkundu waterfalls - It is located 1500 ft above the sea level in Karuvarakundu.[123]

- Kodikuthimala - At Amminikadan hills, Perinthalmanna. Also known as Mini-Ooty, since it resembles Ooty.[124]

- Kottakkunnu - On the heart of the city of Malappuram. Also known as The Marine Drive of Malappuram. An old fort, a water-park and ancient murals are seen here.[125]

- Nedumkayam Rainforest - A part of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Known for its greenery.[126]

- New Amarambalam Reserved Forest - A wildlife sanctuary near to Nilambur.[127]

- Nilambur Kovilakam - The headquarter of the Nilambur royal family.[128]

- Oorakam Hill - A mount near Malappuram.

- Padinjarekara beach - Two rivers (The Tirur River and the Bharathappuzha) joins with the Arabian sea at here.[129]

- Paloor Kotta Falls - A waterfall adjacent to the Paloor fort built by Tipu Sultan near Perinthalmanna.[130]

- Pandallur hills - A scenic viewpoint near Manjeri. It was determined as the border between Eranad and Valluvanad subdistricts under colonial rule.

- Parappanangadi beach - A beach in the coastal town of Parappanangadi.

- Ponnani beach - A beach in Ponnani.

- Tanur beach - A beach at Tanur.

- Teak Museum - The world's first teak plantation in Nilambur.[131]

- Thunchan Parambu - It is the birthplace of Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan, who is known as the father of modern Malayalam language.

- Vakkad beach - It is at between the Tirur and the Ponnani.[132]

- Vallikunnu beach - A coconut-fringed beach in the northwestern coast of district.[133]

Notable people

- Abdul Nediyodath - an Indian footballer.

- Achyutha Pisharadi - a Sanskrit grammarian, astronomer and mathematician.

- Ahmad Kutty - a North American Islamic scholar

- Anas Edathodika - an Indian professional footballer.

- Aneesh G. Menon - is an Indian actor[134][135]

- Ashique Kuruniyan - an Indian professional footballer.

- Asif Saheer - an Indian soccer player.

- Azad Moopen - an Indian doctor and philanthropist.[136][137][138]

- C. Karunakara Menon - was an Indian journalist and politician.

- C. N. Ahmad Moulavi - was an Indian writer of Malayalam literature.

- Chalilakath Kunahmed Haji - was a social reformer.[139]

- Cherukad - a Malayalam playwright, novelist, poet, and political activist.

- Damodara - was an astronomer-mathematician.

- E. Moidu Moulavi - was an Indian freedom fighter, and an Islamic scholar.[140]

- E. K. Imbichi Bava - was an Indian politician.

- E. M. S. Namboodiripad - The first Chief Minister of Kerala.[141]

- Edasseri Govindan Nair - was an Indian poet.

- Faisal Kutty - a lawyer, academic, writer, public speaker, and human rights activist.[142]

- Gopinath Muthukad - a magician, and motivational speaker.[143][144]

- Govinda Bhattathiri - was an Indian astrologer and astronomer.

- Iqbal Kuttippuram - an Indian screenwriter and homoeopathic physician.[145]

- K. Avukader Kutty Naha - a former deputy chief minister of Kerala.

- K. C. Manavedan Raja - was an Indian aristocrat.

- K. M. Asif - an Indian cricketer.

- K. M. Maulavi - An Indian freedom fighter, social reformer and the founding vice president of IUML.[146][147]

- K. P. Ramanunni - is a novelist and short-story writer.[148][149]

- K. T. Irfan - an Indian athlete.[150][151][152]

- Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma - a resurrector of Mohiniyattam.

- M. G. S. Narayanan - is an Indian historian, and academic and political commentator.

- M. K. Vellodi - former Indian diplomat.

- M. M. Akbar - an Islamic scholar, and an expert in comparative religion.[153]

- M. P. M. Menon - was an Indian diplomat, ambassador to several countries.[154]

- Mankada Ravi Varma - was an Indian cinematographer and director.[155][156][157]

- Mashoor Shereef - an Indian professional footballer.

- Melpathur Narayana Bhattathiri - was a mathematical linguist.

- Mohammed Irshad - an Indian professional footballer.

- Mohamed Salah - an Indian footballer.

- Moyinkutty Vaidyar - was a Mappila pattu poet.[158]

- Nandanar - was an Indian writer of Malayalam literature.

- Nilambur Ayisha - an actress in Malayalam film industry and drama.

- Nirupama Rao - former foreign secretary of India.[159][160]

- P. Surendran - is a writer, columnist, art critic, and a philanthropist.[161]

- Parameshvara - was a major Indian mathematician and astronomer.

- Poonthanam Nambudiri - was a Malayalam poet.[162]

- Pulikkottil Hyder - was a Mappila pattu poet.[163]

- Salman Kalliyath - an Indian professional footballer.

- Sayyid Sanaullah Makti Tangal - was a social reformer.[164][165]

- Shahabaz Aman -[166] an Indian playback singer and composer.[167][168]

- Shanavas K Bavakutty - is an Indian film director.

- Shweta Menon - an Indian model, actress, and television anchor.

- Sithara - an Indian playback singer, composer, and an occasional actor.[169]

- Syed Muhammedali Shihab Thangal - was a religious leader and politician.[170]

- T. M. Nair - was an Indian political activist of Dravidian movement.

- Thunchaththu Ezhuthachan- was a Malayalam poet and linguist.[171][172]

- U.Jimshad - an Indian professional footballer.

- U. Sharaf Ali - a former Indian International football player.[173][174]

- Unni Menon - an Indian playback singer.

- Uroob - was a writer of Malayalam literature.

- V. C. Balakrishna Panicker - an Indian Journalist.

- Vaidyaratnam P. S. Warrier - was an Ayurvedic physician.[175]

- Vallathol Narayana Menon - was a Malayalam poet.[176]

- Variyan Kunnathu Kunjahammed Haji - an Indian Freedom Fighter.[177]

- Vazhenkada Kunchu Nair - was a Kathakali master and a Padma Shri winner.

- Zakariya Mohammed - an Indian Film director, screenwriter and actor.[178][179]

- Zakeer Mundampara - an Indian footballer.

Demand of bifurcation

For a few years, the demand of bifurcating the district into two districts by carving out a new one called Tirur district, centered at Tirur is being strengthened.[180] They argue that it is imperative from the development perspective to split the district, with double the population and size of the Alappuzha district, into two. No other district in Kerala has seven subdistricts, 94 Village Panchayats, and 12 municipalities together. As for its extent, if one travels from Perumbadappu which borders Thrissur district to Vazhikkadavu bordering Tamil Nadu, normally it takes more than three hours to cover that distance of 115 km. They also point out that the problems in the health and educational sectors that require solutions are not trivial. The issue was raised again by the IUML MLA KNA Khader in 2019.[180] The demand is to bifurcate the existing Malappuram district into two districts by carving out a new one called Tirur district from it.[180] KC(M) campaigns for a new district centred at Edappal.[181] Some people including Veteran Congress leader Aryadan Muhammad, and IUML district secretary UA Latheef oppose the bifurcation of Malappuram.[182][183]

However, the demand was rejected by the two successive governments who ruled Kerala in 2013 and in 2019.[182][183] But the studies regarding the bifurcation of the district are still in the consideration of the Government of Kerala.

See also

References

- "Malabar Premier League to be launched in the Mecca of Kerala football". The Hindu. 3 March 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Football hub proposed in Malappuram, the Mecca of Kerala football". Deccan Chronicle. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Kerala kids who sacrificed chocolates to buy football flooded with footballs after video goes viral". m.dailyhunt.in. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Manoj. "Malappuram, the hill top town". nativeplanet.com. Native Planet. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Jaffer Malik,IAS steps down as Malappuram collector; N.Gopalakrishnan,IAS is the new collector". Keralakaumudi dialy. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Malappuram Jilla Panchayath". malappuramdistrictpanchayath.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- "Malappuram-basic information" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Directorate of Census operations, Kerala. pp. 15–16.

- "Census 2011, Malappuram" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Language – Kerala, Districts and Sub-districts". Census of India 2011. Office of the Registrar General.

- "Religion – Kerala, Districts and Sub-districts". Census of India 2011. Office of the Registrar General.

- "Population profile of Kerala". spb.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "The first E-literate district of India". The Times of India. 18 August 2004. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "The first cyber literate district of India". The Hindu. 6 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- "The Malappuram Urban Agglomeration" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Malappuram, The Hill Top Town". nativeplanet.com. 30 June 2014.

- "Cultural counterpoint". The Financial Express. 24 March 2013.

- "History of Malappuram" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Nair, K. K. (2013). By Sweat and Sword: Trade, Diplomacy and War in Kerala Through the Ages. KK Nair. ISBN 978-81-7304-973-6.

- Ramachandran, C. M. Problems of Higher Education in India: A Case Study. Mittal Publications.

- R. Madhvan Nair (6 June 2013). "Medieval swords found at Kottakkal". The Hindu. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Sreedhara Menon, A. (December 2019). A Survey of Kerala History (2019 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 9788126415786.

- Dr. Hari Desai. "The Zamorins of Calicut and Vasco Da Gama". asian-voice.com. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Medieval Kerala" (PDF). education.kerala.gov.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- K. V. Krishna Ayyar, "The Kerala Mamankam" in Kerala Society Papers, Series 6, Trivandrum, 1928-32, pp. 324-30

- K. V. Krishna Iyer Zamorins of Calicut: From the Earliest Times to AD 1806. Calicut: Norman Printing Bureau, 1938

- Logan, William. MALABAR MANUAL: With Commentary by VED from VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS (Volume 2 ed.). VICTORIA INSTITUTIONS, Aaradhana, DEVERKOVIL 673508. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- K. V. Krishna Iyer, Zamorins of Calicut: From the earliest times to AD 1806. Calicut: Norman Printing Bureau, 1938.

- Kunhali. V. "Calicut in History" Publication Division, University of Calicut (Kerala), 2004

- K.P. Padmanabha Menon, History of Kerala, Vol. II, Ernakulam, 1929, Vol. II, (1929)

- K. S. Mathew, Shipbuilding, Navigation and the Portuguese in Pre-modern India Routledge, 2017

- K. K. N. Kurup India's Naval Traditions Northern Book Centre, 1997

- Arrival of Muslims and its impact on Kerala history (PDF). p. 31. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- William Logan. Malabar Manual, Volume 1 Asian Educational Services, 1887

- K. M. Mathew. History of the Portuguese Navigation in India. Mittal Publications, 1988 - Goa, Daman and Diu (India)

- Teotonio R. De Souza. Essays in Goan History Concept Publishing Company, 1989

- AG Noorani "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- A. Sreedhara Menon. Kerala History and its Makers. D C Books (2011)

- A G Noorani. Islam in Kerala. Books

- Roland E. Miller. Mappila Muslim Culture SUNY Press, 2015

- "European treaties of Malappuram" (PDF). shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "History of Malappuram and the Mappila Revolt | Centre for Vedic and Islamic studies". malappuramtourism.org.

- "The 1920 political conference at Manjeri". Deccan Chronicle. 29 June 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Panikkar, K. N., Against Lord and State: Religion and Peasant Uprisings in Malabar 1836-1921

- "The government of Kerala to form Malappuram district". The Hindu. 4 January 1969. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Formation of the Malappuram district" (PDF). shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in.

- "Summer Journey 2011". Time. 21 July 2011.

- "Physical divisions of Malappuram" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. pp. 21–22. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "The coastal area of Malappuram". kerenvis.nic.in. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- "Ponnani, the Mecca of Malabar". nativeplanet.com. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Rivers in Malappuram district". malappuram.nic.in. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "MSN Weather". Archived from the original on 9 October 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- "Climate of Malappuram". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- "Tirur Vettila gets GI tag". The Hindu. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Forest area of Malappuram" (PDF). industry.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "The Karimpuzha Wildlife Sanctuary". The Hindu. 3 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "The largest wildlife sanctuary of Kerala". touristinindia.com. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Flora and fauna of Malappuram". malappuram.nic.in. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "Kadalundi-Vallikkunnu community reserve". www.onmanorama.com. 4 April 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Anupama Mili (4 September 2018). "Lotus fields of Tirunavaya". Malayala Manorama. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "Municipalities in Malappuram". malappuram.nic.in. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "No. of wards in Malappuram". lsgkerala.gov.in.

- "Administrative divisions of Malappuram district". malappuram.nic.in. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Niyamasabha constituencies of Malappuram". ceo.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Talukas in Malappuram district". malappuram.nic.in. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Taluk-wise demography of Malappuram" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala. pp. 161–193. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Villages in Malappuram". malappuram.nic.in. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Judicial administration of Malappuram". districts.ecourts.gov.in.

- "Malappuram police". malappuram.keralapolice.gov.in.

- "Economy of Malappuram". ecostat.kerala.gov.in.

- "Malappuram ranks first in the number of emigrants from Kerala". spb.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "KGB to expand operations in all Panchayats". The New Indian Express. 15 July 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- national geo-heritage of India, INTACH

- "Minerals of Malappuram" (PDF). industry.kerala.gov.in. p. 35. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "KINFRA Techno Industrial Park, Malappuram". kinfra.org.

- "Brief Industrial Profile of Malappuram District 2017-18" (PDF). msmedithrissur.gov.in.

- "Kerala State Detergents and Chemicals Limited". The Economic Times. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- "Kerala State Wood Industries Ltd". The Economic Times. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- "Agriculture in Malappuram". ecostat.kerala.gov.in.

- "Kelappaji College of Agricultural Engineering & Technology, Tavanur | Kerala Agricultural University". kau.in.

- "KSRTC stations of Malappuram". keralartc.com.

- "Length of PWD Roads in Malappuram". kerenvis.nic.in. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- "Beypore-Tirur Railway Line". The Hindu.

- "Railway in Malappuram" (PDF). industry.kerala.gov.in. p. 45. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Nilambur-Nanjandgud way to be realised". The Times of India. 2 September 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Silver jubilee does not bring cheer to Karipur airport users | Kozhikode News - Times of India". The Times of India.

- "Census of India Website : Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India". censusindia.gov.in.

- "Malappuram, the fastest growing city". cnbctv18.com. 9 January 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "Malappuram, the fastest growing city of world". scroll.in.

- "Malappuram is world's fastest-growing city; Kozhikode, Kollam also in top 10". The New Indian Express.

- pp. 396, Malayala Manorama Yearbook 2006, Kottayam, 2006 ISSN 0970-9096

- M. Paul Lewis, ed. (2009). "Allar: A language of India". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (16th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- M. Paul Lewis, ed. (2009). "Aranadan: A language of India". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (16th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "A new government medical college in Kerala after 31 years". The Hindu. 2 September 2013.

- "Healthcare in Malappuram". ecostat.kerala.gov.in.

- "Healthcare in Malappuram". malappuram.nic.in.

- ["Homeopathy in Malappuram". homoeopathy.kerala.gov.in.

- "LP schools in Malappuram". sametham.kite.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "UP schools in Malappuram". sametham.kite.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "High schools in Malappuram". sametham.kite.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "HSE schools in Malappuram". sametham.kite.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "VHSE schools in Malappuram". sametham.kite.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Schools in Malappuram". sametham.kite.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Hi-tech schools in Malappuram". sametham.kite.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "Strength of schools in Malappuram". sametham.kite.kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- "The University of Calicut". uoc.ac.in.

- "Malayalam University". malayalamuniversity.edu.in.

- "Aligarh Muslim University Malappuram Off-centre". amu.ac.in.

- "Universities in Malappuram district". malappuramtourism.org.

- "Eflu to start courses in Malappuram campus on January-31". The Times of India. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Cuisine of Malappuram". malappuramtourism.org. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "Malabar Premier League". The Hindu. 3 March 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Tenhipalam Synthetic Track". Deccan Chronicle. 2 April 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Football hub proposed in Malappuram". Deccan Chronicle. 18 July 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Stadium complexes at Tanur and Nilambur". newsexperts.in. 14 February 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- "Tourism in Malappuram" (PDF). keralatourism.org. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "Adyanpara Waterfalls". keralatourism.org.

- "Arimbra Hills Aka Mini Ooty of Kerala". Art of Legend India. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- "Infobox facts". All Kerala River Protection Council. Retrieved 30 January 2006.

- "The Biyyam backwaters in Ponnani". nativeplanet.com.

- "Chekkunnu Malappuram". Onmanorama. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "Cherumb". tripadvisor.in.

- "Birds of Kadalundi))". keralatourism.org.

- "Keralamkundu waterfalls". keralatourism.org.

- "Kodikuthimala". keralatourism.org.

- "Kottakkunnu". keralatourism.org.

- "Nedumkayam Rainforest". keralatourism.org.

- "BirdLife International (2016) Important Bird and Biodiversity Area factsheet: Amarambalam Wildlife Sanctuary - Nilambur". BirdLife International. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "Nilambur Kovilakam". keralatourism.org.

- "Padinjarekara Beach". keralatourism.org.

- Rajesh R. (18 August 2019). "A trip to Paloor Kotta". Mathrubhumi. english.mathrubhumi.com. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "Teak Museum". keralatourism.org.

- "Vakkad beach". keralatourism.org.

- "Vallikunnu beach". keralatourism.org.

- "Being the usual and unusual actor: Aneesh G Menon". Deccan Chronicle. 19 September 2017.

- "Length of the character matters to me: Aneesh". The Times of India.

- Jagwani, Lohit (12 February 2014). "We are looking at a turnover of $1B by 2017: Azad Moopen, chairman of Aster DM Healthcare". VC Circle. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- Padma Awards Announced Ministry of Home Affairs, 25 January 2011

- "Top 100 Indian Leaders in UAE". Forbes. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- H. Abdul Rahman. Vakkom Moulavi and the Renaissance Movement among the Muslims. Conclusion: University of Kerala-Shodhganga. p. 257. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "Nationalism now linked to mob psychology". The Hindu. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Singh, Kuldip (1 April 1998). "Obituary: E. M. S. Namboodiripad". The Independent. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- "VU law professor among world's most influential Muslims". nwitimes.com. 31 December 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "Indian magician performs Houdini-like escape". Rediff.com. 14 February 1997. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "2011 Yearbook". International Magicians Society. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Article". Samakalika Malayalam Weekly. 19 (48): 47. 22 April 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Muhammed Rafeeq. Development of Islamic movement in Kerala in modern times (PDF). Islahi Movement. p. 115. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Vayalar award for K.P. Ramanunni". The Hindu. 8 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- "manorama online-english". Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- "Irfan qualifies for Olympics in 20 km walk.He completed the walk by touching the finish line at 10th position". dailysports.co. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- "Khushbir fails after Irfan qualifies for Olympics in 20 km walk". The Times of India. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- "Irfan Thodi". The Times of India. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- "Arab News". Arab News.

- "Indian community in UAE mourns death of diplomat", Gulf News, Abu Dhabi, 14 February 2013. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- S Nanda Kumar. "Directpr's Cut". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Painting with light". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 7 September 2007.

- Dore, Shalini (24 November 2010). "Indian cinematographer Varma dies: He worked on Adoor Gopalakrishnan's films". Variety.

- "Mappila songs cultural fountains of a bygone age, says MT". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 31 March 2007. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- Nirupama Rao takes over as Foreign Secy Press Trust of India / New Delhi, Business Standard, 1 August 2009.

- Nirupama Rao is India's new foreign secretary The Times of India, 1 August 2009."Chokila Iyer was first woman, Indian Foreign Secretary in 2001."

- "Award for Short Stories". keralasahityaakademi.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- I K K Menon. FOLK TALES OF KERALA. Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting Government of India. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-81-230-2188-1.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Journal of Kerala Studies Volume 9. (1982): 84.

- Mohammed, U. Educational Empowerment of Kerala Muslims. Calicut (Kerala): Other Books, 2017. 33.

- "Shahabaz Aman: Interview with Shahabaz Aman by Ajith". Shahabazaman4u.blogspot.com. 19 January 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ""Shaam-e-Ehsas" Ghazal Nite by Shahabaz Aman". Hello Bahrain. 29 March 2012. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- "Shahabaz Aman: When I die, I'd rather have people say that Malabar's renowned romantic passed away than just a singer". The Times of India. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Sithara goes to Kollywood". Times of India. 2 March 2012.

- "President, PM, Sonia pay homage to IUML leader Thangal". The Times of India. 2 August 2009.

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds. "Malayalam" Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 2014: (Dallas, Texas) Web. 29 September 2014.

- K. SANTHOSH. "When Malayalam found its feet" THRISSUR, 17 July 2014 The Hindu

- "Minister convenes high-level meet". The Hindu. 4 July 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- "Department of Physical Education". Calicut University. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- mail at aryavaidyasala dot com. "ARYA VAIDYA SALA - Kottakkal". aryavaidyasala.com. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Zarrilli, Phillip (2004). Kathakali Dance-Drama: Where Gods and Demons Come to Play. Routledge. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9780203197660.

- EncyclopaediaDictionaryIslamMuslimWorld Volume 6. 1988. p. 460.

Contemporary evaluation within India tends to the view that the Malabar Rebellion was a war of liberation, and in 1971 the Kerala Government granted the remaining active participants in the revolt the accolade of Ayagi, "freedom fighter"

- "Aravindan Puraskaram awarded to Zakariya Mohammed - Times of India". The Times of India.

- "Sudani from Nigeria wins audience choice award at Russian film festival". The New Indian Express.

- "The demand for bifurcation of Malappuram". thenewsminute.com. 28 August 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "KC(M) to raise new Edappal district". The Times of India. 17 November 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "Pinarayi govt rejects demand for partition of Malappuram". Manoramaonline. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- "No move to bifurcate of Malappuram district: Oommen Chandy". The Economic Times. 26 June 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Malappuram district. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Malappuram District. |

- "dchb malappuram" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in.