West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (Ukrainian: Західноукраїнська Народна Республіка, Zakhidnoukrayins’ka Narodna Respublika, ZUNR) was a short-lived republic that existed from November 1918 to July 1919 in eastern Galicia. It included the cities of Lviv, Przemyśl, Ternopil, Kolomyia, Boryslav and Stanislaviv (now Ivano-Frankivsk), and claimed parts of Bukovina and Carpathian Ruthenia. Politically, the Ukrainian National Democratic Party (the precursor of the interwar Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance) dominated the legislative assembly, guided by varying degrees of Greek Catholic, liberal and socialist ideology.[1] Other parties represented included the Ukrainian Radical Party and the Christian Social Party.

West Ukrainian People's Republic Західноукраїнська Народна Республіка Zakhidnoukrayins’ka Narodna Respublika | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918–1919 | |||||||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||

Anthem: Ще не вмерла Україна (Ukrainian) Shche ne vmerla Ukraina (transliteration) Ukraine has not perished | |||||||||||||||

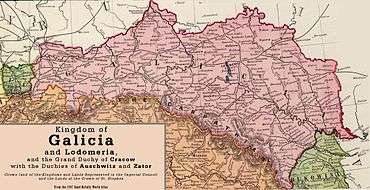

Map of the areas claimed by the West Ukrainian National Republic | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Partially recognized state | ||||||||||||||

| Location | Central Europe | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Lviv (to Nov 21, 1918) Ternopil (to end of 1918) Stanislaviv (Ivano-Frankivsk) Zalishchyky (early June 1919) | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Ukrainian, Polish, Rusyn, Yiddish | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||

• 1918 | Kost Levytsky | ||||||||||||||

• 1919 | Yevhen Petrushevych | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Ukrainian National Council | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | World War I | ||||||||||||||

• Established | November 1, 1918 | ||||||||||||||

| January 22, 1919 | |||||||||||||||

• Polish-Ukrainian War | July 1919 | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1910 | 5,400,000 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Ukraine |

|

|

Early history

|

|

Modern history

|

|

Topics by history |

|

|

The coat of arms of the West Ukrainian People's Republic was azure, a lion rampant or (a golden lion rampant on a field of blue). The colours of the flag were blue and yellow.

History

Background

According to the Austro-Hungarian census of 1910, the territory claimed by the West Ukrainian People's Republic had about 5.4 million people. Of these, 3,291,000 (approximately 60%) were Ukrainians, 1,351,000 (approximately 25%) were Poles, 660,000 (approximately 12%) were Jews, and the rest included Rusyns, Germans, Hungarians, Romanians, Czechs, Slovaks, Romani, Armenians and others. The cities and towns of this largely rural region were mostly populated by Poles and Jews, while the Ukrainians dominated the countryside. This would prove problematic for the Ukrainians, because the largest city, Lviv (Polish: Lwów, German: Lemberg), had a majority Polish population and was considered to be one of the most important Polish cities.

The oil reserves near Lviv at Drohobych and Boryslav in the upper Dniester River were among the largest in Europe. Rail connections to Russian-ruled Ukraine or Romania were few: Brody on a line from Lviv to the upper Styr River,[lower-alpha 1] Pidvolochysk (Podwoloczyska) on a line from Ternopil to Proskurov (now Khmelnytskyi) in Podolia, and a line along the Prut from Kolomyia (Kolomca) to Chernivtsi (Czernowitz) in Bukovina.

Thus the stage was set for conflict between the West Ukrainian People's Republic and Poland.

Independence and struggle for existence

The West Ukrainian People's Republic was proclaimed on November 1, 1918.[2] The Ukrainian National Rada (a council consisting of all Ukrainian representatives from both houses of the Austrian parliament and from the provincial diets in Galicia and Bukovina) had planned to declare the West Ukrainian People's Republic on November 3, 1918 but moved the date forward to November 1 due to reports that the Polish Liquidation Committee was to transfer from Kraków to Lviv.[3] Shortly after the republic proclaimed independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire a popular uprising took place in Lviv, where most residents were Polish and did not want to be part of a non-Polish state. A few weeks later Lviv's rebellious Poles received support from Poland. On November 9 Polish forces attempted to seize the Drohobych oil fields by surprise but were driven back, outnumbered by the Ukrainians.[4] The resulting stalemate saw the Poles retaining control over Lviv and a narrow strip of land around a railway linking the city to Poland, while the rest of eastern Galicia remained under the control of the West Ukrainian National Republic.

Meanwhile, two smaller states immediately west of the West Ukrainian People's Republic, also declared independence as result of the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[5]

- The Komancza Republic was an association of thirty Lemko villages, based around Komańcza in eastern Lemkivshchyna. It existed between November 4, 1918 and January 23, 1919. Being pro-Ukrainian it planned to unite with the West Ukrainian People's Republic, but was suppressed by the Polish government as part of the Polish–Ukrainian War.

- On December 5, 1918 the Ruska Narodna Respublika Lemkiv (Lemko Rusyn National Republic) also declared independence. The Lemko Rusyn National Republic was centered on Florynka, a village in the south-east of present-day Poland. Russophile sentiment prevailed among its inhabitants, who were opposed to a union with the West Ukrainian People's Republic and instead sought unification with Russia.

An agreement to unite western Ukraine with the rest of Ukraine was made as early as December 1, 1918. The government of the West Ukrainian People's Republic officially united with the Ukrainian People's Republic on January 22, 1919.[2] This was mostly a symbolic act, however.

Since western Ukraine had a different tradition in its legal, social and political norms it was to be autonomous within a united Ukraine.[6] Furthermore, western Ukrainians retained their own Ukrainian Galician Army and government structure.[7] Despite the formal union, the Western Ukrainian Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic fought in separate wars. The former was preoccupied with a conflict with Poland while the latter struggled with Soviet and Russian forces.[6]

Relations between the West Ukrainian People's Republic (ZUNR) and the Kiev-based Ukrainian People's Republic were somewhat strained. The leadership of the former tended to be more conservative in orientation.[8] Well-versed in the culture of the Austrian parliamentary system and an orderly approach to government, they looked upon the socialist revolutionary attitude of their Kiev-based peers with some dismay and with the concern that the social unrest in the East would spread to Galicia.[9] Likewise, the West Ukrainian troops were more disciplined while those of Kiev's Ukrainian People's Army were more chaotic and prone to committing pogroms,[10] something actively opposed by the western Ukrainians.[11] The poor discipline in Kiev's army and the insubordination of its officers shocked the Galician delegates sent to Kiev.[9]

The national movement in western Ukrainian was as strong as in other eastern European countries,[12] and the Ukrainian government was able to mobilize over 100,000 men, 40,000 of whom were battle-ready.[13]>Ludwik Mroczka writes that despite the strength of the Ukrainian nationalist forces, they received little support and enthusiasm from the local Ukrainian population, in general the attitude was often that of indifference, and male Ukrainian population often tried to avoid the service in its military[14] During the Polish-Ukrainian War, the army of the West Ukrainian People's Republic was able to hold off Poland for approximately nine months[6] but by July 1919, Polish forces had taken over most of the territory claimed by the West Ukrainian People's Republic.

Exile and diplomacy

Part of the defeated army found refuge in Czechoslovakia and became known there under the name Ukrajinská brigáda (Czech), while most of the army, consisting of about 50,000 soldiers, crossed into the territory of the Ukrainian People's Republic and continued the struggle for Ukrainian independence there.

In July 1919, the West Ukrainian People's Republic established a government-in-exile in the city of Kamianets-Podilskyi.[15] Relations between the exiled Western Ukrainian government and the Kiev-based government continued to deteriorate, in part because the Western Ukrainians saw the Poles as the main enemy (with the Russians a potential ally) while Symon Petliura in Kiev considered the Poles a potential ally against his Russian enemies. In response to the Kiev government's diplomatic talks with Poland, the Western Ukrainian government sent a delegation to the Soviet 12th Army, but ultimately rejected Soviet conditions for an alliance. In August 1919, Kost Levytsky, head of the Western Ukrainian state secretariat, proposed an alliance with Anton Denikin's White Russians which would involve guaranteed autonomy within a Russian state. Western Ukrainian diplomats in Paris sought contact with Russian counterparts in that city.[16] The Russian Whites had mixed views of this proposed alliance. On the one hand, they were wary of the Galicians' Russophobia and concerned about the effect of such an alliance on their relationship with Poland. On the other hand, the Russians respected the discipline and training of the Galician soldiers and understood that an agreement with the Western Ukrainians would deprive Kiev's Ukrainian People's Army, at war with the Russian Whites, of its best soldiers.[8] In November 1919 the Ukrainian Galician Army, without authorization from their government, signed a ceasefire with the White Russians and placed their army under White Russian authority. In talks with Kiev's Directorate government, Western Ukrainian president Petrushevych argued that the Whites would be defeated anyway but that the alliance with them would strengthen relations with the Western powers, who supported the Whites, and would help the Ukrainian military forces for their later struggle against the victorious Soviets. Such arguments were condemned by Petliura. As a result, Petrushevych recognized that the West Ukrainian government could no longer work with Petliura's Directorate and on November 15 the government of the West Ukrainian People's Republic left for exile in Vienna.[16]

Treaty of Warsaw (1920)

In April 1920, Józef Piłsudski and Symon Petliura agreed in the Treaty of Warsaw to a border on the river Zbruch, officially recognizing Polish control over the disputed territory of Eastern Galicia. In exchange for agreeing to a border along the Zbruch River, recognizing the recent Polish territorial gains in western Ukraine, as well as the western portions of Volhynian Governorate, Kholm Governorate, and other territories (Article II), Poland recognized the Ukrainian People's Republic as an independent state (Article I) with borders as defined by Articles II and III and under otaman Petliura's leadership.[17]

Neither the Polish government in Warsaw nor the exiled Western Ukrainian government agreed to this treaty.

Autonomous status

Western Ukrainians continued pressing their interests during the negotiations following World War I at the Paris Peace Conference. These efforts ultimately resulted in the League of Nations declaring on February 23, 1921 that Galicia lay outside the territory of Poland, that Poland did not have the mandate to establish administrative control in that country, and that Poland was merely the occupying military power of Eastern Galicia, whose fate would be determined by the Council of Ambassadors at the League of Nations.

After a long series of further negotiations, on March 14, 1923 it was decided that eastern Galicia would be incorporated into Poland "taking into consideration that Poland has recognized that in regard to the eastern part of Galicia ethnographic conditions fully deserve its autonomous status."[18] The government of the West Ukrainian People's Republic then disbanded, while the Polish government reneged on its promise of autonomy for eastern Galicia.

Government

From November 22 to November 25 elections took place in Ukrainian-controlled territory for the 150-member Ukrainian National Council that was to serve as the legislative body. Yevhen Petrushevych, the chairman of the Council and a former member of the Austro-Hungarian parliament, automatically became the Republic's president. Subordinated to him was the State Secretariat, whose members included Kost Levytsky (president of the secretariat and the Republic's minister of finance), Dmytro Vitovsky (head of the armed forces), Lonhyn Tsehelsky (secretary of internal affairs), and Oleksander Barvinsky (secretary of education and religious affairs), among others.[19] The country essentially had a two-party political system, dominated by the Ukrainian National Democrats and by its smaller rival, the Ukrainian Radical Party. The ruling National Democrats gave some of their seats to minor parties in order to ensure that the government represented a broad national coalition.[20] In terms of the Ukrainian National Council's social background, 57.1% of its members came from priestly families, 23.8% from peasant households, 4.8% from urban backgrounds, and 2.4% from the petty nobility.[21] In terms of the identified council members' vocational background, approximately 30% were lawyers, 22% were teachers, 14% were farmers, 13% were priests, and 5% were civil servants. Approximately 28% had Ph.D.'s, mostly in law.[22]

The West Ukrainian People's Republic governed an area with a population of approximately 4 million people for much of its nine-month existence. Lviv functioned as the Republic's capital from November 1 until the loss of that city to Polish forces on November 21, followed by Ternopil until late December 1918 and then by Stanislaviv (present-day Ivano-Frankivsk) until May 26, 1919.[20] Despite the war, the West Ukrainian People's Republic maintained the stability of the pre-war Austrian administration intact, employing Ukrainian and Polish professionals. The boundaries of counties and communities remained the same as they had been during the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The county, regional, and local courts continued to function as they had while the country had been a part of Austria, as did schools, the postal service, telegraphs and railroads.[20] Austrian laws remained temporarily in force. Likewise, the government generally retained the Austrian system of tax collection, although war losses had impoverished the population and the amount of taxes collected was minimal. Most of the government's revenue came from the export of oil and salt.

Although ethnic Poles represented only a small minority in the rural areas, prior to World War I almost 39% of eastern Galician lands had been in the hands of large Polish landowners.[16] The Western Ukrainian People's Republic passed laws that confiscated vast manorial estates from private landlords and distributed this land to landless peasants. Other than in those limited cases, the right to private property was made fundamental and expropriation of lands was forbidden. This differentiated the policies of the West Ukrainian People's Republic from those of the socialistic Kiev-based Ukrainian government.[20]

The territory of the West Ukrainian People's Republic comprised 12 military districts, whose commanders were responsible for conscripting soldiers. The government was able to mobilize 100,000 soldiers in the spring of 1919, but due to a lack of military supplies only 40,000 were battle-ready.

In general, the government of the West Ukrainian People's Republic was orderly and well-organized. This contrasted with the chaotic state of the Ukrainian governments that arose on the territory of the former Russian Empire.

Policies towards national minorities and inter-ethnic relations

Historian Yaroslav Hrytsak stated that the Ukrainian nationalism that developed before the First World War in Austria was anti-Polish, but neither "very xenophobic" nor antisemitic.[23] In November 1918 a decision was made to include cabinet-level state secretaries of Polish, Jewish and German affairs.[6] According to Hrytsak during the entire time of its existence there were no cases of mass repressions against national minorities in territories held by the West Ukrainian People's Republic, Hrytsak states that this differentiated the Ukrainian government from that of Poland.[20] Katarzyna Hibel writes that while officially West Ukrainian People's Republic like Poland declared guarantees of rights of its national minorities, in reality both countries were violating them and treated other foreign nationalities like fifth column.[24] On February 15, 1919 a law was passed that made Ukrainian the state language. According to this law, however, members of national minorities had the right to communicate with the government in their own languages.

Treatment of Polish population

Historian Rafał Galuba writes that Polish population was treated as second class citizens by West Ukrainian authorities [25] After 1 November several members of Polish associations were arrested or interned by Ukrainian authorities; similar fate awaited officials who refused to swear an oath of loyalty to Ukrainian state.[26] On 6 November a ban on Polish press and publications was issued in Lviv by Ukrainian authorities and printing presses demolished [27] (Poles had similarly banned Ukrainian publications in territories they controlled [28]) Ukrainian authorities tried to intimidate Polish population in Lviv by sending soldiers and armed trucks into the streets and dispersed crowds that could turn to Polish demonstrations.[29] Christoph Mick states that initially, the Ukrainian government refused to take Polish hostages[30] but as both the Polish civilian and military resistance to Ukrainian forces grew, Polish civilians were threatened with summary executions by Ukrainian commander in chief for alleged attacks and shots on Ukrainian soldiers. In response, the Polish side proposed a peaceful solution of the conflict and joint Polish-Ukrainian militia to oversee the public safety in the city.[30]

In Zloczow 17 Poles were executed by Ukrainian authorities[31] In Brzuchowice Polish railwaymen who refused to comply with Ukrainian orders to work were executed[32]

On 29 May 1919 archbishop Jozef Bilczewski sent a message to Ignacy Paderewski attending Peace Conference in Paris, asking for help in facing brutal murders of Polish priests and civilians by Ukrainians.[33]

Poles didn't support the Ukrainian authorities and set up an underground resistance movement that engaged in acts of sabotage.[28] All fieldwork was stopped, the harvest destroyed and machinery purposely broken; Poles also issued to keep up the morale among the population. In response Ukrainian authorities engaged in terror, including mass executions, court martial and set up detention centers where some Poles were interned.[34] The conditions in these camps involved unheated wooden barracks, lack of bedding and lack of medical care, resulting in high levels of morbidity from typhoid. Estimated casualties at these camps include nearly 900 at a camp in Kosiv, according to various sources from 300 to 600 (dying from typhoid) in Mikulińce, 100 in Kołomyja, and 16 to 40 in Brzeżany, due to unheated barracks at temperatures of -20 degrees Celsius. Cases of robbing, beating, torturing or shooting of Polish prisoners were reported.[35]

According to Christopher Mick the Ukrainian government in general treated the Polish population under its control no worse than the Polish government treated the Ukrainians under its control.,[28] writing that Ukrainian authorities didn't treat Polish population "gently" and that Ukrainian authorities mirrored Polish authorities by making speaking in Polish unwelcome.[36] Mick acknowledges that Ukrainian side during the siege of Lviv stopped caring about supplies reaching the city and attempted to disrupt water supply to city. It's fierce artillery fire killed many civilians, including women and children.[28]

Treatment of Jewish minority

Although relations between Poles and the West Ukrainian People's Republic were antagonistic, those between the Republic and its Jewish citizens was generally neutral or positive. Deep-seated rivalries existed between the Jewish and Polish communities, and anti-Semitism, particularly supported by the Polish National Democratic Party, became a feature of Polish national ideology. As a result, many Jews came to consider Polish independence as the least desirable option following the First World War. In contrast to the antagonistic position taken by Polish authorities towards Jews, the Ukrainian government actively supported Jewish cultural and political autonomy as a way of promoting its own legitimacy. The Western Ukrainian government guaranteed Jewish cultural and national autonomy, provided Jewish communities with self-governing status, and promoted the formation of Jewish national councils which, with the approval of the Western Ukrainian government, established the Central Jewish National Council in December 1918 to represent Jewish interests in relation to the Ukrainian government and to the Western allies.[37] The Council of Ministers of the West Ukrainian National Republic bought Yiddish-language textbooks and visual aids for Jewish schools and provided assistance to Jewish victims of the Polish pogrom in Lviv. The Ukrainian press maintained a friendly attitude towards the West Ukrainian Republic's Jewish citizens. Their Hebrew and Yiddish schools, cultural institutions and publishers were allowed to function without interference.[37] Reflecting the republic's demographics, approximately one-third of the seats in the national parliament were reserved for the national minorities (Poles, Jews, Slovaks and others). The Poles boycotted the elections, while the Jews, despite declaring their neutrality in the Polish-Ukrainian conflict, participated and were represented by approximately 10 percent of the delegates. Localized anti-Jewish assaults and robberies by Ukrainian peasants and soldiers, while far fewer in number and less brutal than similar actions by Poles, occurred between January and April 1919. The government publicly condemned such actions and intervened in defence of the Jewish community, imprisoning and even executing perpetrators of such crimes.[37] The government also respected Jewish declared neutrality during the Polish-Ukrainian conflict. By the orders of Yevhen Petrushevych it was forbidden to mobilize Jews against their will or to otherwise force them to contribute to the Ukrainian military effort.[11] In an effort to aid Western Ukraine's economy, the Western Ukrainian government granted concessions to Jewish merchants.[37]

The West Ukrainian government's friendly attitude towards Jews was reciprocated by many members of the Jewish community. Although Jewish political organizations officially declared their neutrality in the Polish-Ukrainian struggle, many individual Jews offered their support or sympathized with the West Ukrainian government in its conflict with Poland. Jewish officers of the defunct Austro-Hungarian army joined the West Ukrainian military, and Jewish judges, lawyers, doctors and railroad employees joined the West Ukrainian civil service.[38] From November 1918, ethnic Poles in the civil service who refused to pledge loyalty to the West Ukrainian government either quit en masse or were fired; their positions were filled by large numbers of Jews who were willing to support the Ukrainian state. Jews served as judges and legal consultants in the courts in Ternopil, Stanislaviv, and Kolomyia.[37] Jews were also able to create their own police units,[39] and in some locations the Ukrainian government gave local Jewish militias responsibility for the maintenance of security and order. In the regions of Sambir and Radekhiv approximately a third of the police force was Jewish.[37] Jews fielded their own battalion in the army of the Western Ukrainian National Republic,[40] and Jewish youths worked as scouts for the West Ukrainian military.[37] Most of the Jews cooperating with and serving in the West Ukrainian military were Zionists.[22] In general, Jews made up the largest group of non-ethnic Ukrainians who participated in all branches of the West Ukrainian government.[37]

The liberal attitude taken towards Jews by the Western Ukrainian government could be attributed to the Habsburg tradition of inter-ethnic tolerance and cooperation leaving its mark on the intelligentsia and military officers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[37]

Postage stamps

The republic issued about one hundred types of postage stamps during its brief existence, all but two of which were overprints of existing stamps of Austria, Austria-Hungary or Bosnia.[41]

Gallery

Rail lines of Galicia before 1897

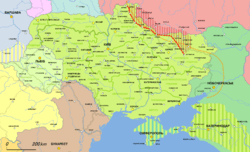

Rail lines of Galicia before 1897 Territorial claims of Ukraine in 1918

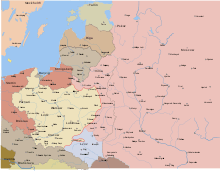

Territorial claims of Ukraine in 1918 The West Ukrainian People's Republic in 1919

The West Ukrainian People's Republic in 1919

See also

- Ukrainian Galician Army or UHA, the military forces of the West Ukrainian National Republic.

- Galician Soviet Socialist Republic, revolutionary government installed by Soviet Russia in 1920.

Notes

- The Styr River valley had seen significant fighting between Russia and the Central Powers during the First World War.

References

- John Armstrong (1963). Ukrainian Nationalism. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 18-19.

- Russia And Ukraine by Myroslav Shkandrij, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-7735-2234-4 (page 206)

- Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 5, 1993 entry written by Andrzej Chojnowski

- Alison Fleig Frank. (2005). Oil empire: visions of prosperity in Austrian Galicia. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 207-228

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (Fall 1993). "The Ukrainian question between Poland and Czechoslovakia: The Lemko Rusyn republic (1918-1920) and political thought in western Rus'-Ukraine". Nationalities Papers. 21 (2): 95–103. doi:10.1080/00905999308408278.

- Michael Palij. (1995). The Ukrainian-Polish defensive alliance, 1919–1921: an aspect of the Ukrainian revolution. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press at University of Alberta, pp. 48-58

- Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. pp. 362. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- Anna Procyk. (1995). Russian nationalism and Ukraine: the nationality policy of the volunteer army during the Civil War. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press at the University of Alberta, pp. 134-144.

- Peter J. Potichnyj. (1992). Ukraine and Russia in their historical encounter. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, University of Alberta pg. 148: Dr. Lonhyn Tsehelsky, the western Ukrainian negotiator with the Kiev government and primary author of the Union between the West Ukrainian Republic and the Kiev-based Ukrainian People's Republic, expressed shock at the actions of the "rabble" (holota) when the Ukrainian People's Republic came to power.

- Andrew Wilson (1997). Ukrainian nationalism in the 1990s: a minority faith. Cambridge University Press pg. 13

- Myroslav Shkandrij (2009). Jews in Ukrainian literature: representation and identity. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 94-95

- Subtelny, Orest. (1988). Ukraine: a History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pg. 378

- Subtelny, Orest. (1988). Ukraine: a History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pg. 369

- Spór o Galicję Wschodnią 1914-1923 Ludwik Mroczka. Wydawnictwo Naukowe WSP, January, 1998 page 106-108

- Paul Robert Magocsi. (2002). The roots of Ukrainian nationalism: Galicia as Ukraine's Piedmont. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pg. 28

- Christopher Gilley (2006). A Simple Question of ‘Pragmatism’? Sovietophilism in the West Ukrainian Emigration in the 1920s Working Paper: Koszalin Institute of Comparative European Studies pp.6-16

- "Warsaw, Treaty of". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- Kubijovic, V. (1963). Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopedia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- State Secretariat of the Western Ukrainian National Republic Encyclopedia of Ukraine, (1993) vol. 5

- Jarosław Hrycak. (1996). Нариси Історії України: Формування модерної української нації XIX-XX ст Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine (Ukrainian; Essays on the History of Ukraine: the Formation of the Modern Ukrainian Nation). Kiev, Ukraine: Chapter 3.

- Social-Political Portrait of the Ukrainian Leadership of Galicia and Bokovyna during the Reovlutionary Years of 1918-1919 Oleh Pavlyshyn (2000). Modern Ukraine, volume 4-5

- Christoph Mick. (2015). Lemberg, Lwow, Lviv, 1914–1947: Violence and Ethnicity in a Contested City. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, pg. 177-184

- Bandera - romantyczny terrorysta "Bandera - Romantic Terrorist, interview with Jarosław Hrycak. Gazeta Wyborcza, May 10, 2008. Hrytsak, a history professor at Central European University states: "Before the First World War Ukrainian nationalism under Austrian rule was neither very xenophobic nor aggressive. It was anti-Polish, which was understandable, but not antisemitic."

- "Wojna na mapy" - "wojna na słowa". Onomastyczne i międzykulturowe aspekty polityki językowej II Rzeczpospolitej w stosunku do mniejszości ukraińskiej w Galicji Wschodniej w okresie międzywojennym page 106 Katarzyna Hibel LIT Verlag 2014

- „Niech nas rozsądzi miecz i krew.” ... Konflikt polsko-ukraiński o Galicję Wschodnią w latach 1918–1919, Poznań 2004, ISBN 83-7177-281-5, pages 145–146, 159-160

- Wojna polsko-ukraińska 1918-1919: działania bojowe, aspekty polityczne, kalendarium Grzegorz Łukomski, Czesław Partacz, Bogusław Polak Wydawn. Wyższej Szkoły Inżynierskiej w Koszalinie ; Warszawa, 1994 page 95-96

- Spór o Galicję Wschodnią 1914-1923 Ludwik Mroczka. Wydawnictwo Naukowe WSP, January, 1998 page 102

- Christoph Mick. (2015). Lemberg, Lwow, Lviv, 1914–1947: Violence and Ethnicity in a Contested City. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, pg. 175

- Lwów 1918-1919 Michał Klimecki Dom Wydawniczy Bellona, 1998, page 99

- Christoph Mick. (2015). Lemberg, Lwow, Lviv, 1914–1947: Violence and Ethnicity in a Contested City. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, pg. 150

- Konflikt polsko-ukraiński w prasie Polski Zachodniej w latach 1918-1923 Marek Figura Wydawn. Poznańskie,page 120, 2001

- Wojna polsko-ukraińska 1918-1919: działania bojowe, aspekty polityczne, kalendarium Grzegorz Łukomski, Czesław Partacz, Bogusław Polak Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Inżynierskiej w Koszalinie ; Warszawa, 1994 - 285 page 96 Kiedy w Brzuchowicach kolejarze polscy odmówili pracy, zostali rozstrzelani

- Udział duchowieństwa w polskim życiu politycznym w latach 1914-1924 page 300 Michał Piela RW KUL, 1994 - 359

- Czesław Partacz – Wojna polsko-ukraińska o Lwów i Galicję Wschodnią 1918-1919 Przemyskie Zapiski Historyczne – Studia i materiały poświęcone historii Polski Południowo-Wschodniej. 2006-09 R. XVI-XVII (2010) page 70

- Rafał Galuba. (2004) "Let the sword and the blood judge us ...". Polish-Ukrainian conflict of Eastern Galicia in 1918-1919. Poznan. ISBN 83-7177-281-5

- Christoph Mick. (2015). Lemberg, Lwow, Lviv, 1914–1947: Violence and Ethnicity in a Contested City. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, pg. 180

- Alexander Victor Prusin. (2005). Nationalizing a Borderland: War, ethnicity, and anti-Jewish violence in Eastern Galicia, 1914–1920. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, pp.97-101.

- Alexander V. Prusin. (2010). The Lands Between: Conflict in the East European Borderlands, 1870–1992. Oxford: Oxford University Press pg. 93

- Aharon Weiss. (1990). Jewish-Ukrainian Relations During the Holocaust. In Peter J. Potichnyj, Howard Aster (eds.) Ukrainian-Jewish relations in historical perspective. Edmonton, Alberta: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, pp.409-420.

- "Jewish Battalion of the Ukrainian Galician Army | Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 2". encyclopediaofukraine.com. 1989. Retrieved 2017-06-18.

- Michel Europa-Katalog Ost 1985/86, Westukraine

- John Bulat, Illustrated Postage Stamp History of Western Ukrainian Republic 1918–1919 (Yonkers, NY: Philatelic Publications, 1973).

- Kubijovic, V. (Ed.), Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopedia, University of Toronto Press: Toronto, Canada, 1963.

- Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-5808-6.

- Paul Robert Magocsi, A History of Ukraine, University of Toronto Press: Toronto 1996, ISBN 0-8020-0830-5.

- Tomasz J. Kopański, Wojna polsko-ukraińska 1918––1919 i jej bohaterowie, Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej, Warsaw 2013

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Western Ukrainian People's Republic. |

- Vasyl Markus, Matvii Stakhiv, Western Ukrainian National Republic in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 5 (1993)

- Dictatorship of the Western Province of the Ukrainian National Republic in the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, vol. 1 (1984)

- Short mention of ZUNR history

- Introduction to Ukrainian Philately

- People's war 1917–1932 by Kyiv city organization "Memorial"