Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555)

The Ottoman–Safavid War of 1532–1555 was one of the many military conflicts fought between the two arch rivals, the Ottoman Empire led by Suleiman the Magnificent, and the Safavid Empire led by Tahmasp I.

| Ottoman-Safavid War of 1532–1555 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman–Persian Wars | |||||||||

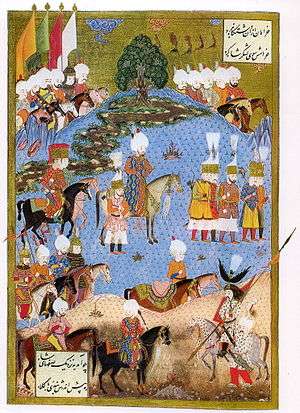

Miniature from the Süleymanname depicting Suleiman marching with an army in Nakhchivan, summer 1554, at the end of the Ottoman-Safavid War. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

60,000 men 10 pieces of artillery |

200,000 men 300 pieces of artillery | ||||||||

Background

The war was triggered by territorial disputes between the two empires, especially when the Bey of Bitlis decided to put himself under Persian protection.[6] Also, Tahmasp had the governor of Baghdad, a sympathiser of Suleiman, assassinated.

On the diplomatic front, Safavids had been engaged in discussions with the Habsburgs for the formation of a Habsburg-Persian alliance that would attack the Ottoman Empire on two fronts.[6]

Campaign of the Two Iraqs (First campaign, 1532–1536)

The Ottomans, first under the Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha, and later joined by Suleiman himself, successfully attacked Safavid Iraq, recaptured Bitlis, and proceeded to capture Tabriz and then Baghdad in 1534.[6] Tahmasp remained elusive as he kept retreating ahead of the Ottoman troops, adopting a scorched earth strategy.

Second campaign (1548–1549)

Under the Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha, Ottomans attempting to defeat the Shah once and for all, Suleiman embarked upon a second campaign in 1548–1549. Again, Tahmasp adopted a scorched earth policy, laying waste to Armenia. Meanwhile, the French king Francis I, enemy of the Habsburgs, and Suleiman the Magnificent were moving forward with a Franco-Ottoman alliance, formalized in 1536, that would counterbalance the Habsburg threat. In 1547, when Suleiman attacked Persia, France sent its ambassador Gabriel de Luetz, to accompany him in his campaign.[7] Gabriel de Luetz gave military advice to Suleiman, as when he advised on artillery placement during the Siege of Van.[7] Suleiman made gains in Tabriz, Persian ruled Armenia, secured a lasting presence in the province of Van in Eastern Anatolia, and took some forts in Georgia.

Third campaign (1553–1555) and aftermath

In 1553 The Ottomans, first under the Grand Vizier Rustem Pasha, and later joined by Suleiman himself, began his third and final campaign against the Shah, in which he first lost and then regained Erzurum. Ottoman territorial gains were secured by the Peace of Amasya in 1555. Suleiman returned Tabriz, but kept Baghdad, lower Mesopotamia, western Armenia, western Georgia, the mouths of the Euphrates and Tigris, and part of the Persian Gulf coast. Persia retained the rest of all its northwestern territories in the Caucasus.

Due to his heavy commitment in Persia, Suleiman was only able to send limited naval support to France in the Franco-Ottoman Invasion of Corsica (1553).

Notes

- Gábor Ágoston-Bruce Masters:Encyclopaedia of the Ottoman Empire , ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1, p.280

- The Reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, 1520–1566, V.J. Parry, A History of the Ottoman Empire to 1730, ed. M.A. Cook (Cambridge University Press, 1976), 94.

- A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East, Vol. II, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010). 516.

- Ateş, Sabri (2013). Ottoman-Iranian Borderlands: Making a Boundary, 1843–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-1107245082.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 698. ISBN 978-1598843361.

- The Cambridge history of Islam by Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis p. 330

- The Cambridge history of Iran by William Bayne Fisher p.384ff

Sources

- Yves Bomati and Houchang Nahavandi,Shah Abbas, Emperor of Persia,1587–1629, 2017, ed. Ketab Corporation, Los Angeles, ISBN 978-1595845672, English translation by Azizeh Azodi.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. xxxi. ISBN 978-1442241466.

French ambassador Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramon participated in the Ottoman campaign.

French ambassador Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramon participated in the Ottoman campaign..jpg) The walled city of Van, which Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramon helped conquer.

The walled city of Van, which Gabriel de Luetz d'Aramon helped conquer.