Chantilly, Oise

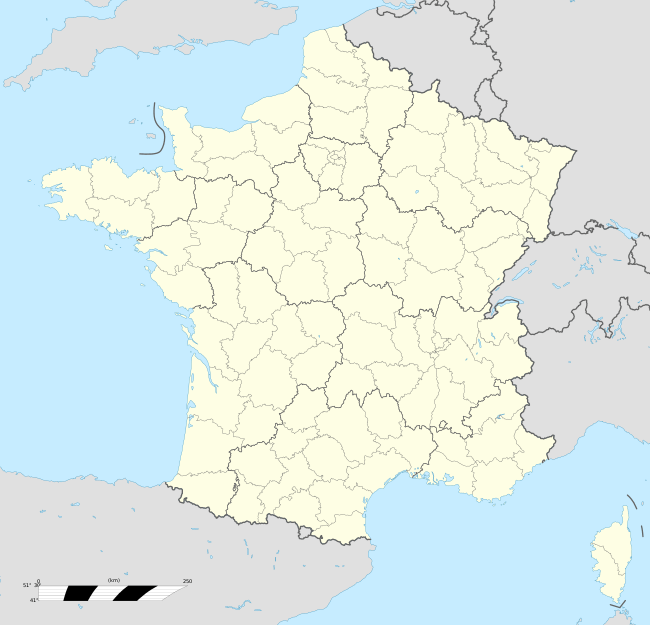

Chantilly (/ʃænˈtɪli/;[2] French pronunciation: [ʃɑ̃.ti.ji]) is a commune in the Oise department in the valley of the Nonette in the Hauts-de-France region of Northern France. Surrounded by Chantilly Forest, the town of 10,863 inhabitants (2017) falls within the metropolitan area of Paris. It lies 38.4 km (23.9 miles) north-northeast of the centre of Paris and together with six neighbouring communes forms an urban area of 36,474 inhabitants (1999 census).

Chantilly | |

|---|---|

Chantilly Town Hall | |

.svg.png) Coat of arms | |

Location of Chantilly

| |

Chantilly  Chantilly | |

| Coordinates: 49°12′00″N 2°28′00″E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Hauts-de-France |

| Department | Oise |

| Arrondissement | Senlis |

| Canton | Chantilly |

| Intercommunality | Aire Cantilienne |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2017–2020) | Isabelle Wojtowiez |

| Area 1 | 16.19 km2 (6.25 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-01-01)[1] | 10,863 |

| • Density | 670/km2 (1,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 60141 /60500 |

| Elevation | 35–112 m (115–367 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Intimately tied to the House of Montmorency in the 15th to 17th centuries, the Château de Chantilly was home to the princes of Condé, cousins of the Kings of France, from the 17th to the 19th centuries. It now houses the Musée Condé. Chantilly is also known for its horse racing track, Chantilly Racecourse, where prestigious races are held for the Prix du Jockey Club and Prix de Diane. Chantilly and the surrounding communities are home to the largest racehorse-training community in France.

Chantilly is also home to the Living Museum of the Horse, with stables built by the Princes of Condé. It is considered one of the more important tourist destinations in the Paris area. Chantilly gave its name to Chantilly cream and to Chantilly lace. The city was the base for the England National Football Team during the Euro 2016 Championship.

Geography

Chantilly lies in the Parisian basin, at the south end of the region of Hauts-de-France and the north end of the Parisian metropolitan area. It belongs to the historic region of Valois. Chantilly lies 39 km southwest of Beauvais, 79 km south of Amiens, and 38 km north of Paris.

Saint-Maximin lies to the north, Vineuil-Saint-Firmin to the northeast, Avilly-Saint-Léonard to the east, Pontarmé and Orry-la-Ville to the south-east, Coye-la-Forêt to the south, Lamorlaye to the southwest, and Gouvieux to the west.

Chantilly is the center of an urban area that includes the communes of Avilly-Saint-Léonard, Boran-sur-Oise, Coye-la-Forêt, Gouvieux, Lamorlaye, and Vineuil-Saint-Firmin. It's the third-largest urban area in the Oise and the seventh-largest in Hauts-de-France. It has no large businesses or heavy industry and 40% of the population works in Ile-de-France, in other words Paris, or its closer suburbs, which are less than an hour away by train.

Topography

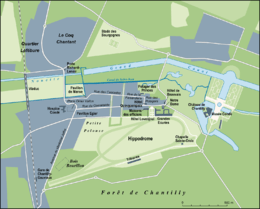

Chantilly straddles the junction of the Paris Basin and the western County of Valois, of which the Nonette river is a boundary. The site of the town was originally a clearing or meadowland, sometimes called a lawn or pelouse, which is mostly occupied today by the racecourse. The remaining open space between the town and the racecourse is always referred to as the "little lawn". The highest point in the area, 112 meters, is at Bois Lorris, in Lamorlaye. The lowest elevation is 35m, at the Canardière on the banks of the Nonette in Gouvieux.

The commune sits on a Lutetian sedimentary limestone plateau covered by Chantilly Forest. Sand created by wind and erosion covers this chalky plateau. Although the sand is less than a meter thick it is very useful for training horses in the forest.

This stone has also been used for building in parts of the region, and still is today in the adjoining commune of Saint-Maximin. It was also used for building in Chantilly itself during the 18th century, when a quarry on the current site of the racecourse produced stone for the court officials' housing and the stables. In the following century the quarry was used to grow mushrooms, then as an air raid shelter during World War II. It now belongs to the Chantilly Estate and is periodically open to the public.[3]

Another geological feature is alluvial accumulations in the river valleys, which have allowed, in the case of the Nonette, the development of community gardens in the locality known as the Canardière.

Hydrology and water supply

The town is bounded at its southern edge by the Thève, a 33 km-long tributary of the Oise River. At this point that valley contains the Commelles ponds, created in the 13th century by the monks of Chaalis Abbey to stock fish.

The Nonette river runs through the town itself. This 44 km-long river is also part of the watershed of the Oise River and is channeled into canals throughout the municipality. In fact, the creation of the château gardens by André Le Nôtre required the complete transformation of the waterway starting in 1663. The riverbed was moved a hundred meters north to create the 2.5 km-long Grand Canal that runs in front of the château. The old riverbed became the 800m-long Canal Saint-Jean, named after a 16th-century chapel demolished when the gardens were created. The Canardière, beneath the actual viaduct, was channeled and cleaned up at this time also.

The Canal de la Machine, perpendicular to the other two and nearly 300 meters long, brought water to the Pavilon du Manse, which fed it to the garden ponds and waterfalls in the western gardens, since disappeared, sending it to a reservoir once located on the lawn. Part of this reservoir still exists near the racecourse, but it no longer contains water. Some of this hydrologic work was used to feed factories in the valley. The gardens that remain were watered by a completely different system based on an aqueduct coming from the area around Senlis.

In the 18th century a mineral water source was discovered in the valley and a garden pavilion was built between 1725 and 1728 to allow the public to come drink from it. This was a separate source from the source of ferruginous water, called Chantilly water, discovered at La Chausée in Gouvieux, and bottled and carbonated there from 1882 into the 20th century.

Also in the 18th century, a supply of drinking water was created by diverting water from the reservoir. In 1823, the last prince of Condé had eighteen fountains installed for the use of residents. In 1895 these were replaced with a supply from a water treatment plant in the neighboring village of Lamorlaye. This brought in water from Chantilly, Lamorlaye and Boran-sur-Oise then distributed the treated water through two water towers on the Mont de Pô in Gouvieux. This water supply has been managed by the private company Lyonnaise des eaux since 1928. In 1999 the average price of a cubic meter of water was 3.25 euros.

The sewer system was installed in 1878 meanwhile, but initially limited to the area around rue d'Aumale, the Condé Hospice and the rue de Paris, now known as the avenue du Maréchal Joffre. It was extended to the entire town in 1910 through a state subsidy financed by a tax on racetrack bets. A sewage treatment plant was built in 1969 at La Canardière, then moved to Gouvieux in 2006. This 22 km network is administered by a regional agency, the syndicat intercommunal pour le traitement des eaux de la vallée de la Nonette (SICTEUV), which covers Apremont, Avilly-Saint-Léonard, Chantilly, Gouvieux et Vineuil-Saint-Firmin.

History

Before the city

No traces of habitation from the prehistoric or Iron Age eras have ever been found in Chantilly. A Roman-era grave site was however found on the banks of the Nonette, and Gallo-Roman roads have been discovered in the Chantilly Forest. Merovingian tombs from the seventh century were found in the 17th and 19th centuries not far from the Faisanderie.[4]

Around 1223 Guy IV of Senlis agreed with the prior of Saint-Leu-d'Esserent that first referred to Terra cantiliaci. He was the royal grand bouteiller, a hereditary position in charge of the king's vineyards, and became the first lord of Chantilly, which at the time was little more than a rock in the middle of a swampy area. A strong house was mentioned in the area in a 1227 document. In 1282 an act of the Parliament of Paris mentions Chantilly Forest.[5] A 1358 document mentions the destruction of the château in the Grande Jacquerie. It was rebuilt by Pierre d'Orgemont and completed in 1394. During the Hundred Years' War Anglo-Burgundian forces laid siege to the château and Jacqueline de Paynel, widow of Pierre II d'Orgemont, who died at the battle of Agincourt, and of Jean de Fayel, was forced to surrender it. In return, the lives of those in the château were spared, but the surrounding villages were laid to waste.[6]

The city began as just a few hamlets scattered outside the château. At the beginning of the 16th century, there were four:

- Les Grandes Fontaines, near the foot of the current rue des Fontaines,

- Les Petites Fontaines, also called Normandie, the foot of the current quai de la Canardière and rue de la Machine,

- Les Aigles, near today's racetrack, which owes its name to the labourers who lived there in the late Middle Ages. It disappeared completely during the French Wars of Religion.

- Quinquempoix, the largest and closest to the château.[7]

In this period, Quinquempoix began to see an extension of the château's functions. It was home to a chapel devoted to Saint Germain mentioned as early as 1219, which disappeared in the 17th century with the extension of the château's gardens. Several houses were built in Quinquempoix to accommodate the prince's court officials. Also, the hôtel de Beauvais, built in 1539, lodged the master of the hunt of constable (connétable) Anne de Montmorency. The hôtel de Quinquempoix, built around 1553, housed the constable's equerry.[8]

In 1515, Anne's father, Guillaume de Montmorency, had obtained a papal bull that gave him the right to have mass said and all the sacraments performed in the chapel of the château, which was one of the first steps toward autonomy from the surrounding parishes.[9]

New parish to modern times

In 1673, Louis II de Bourbon, the Prince of Condé known as the "Grand Condé", built a new road called rue Gouvieux, which is now the rue du Connétable. The land ceded by the château on both sides of this road formed the nucleus of the new town, as guesthouses, workshops for the artisans of the château, and lodgings for servants sprang up. This embryonic town was divided between the parish of Gouvieux in the diocese of Beauvais and the parish of Saint-Léonard in the diocese of Senlis.

Louis expressed a wish in his will for a parish church near the château. Henri Jules de Bourbon-Condé fulfilled his father's wish in 1692 by building the church of Notre-Dame and creating a new parish under the Bishop of Senlis, superseding all existing parishes. Chantilly was thus established as autonomous.

His grandson, Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon, can be called the founder of the city, since he drew up the first city plans. He brought planning to the town design and renamed the rue Gouvieux the Grande Rue. After he built the Great Stables in 1721, he created a development in 1727 and sold lots for housing to court officials, holders of hereditary positions at the court of the Condés. The architectural standards for this housing were drawn by Jean Aubert, architect of the Great Stables. This housing was built between 1730 and 1733. In 1723, the Hospice de la Charité was built at the end of the Grande Rue.

In the second half of the 18th century the princes furthered economic activity. Lace had been produced in the town since the 17th century but now reached its apogee. Porcelain manufacture began in 1726 and was established in the rue de la Machine in 1730. Industrial buildings were built in 1780 at the end of the Grand Canal, to take advantage of the power provided by the waterfall.

The beginnings of the commune

During the French Revolution, Chantilly became a commune whose which boundaries matched those of the parish. The first mayor was the administrator of the estate, André-Joseph Antheaume de Surval. The other city council members were recruited from among the château officials. The Condés were among the first to flee abroad, just days after the fall of the Bastille, on 17 July 1789. The estate was sequestered on 13 June 1792 following the law on émigrés, and subsequently subdivided and sold.[10]

The first section was sold between 1793 and 1795 – the old kitchen garden, the water garden, and the last land available along today's rue du Connétable and around the petite pelouse, as well as the town houses that belonged to the Prince. Much of the land in this first section never came back to the estate. The rest of the land was divided into lots in 1798 and sold over time.[11]

When the Reign of Terror began, the mayor was run out, on 15 August 1793, and replaced by a Jacobin. The château was transformed into a prison from 1793 to 1794, designated for suspects from the département de l'Oise. Sold as a national asset in 1799, the chateau was transformed into a stone quarry by a pair of entrepreneurs. Only the "little château" was preserved. The Great Stables were requisitioned by the army and used in turn by the 11th mounted horse regiment, the 1er dragons or 1st Dragoons from 1803 to 1806 then the 1er régiment de chevau-légers lanciers polonais, or 1st Light Artillery Polish Lancers, from 1808 to 1814.[12]

A number of industrialists took advantage of the sale of Condé assets to further develop their business activities. In 1792, the porcelain manufacturing enterprise turned its hand to ceramics under the hand of its new English owner, Christophe Potter. A copper laminating factory was established in the industrial buildings on the canal in 1801, and François Richard-Lenoir opened a mill in 1807. It employed as many as 600 people and brought prosperity back to the commune. Using the new English techniques, it diversified in cloth, particularly in calico manufacture and laundering. It began to decline in 1814 then lost its monopoly and failed in 1822.

In 1815, prince Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé came back to the area for good. He retrieved part of his family's former estate and bought back the rest. His son, Louis VI Henri, had fountains installed in 1823 as well as many of the street lamps in 1827.

Thomas Muir connection

The Scottish political reformer Thomas Muir had been banished to Botany Bay for 14 years for the crime of sedition in 1793. He managed to escape having only spent 13 months there. An adventurous journey followed that eventually brought Muir as a citizen of France to Paris.

Muir became in time the principal intermediary between the French Directory and the various republican refugees in Paris. He was aware that his movements were under scrutiny by British Prime Minister William Pitt's agents. In his last known communication with the Directory, in October 1798, he requested permission to leave Paris for somewhere less conspicuous, where his crucial negotiations with the Scottish emissaries could be conducted in safety.

Sometime in the middle of November 1798, Muir moved incognito to Chantilly. On 26 January 1799, he died there, suddenly and alone, with only a small child for company. So tight had his security been that not even local officials knew of his presence or identity. No identifying documents or papers were found on his person and his name was discovered only when the postman remembered delivering newspapers to him addressed to 'Citoyen Thomas Muir'. Several days later, when the news of Muir's death reached Paris, a brief obituary notice was inserted in Le Moniteur Universel saying that he had died from a recurrence of his old wounds.

A 19th-century vacation and leisure destination

Chantilly was also in the 19th century a playground for aristocrats and artists, as well as home to an English community with ties to horse racing. The first horse races were run in 1834 on the lawn area known as the pelouse, and the 1840s saw an influx of bettors of all social classes, especially from Paris. The success of the horse races was primarily due to the opening of the train station in 1859. Later, a public station allowed the arrival of up to 20,000 bettors and visitors on race days. A track and permanent seating were gradually added to form the racecourse in use today. Attendance records began to be kept just before World War I; 40,000 people attended the prix du Jockey Club in 1912.[13]

During the Franco-Prussian War, Chantilly was occupied by the Prussian army for almost a year. The Grand Duke of Mecklenburg, head of the 18th Army Corps, occupied the chateau along with his general staff. His troops requisitioned the Great Stables, the racecourse stables, which had been evacuated, and some privately owned residences as well.[14]

A racing economy grew up around the racecourse, with many stables devoted to training thoroughbred horses. Urban development grew up around these racing activities with new neighbourhoods such as the Bois Saint-Denis exclusively devoted to the activity. There were two trainers and seventeen hands in the 1846 and thirty trainers and 309 nands in 1896.[15] Many in the racing community were British—76% of the jockeys, lads and trainers in 1911—and the British were such a presence in the area that an Anglican chapel was built around 1870.[16]

At the same time, Chantilly was becoming a vacation destination with many aristocrats, members of the haute bourgeoisie and artists moving to the area and building villas and chateaux in the surrounding communes, such as the Rothschild family in Gouvieux, for example. Luxury hotels were also built, such as the Hôtel du Grand Condé in 1908.[17] Henri d'Orléans, Duke of Aumale, last lord of the town, encouraged the development of the racecourse and of the town as well as the arrival of the English.

Between 1876 and 1882, the Duke had the château rebuilt and used it to house one of the most beautiful art collections of the time. By receiving high society in his palace, such as Empress Elizabeth of Austria, known as Sissi, and the Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovitch of Russia, he contributed to the growth of the town.[18] When the château was opened to the public in 1898 after it was willed to the Institute of France, it drew even more tourists to the town—more than 100,000 in the first six months.[19]

Naturally such a profusion of wealth also provoked some greed. On the morning of 25 March 1912, the Bonnot Gang robbed the Société Générale de Chantilly and killed two employees before they fled. This was soon before they broke up and Jules Bonnot died in a shootout with police. The groups was notorious for using an automobile to get away and for the coverage provoked by a Jules Bonnot's appearance, brandishing a Browning automatic, at the office of Le Petit Journal to complain about its coverage of their activities.

Chantilly in World War I

The German Army entered Chantilly on 3 September 1914 but did not stay, leaving the next day. The château was occupied but there was no real destruction, unlike the neighboring towns of Creil and Senlis, Oise, where there were fires and considerable destruction. French soldiers did not come back until 9 September. After the First Battle of the Marne, General Joseph Joffre installed his headquarters in Chantilly because of the easy access it offered to Paris by rail. The Grand Quartier-Général, or HQ, took over the hôtel du Grand Condé on 29 November 1914 with 450 officers and 800 clerks and soldiers. Joffre for his part lodged at the Villa Poiret about a hundred yards away.[20][21]

Joffre held the conference of Chantilly from 6 to 8 December 1915 to makes battle plans with his Allied counterparts and to coordinate military offensives for 1916.[22] General Headquarters moved to Beauvais in December 1916, and Chantilly became home to hospitals for soldiers wounded on the front, one in the hôtel Lovenjou, the other in the Egler Pavilion. One of the three camouflage workshops of the French 1st Engineers Regiment opened in 1917 in custom-built barracks on the petite pelouse near the racetrack. Up to 1200 women were hired, as well as 200 German prisoners of war and 200 workers from Annam in French Indo-China (then a French protectorate). They painted canvases which the army used to mask artillery and troop movements from view.[23]

The town grew in 1928 with the annexation of the Bois Saint-Denis from Gouvieux. In 1930 a monument was put up to Maréchal Joffre on the avenue which now bears his name.

World War II

The Wehrmacht entered the city on 13 September 1940, and occupied it. They used the Great Stables as a veterinary hospital for the horses they brought in from Germany, by some estimates the city was home to as many as 400 German horses during the war. The military command took over the hôtel du Grand Condé. Following the assassination of a collaborator, the parish priest, Abbot Charpentier, who authored a 1943 anti-Nazi sermon, was arrested along with several French Resistance fighters he had supported. He was deported to the Mauthausen camp, where he died 7 August 1944.[24] The viaduct at La Canardière was bombed by Allied forces on 30 May 1944, and the town was liberated by American tanks on 31 August 1944. The American 8th Air Force in turn installed itself at the hôtel du Grand Condé.

Post-war Chantilly

Since the war, the city has developed new neighborhoods on the north side of town. Some hotels and villas at the center of town became residences; some stables were torn down to allow housing to be built. As this new housing was built, a new population moved in who mostly work in the Paris area,[25] while the town lost almost all of its remaining industrial base when the Guilleminot factories shut down in 1992.

Monuments and tourist attractions

Château de Chantilly

The château de Chantilly was built for the House of Montmorency, then was home to the Condés and finally to the Duke of Aumale, fifth son of Louis-Philippe. He willed it to the Institute of France. Le château has two parts: the Petit Château and the Château Neuf. The first was built in 1560 by the architect Jean Bullant for the constable Anne de Montmorency. The interior decoration goes back to the 18th century for the larger apartments, and was carried out by Jean Aubert, Jean-Baptiste Huet, and Jean-Baptiste Oudry. The smaller apartments redone in the 19th century are on the ground floor. The Château Neuf was built by architect Honoré Daumet between 1876 and 1882 on the site of the portion of the older building destroyed at the beginning of the 19th century. It contains paint galleries, libraries and the chapel. A gallery, built by architecte Félix Duban in the 1840s, links the two buildings. The château is surrounded by a 115-hectare park which includes 25 hectares of water gardens. The parks includes large formal gardens designed by André Le Nôtre, the Anglo-Chinese garden installed between 1772 and 1774 in the center of which is the Hameau de Chantilly, the English garden installed in 1817 around the temple of Venus on the western side and, near the forest, the La Cabotière and de Sylvie parks. The entire estate was designated a historic monument by the decrees of 24 October and December 1988.

Musée Condé

The Condé Museum in the château has one of the oldest collections of historic art in France and its collection of paintings is only surpassed in France by the Musée du Louvre. The museum also contains a collection of 1,300 manuscripts including the daybook Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. As a condition of its bequest to the Institut de France by the Duke of Aumale, the collection's presentation cannot be modified nor can it be loaned out, so it is a permanent fixture of Chantilly.

The Great Stables

The Grandes Écuries, which contain the Living Museum of the Horse, are among the most-visited horse-racing sites in the world. They were built between 1719 and 1740 by Jean Aubert. They are 186 meters long with a central dome 38 meters high, and could accommodate 240 horses and 500 dogs for the daily rides to hunt. Dressage demonstrations or re-enactments are held daily in the quarry. Horse shows are regularly held beneath the dome.

Porte Saint-Denis

The porte Saint-Denis is part of an unfinished pavilion originally intended to provide symmetry with the current entrance of the Great Stables, on the other side of the open-air stables. When the Duke of Bourbon died in 1740, only this portion remained unfinished when construction stopped. This pavilion was to mark the entrance to the burgeoning city. Its name came from the old land holdings of the Abbey of Saint-Denis, which was once very close to the château.

Urban development

As a city, Chantilly is less than 250 years old. The oldest part is the rue du Connétable, which began in 1727 as a planned allotment called "the officials' housing", allocated from part of the château estate. These buildings are now numbered 25 through 67 on the rue du Connétable. The rest of the neighborhood was sold to the end of the main street, where the Condé hospice stood before the French Revolution.

After 1799, the town spread over the old footprint of the château gardens, with street names recalling the different gardens and sometimes following their old paths. The rue des Potagers, rue de la Faisanderie, and rue des Cascades are examples of this, i.e. Vegetable Street, Pheasantry Street and Waterfall Street. Street numbers here begin from the château rather than from the place Omer Vallon as in other neighborhoods. Development took the form of town houses, small 19th century buildings and other villas surrounded by gardens. Traces also exist of old stables dating from the beginnings of the racehorse community at the start of the 19th century.

Along the avenue du maréchal Joffre development was tied to the Paris road and the arrival of the railway. The station is at the end of the avenue. Here small buildings and villas built in the 19th and 20th century reflect the residential nature the town took on in this period. The area has become progressively more built up as villas and their gardens were replaced with private residences and master houses were transformed into multi-family dwellings.

Chantilly has three outer neighborhoods:

The Bois Saint-Denis[26][27] lies south of town, between the Paris road and the railway. This neighborhood grew out of the construction of stables, which got further and further from the center of town as land became more scarce. Forest parcels belonging to the Duke of Aumale began to be developed in 1890. While this neighborhood was originally within Gouvieux, it became part of Chantilly in 1928. It was then composed of brick stables, trainer residences and lodgings for the lads and jockeys. For a long time it was almost entirely devoted to racing, but over time, beginning in the 1960s, many stables were demolished or transformed into apartment buildings or housing subdivisions. Building codes now specifically protect this heritage and these racing activities.

The Verdun area is at the site of the old train station for the racetrack. (see the article on the Gare de Chantilly – Gouvieux in the French Wikipedia), and lies between the railway and the forest. When the old station closed around 1950, the land was used for apartment buildings, originally limited to railway workers. Much of it still belongs to the SNCF. The city's two high schools are nearby.

North of town neighborhoods lie on terraces overlooking the Nonette. These are made up of public housing (le quartier Lefébure), small subdivisions and privately owned multifamily residences (résidence Sylvie, résidence du Coq Chantant or du Castel) built during the 1960s and 1970s. These neighborhoods have developed their own school and church as well as other amenities used by the city as a whole, such as open space and a stadium.

An intermediate area between the north end of town and the downtown area contains green zones such as the Grand Canal, the Saint-Jean canal and lying between them, in the meadow of the Grand Canal, the community gardens in the area known as La Canardière. The few buildings in this area are tied to Chantilly's old industrial base, such as the François Richard-Lenoir factory and the old Guilleminot factory and its outbuildings.

There are no specific protections for historic buildings or neighborhood preservation, nor is there a historic district such as in Senlis, but the town has local development codes and urban development plans. Much of the land (69%) in Chantilly is forest, so takingthe racecourse into account the city only manages about 25% of its land, much of it around the historic monuments and therefore subject to architectural constraints.[28]

Notable residents

- Pierre d'Orgemont, built the first known chateau.

- François Vatel (1631–1671), maître d'hôtel and believed to be the inventor of Chantilly cream, died in Chantilly

- Henri Jules de Bourbon-Condé (1643–1709), founded the parish of Chantilly.

- Louis IV Henri de Bourbon-Condé (1692–1741), statesman and lord of Chantilly, built the Great Stables.

- Pierre-Joseph Candeille (1744–1827), composer and singer, died at Chantilly.

- Bertrand Bessières (1773–1854), general under Napoleon, lived and died in Chantilly.

- Henriette Méric-Lalande (1798–1867) et Laure Cinti-Damoreau (1801–1863), singers, retired in Chantilly and died there.

- Henri d'Orléans, Duke of Aumale (1822–1897), fifth son of Louis-Philippe I, last lord of Chantilly

- Léopold Delisle (1826–1910), French historian and librarian, retired in the commune and occasionally acted as librarian of the Musée Condé.

- Félix Bollaert (1855–1936), commercial director of the mines at Lens, brother-in-law of mayor Omer Vallon, lived in the rue de Gouvieux and was buried in the cimetière Bourillon.[29]

- Abel Hermant (1862–1950), writer and academic, retired in Chantilly after his imprisonment for collaboration.[29]

- Alfred Heurteaux (1893–1985), soldier and Resistance fighter, died in the commune.

- Princess Nadejda Petrovna of Russia (1898–1988), Russian princess, retired in Chantilly.

- Émilien Amaury (1909–1977), founder of the newspaper Le Parisien, died of a horse-riding accident in the forest and was buried in the cimetière Saint-Pierre.[29]

- Jean Neuberth (1915–1996), painter, died at Chantilly.

- Jean Bruce (1921–1963), author of spy novels, creator of OSS 117, lived in the avenue du Général Leclerc and was buried in the cimetière Saint-Pierre.[29]

Births in Chantilly

- Anne de Montmorency (1492–1567), grand maître of France, then constable

- Louis Antoine de Bourbon-Condé, Duke of Enghien (1772–1804)

- Antoine Guillemet (1841–1918), painter

- Jean de Laborde (1878–1977), French admiral who participated in the scuttling of the French fleet at Toulon

- Alfred Aston (1912–2003), French soccer player

- Jacques Cooper (1931), French stylist

- Daunik Lazro (1945), jazz saxophonist

Economy

The economy of Chantilly has always been intimately associated with the French aristocracy. The most important economic activity, even today, is horse racing, which sprang up in the area due to the nobles who lived nearby. The other major economic center is on tourism.

Slightly more than half of the local population participates in the labor market, and when residents younger than fifteen and older than 64 are excluded the figure rises to 80%. Much of the active workforce, 41%, is employed outside of the Oise,[30] almost all of them in Île-de-France, either in Paris proper or in the area around the Charles de Gaulle Airport. This proportion has been gradually increasing over time. Approximately 7,000 commuters travel into Île-de-France every day.[31]

There are no large employers in Chantilly or its immediate environs. The largest is the Lycee Jean Rostand, followed by the city itself and the information technology company EDI. None has more than 250 employees.[31] On 1 January 2007, the city had 801 business, 193 of them retail.[32] The unemployment rate at the most recent census was 8.4% vs 10.7% for the Oise as a whole. For labor market purposes Chantilly is considered part of the Sud-Oise, which, along with Amiens, is the largest labor pool in Picardy.[33]

Horse Racing

Chantilly is the largest center of horse training activities in France, with 2,633 horses, 2,620 of them thoroughbreds, lodged in approximately a hundred training stables. This represents 70% of the race horses in Paris. The next closest, at Maisons-Laffitte, only has about 800. About two thousand area residents are directly or indirectly employed in this field.

Given the real estate crunch inside city limits, nowadays stables can only be found in the Bois St-Denis neighborhood, where there are thirty, which specialise in gallop. Fifty-four others, also specializing in gallop, can be found in Lamorlaye, Gouvieux, Coye-la-Forêt and to a lesser extent at Avilly-Saint-Léonard. Fifty-nine jockeys live in Chantilly and 109 in the rest of the municipal area.[34]

Some of the more famous trainers in the area are Criquette Head-Maarek, Freddy Head, Pascal Bary, André Fabre, Marcel Rolland, Elie Lellouche, Nicolas Clément, Alain de Royer-Dupré and those attached to the stables of Karim Aga Khan IV. Noted jockeys in the area include Dominique Bœuf, Christophe-Patrice Lemaire, Olivier Peslier, Thierry Thuilliez and Thierry Jarnet.

France Galop

The stables affiliated with France Galop use a number of installations that the organization manages and maintains. Sixty permanent and thirty seasonal employees work at these installations, which encompass 1900 hectares. Among these installations is the des Aigles track at Gouvieux as well as others at Lamorlaye and Coye-la-Forêt, which has thirty-odd trainers working in a 60-hectare facility, as well as the 15-hectare track at Avilly-Saint-Léonard. France Galop also manages 47 kilometers of trails covering 1500 hectares in Chantilly Forest, which are strictly limited to horses at certain times of day.[35]

In all, the organization manages 120 hectares of grass, 120 kilometers of sand trail and one dirt trail used 365 days a year regardless of the weather, which translates to 33,000 gallops a year including 2000 at the racecourse alone.[36]

Equine Businesses

A number of professionals and businesses specializing in racehorses have grown up in the Chantilly area. Two prominent horse transportation companies are based in Lamorlaye and Gouvieux respectively.[37] Three veterinarians within the municipal boundaries specialize in horses, and another five in the adjacent communes.[38] Chantilly has one farrier and there are another four nearby. Similarly, there is one saddler and another seven based outside town.[39] Chantilly has two racehorse dealers; another five are based in the surrounding area.[40]

A horse-racing school, AFASEC's "The Windmill" is based in Gouvieux and provides instruction to 185 jockeys and trainees, many of whom are housed in a facility in Chantilly proper.[41] Finally, there are plans to build a biomass plant that will use the manure generated by the stables.[42]

Racecourse

The racecourse hosts 25 meets and 197 races every year, including the prestigious Prix du Jockey Club and Prix de Diane. It is one of six Parisian racecourses managed by France Galop, although it is owned by the Institut de France.

When it was threatened with closing, 24 million euros were raised to modernize it by a public interest group that included the mayor's office, France Galop, the Institute of France, the CCAC, an intergovernmental commission of Chantilly-area governments, the Oise council, the Picary regional council, and Prince Karim Aga Khan. Work was completed in 2007 and included a new ring, repairs and modernization of the stands, a scale and a new parking area. It now receives 40,000 visitors a year.[43]

Tourism

Tourism in Chantilly centers on the Domaine de Chantilly, which owns the chateau and associated lands. The chateau itself had roughly a quarter million visitors in 2007, while the Living Museum of the Horse drew 149,000.[44] The other big tourist draw is Chantilly Forest, which received as many as four million visits yearly. This makes it the 7th most-visited forest in the Paris region.[45] Most of the visitors are day excursionists. Unlike Versailles and Fontainebleau, foreign tourists account for only 15% of the traffic, which can at peak times reach 20,000 simultaneous visitors to the various Domaine properties.[46] Every year an international show jumping competition, the Chantilly Jumping, which is part of the Global Champions Tour, is held in 2 arenas in the middle of the racecourse.[47]

At the heart of the Parc naturel régional Oise-Pays de France, Chantilly is surrounded by history. The medieval city of Senlis and its cathedral are only ten kilometers away and the abbeys of Chaalis, Moncel, and Royaumont are only slightly further, as is the priory at Saint-Leu-d'Esserent. Natural attractions also abound, such as the forests of Halatte and Ermenonville, and Parc Jean-Jacques-Rousseau in Ermenonville. Nearby theme parks like La Mer de sable and Parc Astérix also draw visitors to the area.

In 2005, due to difficulties the Institute of France was experiencing with the management of the domain, the more important elements of the domain were taken over by a non-profit corporation created and supported financially by the Aga Khan, charged with economic development, restoration and the development of tourism.[48][49]

Business tourism is another important factor. Proximity to Paris and to the Charles de Gaulle airport combine with the high quality of local hotel properties make it a prime conference destination. More than two thousand are held there every year. Chantilly and its immediate vicinity have three four-star hotels:

- the Dolce in Vineuil-Saint-Firmin

- the Montvillargenne in Gouvieux

- the Mont-Royal a little further away at La Chapelle-en-Serval

There are also four three-star hotels. A conference center run by the Capgemini corporation is also located in the immediate vicinity, in Gouvieux.[50] Another four-star hotel is being built in the Rue du Connétable near the Jeu de Paume, with an additional luxury residence planned for Avilly-Saint-Léonard.[51]

Chantilly Arts and Elegance Richard Mille

The automobile elegance contest of Chantilly Arts & Elegance Richard Mille takes place in the castle. It is one of the most prestigious elegance competitions in the world, such as the Concorso d'Eleganza Villa d'Este in Italy, Pebble Beach Concours d'Elegance in California and Amelia Island Concours d'Elegance in Florida.

Communication and transportation

Roads

The old king's road that once connected Pierrefitte-sur-Seine to Dunkirk by way of Amiens bisects Chantilly from north to south. Formerly known as route nationale 16 this road has been renamed departmental road 1016. Trucks are not illegal on this road, but signs to the north and south of town suggest taking the A1 or A16 instead. The D924a connects to the Flanders road, the old route nationale 17, at La Chapelle-en-Serval. The D924 runs to Senlis. Trucks are banned on both of these roads, which connect to the A1. The speed limit on D924a is 70 km/h for its entire length through the commune, since it passes through Chantilly Forest, which has many deer crossings.

Rail and public transportation

The Chantilly-Gouvieux train station was put into service in 1859 on the Paris–Lille railway. It is served by the SNCF via the TER Hauts-de-France network. Express trains reach Paris-Nord in 22 minutes and Creil in seven.[52]

The station is also served by line D of the Île-de-France RER. In 2006, 920,000 trips took place between Chantilly and Paris-Nord.

A small public bus network, Desserte urbaine cantilienne (DUC), links the Lefébure neighborhood to Bois-St-Denis by way of the train station. A branch goes past the château and the Saint-Pierre cemetery. Passengers ride for free.

Airports and airport access

Chantilly is roughly 30 km from Charles de Gaulle Airport and 54 km from the Beauvais-Tillé Airport. There is no direct route to either by public transportation.

An airfield named aérodrome de la Vidamée-Chantilly was opened in 1910 in Courteuil and served as a military air base during World War I.[53] It has since disappeared. Another airfield, known as terrain de Chantilly-Les Aigles, was created during World War II by requisitioning the Les Aigles horse training center in Gouvieux. It was occupied during the Battle of France by the chase group I/1 from the Étampes-Mondésir air base.[54]

Trails

.jpg)

Two hiking trails cross the commune. The GR 11 circles the greater Paris area and runs between Senlis and Saint Maximin. It cuts through the parc de Sylvie on the château grounds, goes through the Porte Saint-Denis and descends to the Saint-Jean canal, running alongside it until it cuts across the neighborhood known as Coq chantant (Crowing Rooster). The GR 12, which runs from Paris to Amsterdam, goes from Senlis through the south end of town towards the Commelles ponds, then reaches Coye-la-Forêt. The GR 1, known as Tour de Paris, runs along the southeastern edge of town on the south bank of the Commelles ponds.

Chantilly Forest is criss-crossed with many paths, which are barred to pedestrians between 6 am and 1 pm, to allow horses to be trained. Chantilly finished a network of bike paths in June 2008 which allow access by bike to Gouvieux, Vineuil-Saint-Firmin et Avilly-Saint-Léonard.

Sights

- The surrounding Chantilly Forest

- The Château de Chantilly

- The Chantilly Racecourse

- The Musée Condé

International relations

Chantilly is twinned with:

.svg.png)

Climate

The climate in the Val d'Oise is comparable to that of northern Ile-de-France, and has been described as falling somewhere between the oceanic climate of Brest on the coast and the continental climate of Strasbourg. Rainfall is relatively light and with moderately heavy rainfall in spring and early summer, then again in the autumn, which is typical of oceanic climates, but storms are of the continental variety.[55]

| Climate data for Chantilly, Oise, France | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9 (48) |

10.2 (50.4) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.1 (57.4) |

20.9 (69.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.2 (50.4) |

4.8 (40.6) |

15.2 (59.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

1.2 (34.2) |

3.7 (38.7) |

4.6 (40.3) |

10 (50) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13 (55) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.6 (47.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

6.7 (44.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 53 (2.1) |

38 (1.5) |

91 (3.6) |

53 (2.1) |

64 (2.5) |

24 (0.9) |

34 (1.3) |

71 (2.8) |

29 (1.1) |

76 (3.0) |

47 (1.9) |

31 (1.2) |

611 (24) |

| Source: Météo France, Creil weather station, 2008 | |||||||||||||

See also

References

- "Populations légales 2017". INSEE. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Chantilly". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Édouard Launet (12 September 2007), "Le trou d'où sort Paris", Libération, retrieved 22 July 2009

- Carte archéologique de la Gaule: 60. Oise, éditions de la MSH – Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, 1995, pp. 202–203, ISBN 2-87754-039-1

- Gérad Mahieux (2008), Les origines du château et de la seigneurie de Chantilly, 1, Cahiers de Chantilly

- Macon 1908 p. 10–16

- Macon 1908 p. 30–31

- Macon 10–12 and 23–25

- Macon 1909–1910, pp 15 and 57

- Macon 1908, pp 16–19 and 24–26

- Macon 1909–1910 p. 97–114

- Macon 1912, p. 26–35, 44, 62 and 67

- Blay 2006, p. 273, chapter entitled Une culture urbaine sous influence parisienne et anglaise

- Chantilly sous la botte (1870–1871), Association de sauvegarde de Chantilly et de son environnement, 1990

- Blay 2006, p. 138, chapter entitled Évolution des structures et spécialisation des emplois

- Jean-Pierre Blay (1992), Industrie hippique, immigration anglaise et structures sociales à Chantilly au xixe siècle, 8–2, Revue européenne de migrations internationales, pp. 121–132

- Blay 2006, p. 179–207, chapter entitled Loisirs mondains, vie sportive et snobisme de classe à la Belle époque

- Blay 2006, p. 63–77, chapter entitled Le duc d'Aumale et Chantilly : bienveillance princière et pérennité du domaine

- Chronologie de Chantilly, association de sauvegarde de Chantilly et de son environnement, January 2007, archived from the original on 23 February 2011, retrieved 20 July 2009

- Au sujet de Chantilly pendant la Première Guerre mondiale: Chantilly en 1914–1918, photographies inédites de Georges et Marcel Vicaire (PDF), Ville de Chantilly-Château de Chantilly, 2008, ISBN 978-2-9532603-0-4, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2011

- Bernard Chambon (2008), Le Grand quartier général à Chantilly (1914–1917), 1, Cahiers de Chantilly, pp. 59–103

- François Cochet (2006), 6–8 décembre 1915, Chantilly : la Grande Guerre change de rythme, 242, Revue historique des armées

- Département d'histoire locale du centre culturel Marguerite Dembreville de Chantilly (2008), Les p'tites camoufleuses de Chantilly, Notice sur l'atelier de camouflage de l'armée française en 1917–18 à Chantilly (Oise) (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2013, retrieved 9 January 2013

- L'abbé Charpentier 1882–1944, l'association de sauvegarde de Chantilly et de son environnement, January 2007, archived from the original on 5 September 2009, retrieved 20 July 2009

- L'Oise et ses cantons – Chantilly (PDF), Insee, 2006, retrieved 20 July 2009

- Michel Bouchet (2004), "Le Quartier du Bois Saint-Denis d'hier à aujourd'hui", Études cantiliennes, Association pour la sauvegarde de Chantilly et de son environnement, p. 23

- Jean-Pierre Blay (2006), "Le bois Saint-Denis, une quartier conquis par Chantilly pour le cheval (1891–1930)", Les Princes et les jockeys, 1, Atlantica, pp. 90–105, ISBN 2-84394-903-3

- chambre régionale des comptes de Picardie (16 September 2003), Rapport d'observations définitives sur la gestion de la commune de Chantilly (PDF), Cour des Comptes – site des Juridictions financières, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2011

- Muriel Le Guen, Guide pour la visite des cimetières cantiliens, mairie de Chantilly

- Dossier statistique sur la commune de Chantilly [archive] sur site de l'Insee, juin 2009. Consulté le 22 juillet 2009

- L'Oise et ses cantons – Chantilly [archive] sur site de l'Insee, 2006. Consulté le 20 juillet 2009

- Dossier statistique sur la commune de Chantilly sur site de l'Insee, juin 2009. Consulté le 22 juillet 2009

- Carte des zones d'emploi et nombre d'emplois au 31 décembre 2006 sur www.eco.picardie.net. Consulté le 22 juillet 2009

- Entraîneurs et jockeys adhérents à l'Association général des jockeys de galop en France recensés dans le Guide pratique édité par l'Association des entraîneurs de Galop, édition 2008

- Le centre d'entraînement de Chantilly sur site du journal France Galop. Consulté le 22 juillet 2009

- Guide pratique, Association des entraîneurs de galop, 2008, p. 251–252. Chiffres 2006

- STH Hippavia sur www.sth-hipavia.com. Consulté le 7 août 2009, la plus ancienne originaire de Chantilly et STC Horse de Gouvieux

- Liste des adhérents à l'association sur site de l'association vétérinaire équine française. Consulté le 22 juillet 2009

- Pages jaunes (Yellow Pages)

- Coming to France? (liste des membres) sur site de l'association française des courtiers en chevaux de galop (AFC). Consulté le 22 juillet 2009

- L'école " Le Moulin à Vent " Chantilly-Gouvieux [archive] sur site de l'école des courses hippiques. Consulté le 22 juillet 2009

- Marie Persidat, " L'usine de méthanisation revient au Mont-de-Pô ", Le Parisien, 3 juillet 2009 [texte intégral [archive] (page consultée le 28 juillet 2009)]

- Vivre à Chantilly, L'hippodrome de Chantilly, no 90, p. 4–5, juillet-août 2009

- Touriscopie 2007 : les chiffres du tourisme dans l'Oise, 2007, retrieved 22 July 2009

- La fréquentation des forêts publiques en Île-de-France, CREDOC, July 2000

- Sabine Gignoux (13 May 2009), "Karim Aga Khan, chef spirituel des ismaéliens (1/2) : "À Chantilly, comme ailleurs, la culture est créatrice de ressources"", La Croix, p. 23

- "Homepage | Jumping Chantilly". jumping-chantilly.com. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- La Fondation pour la sauvegarde et le développement du domaine de Chantilly, Institut de France

- Grégoire Allix,Emmanuel de Roux (26 March 2005), "L'Aga Khan remet en selle le domaine de Chantilly", Le Monde, retrieved 1 July 2009

- Page d'accueil, Les Fontaines

- Avilly-Saint-Léonard : le complexe hôtelier prévu pour la fin 2011, Le Parisien édition Oise, 26 February 2009

- Horaires des trains Paris-Chantilly-Creil (PDF), SNCF, 2012, retrieved 8 January 2012

- Patrick Serou, L'Aérodrome de la "Vidamée", retrieved 20 July 2009

- Frédéric Gondron (1999), "Un aérodrome peu connu, " Les Aigles " Gouvieux/Chantilly (août 1939-juin 1940)", Bulletin de la société historique de Gouvieux (Oise) no 10

- The data below is for 2008. "France: Climate", Encyclopædia Britannica

Bibliography

- Gustave Macon, Histoire des édifices de culte de Chantilly, in Comité archéologique de Senlis, Comptes-rendus et mémoires, années 1900–01, Senlis, Imprimerie de Charles Duriez, 4th edition vol. IV, 1902, p. 179–260 (ISSN 1162-8820)

- Gustave Macon, Histoire de Chantilly, in Comptes-rendus et Mémoires, années 1908 à 1912, Comité archéologique de Senlis, Senlis (original edition) / Res Universis, Amiens (second edition), 1909–1913 (reprinted 1989), reproduction of the original edition originale, four volumes in one (ISBN 2-87760-170-6) (ISSN 1162-8820).

- unequaled summary of the city's history from its origins to the 19th century

- Jean-Pierre Babelon and Georges Fressy, Chantilly, Scala, 1999, 247 p. (ISBN 2-86656-203-8).

- Focuses on the château

- Jean-Pierre Blay, Les Princes et les jockeys, Biarritz, Atlantica, 2006, 630 p. (ISBN 2-84394-903-3).

- Thesis on Chantilly history in the 19th and early 20th century, focuses on relationship with horse racing

- La Ville du cheval souverain, volume 1

- Vie sportive et sociabilité urbaine, volume 2

- Thesis on Chantilly history in the 19th and early 20th century, focuses on relationship with horse racing

- Isabelle Dumont-Fillon, Chantilly, Alan Sutton, Mémoire en images collection, 1999 (ISBN 2-84253-301-1)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chantilly. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Chantilly. |

- Chantilly's portal (in French)

- Museum of the Horse

- Businesses in Chantilly)