Elsie Inglis

Elsie Maud Inglis (16 August 1864 – 26 November 1917) was an innovative Scottish doctor, pioneering surgeon, inspiring teacher,[1] suffragist, and founder of the Scottish Women's Hospitals,[2] and the first woman to hold the Serbian Order of the White Eagle.[3]

Elsie Maud Inglis | |

|---|---|

Elsie Inglis | |

| Born | 16 August 1864 Naini Tal, India |

| Died | 26 November 1917 (aged 53) |

| Resting place | Dean cemetery |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names | The Woman with the Torch |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Doctor |

| Known for | Suffragist; First World War doctor; campaigner for women and children's health |

| Honours | Serbian Order of the White Eagle (First Class) |

Early life and education

Elsie (Eliza) Maud Inglis was born on 16 August 1864, in the hill station town of Naini Tal, India. Inglis had eight siblings and was the second daughter and third youngest.[1] Her parents were Harriet Lowes Thompson and John Forbes David Inglis (1820–1894), a magistrate who worked in the Indian civil service as Chief Commissioner of Oudh through the East India Company,[4] as did her maternal grandfather. Inglis had the good fortune to have enlightened parents for the time who considered the education of a daughter as important as that of a son,[5] and unusually also had them schooled in India. Elsie and her sister Eva had 40 dolls which she used to treat for 'spots' (measles) she had painted on[1].

Inglis's father was religious and used his position in India to “encourage native economic development, spoke out against infanticide and promoted female education."[5]

Inglis's maternal grandfather was Rev Henry Simson of Garioch in Aberdeenshire.[6] She was a cousin to the eminent gynaecologist Sir Henry Simson. Another cousin was related by marriage to her peer and fellow female medical student Grace Cadell who was the first Scottish woman to obtain a medical licence.

Inglis's father retired (when aged 56) from the East India Company to return to Edinburgh, via Tasmania, where some of her older siblings settled.[1] Inglis went on to a private education in Edinburgh (where she had led a successful demand by the schoolgirls to use private gardens in Charlotte Square) and finishing school in Paris. Inglis's decision to study medicine was delayed by nursing her mother, during her last illness (scarlet fever)[1] and her death in 1885, when she felt obliged to stay in Edinburgh with her father.

In 1887, the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women was opened by Dr Sophia Jex-Blake and Inglis started her studies there. In reaction to Jex-Blake's uncompromising ways, and after two fellow students Grace and Georgina Cadell were expelled, Inglis and her father founded the Edinburgh College of Medicine for Women, under the auspices of the Scottish Association for the Medical Education of Women whose sponsors included Sir William Muir, a friend of her father from India, now Principal of the University of Edinburgh.[1] Inglis's sponsors also arranged clinical training for female students under Sir William MacEwen at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary.[4]

In 1892, she obtained the Triple Qualification, becoming a Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. She was appalled by the standard of care and lack of specialisation in the needs of female patients, and was able to obtain a post at Elizabeth Garrett Anderson's pioneering New Hospital for Women in London, and then at the Rotunda in Dublin, a leading maternity hospital. Inglis gained her MBChM qualification in 1899, from the University of Edinburgh, after it opened its medical courses to women.[4] Her return to Edinburgh to start this course had coincided with nursing her father in his final illness before he died on 4 March 1894, aged 73. Inglis at the time noted that 'he did not believe that death was the stopping-place, but that one would go on growing and learning through all eternity'.[1]

Inglis later acknowledged that 'whatever I am, whatever I have done - I owe it all to my father'.[1]

Career

Medical practice

Inglis returned to Edinburgh in 1894, completed her medical degree and became a lecturer in gynaecology at the Medical College for Women and then set up a medical practice with Jessie MacLaren MacGregor, who had been a fellow student, and recognising women and children's medicine was under resourced,[1] opened a maternity hospital, named The Hospice, for poor women alongside a midwifery resource and training centre, initially in George Square.[1] The Hospice was then provided with an accident and general service as well as maternity,[7] with an operating theatre and eight beds,[8] in new premises at 219 High Street, on the Royal Mile, close to Cockburn Street,[9] and was the forerunner of the Elsie Inglis Memorial Maternity Hospital. In 1913, Inglis travelled across to the USA (Michigan) to visit and learn from a new type of maternity hospital.[7]

A philanthropist, Inglis often waived the fees owed to her and would pay for her patients to recuperate by the sea-side, with polio being a particular childhood illness she was concerned with.[1] Inglis was a consultant at Bruntsfield Hospital for women and children, and despite a disagreement between Inglis and the hospital management, the Hospice joined forces with them in 1910.

Inglis surgical skills were recognised by colleagues as “she was quiet, calm, and collected, and never at a loss, skilful in her manipulations, and able to cope with any emergency.”[7]

Suffrage movement

Her dissatisfaction with the standard of medical care available to women led her to political activism through the suffrage movement. She was the secretary of the Edinburgh National Society for Women's Suffrage in the 1890s, supported by her father,[1] and while she was working toward her medical degree.[10]

Inglis worked closely with Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (the NUWSS), speaking at events all over the country. By 1906, "Elsie Inglis was to the Scottish groups what Mrs. Fawcett was to the English; when they too formed themselves that year into a Federation, it was Elsie who became its secretary."[11] From the early years of the Scottish Federation of Women's Suffrage Societies, Inglis was honorary secretary from 1906 and continued in this role right up to 1914.[12]

Like Fawcett, Inglis was a suffragist and not like the Pankhurst family, who were militant suffragettes.

A century later, in The Lancet, Lucy Inglis (a relative) noted Inglis had said 'fate had placed her in the van of a great movement' and was a 'keen fighter'.[7] Inglis's personal style was described by fellow suffragist Sarah Mair as 'courteous, sweet-voiced' with 'the eyes of a seer', a 'radiant smile' when her lips were not 'firmly closed with a fixity of purpose such as would warn off unwarrantable opposition or objections...'[1]

The Scottish Federation's most important initiative was the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service. Inglis felt that it was important for the hospitals to have a neutral name in order to attract "wide support from men and women".[13] Inglis was able to use her connections to the suffrage movement to raise money for the Scottish Women's Hospitals (SWH). Inglis first assumed that the Scottish Red Cross could help with funding, but the head of the Scottish Red Cross, Sir George Beatson denied Inglis’ request stating that the Red Cross was in the hands of the War Office and he could have “nothing to say to a hospital staffed by women.”[14]

To help get the ball rolling for the SWH, “she opened a fund with £100 of her own money.”[15] Milicent Fawcett, of NUWSS took up the cause and invited Inglis to speak about the SWH in London,[16] and by the next month, Inglis had her first £1,000.[17] The goal was £50,000.[18] Collection boxes had the NUWSS logo in small print, one is held in the National Museum of Scotland.[19]

Inglis's medical career overlapped into her suffrage involvement and her suffrage action overlapped into war work.

First World War

_and_some_of_her_sisters_-_1916.png)

Despite Inglis's already notable achievements, it was her efforts to treat the wounded at the front ( when already turning 50 at the start of)[16] during the First World War that brought her fame. Inglis was instrumental in setting up, despite government resistance, the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service Committee, an organisation funded by the women's suffrage movement with the express aim of providing all female staffed relief hospitals for the Allied war effort, including doctors and technical staff (paid) and others as volunteers.[16] The organisation was active in sending eventually 14 teams to Belgium, France, Serbia and Russia[20].[16]

When Inglis approached the Royal Army Medical Corps to offer them a ready-made medical unit staffed by qualified women, the War Office told her "Go home and sit still". It was, instead, the French government that took up her offer and established a unit in France and she led her own unit in Serbia.[21] Inglis was involved in all aspects of the organisation of this service down to the colours of the uniform 'a hodden grey, with Gordon tartan facings'.[22] The French hospital was based at the Abbey of Royaumont and was run by Frances Ivens from January 1915 to March 1919. Inglis had initially offered a 100-bed hospital but it grew to hold 600 beds as it coped with the severity of battles, including that on the Somme.[23]

Inglis went with the teams sent to Serbia, where her presence and work in improving hygiene reduced typhus and other epidemics that had been raging there. On her journey there she enjoyed a last peaceful day of sunshine and starlight on the voyage.[16] The hospital in Serbia was in the midst of a typhus outbreak, which eventually took the lives of four of the SWH staff, including Nurse Louisa Jordan, after whom the Covid19 (coronavirus) pandemic hospital in Glasgow was named in 2020.[16] Four SWH units in Serbia were established but in 1915 Inglis was captured, when the Austro-Hungarian and German forces took over the region, as she had stayed behind with others to repatriate the wounded. Inglis was taken prisoner when at Krushevatz (Krushevac) Hospital in Siberia. Inglis and others were repatriated via neutral Switzerland in February 1916,[16] but upon reaching Scotland, she at once began organising funds for a Scottish Women's Hospital team in Russia. She headed the team when it left for Odessa, Russia in August 1916, and worked alongside Serbs again there.[16] Two SWH units were under overcome in the chaos of a retreat with Inglis travelling via Dobruja to Braila, on the Danube. with a mixture of people in flight including families, doctors, soldiers and a Romanian officer who had been in Glasgow and knew 'British 'custims' (sic).[16] This absurdly comforted Inglis to think of her homeland 'there, quiet, strong and invincible, behind everything and everyone'.[22] At Braila with just six other doctors, only one surgeon, Inglis was involved in treating 11,000 wounded soldiers and sailors, many of whom were behind a letter in tribute to Inglis written in the name of 'The Russian Citizen Soldiers' written at Easter to 'express our sincere gratitude for all the care and attention bestowed on us, and we bow low before the tireless and wonderful work of yourself and your personnel, which we see every day directed towards the good of the soldiers allied to your country'.[22] Sadly, Inglis got news that her own nephew was shot in the head and blinded on the day she was leaving for Reni (Ukraine) which caused her to question the eternal battle of good and evil put about in wartime, as Inglis wrote to her sister expressing her sorrow for her nephew ending 'we are just here in it, and whatever we lose, it is for the right we are standing...it is all terrible and awful, and I don't believe we can disentangle it all in our minds just now. The only thing is just to go on doing our bit.'[16]

Inglis, 'an indomitable little figure' lasted a summer in Russia, before she too was forced to return in poor health to the United Kingdom, dying almost on arrival, suffering from bowel cancer. Her final journey with Serb officers being evacuated saw her stand on deck saying farewell to each one 'in quiet dignity.'[16]

Death and legacy

Inglis died on 26 November 1917, the day after she arrived back in England, at the Station Hotel, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Inglis's body lay in state at St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh, and her funeral there on 29 November was attended by both British and Serbian royalty. The service included the 'Hallelujah Chorus' and the Last Post played by the buglers of the Royal Scots. The streets were lined with people as her coffin went through Edinburgh to be buried at the Dean Cemetery.[16]

The Scotsman newspaper wrote that it was an "occasion of an impressive public tribute". Winston Churchill said of Inglis and her nurses "they will shine in history."[4][24]

A separate memorial service was held on 30 November in London, at St Margaret's Church in Westminster, the Anglican parish church of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom.

Inglis is buried in the north section of Dean Cemetery, on a corner north of the central path. Her parents, John Forbes David Inglis (1820–1894) and Harriet Lowes Thompson (1827–1885) lie a few graves to the north. Her cousin, Sir Henry Simson, lies adjacent.

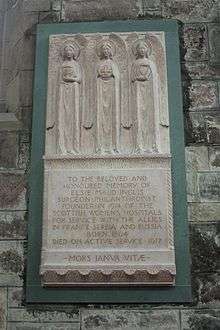

A memorial fountain was erected in Inglis's memory in Mladenovac, Serbia, commemorating her work for the country. A plaque marking her pre-war surgery from 1898 to 1914 was erected at 8 Walker Street, Edinburgh. A portrait of her is included in the mural of heroic women by Walter P. Starmer unveiled in 1921 in the church of St Jude-on-the-Hill in Hampstead Garden Suburb, London. In 1922 a large tablet to her memory (sculpted by Pilkington Jackson) was erected in the north aisle of St Giles Cathedral, in Edinburgh.

Her main physical memorial was the building of the Elsie Inglis Memorial Maternity Hospital in 1925 which was operational until 1988. This primarily ran as a maternity hospital and thereby had a female-only patient base. Many Edinburgh children were born there during the 20th century. It was closed by the National Health Service in 1988 and sold off. Part of it is now an old people's home, part is private housing, and parts are demolished; it is no longer recognisable as a hospital. At its closure there were public protests that a new maternity unit should also be named after Inglis, which has not yet happened (2020).[25] But a small plaque to Elsie Inglis exists near the south-west corner at the entrance to Holyrood Park.[9]

A nursing career development scheme in NHS Lothian is called 'the Elsies'.[25]

Inglis was commemorated on a new series of banknotes issued by the Clydesdale Bank in 2009; her image appeared on the new issue of £50 notes.[26][27] In March 2015, the British Residence in Belgrade was renamed 'Elsie Inglis House' in recognition of her work in the country.[28] The ceremony was conducted by the President of Serbia Tomislav Nikolic and the UK Ambassador Denis Keefe said

“Elsie Inglis was one of the first women in Scotland who had finished high education and was a pioneer of medicine. She fought energetically against prejudice, for social and political emancipation of women in Britain. She was also a tireless volunteer, courageous organiser of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals and a dedicated humanitarian. Unfortunately, Elsie Inglis didn’t live long enough to see the triumph of some of her ideas, but she has had a tremendous influence on social trends in our country. In Scotland she became a doctor, in Serbia she became a saint.”[25]

And in 2020 it is noted that Serbia's first palliative care hospice will also be named after Elsie Inglis.[25]

In November 2017, a memorial plaque to Elsie Inglis and 15 women who died as a result of their service to the Scottish Women's Hospitals was set in Edinburgh Central Library.[29]

Inglis's name and picture (and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters) are on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.[30][31][32]

Inglis's younger sister Eva Helen Shaw McLaren wrote her biography 'Elsie Inglis, The Woman With the Torch'[33][1] in 1920, and in 2009 a coloured illustrated edition was published,[34] a reference is to Florence Nightingale known as 'The Lady of the Lamp'. In Eva's papers was found an unpublished manuscript novel by Inglis, the Story of a Modern Woman whose heroine, Hildeguard Forrest, may be seen as autobiographical in part, and in a boating accident the narrator says 'in a sudden flash....[she] suddenly realised she wasn't a coward'.[1]

In the public eye, Inglis is possibly rated as one of the 'greatest-ever' Scottish women, 'a great role model and someone young Scots can be proud of'.[1] A journalist called on the Scottish Ministers to name Edinburgh' new (and troubled) Royal Hospital for Children and Young People after Elsie Inglis.[25]

Sir Winston Churchill wrote of the SWH ' No body of women has won a higher reputation in the Great War.....their work, lit up by the fame of Dr. Inglis, will shine in history'.[16]

Awards and honours

In April 1916, Inglis became the first woman to be awarded the Order of the White Eagle (First class) by the Crown Prince Alexander of Serbia at a ceremony in London.[4][3][35][36] She had previously been awarded the Order of Saint Sava (III class).[3]

Inglis (to date, 2020) has not been given any similar honours posthumously in the United Kingdom.

See also

References

- MacPherson, Hamish (5 May 2020). "Greatest Scot? The many talents of Dr Elsie Inglis". The National. p. 20. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

when she saw suffering or injustice she wanted to make a difference... and what she did paved the way for other women to come after her..... Alan Cumming in an interview with Nan Spowart on 11 November 2017 The National

- The National Archives. "The Discovery Service". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Serbian White Eagle: Scotswoman as the first woman recipient", Aberdeen Journal, 15 April 1916

- Ewan, Elizabeth; Innes, Sue; Reynolds, Siân; Pipes, Rose, eds. (2006). Inglis, Elsie Maude. The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 177–178. ISBN 9780748632930.

- Knox, William (2006). Lives of Scottish Women: Women and Scottish Society, 1800–1980. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 141.

- Simson/Inglis graves Dean Cemetery

- Inglis, Lucy (8 November 2014). "Elsie Inglis, the suffragette physician". The Lancet. 384 (9955): 1664–1665. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62022-5. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 25473677.

- Balfour, Frances (1919). Dr. Elsie Inglis. New York: George H. Doran Company (Nabu Public Domain Reprints). p. 182. ISBN 9781141571468.

- "The legacy of Elsie Inglis – Edinburgh's shame". The History Company. 6 February 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Leah Leneman, 'Inglis, Elsie Maud (1864–1917)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 6 June 2015

- Lawrence, Margot (1971). Shadow of Swords: A Biography of Elsie Inglis. Great Britain: Northhumberland Press Limited. p. 81.

- Lovejoy, Esther Pohl (1957). Women Doctors of the World. New York: Macmillan. p. 288.

- Leneman, Leah (1991). A Guid Cause: The Women's Suffrage Movement in Scotland. Aberdeen University Press. p. 211. ISBN 0 08 041201 7.

- Lawrence, Margot (1971). Shadow of Swords: A Biography of Elsie Inglis. London: Michael Joseph. p. 99. ISBN 071810871X.

- Sheffield Telegraph, 30 November 1917.

- MacPherson, Hamish (12 May 2020). "Dr Elsie Inglis and the legacy she left behind". The National. p. 20. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Common Cause, 30 October 1914.

- Lawrence, Margot (1971). Shadow of Swords: A Biography of Elsie Inglis. Great Britain: Nothumberland Press Limited. p. 100. ISBN 071810871X.

- "Collection box and medals, associated with Scottish Women's Hospitals units and Dr Elsie Inglis". National Museum of Scotland, via SCRAN search. 000-180-000-413-C.

- "Scottish Women's Hospital Unit". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Beauman, Nicola (2008). A very great profession : the woman's novel 1914–1939 (rev. ed.). London: Persephone Books. p. 23. ISBN 9781903155684.

- McLaren, Eva Shaw (1919). A History of the Scottish Women's Hospitals. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 8, 194, 210.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- "Doctor Eileen Crofton: Physician and author who uncovered a story of". The Independent. 14 October 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Lawrence, Margot (1971). Shadow of Swords: A Biography of Elsie Inglis. Great Britain: Northumberland Press Limited.

- "Scottish doctor found first human coronavirus case in 1960s". The National. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Banknote designs mark Homecoming". BBC News. 14 January 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- The Scotsman: "Bank proves Elsie Inglis was woman of (£50) note".

- "Serbia honours life of war doctor Elsie Inglis". Edinburgh Evening News. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- Pringle, Fiona (7 November 2017). "Memorial of Elsie Inglis set for Central Library". Edinburgh Evening News. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- "Historic statue of suffragist leader Millicent Fawcett unveiled in Parliament Square". Gov.uk. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- Topping, Alexandra (24 April 2018). "First statue of a woman in Parliament Square unveiled". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- "Millicent Fawcett statue unveiling: the women and men whose names will be on the plinth". iNews. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- McLaren, Eva Shaw (1920). Elsie Inglis: The Woman With the Torch. New York: Macmillan.

- McLaren, Eva Shaw (2009). Elsie Inglis: The Woman with The Torch (Illustrated Edition). Dodo Press. ISBN 9781409963530.

- "Calls to restore 'forgotten' Elsie Inglis grave", Edinburgh Evening News, 8 November 2013, retrieved 11 February 2014

- Medals and papers of Dr Elsie Inglis (PDF), Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh Library & Archive, 2009, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2014, retrieved 11 February 2014

Bibliography

- The archives of the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service are held at The Women's Library at the Library of the London School of Economics, ref 2SWH

- Leneman, Leah (1994). In the Service Of Life: The Story of Elsie Inglis and the Scottish Women’s Hospitals. Edinburgh: The Mercat Press.

- Leneman, Leah (1998). Elsie Inglis: Founder of battlefront hospitals run entirely by women. UK: NMS Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-901663-09-4.

- "Elsie Inglis". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford. 2004.

- Tait, Dr. H.P. (1964). Dr Elsie Maud Inglis, 1864-1917: A Great Lady Doctor. Bridgend, Wales: Bridgend Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elsie Inglis. |

- Short biography

- Bruntsfield Hospital and Elsie Inglis Memorial Maternity Hospital (Lothian Health Services Archive)

- The Scotsman archives

- Surgeons' Hall Museum, Edinburgh.

- University of Edinburgh

- Medical doctor and history, Documentary film – EAI

- Russian medical missions in Serbia during WW1, RTS Documentary

.jpg)