Wahhabism

Wahhabism (Arabic: الوهابية, al-Wahhābiyah) is an Islamic doctrine and religious movement founded by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab.[lower-alpha 1] It has been variously described as "ultraconservative", "far-right"[1] "austere",[2] "fundamentalist",[3] or "puritan(ical)";[4][5] as an Islamic "reform movement" to restore "pure monotheistic worship" (tawhid) by devotees;[6][7] and as a "deviant sectarian movement",[7] "vile sect"[8] and a distortion of Islam by its detractors.[2][9] The term Wahhabism is often used polemically and adherents commonly reject its use, preferring to be called Salafi or muwahhid,[10][11][12] claiming to emphasize the principle of tawhid[13] (the "uniqueness" and "unity" of God)[14] or monotheism, dismissing other Muslims as practising shirk (idolatry).[15] It follows the theology of Ibn Taymiyyah and the Hanbali school of jurisprudence,[6] although a small minority of Hanbali leaders renounced ibn Abd al-Wahhab's views due to Ottoman influence.[5]

| Part of a series on:

Salafi movement |

|---|

Sab'u Masajid, Saudi Arabia |

|

Ideology and influences |

|

Founders and key figures |

|

Notable universities |

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

In terms of Ihsan |

|

|

|

Lists |

|

|

Wahhabism is named after an eighteenth-century Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher and activist, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792).[6][16][17][18][19] He started a reform movement in the remote, sparsely populated region of Najd,[6][20] advocating a purging of such widespread Sunni practices as the veneration of saints and the visiting of their tombs and shrines, that were practiced all over the Islamic world, but which he considered idolatrous impurities and innovations in Islam (bid'ah).[6][14][21] Eventually he formed a pact with a local leader, Muhammad bin Saud, offering political obedience and promising that protection and propagation of the Wahhabi movement meant "power and glory" and rule of "lands and men".[22]

The alliance between followers of ibn Abd al-Wahhab and Muhammad bin Saud's successors (the House of Saud) proved to be a durable one. The House of Saud continued to maintain its politico-religious alliance with the Wahhabi sect through the waxing and waning of its own political fortunes over the next 150 years, through to its eventual proclamation of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932, and then afterwards, on into modern times. Today Ibn Abd Al-Wahhab's teachings are the official, state-sponsored form of Sunni Islam[2][23] in Saudi Arabia.[24] With the help of funding from Saudi petroleum exports[25] (and other factors[26]), the movement underwent "explosive growth" beginning in the 1970s and now has worldwide influence.[2] The US State Department has estimated that over the past four decades concerns in Riyadh have directed at least $10bn (£6bn) to select charitable foundations toward the subversion of mainstream Sunni Islam by Wahhabism.[27] (As of 2017 changes to Saudi religious policy by Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman have led some to suggest that "Islamists throughout the world will have to follow suit or risk winding up on the wrong side of orthodoxy".[28])

The "boundaries" of Wahhabism have been called "difficult to pinpoint",[29] but in contemporary usage, the terms Wahhabi and Salafi are often used interchangeably, and they are considered to be movements with different roots that have merged since the 1960s.[30][31][32] However, Wahhabism has also been called "a particular orientation within Salafism",[33] or an ultra-conservative, Saudi brand of Salafism.[34][35] Estimates of the number of adherents to Wahhabism vary, with one source (Mehrdad Izady) giving a figure of fewer than 5 million Wahhabis in the Persian Gulf region (compared to 28.5 million Sunnis and 89 million Shia).[24][36]

The majority of Sunni and Shia Muslims worldwide disagree with the interpretation of Wahhabism, and many Muslims denounce them as a faction or a "vile sect".[8] Islamic scholars, including those from the Al-Azhar University, regularly denounce Wahhabism with terms such as "Satanic faith".[37] Wahhabism has been accused of being "a source of global terrorism",[38][39] inspiring the ideology of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL),[40] and for causing disunity in Muslim communities by labelling Muslims who disagreed with the Wahhabi definition of monotheism as apostates[6][41] (takfir) and justifying their killing.[42][43][44] It has also been criticized for the destruction of historic shrines of saints, mausoleums, and other Muslim and non-Muslim buildings and artifacts.[45][46][47]

Definitions and etymology

Definitions

Some definitions or uses of the term Wahhabi Islam include:

- "a corpus of doctrines", and "a set of attitudes and behavior, derived from the teachings of a particularly severe religious reformist who lived in central Arabia in the mid-eighteenth century" (Gilles Kepel)[48]

- "pure Islam" (David Commins, paraphrasing supporters' definition),[9] that does not deviate from Sharia law in any way and should be called Islam and not Wahhabism. (King Salman bin Abdul Aziz, King of Saudi Arabia)[49]

- "a misguided creed that fosters intolerance, promotes simplistic theology, and restricts Islam's capacity for adaption to diverse and shifting circumstances" (David Commins, paraphrasing opponents' definition)[9]

- "a conservative reform movement ... the creed upon which the kingdom of Saudi Arabia was founded, and [which] has influenced Islamic movements worldwide" (Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim world)[50]

- "a sect dominant in Saudi Arabia and Qatar" with footholds in "India, Africa, and elsewhere", with a "steadfastly fundamentalist interpretation of Islam in the tradition of Ibn Hanbal" (Cyril Glasse)[13]

- an "eighteenth-century reformist/revivalist movement for sociomoral reconstruction of society", "founded by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab" (Oxford Dictionary of Islam).[51]

- originally a "literal revivification" of Islamic principles that ignored the spiritual side of Islam, that "rose on the wings of enthusiasm and longing and then sank down into the lowlands of pharisaic self-righteousness" after gaining power and losing its "longing and humility" (Muhammad Asad)[52]

- "a political trend" within Islam that "has been adopted for power-sharing purposes", but cannot be called a sect because "It has no special practices, nor special rites, and no special interpretation of religion that differ from the main body of Sunni Islam" (Abdallah Al Obeid, the former dean of the Islamic University of Medina and member of the Saudi Consultative Council)[29]

- "the true salafist movement". Starting out as a theological reform movement, it had "the goal of calling (da'wa) people to restore the 'real' meaning of tawhid (oneness of God or monotheism) and to disregard and deconstruct 'traditional' disciplines and practices that evolved in Islamic history such as theology and jurisprudence and the traditions of visiting tombs and shrines of venerated individuals." (Ahmad Moussalli)[53]

- a term used by opponents of Salafism in hopes of besmirching that movement by suggesting foreign influence and "conjuring up images of Saudi Arabia". The term is "most frequently used in countries where Salafis are a small minority" of the Muslim community but "have made recent inroads" in "converting" the local population to Salafism. (Quintan Wiktorowicz)[10]

- a blanket term used inaccurately to refer to "any Islamic movement that has an apparent tendency toward misogyny, militantism, extremism, or strict and literal interpretation of the Quran and hadith" (Natana J. DeLong-Bas)[54]

Etymology

According to Saudi writer Abdul Aziz Qassim and others, it was the Ottomans who "first labelled Abdul Wahhab's school of Islam in Saudi Arabia as Wahhabism". The British also adopted it and expanded its use in the Middle East.[55] The term Wahhabi should not be confused to Wahbi which is the dominant creed within Ibadism.[56]

Naming controversy: Wahhabis, Muwahhidun, and Salafis

Wahhabis do not like – or at least did not like – the term. Ibn Abd-Al-Wahhab was averse to the elevation of scholars and other individuals, including using a person's name to label an Islamic school.[10][42][57]

According to Robert Lacey "the Wahhabis have always disliked the name customarily given to them" and preferred to be called Muwahhidun (Unitarians).[58] Another preferred term was simply "Muslims" since their creed is "pure Islam".[59] However, critics complain these terms imply non-Wahhabis are not monotheists or Muslims.[59][60] Additionally, the terms Muwahhidun and Unitarians are associated with other sects, both extant and extinct.[61]

Other terms Wahhabis have been said to use and/or prefer include ahl al-hadith ("people of hadith"), Salafi Da'wa or al-da'wa ila al-tawhid[62] ("Salafi preaching" or "preaching of monotheism", for the school rather than the adherents) or Ahl ul-Sunna wal Jama'a ("people of the tradition of Muhammad and the consensus of the Ummah"),[33] Ahl al-Sunnah ("People of the Sunna"),[63] or "the reform or Salafi movement of the Sheikh" (the sheikh being ibn Abdul-Wahhab).[64] Early Salafis referred to themselves simply as "Muslims", believing the neighboring Ottoman Caliphate was al-dawlah al-kufriyya (a heretical nation) and its self-professed Muslim inhabitants actually non-Muslim.[41][65][66] The self-designation as "People of the Sunna" was important for Wahhabisms authencity, because during the Ottoman period only Sunnism was the legitimate doctrine.[67]

Many, such as writer Quinton Wiktorowicz, urge use of the term Salafi, maintaining that "one would be hard pressed to find individuals who refer to themselves as Wahhabis or organizations that use 'Wahhabi' in their title, or refer to their ideology in this manner (unless they are speaking to a Western audience that is unfamiliar with Islamic terminology, and even then usage is limited and often appears as 'Salafi/Wahhabi')".[10] A New York Times journalist writes that Saudis "abhor" the term Wahhabism, "feeling it sets them apart and contradicts the notion that Islam is a monolithic faith".[68] Saudi King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud for example has attacked the term as "a doctrine that doesn't exist here (Saudi Arabia)" and challenged users of the term to locate any "deviance of the form of Islam practiced in Saudi Arabia from the teachings of the Quran and Prophetic Hadiths".[69][70] Ingrid Mattson argues that "'Wahhbism' is not a sect. It is a social movement that began 200 years ago to rid Islam of rigid cultural practices that had (been) acquired over the centuries."[71]

On the other hand, according to authors at Global Security and Library of Congress the term is now commonplace and used even by Wahhabi scholars in the Najd,[21][72] a region often called the "heartland" of Wahhabism.[73] Journalist Karen House calls 'Salafi' "a more politically correct term" for 'Wahhabi'.[74]

In any case, according to Lacey, none of the other terms have caught on, and so like the Christian Quakers, Wahhabis have "remained known by the name first assigned to them by their detractors".[58]

Wahhabis and Salafis

Many scholars and critics distinguish between Wahhabi and Salafi. According to American scholar Christopher M. Blanchard,[75] Wahhabism refers to "a conservative Islamic creed centered in and emanating from Saudi Arabia", while Salafiyya is "a more general puritanical Islamic movement that has developed independently at various times and in various places in the Islamic world".[42]

However, many call Wahhabism a more strict, Saudi form of Salafi.[76][77] Wahhabism is the Saudi version of Salafism, according to Mark Durie, who states Saudi leaders "are active and diligent" in using their considerable financial resources "in funding and promoting Salafism all around the world".[78] Ahmad Moussalli tends to agree Wahhabism is a subset of Salafism, saying "As a rule, all Wahhabis are salafists, but not all salafists are Wahhabis."[53]

Hamid Algar lists three "elements" Wahhabism and Salafism had in common.

- above all disdain for all developments subsequent to al-Salaf al-Salih (the first two or three generations of Islam),

- the rejection of Sufism, and

- the abandonment of consistent adherence to one of the four or five Sunni Madhhabs (schools of fiqh).

And "two important and interrelated features" that distinguished Salafis from the Wahhabis:

- a reliance on attempts at persuasion rather than coercion in order to rally other Muslims to their cause; and

- an informed awareness of the political and socio-economic crises confronting the Muslim world.[79]

Hamid Algar and another critic, Khaled Abou El Fadl, argue Saudi oil-export funding "co-opted" the "symbolism and language of Salafism", during the 1960s and 70s, making them practically indistinguishable by the 1970s,[80] and now the two ideologies have "melded". Abou El Fadl believes Wahhabism rebranded itself as Salafism knowing it could not "spread in the modern Muslim world" as Wahhabism.[30]

History

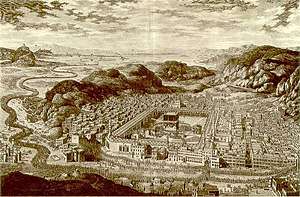

The Wahhabi mission started as a revivalist movement in the remote, arid region of Najd. With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, the Al Saud dynasty, and with it Wahhabism, spread to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. After the discovery of petroleum near the Persian Gulf in 1939, it had access to oil export revenues, revenue that grew to billions of dollars. This money – spent on books, media, schools, universities, mosques, scholarships, fellowships, lucrative jobs for journalists, academics and Islamic scholars – gave Wahhabism a "preeminent position of strength" in Islam around the world.[81]

In the country of Wahhabism's founding – and by far the largest and most powerful country where it is the state religion – Wahhabi ulama gained control over education, law, public morality and religious institutions in the 20th century, while permitting as a "trade-off" doctrinally objectionable actions such as the import of modern technology and communications, and dealings with non-Muslims, for the sake of the consolidation of the power of its political guardian, the Al Saud dynasty.[82]

However, in the last couple of decades of the twentieth century several crises worked to erode Wahhabi "credibility" in Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Muslim world – the November 1979 seizure of the Grand Mosque by militants; the deployment of US troops in Saudi Arabia during the 1991 Gulf War against Iraq; and the 9/11 2001 al-Qaeda attacks on New York and Washington.[83]

In each case the Wahhabi establishment was called on to support the dynasty's efforts to suppress religious dissent – and in each case it did[83] – exposing its dependence on the Saudi dynasty and its often unpopular policies.[84][85]

In the West, the end of the Cold War and the anti-communist alliance with conservative, religious Saudi Arabia, and the 9/11 attacks created enormous distrust towards the kingdom and especially its official religion.[86]

Muhammad ibn Abd-al-Wahhab

The founder of Wahhabism, Mohammad ibn Abd-al-Wahhab, was born around 1702–03 in the small oasis town of 'Uyayna in the Najd region, in what is now central Saudi Arabia.[87] He studied in Basra,[88] in what is now Iraq, and possibly Mecca and Medina while there to perform Hajj, before returning to his home town of 'Uyayna in 1740. There he worked to spread the call (da'wa) for what he believed was a restoration of true monotheistic worship (Tawhid).[89]

The "pivotal idea" of Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's teaching was that people who called themselves Muslims but who participated in alleged innovations were not just misguided or committing a sin, but were "outside the pale of Islam altogether", as were Muslims who disagreed with his definition. [90]

This included not just lax, unlettered, nomadic Bedu, but also Shias and Sunnis such as the Ottomans.[91] Such infidels were not to be killed outright, but to be given a chance to repent first.[92] With the support of the ruler of the town – Uthman ibn Mu'ammar – he carried out some of his religious reforms in 'Uyayna, including the demolition of the tomb of Zayd ibn al-Khattab, one of the Sahaba (companions) of the prophet Muhammad, and the stoning to death of an adulterous woman. However, a more powerful chief (Sulaiman ibn Muhammad ibn Ghurayr) pressured Uthman ibn Mu'ammar to expel him from 'Uyayna.[93]

When Muhammad started preaching the manhaj of the Salaf-as-saliheen in the Ottoman controlled Hejaz, where veneration of saints and superstitions became prevalent, he was initially rejected and called "deviant". But, later his call to dawah became extremely popular. The fact based account is presented in the book "The Wahhabi Myth" by Haneef James Oliver.[94]

Alliance with the House of Saud

The ruler of a nearby town, Muhammad ibn Saud, invited ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab to join him, and in 1744 a pact was made between the two. [95] Ibn Saud would protect and propagate the doctrines of the Wahhabi mission, while ibn Abdul Wahhab "would support the ruler, supplying him with 'glory and power'". Whoever championed his message, ibn Abdul Wahhab promised, "will, by means of it, rule the lands and men". [22] Ibn Saud would abandon un-Sharia taxation of local harvests, and in return God might compensate him with booty from conquest and sharia compliant taxes that would exceed what he gave up.[96] The alliance between the Wahhabi mission and Al Saud family has "endured for more than two and half centuries", surviving defeat and collapse.[95][97] The two families have intermarried multiple times over the years and in today's Saudi Arabia, the minister of religion is always a member of the Al ash-Sheikh family, i.e., a descendant of Ibn Abdul Wahhab.[98]

According to most sources, Ibn Abd al-Wahhab declared jihad against neighboring tribes, whose practices of asking saints for their intercession, making pilgrimages to tombs and special mosques, he believed to be the work of idolaters/unbelievers.[43][60][92][99]

One academic disputes this. According to Natana DeLong-Bas, Ibn Abd al-Wahhab was restrained in urging fighting with perceived unbelievers, preferring to preach and persuade rather than attack.[100] [101][102] It was only after the death of Muhammad bin Saud in 1765 that, according to DeLong-Bas, Muhammad bin Saud's son and successor, Abdulaziz bin Muhammad, used a "convert or die" approach to expand his domain,[103] and when Wahhabis adopted the takfir ideas of Ibn Taymiyya.[104]

However, various scholars, including Simon Ross Valentine, have strongly rejected such a view of Wahhab, arguing that "the image of Abd’al-Wahhab presented by DeLong-Bas is to be seen for what it is, namely a re-writing of history that flies in the face of historical fact".[105] Conquest expanded through the Arabian Peninsula until it conquered Mecca and Medina in the early 19th century.[106][107] It was at this time, according to DeLong-Bas, that Wahhabis embraced the ideas of Ibn Taymiyya, which allow self-professed Muslims who do not follow Islamic law to be declared non-Muslims – to justify their warring and conquering the Muslim Sharifs of Hijaz.[104]

One of their most noteworthy and controversial attacks was on Karbala in 1802. There, according to a Wahhabi chronicler 'Uthman b. 'Abdullah b. Bishr: "The Muslims" – as the Wahhabis referred to themselves, not feeling the need to distinguish themselves from other Muslims, since they did not believe them to be Muslims –

scaled the walls, entered the city ... and killed the majority of its people in the markets and in their homes. [They] destroyed the dome placed over the grave of al-Husayn [and took] whatever they found inside the dome and its surroundings ... the grille surrounding the tomb which was encrusted with emeralds, rubies, and other jewels ... different types of property, weapons, clothing, carpets, gold, silver, precious copies of the Qur'an.[108][109]

After this, the Wahhabis also massacred the male population and enslaved the women and children of the predominantly Sunni city of Ta'if in Hejaz in 1803.[110]

Saud bin Abdulaziz bin Muhammad bin Saud managed to establish his rule over southeastern Syria between 1803 and 1812. However, Egyptian forces acting under the Ottoman Empire and led by Ibrahim Pasha, were eventually successful in counterattacking in a campaign starting from 1811.[111] In 1818 they defeated Al-Saud, leveling the capital Diriyah, executing the Al-Saud emir and exiling the emirate's political and religious leadership,[97][112] and otherwise unsuccessfully attempted to stamp out not just the House of Saud but the Wahhabi mission as well.[113]

A second, smaller Saudi state (Emirate of Nejd) lasted from 1819 to 1891. Its borders being within Najd, Wahhabism was protected from further Ottoman or Egyptian campaigns by the Najd's isolation, lack of valuable resources, and that era's limited communication and transportation.[114]

By the 1880s, at least among townsmen if not Bedouin, Wahhabi strict monotheistic doctrine had become the native religious culture of the Najd.[115]

Abdulaziz Ibn Saud

In 1901, Abdulaziz Ibn Saud, a fifth generation descendant of Muhammad ibn Saud,[116] began a military campaign that led to the conquest of much of the Arabian peninsula and the founding of present-day Saudi Arabia, after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.[117] The result that safeguarded the vision of Islam-based on the tenets of Islam as preached by Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab was not bloodless, as 40,000 public executions and 350,000 amputations were carried out during its course, according to some estimates.[118][119][120][121]

Under the reign of Abdulaziz, "political considerations trumped religious idealism" favored by pious Wahhabis. His political and military success gave the Wahhabi ulama control over religious institutions with jurisdiction over considerable territory, and in later years Wahhabi ideas formed the basis of the rules and laws concerning social affairs, and shaped the kingdom's judicial and educational policies.[122] But protests from Wahhabi ulama were overridden when it came to consolidating power in Hijaz and al-Hasa, avoiding clashes with the great power of the region (Britain), adopting modern technology, establishing a simple governmental administrative framework, or signing an oil concession with the U.S. [123] The Wahhabi ulama also issued a fatwa affirming that "only the ruler could declare a jihad"[124] (a violation of Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's teaching, according to DeLong-Bas[101]),

As the realm of Wahhabism expanded under Ibn Saud into areas of Shiite (al-Hasa, conquered in 1913) and pluralistic Muslim tradition (Hejaz, conquered in 1924–25), Wahhabis pressed for forced conversion of Shia and an eradication of (what they saw as) idolatry. Ibn Saud sought "a more relaxed approach".[125]

In al-Hasa, efforts to stop the observance of Shia religious holidays and replace teaching and preaching duties of Shia clerics with Wahhabi, lasted only a year.[126]

In Mecca and Jeddah (in Hejaz) prohibition of tobacco, alcohol, playing cards and listening to music on the phonograph was looser than in Najd. Over the objections of Wahhabi ulama, Ibn Saud permitted both the driving of automobiles and the attendance of Shia at hajj.[127]

Enforcement of the commanding right and forbidding wrong, such as enforcing prayer observance and separation of the sexes, developed a prominent place during the second Saudi emirate, and in 1926 a formal committee for enforcement was founded in Mecca.[13][128] [129]

While Wahhabi warriors swore loyalty to monarchs of Al Saud, there was one major rebellion. King Abdulaziz put down rebelling Ikhwan – nomadic tribesmen turned Wahhabi warriors who opposed his "introducing such innovations as telephones, automobiles, and the telegraph" and his "sending his son to a country of unbelievers (Egypt)". [130] Britain had aided Abdulaziz, and when the Ikhwan attacked the British protectorates of Transjordan, Iraq and Kuwait, as a continuation of jihad to expand the Wahhabist realm, Abdulaziz struck, killing hundreds before the rebels surrendered in 1929.[131]

Connection with the outside

Before Abdulaziz, during most of the second half of the 19th century, there was a strong aversion in Wahhabi lands to mixing with "idolaters" (which included most of the Muslim world). Voluntary contact was considered by Wahhabi clerics to be at least a sin, and if one enjoyed the company of idolaters, and "approved of their religion", an act of unbelief.[132] Travel outside the pale of Najd to the Ottoman lands "was tightly controlled, if not prohibited altogether".[133]

Over the course of its history, however, Wahhabism has become more accommodating towards the outside world.[134] In the late 1800s, Wahhabis found Muslims with at least similar beliefs – first with Ahl-i Hadith in India,[135] and later with Islamic revivalists in Arab states (one being Mahmud Sahiri al-Alusi in Baghdad).[136] The revivalists and Wahhabis shared a common interest in Ibn Taymiyya's thought, the permissibility of ijtihad, and the need to purify worship practices of innovation.[137] In the 1920s, Rashid Rida, a pioneer Salafist whose periodical al-Manar was widely read in the Muslim world, published an "anthology of Wahhabi treatises", and a work praising the Ibn Saud as "the savior of the Haramayn [the two holy cities] and a practitioner of authentic Islamic rule".[138][139]

In a bid "to join the Muslim mainstream and to erase the reputation of extreme sectarianism associated with the Ikhwan", in 1926 Ibn Saud convened a Muslim congress of representatives of Muslim governments and popular associations.[140] By the early 1950s, the "pressures" on Ibn Saud of controlling the regions of Hejaz and al-Hasa – "outside the Wahhabi heartland" – and of "navigating the currents of regional politics" "punctured the seal" between the Wahhabi heartland and the "land of idolatry" outside.[141][142]

A major current in regional politics at that time was secular nationalism, which, with Gamal Abdul Nasser, was sweeping the Arab world. To combat it, Wahhabi missionary outreach worked closely with Saudi foreign policy initiatives. In May 1962, a conference in Mecca organized by Saudis discussed ways to combat secularism and socialism. In its wake, the World Muslim League was established.[143] To propagate Islam and "repel inimical trends and dogmas", the League opened branch offices around the globe.[144] It developed closer association between Wahhabis and leading Salafis, and made common cause with the Islamic revivalist Muslim Brotherhood, Ahl-i Hadith and the Jamaat-i Islami, combating Sufism and "innovative" popular religious practices[143] and rejecting the West and Western "ways which were so deleterious of Muslim piety and values".[145] Missionaries were sent to West Africa, where the League funded schools, distributed religious literature, and gave scholarships to attend Saudi religious universities. One result was the Izala Society which fought Sufism in Nigeria, Chad, Niger, and Cameroon.[146]

An event that had a great effect on Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia[147] was the "infiltration of the transnationalist revival movement" in the form of thousands of pious, Islamist Arab Muslim Brotherhood refugees from Egypt following Nasser's clampdown on the Brotherhood[148] (and also from similar nationalist clampdowns in Iraq[149] and Syria[150]), to help staff the new school system of the (largely illiterate) Kingdom.[151]

The Brotherhood's Islamist ideology differed from the more conservative Wahhabism which preached loyal obedience to the king. The Brotherhood dealt in what one author (Robert Lacey) called "change-promoting concepts" like social justice and anticolonialism, and gave "a radical, but still apparently safe, religious twist" to the Wahhabi values Saudi students "had absorbed in childhood". With the Brotherhood's "hands-on, radical Islam", jihad became a "practical possibility today", not just part of history.[152]

The Brethren were ordered by the Saudi clergy and government not to attempt to proselytize or otherwise get involved in religious doctrinal matters within the Kingdom, but nonetheless "took control of Saudi Arabia's intellectual life" by publishing books and participating in discussion circles and salons held by princes.[153] In time they took leading roles in key governmental ministries,[154] and had influence on education curriculum.[155] An Islamic university in Medina created in 1961 to train – mostly non-Saudi – proselytizers to Wahhabism[156] became "a haven" for Muslim Brother refugees from Egypt.[157] The Brothers' ideas eventually spread throughout the kingdom and had great effect on Wahhabism – although observers differ as to whether this was by "undermining" it[147][158] or "blending" with it.[159][160]

Growth

In the 1950s and 60s within Saudi Arabia, the Wahhabi ulama maintained their hold on religious law courts, and presided over the creation of Islamic universities and a public school system which gave students "a heavy dose of religious instruction".[161] Outside of Saudi the Wahhabi ulama became "less combative" toward the rest of the Muslim world. In confronting the challenge of the West, Wahhabi doctrine "served well" for many Muslims as a "platform" and "gained converts beyond the peninsula".[161][162]

A number of reasons have been given for this success: the growth in popularity and strength of both Arab nationalism (although Wahhabis opposed any form of nationalism as an ideology, Saudis were Arabs, and their enemy the Ottoman caliphate was ethnically Turkish),[26] and Islamic reform (specifically reform by following the example of those first three generations of Muslims known as the Salaf);[26] the destruction of the Ottoman Empire which sponsored their most effective critics;[163] the destruction of another rival, the Khilafa in Hejaz, in 1925.[26]

Not least in importance was the money Saudi Arabia earned from exporting oil.[81]

Petroleum export era

The pumping and export of oil from Saudi Arabia started during World War II, and its earnings helped fund religious activities in the 1950s and 60s. But it was the 1973 oil crisis and quadrupling in the price of oil that both increased the kingdom's wealth astronomically and enhanced its prestige by demonstrating its international power as a leader of OPEC. By 1980, Saudi Arabia was earning every three days the income from oil it had taken a year to earn before the embargo.[164] Tens of billions of US dollars of this money were spent on books, media, schools, scholarships for students (from primary to post-graduate), fellowships and subsidies to reward journalists, academics and Islamic scholars, the building of hundreds of Islamic centers and universities, and over one thousand schools and one thousand mosques.[165][166] [167] During this time, Wahhabism attained what Gilles Kepel called a "preeminent position of strength in the global expression of Islam".[81]

Afghanistan jihad

The "apex of cooperation" between Wahhabis and Muslim revivalist groups was the Afghan jihad.[168]

In December 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. Shortly thereafter, Abdullah Yusuf Azzam, a Muslim Brother cleric with ties to Saudi religious institutions,[169] issued a fatwa[170] declaring defensive jihad in Afghanistan against the atheist Soviet Union, "fard ayn", a personal (or individual) obligation for all Muslims. The edict was supported by Saudi Arabia's Grand Mufti (highest religious scholar), Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz, among others.[171][172]

Between 1982 and 1992 an estimated 35,000 individual Muslim volunteers went to Afghanistan to fight the Soviets and their Afghan regime. Thousands more attended frontier schools teeming with former and future fighters. Somewhere between 12,000 and 25,000 of these volunteers came from Saudi Arabia.[173] Saudi Arabia and the other conservative Gulf monarchies also provided considerable financial support to the jihad – $600 million a year by 1982.[174]

By 1989, Soviet troops had withdrawn and within a few years the pro-Soviet regime in Kabul had collapsed.

This Saudi/Wahhabi religious triumph further stood out in the Muslim world because many Muslim-majority states (and the PLO) were allied with the Soviet Union and did not support the Afghan jihad.[175] But many jihad volunteers (most famously Osama bin Laden) returning home to Saudi Arabia and elsewhere were often radicalized by Islamic militants who were "much more extreme than their Saudi sponsors".[175]

"Erosion" of Wahhabism

Islamic Revolution in Iran

The February 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran challenged Saudi Wahhabism in a number of ways on a number of fronts. It was a revolution of Shia, not Sunni, and Wahhabism held that Shia were not truly Muslims. Nonetheless, its massive popularity in Iran and its overthrow of a pro-American secular monarchy generated enormous enthusiasm among pious Sunni, not just Shia Muslims around the world.[176] Its leader (Ruhollah Khomeini) preached that monarchy was against Islam and America was Islam's enemy, and called for the overthrow of al-Saud family. (In 1987 public address Khomeini declared that "these vile and ungodly Wahhabis are like daggers which have always pierced the heart of the Muslims from the back", and announced that Mecca was in the hands of "a band of heretics".[177])[178] All this spurred Saudi Arabia – a kingdom allied with America – to "redouble their efforts to counter Iran and spread Wahhabism around the world", and reversed any moves by Saudi leaders to distance itself from Wahhabism or "soften" its ideology.[179]

Grand Mosque seizure

In 1979, 400–500 Islamist insurgents, using smuggled weapons and supplies, took over the Grand mosque in Mecca, called for an overthrow of the monarchy, denounced the Wahhabi ulama as royal puppets, and announced the arrival of the Mahdi of "end time". The insurgents deviated from Wahhabi doctrine in significant details,[180] but were also associated with leading Wahhabi ulama (Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz knew the insurgent's leader, Juhayman al-Otaybi).[181] Their seizure of Islam's holiest site, the taking hostage of hundreds of hajj pilgrims, and the deaths of hundreds of militants, security forces and hostages caught in crossfire during the two-week-long retaking of the mosque, all shocked the Islamic world[182] and did not enhance the prestige of Al Saud as "custodians" of the mosque.

The incident also damaged the prestige of the Wahhabi establishment. Saudi leadership sought and received Wahhabi fatawa to approve the military removal of the insurgents and after that to execute them,[183] but Wahhabi clerics also fell under suspicion for involvement with the insurgents.[184] In part as a consequence, Sahwa clerics influenced by Brethren's ideas were given freer rein. Their ideology was also thought more likely to compete with the recent Islamic revolutionism/third-worldism of the Iranian Revolution.[184]

Although the insurgents were motivated by religious puritanism, the incident was not followed by a crackdown on other religious purists, but by giving greater power to the ulama and religious conservatives to more strictly enforce Islamic codes in myriad ways[185] – from the banning of women's images in the media to adding even more hours of Islamic studies in school and giving more power and money to the religious police to enforce conservative rules of behaviour.[186][187][188]

1990 Gulf War

In August 1990 Iraq invaded and annexed Kuwait. Concerned that Saddam Hussein might push south and seize its own oil fields, Saudis requested military support from the US and allowed tens of thousands of US troops to be based in the Kingdom to fight Iraq.[189] But what "amounted to seeking infidels' assistance against a Muslim power" was difficult to justify in terms of Wahhabi doctrine.[190][191]

Again Saudi authorities sought and received a fatwa from leading Wahhabi ulama supporting their action. The fatwa failed to persuade many conservative Muslims and ulama who strongly opposed US presence, including the Muslim Brotherhood-supported Sahwah "Awakening" movement that began pushing for political change in the kingdom.[192] Outside the kingdom, Islamist revival groups that had long received aid from Saudi and had ties with Wahhabis (Arab jihadists, Pakistani and Afghan Islamists) supported Iraq, not Saudi.[193]

During this time and later, many in the Wahhabi/Salafi movement (such as Osama bin Laden) not only no longer looked to the Saudi monarch as an emir of Islam, but supported his overthrow, focusing on jihad against the US and (what they believe are) other enemies of Islam.[194][195] (This movement is sometimes called neo-Wahhabi or neo-salafi.[53][196])

After 9/11

The 2001 9/11 attacks on Saudi's putative ally, the US, that killed almost 3,000 people and caused at least $10 billion in property and infrastructure damage,[197] were assumed by many, at least outside the kingdom, to be "an expression of Wahhabism" since the al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden and most of the 9/11 hijackers were Saudi nationals.[198] A backlash in the formerly hospitable US against the kingdom focused on its official religion that came to be considered by some "a doctrine of terrorism and hate".[86]

Inside the kingdom, Crown Prince Abdullah addressed the country's religious, tribal, business and media leadership following the attacks in a series of televised gatherings calling for a strategy to correct what had gone wrong. According to Robert Lacey, the gatherings and later articles and replies by a top cleric, Abdullah Turki, and two top Al Saud princes, Prince Turki Al-Faisal and Prince Talal bin Abdul Aziz, served as an occasion to sort out who had the ultimate power in the kingdom: not the ulama, but rather the Al Saud dynasty. They declared that Muslim rulers were meant to exercise power, while religious scholars were meant to advise.[199]

In 2003–04, Saudi Arabia saw a wave of al-Qaeda-related suicide bombings, attacks on Non-Muslim foreigners (about 80% of those employed in the Saudi private sector are foreign workers[200] and constitute about 30% of the country's population[201]), and gun battles between Saudi security forces and militants. One reaction to the attacks was a trimming back of the Wahhabi establishment's domination of religion and society. "National Dialogues" were held that included "Shiites, Sufis, liberal reformers, and professional women".[202] In 2009, as part of what some called an effort to "take on the ulama and reform the clerical establishment", King Abdullah issued a decree that only "officially approved" religious scholars would be allowed to issue fatwas in Saudi Arabia. The king also expanded the Council of Senior Scholars (containing officially approved religious scholars) to include scholars from Sunni schools of Islamic jurisprudence other than the Hanbali madhab—Shafi'i, Hanafi and Maliki schools.[203]

Relations with the Muslim Brotherhood have deteriorated steadily. After 9/11, the then interior minister Prince Nayef blamed the Brotherhood for extremism in the kingdom,[204] and he declared it guilty of "betrayal of pledges and ingratitude" and "the source of all problems in the Islamic world", after it was elected to power in Egypt.[205] In March 2014 the Saudi government declared the Brotherhood a "terrorist organization".[189]

In April 2016, Saudi Arabia stripped its religious police, who enforce Islamic law on the society and are known as the Commission for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice, from their power to follow, chase, stop, question, verify identification, or arrest any suspected persons when carrying out duties. They were told to report suspicious behaviour to regular police and anti-drug units, who would decide whether to take the matter further.[206][207]

Muhammad bin Salman

Bold reformist actions on religious policy taken by Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman (MbS) in 2017 have led some to question the future of Wahhabi conservatism. In an October 2017 interview with The Guardian newspaper, MbS stated

What happened in the last 30 years is not Saudi Arabia. What happened in the region in the last 30 years is not the Middle East. After the Iranian revolution in 1979, people wanted to copy this model in different countries, one of them is Saudi Arabia. We didn't know how to deal with it. And the problem spread all over the world. Now is the time to get rid of it.[208]

MbS has ruled in favor of allowing women to drive and enter sport stadiums, eventually reopening cinemas. According to Kamel Daoud, MbS is "above all ... putting pressure on the clergy and announcing the review and certification of the great canons of Muslim orthodoxy, including the hadiths, the collection of the Prophet Muhammad's sayings".[28]

MbS's pronouncements, as well as an international conference on Sunni Islam in Grozny (funded by the government of the United Arab Emirates) where "200 Muslim scholars from Egypt, Russia, Syria, Sudan, Jordan, and Europe reject[ed] Saudi Arabia's doctrine",[209] have been called a "frontal assault on Wahhabism" (as well as an assault on other conservative "interpretations of Islam, such as Salafism and Deobandism").[210][211]

Memoirs of Mr. Hempher

A widely circulated but discredited apocryphal description of the founding of Wahhabism[212][213] known as Memoirs of Mr. Hempher, The British Spy to the Middle East (other titles have been used)[214] alleges that a British agent named Hempher was responsible for the creation of Wahhabism. In the "memoir", Hempher corrupts Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, manipulating him[215] to preach his new interpretation of Islam for the purpose of sowing dissension and disunity among Muslims so that "We, the English people ... may live in welfare and luxury."[214]

Practices

As a religious revivalist movement that works to bring Muslims back from what it believes are foreign accretions that have corrupted Islam,[216] and believes that Islam is a complete way of life and so has prescriptions for all aspects of life, Wahhabism is quite strict in what it considers Islamic behavior. As a result, it has been described as the "strictest form of Sunni Islam".[217] On the other hand, critics argue, Wahhabism is not strict, but a distorted version of Islam and not based on traditional Shari'a law, nor is their practise typical or mired in the roots of Islam.[218][219] Unlike other schools of Sunnism, Wahhabis admonishes to ground Islamic principles solely on the Quran and Hadith,[220] rejecting much material derived within Islamic culture.

This does not mean however, that all adherents agree on what is required or forbidden, or that rules have not varied by area or changed over time. In Saudi Arabia the strict religious atmosphere of Wahhabi doctrine is visible in the conformity in dress, public deportment, and public prayer,[221] and makes its presence felt by the wide freedom of action of the "religious police", clerics in mosques, teachers in schools, and judges (who are religious legal scholars) in Saudi courts.[222]

Commanding right and forbidding wrong

Wahhabism is noted for its policy of "compelling its own followers and other Muslims strictly to observe the religious duties of Islam, such as the five prayers", and for "enforcement of public morals to a degree not found elsewhere".[223] Due to the main interest in purification of Islam, the teaching becomes very repressive to the followers.[224]

While other Muslims might urge abstention from alcohol, modest dress, and salat prayer, for Wahhabis prayer "that is punctual, ritually correct, and communally performed not only is urged but publicly required of men." Not only is wine forbidden, but so are "all intoxicating drinks and other stimulants, including tobacco." Not only is modest dress prescribed, but the type of clothing that should be worn, especially by women (a black abaya, covering all but the eyes and hands) is specified.[72]

Following the preaching and practice of ibn Abd al-Wahhab that coercion should be used to enforce following of sharia, an official committee has been empowered to "Command the Good and Forbid the Evil" (the so-called "religious police")[223][225] in Saudi Arabia – the one country founded with the help of Wahhabi warriors and whose scholars and pious citizens dominate many aspects of the Kingdom's life. Committee "field officers" enforce strict closing of shops at prayer time, segregation of the sexes, prohibition of the sale and consumption of alcohol, driving of motor vehicles by women, and other social restrictions.[226]

A large number of practices have been reported forbidden by Saudi Wahhabi officials, preachers or religious police. Practices that have been forbidden as Bid'a (innovation) or shirk (polytheism) and sometimes "punished by flogging" during Wahhabi history include performing or listening to music, dancing, fortune telling, amulets, television programs (unless religious), smoking, playing backgammon, chess, or cards, drawing human or animal figures, acting in a play or writing fiction (both are considered forms of lying), dissecting cadavers (even in criminal investigations and for the purposes of medical research), recorded music played over telephones on hold or the sending of flowers to friends or relatives who are in the hospital.[120][227][228][229][230][231] Common Muslim practices Wahhabis believe are contrary to Islam include listening to music in praise of Muhammad, praying to God while visiting tombs (including the tomb of Muhammad), celebrating mawlid (birthday of the Prophet),[232] the use of ornamentation on or in mosques, all of which is considered orthodoxy in the rest of the Islamic world.[233] The driving of motor vehicles by women is allowed in every country but Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia[234] and dream interpretation, practiced by the famously strict Taliban, is discouraged by Wahhabis.[235]

Wahhabism emphasizes "Thaqafah Islamiyyah" or Islamic culture and the importance of avoiding non-Islamic cultural practices and non-Muslim friendship no matter how innocent these may appear,[236][237] on the grounds that the Sunna forbids imitating non-Muslims.[238] Foreign practices sometimes punished and sometimes simply condemned by Wahhabi preachers as unIslamic, include celebrating foreign days (such as Valentine's Day [239] or Mothers Day[236][238]) shaving, cutting or trimming of beards,[240] giving of flowers,[241] standing up in honor of someone, celebrating birthdays (including the Prophet's), keeping or petting dogs.[230] Wahhabi scholars have warned against taking non-Muslims as friends, smiling at or wishing them well on their holidays.[68]

Wahhabis are not in unanimous agreement on what is forbidden as sin. Some Wahhabi preachers or activists go further than the official Saudi Arabian Council of Senior Scholars in forbidding (what they believe to be) sin. Several wahhabis have declared football forbidden for a variety of reasons including it is a non-Muslim, foreign practice, because of the revealing uniforms and because of the foreign non-Muslim language used in matches.[242] [243] The Saudi Grand Mufti, on the other hand has declared football permissible (halal). [244]

Senior Wahhabi leaders in Saudi Arabia have determined that Islam forbids the traveling or working outside the home by a woman without their husband's permission – permission which may be revoked at any time – on the grounds that the different physiological structures and biological functions of the two sexes mean that each is assigned a distinctive role to play in the family.[245] As mentioned before, Wahhabism also forbids the driving of motor vehicles by women. Sexual intercourse out of wedlock may be punished with beheading,[246] although sex out of wedlock was permissible with a female slave until the practice of slavery was banned in 1962 (Prince Bandar bin Sultan was the product of "a brief encounter" between his father Prince Sultan bin Abdul Aziz – the Saudi defense minister for many years – and "his slave, a black servingwoman").[247][248]

Despite this strictness, senior Wahhabi scholars of Islam in the Saudi kingdom have made exceptions in ruling on what is haram. Foreign non-Muslim troops are forbidden in Arabia, except when the king needed them to confront Saddam Hussein in 1990; gender mixing of men and women is forbidden, and fraternization with non-Muslims is discouraged, but not at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). Movie theaters and driving by women are forbidden, except at the ARAMCO compound in eastern Saudi, populated by workers for the company that provides almost all the government's revenue. The exceptions made at KAUST are also in effect at ARAMCO.[249]

More general rules of what is permissible have changed over time. Abdulaziz Ibn Saud imposed Wahhabi doctrines and practices "in a progressively gentler form" as his early 20th-century conquests expanded his state into urban areas, especially the Hejab.[250] After vigorous debate Wahhabi religious authorities in Saudi Arabia allowed the use of paper money (in 1951), the abolition of slavery (in 1962), education of females (1964), and use of television (1965).[248] Music, the sound of which once might have led to summary execution, is now commonly heard on Saudi radios. [250] Minarets for mosques and use of funeral markers, which were once forbidden, are now allowed. Prayer attendance, which was once enforced by flogging, is no longer.[251]

Appearance

The uniformity of dress among men and women in Saudi Arabia (compared to other Muslim countries in the Middle East) has been called a "striking example of Wahhabism's outward influence on Saudi society", and an example of the Wahhabi belief that "outward appearances and expressions are directly connected to one's inward state."[233] The "long, white flowing thobe" worn by men of Saudi Arabia has been called the "Wahhabi national dress".[252] Red-and-white checkered or white head scarves known as Ghutrah are worn. In public women are required to wear a black abaya or other black clothing that covers every part of their body other than hands and eyes.

A "badge" of a particularly pious Salafi or Wahhabi man is a robe too short to cover the ankle, an untrimmed beard,[253] and no cord (Agal) to hold the head scarf in place.[254] The warriors of the Ikhwan Wahhabi religious militia wore a white turban in place of an agal.[255]

Wahhabiyya mission

Wahhabi mission, or Dawah Wahhabiyya, is the idea of spreading Wahhabism throughout the world. [256] Tens of billions of dollars have been spent by the Saudi government and charities on mosques, schools, education materials, scholarships, throughout the world to promote Islam and the Wahhabi interpretation of it. Tens of thousands of volunteers[173] and several billion dollars also went in support of the jihad against the atheist communist regime governing Afghanistan.[174]

Regions

Wahhabism originated in the Najd region, and its conservative practices have stronger support there than in regions in the kingdom to the east or west of it.[257][258][259] Glasse credits the softening of some Wahhabi doctrines and practices on the conquest of the Hejaz region "with its more cosmopolitan traditions and the traffic of pilgrims which the new rulers could not afford to alienate".[250]

The only other country "whose native population is Wahhabi and that adheres to the Wahhabi creed", is the small gulf monarchy of Qatar,[260][261] whose version of Wahhabism is notably less strict. Unlike Saudi Arabia, Qatar made significant changes in the 1990s. Women are now allowed to drive and travel independently; non-Muslims are permitted to consume alcohol and pork. The country sponsors a film festival, has "world-class art museums", hosts Al Jazeera news service, will hold the 2022 football World Cup, and has no religious force that polices public morality. Qataris attribute its different interpretation of Islam to the absence of an indigenous clerical class and autonomous bureaucracy (religious affairs authority, endowments, Grand Mufti), the fact that Qatari rulers do not derive their legitimacy from such a class.[261][262]

Views

| Part of a series on Islam Aqidah |

|---|

|

|

Six articles of belief

|

|

Including: 1Al-Ahbash; Barelvis 2Deobandi 3Salafis (Ahl-i Hadith & Wahhabis) 4Sevener-Qarmatians, Assassins & Druzes 5Alawites, Qizilbash & Bektashism; 6Jahmīyya 7Ajardi, Azariqa, Bayhasiyya, Najdat & Sūfrī 8Nukkari; 9Bektashis & Qalandaris; Mevlevis, Süleymancıs & various Ṭarīqah 10Bahshamiyya, Bishriyya & Ikhshîdiyya |

Adherents to the Wahhabi movement identify as Sunni Muslims.[263] The primary Wahhabi doctrine is affirmation of the uniqueness and unity of God (Tawhid),[14][264] and opposition to shirk (violation of tawhid – "the one unforgivable sin", according to Ibn Abd Al-Wahhab).[265] They call for adherence to the beliefs and practices of the salaf (exemplary early Muslims). They strongly oppose what they consider to be heterodox doctrines, particularly those held by the vast majority of Sunnis and Shiites,[266] and practices such as the veneration of Prophets and saints in the Islamic tradition. They emphasize reliance on the literal meaning of the Quran and hadith, rejecting rationalistic theology (kalam). Wahhabism has been associated with the practice of takfir (labeling Muslims who disagree with their doctrines as apostates). Adherents of Wahhabism are favourable to derivation of new legal rulings (ijtihad) so long as it is true to the essence of the Quran, Sunnah and understanding of the salaf, and they do not regard this as bid'ah (innovation) .[267]

Theology

In theology Wahhabism is closely aligned with the Athari (literal) school, which represents the prevalent theological position of the Hanbali school of law.[268][269] Athari theology is characterized by reliance on the zahir (apparent or literal) meaning of the Quran and hadith, and opposition to the rational argumentation in matters of belief favored by Ash'ari and Maturidi theology.[270][271] However, Wahhabism diverges in some points of theology from other Athari movements.[272] These include a zealous tendency toward takfir, which bears a resemblance to the Kharijites.[272][273] Another distinctive feature is a strong opposition to mysticism.[272] Although it is typically attributed to the influence of Ibn Taymiyyah, Jeffry Halverson argues that Ibn Taymiyyah only opposed what he saw as Sufi excesses and never mysticism in itself, being himself a member of the Qadiriyyah Sufi order.[272] DeLong-Bas writes that Ibn Abd al-Wahhab did not denounce Sufism or Sufis as a group, but rather attacked specific practices which he saw as inconsistent with the Quran and hadith.[274]

Ibn Abd al-Wahhab considered some beliefs and practices of the Shia to violate the doctrine of monotheism.[275] According to DeLong-Bas, in his polemic against the "extremist Rafidah sect of Shiis", he criticized them for assigning greater authority to their current leaders than to Muhammad in interpreting the Quran and sharia, and for denying the validity of the consensus of the early Muslim community.[275] He also believed that the Shia doctrine of infallibility of the imams constituted associationism with God.[275]

David Commins describes the "pivotal idea" in Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's teaching as being that "Muslims who disagreed with his definition of monotheism were not ... misguided Muslims, but outside the pale of Islam altogether." This put Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's teaching at odds with that of most Muslims through history who believed that the "shahada" profession of faith ("There is no god but God, Muhammad is his messenger") made one a Muslim, and that shortcomings in that person's behavior and performance of other obligatory rituals rendered them "a sinner", but "not an unbeliever."

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab did not accept that view. He argued that the criterion for one's standing as either a Muslim or an unbeliever was correct worship as an expression of belief in one God ... any act or statement that indicates devotion to a being other than God is to associate another creature with God's power, and that is tantamount to idolatry (shirk). Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab included in the category of such acts popular religious practices that made holy men into intercessors with God. That was the core of the controversy between him and his adversaries, including his own brother.[276]

In Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's major work, a small book called Kitab al-Tawhid, he states that worship in Islam is limited to conventional acts of worship such as the five daily prayers (salat); fasting for Ramadan (Sawm); Dua (supplication); Istia'dha (seeking protection or refuge); Ist'ana (seeking help), and Istigatha to Allah (seeking benefits and calling upon Allah alone). Worship beyond this – making du'a or tawassul – are acts of shirk and in violation of the tenets of Tawhid (monotheism).[277][278]

Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's justification for considering the majority of Muslims of Arabia to be unbelievers, and for waging war on them, can be summed up as his belief that the original pagans the Prophet Muhammad fought "affirmed that God is the creator, the sustainer and the master of all affairs; they gave alms, they performed pilgrimage and they avoided forbidden things from fear of God". What made them pagans whose blood could be shed and wealth plundered was that "they sacrificed animals to other beings; they sought the help of other beings; they swore vows by other beings." Someone who does such things even if their lives are otherwise exemplary is not a Muslim but an unbeliever (as Ibn Abd al-Wahhab believed). Once such people have received the call to "true Islam", understood it and then rejected it, their blood and treasure are forfeit.[279][280]

This disagreement between Wahhabism and Sunni Orthodoxy (adherents of one of the four schools of jurisprudence) over the definition of worship and monotheism has remained much the same since 1740, according to David Commins,[276] although, according to Saudi writer and religious television show host Abdul Aziz Qassim, as of 2014, "there are changes happening within the [Wahhabi] doctrine and among its followers."[49]

According to another source, defining aspects of Wahhabism include a very literal interpretation of the Quran and Sunnah and a tendency to reinforce local practices of the Najd.[281]

Whether the teachings of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab included the need for social renewal and "plans for socio-religious reform of society" in the Arabian Peninsula, rather than simply a return to "ritual correctness and moral purity", is disputed.[282][283]

Jurisprudence (fiqh)

Of the four major sources in Sunni fiqh – the Quran, the Sunna, consensus (ijma), and analogical reasoning (qiyas) – Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's writings emphasized the Quran and Sunna. He used ijma only "in conjunction with its corroboration of the Quran and hadith"[284] (and giving preference to the ijma of Muhammad's companions rather than the ijma of legal specialists after his time), and qiyas only in cases of extreme necessity.[285] He rejected deference to past juridical opinion (taqlid) in favor of independent reasoning (ijtihad), and opposed using local customs.[286] He urged his followers to "return to the primary sources" of Islam in order "to determine how the Quran and Muhammad dealt with specific situations" without considering interpretations of previous Islamic scholarship,[287] when using ijtihad. According to Edward Mortimer, it was imitation of past judicial opinion in the face of clear contradictory evidence from hadith or Qur'anic text that Ibn Abd al-Wahhab condemned.[288] Natana DeLong-Bas writes that the Wahhabi tendency to consider failure to abide by Islamic law as equivalent to apostasy was based on the ideology of Ibn Taymiyya rather than Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's preaching and emerged after the latter's death.[289]

According to an expert on law in Saudi Arabia (Frank Vogel), Ibn Abd al-Wahhab himself "produced no unprecedented opinions". The "Wahhabis' bitter differences with other Muslims were not over fiqh rules at all, but over aqida, or theological positions".[290] Scholar David Cummings also states that early disputes with other Muslims did not center on fiqh, and that the belief that the distinctive character of Wahhabism stems from Hanbali legal thought is a "myth".[291]

Some scholars are ambivalent as to whether Wahhabis belong to the Hanbali legal school. The Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World maintains Wahhabis "rejected all jurisprudence that in their opinion did not adhere strictly to the letter of the Qur'an and the hadith".[292] Cyril Glasse's New Encyclopedia of Islam states that "strictly speaking", Wahhabis "do not see themselves as belonging to any school,"[293] and that in doing so they correspond to the ideal aimed at by Ibn Hanbal, and thus they can be said to be of his 'school'.[294] [295] According to DeLong-Bas, Ibn Abd al-Wahhab never directly claimed to be a Hanbali jurist, warned his followers about the dangers of adhering unquestionably to fiqh, and did not consider "the opinion of any law school to be binding."[296] He did, however, follow the Hanbali methodology of judging everything not explicitly forbidden to be permissible, avoiding the use of analogical reasoning, and taking public interest and justice into consideration.[296]

Loyalty and disassociation

According to various sources—scholars,[43][297][298][299][300][301] former Saudi students, [302] Arabic-speaking/reading teachers who have had access to Saudi text books, [303] and journalists[304] – Ibn 'Abd al Wahhab and his successors preach that theirs is the one true form of Islam. According to a doctrine known as al-wala' wa al-bara' (literally, "loyalty and disassociation"), Abd al-Wahhab argued that it was "imperative for Muslims not to befriend, ally themselves with, or imitate non-Muslims or heretical Muslims", and that this "enmity and hostility of Muslims toward non-Muslims and heretical had to be visible and unequivocal."[305][306] Even as late as 2003, entire pages in Saudi textbooks were devoted to explaining to undergraduates that all forms of Islam except Wahhabism were deviation,[303] although, according to one source (Hamid Algar) Wahhabis have "discreetly concealed" this view from other Muslims outside Saudi Arabia "over the years."[298][307]

In reply, the Saudi Arabian government "has strenuously denied the above allegations", including that "their government exports religious or cultural extremism or supports extremist religious education."[308]

Politics

According to ibn Abdal-Wahhab there are three objectives for Islamic government and society: "to believe in Allah, enjoin good behavior, and forbid wrongdoing." This doctrine has been sustained in missionary literature, sermons, fatwa rulings, and explications of religious doctrine by Wahhabis since the death of ibn Abdal-Wahhab.[72] Ibn Abd al-Wahhab saw a role for the imam, "responsible for religious matters", and the amir, "in charge of political and military issues".[309] (In Saudi history the imam has not been a religious preacher or scholar, but Muhammad ibn Saud[310] and subsequent Saudi rulers.[62][311])

He also taught that the Muslim ruler is owed unquestioned allegiance as a religious obligation from his people so long as he leads the community according to the laws of God. A Muslim must present a bayah, or oath of allegiance, to a Muslim ruler during his lifetime to ensure his redemption after death.[72][312] Any counsel given to a ruler from community leaders or ulama should be private, not through public acts such as petitions, demonstrations, etc. [313] [314] (This strict obedience can become problematic if a dynastic dispute arises and someone rebelling against the ruler succeeds and becomes the ruler, as happened in the late 19th century at the end of the second al-Saud state.[315] Is the successful rebel a ruler to be obeyed, or a usurper?[316])

While this gives the king wide power, respecting shari'a does impose limits, such as giving qadi (Islamic judges) independence. This means not interfering in their deliberations, but also not codifying laws, following precedents or establishing a uniform system of law courts – both of which violate the qadi's independence.[317]

Wahhabis have traditionally given their allegiance to the House of Saud, but a movement of "Salafi jihadis" has developed among those who believe Al Saud has abandoned the laws of God.[194][195] According to Zubair Qamar, while the "standard view" is that "Wahhabis are apolitical and do not oppose the State", there is another "strain" of Wahhabism that "found prominence among a group of Wahhabis after the fall of the second Saudi State in the 1800s", and post 9/11 is associated with Jordanian/Palestinian scholar Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi and "Wahhabi scholars of the 'Shu’aybi' school".[318]

Wahhabis share the belief of Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Islamic dominion over politics and government and the importance of dawah (proselytizing or preaching of Islam) not just towards non-Muslims but towards erroring Muslims. However Wahhabi preachers are conservative and do not deal with concepts such as social justice, anticolonialism, or economic equality, expounded upon by Islamist Muslims.[319] Ibn Abdul Wahhab's original pact promised whoever championed his message, 'will, by means of it, rule and lands and men.'"[22]

Population

One of the more detailed estimates of religious population in the Persian Gulf is by Mehrdad Izady who estimates, "using cultural and not confessional criteria", approximately 4.56 million Wahhabis in the Persian Gulf region, about 4 million from Saudi Arabia, (mostly the Najd), and the rest coming overwhelmingly from the Emirates and Qatar.[24] Most Sunni Qataris are Wahhabis (46.9% of all Qataris)[24] and 44.8% of Emiratis are Wahhabis,[24] 5.7% of Bahrainis are Wahhabis, and 2.2% of Kuwaitis are Wahhabis.[24]

Notable leaders

There has traditionally been a recognized head of the Wahhabi "religious estate", often a member of Al ash-Sheikh (a descendant of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab) or related to another religious head. For example, Abd al-Latif was the son of Abd al-Rahman ibn Hasan.

- Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792) was the founder of the Wahhabi movement.[320][321]

- Abd Allah ibn Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1752–1826) was the head of Wahhabism after his father retired from public life in 1773. After the fall of the first Saudi emirate, Abd Allah went into exile in Cairo where he died.[320]

- Sulayman ibn Abd Allah (1780–1818) was a grandson of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab and author of an influential treatise that restricted travel to and residing in land of idolaters (i.e. land outside of the Wahhabi area).[320]

- Abd al-Rahman ibn Hasan (1780–1869) was head of the religious estate in the second Saudi emirate.[320]

- Abd al-Latif ibn Abd al-Rahman (1810–1876) Head of religious estate in 1860 and early 1870s.[320]

- Abd Allah ibn Abd al-Latif Al ash-Sheikh (1848–1921) was the head of religious estate during period of Rashidi rule and the early years of King Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud.[320]

- Muhammad ibn Ibrahim Al ash-Sheikh (1893–1969) was the head of Wahhabism in mid twentieth century. He has been said to have "dominated the Wahhabi religious estate and enjoyed unrivaled religious authority."[322]

- Ghaliyya al-Wahhabiyya was a female military leader who defended Mecca against recapture by Ottoman forces.

In more recent times, two Wahhabi clerics have risen to prominence with no relation to ibn Abd al-Wahhab.

- Abdul Aziz Bin Baz (1910–1999) has been called "the most prominent proponent" of Wahhabism during his time.[323]

- Muhammad ibn al-Uthaymeen (1925–2001) is another "giant". According to David Dean Commins, no one "has emerged" with the same "degree of authority in the Saudi religious establishment" since their deaths.[323]

International influence and propagation

Explanation for influence

Khaled Abou El Fadl attributed the appeal of Wahhabism to some Muslims as stemming from

- Arab nationalism, which followed the Wahhabi attack on the Ottoman Empire

- Reformism, which followed a return to Salaf (as-Salaf aṣ-Ṣāliḥ);

- Destruction of the Hejaz Khilafa in 1925;

- Control of Mecca and Medina, which gave Wahhabis great influence on Muslim culture and thinking;

- Oil, which after 1975 allowed Wahhabis to promote their interpretations of Islam using billions from oil export revenue.[324]

Scholar Gilles Kepel, agrees that the tripling in the price of oil in the mid-1970s and the progressive takeover of Saudi Aramco in the 1974–1980 period, provided the source of much influence of Wahhabism in the Islamic World.

... the financial clout of Saudi Arabia had been amply demonstrated during the oil embargo against the United States, following the Arab-Israeli war of 1973. This show of international power, along with the nation's astronomical increase in wealth, allowed Saudi Arabia's puritanical, conservative Wahhabite faction to attain a preeminent position of strength in the global expression of Islam. Saudi Arabia's impact on Muslims throughout the world was less visible than that of Khomeini]s Iran, but the effect was deeper and more enduring... it reorganized the religious landscape by promoting those associations and ulamas who followed its lead, and then, by injecting substantial amounts of money into Islamic interests of all sorts, it won over many more converts. Above all, the Saudis raised a new standard – the virtuous Islamic civilization – as foil for the corrupting influence of the West.[81]

Funding factor

Estimates of Saudi spending on religious causes abroad include "upward of $100 billion";[325] between $2 and 3 billion per year since 1975 (compared to the annual Soviet propaganda budget of $1 billion/year);[326] and "at least $87 billion" from 1987 to 2007.[327]

Its largesse funded an estimated "90% of the expenses of the entire faith", throughout the Muslim World, according to journalist Dawood al-Shirian.[328] It extended to young and old, from children's madrasas to high-level scholarship.[329] "Books, scholarships, fellowships, mosques" (for example, "more than 1,500 mosques were built from Saudi public funds over the last 50 years") were paid for.[330] It rewarded journalists and academics, who followed it and built satellite campuses around Egypt for Al Azhar, the oldest and most influential Islamic university.[166] Yahya Birt counts spending on "1,500 mosques, 210 Islamic centres and dozens of Muslim academies and schools".[326][331]

This financial aid has done much to overwhelm less strict local interpretations of Islam, according to observers like Dawood al-Shirian and Lee Kuan Yew,[328] and has caused the Saudi interpretation (sometimes called "petro-Islam"[332]) to be perceived as the correct interpretation—or the "gold standard" of Islam—in many Muslims' minds.[333][334]

Militant and political Islam

According to counter-terrorism scholar Thomas F. Lynch III, Sunni extremists perpetrated about 700 terror attacks killing roughly 7,000 people from 1981 to 2006.[335] What connection, if any, there is between Wahhabism and the Jihadi Salafis such as Al-Qaeda who carried out these attacks, is disputed.

Natana De Long-Bas, senior research assistant at the Prince Alwaleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University, argues:

The militant Islam of Osama bin Laden did not have its origins in the teachings of Ibn Abd-al-Wahhab and was not representative of Wahhabi Islam as it is practiced in contemporary Saudi Arabia, yet for the media it came to define Wahhabi Islam during the later years of bin Laden's lifetime. However "unrepresentative" bin Laden's global jihad was of Islam in general and Wahhabi Islam in particular, its prominence in headline news took Wahhabi Islam across the spectrum from revival and reform to global jihad.[336]

Noah Feldman distinguishes between what he calls the "deeply conservative" Wahhabis and what he calls the "followers of political Islam in the 1980s and 1990s," such as Egyptian Islamic Jihad and later Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. While Saudi Wahhabis were "the largest funders of local Muslim Brotherhood chapters and other hard-line Islamists" during this time, they opposed jihadi resistance to Muslim governments and assassination of Muslim leaders because of their belief that "the decision to wage jihad lay with the ruler, not the individual believer".[337]

Karen Armstrong states that Osama bin Laden, like most extremists, followed the ideology of Sayyid Qutb, not "Wahhabism".[338]

More recently the self-declared "Islamic State" in Iraq and Syria headed by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi has been described as both more violent than al-Qaeda and more closely aligned with Wahhabism.

For their guiding principles, the leaders of the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL, are open and clear about their almost exclusive commitment to the Wahhabi movement of Sunni Islam. The group circulates images of Wahhabi religious textbooks from Saudi Arabia in the schools it controls. Videos from the group's territory have shown Wahhabi texts plastered on the sides of an official missionary van.[339]

According to scholar Bernard Haykel, "for Al Qaeda, violence is a means to an ends; for ISIS, it is an end in itself." Wahhabism is the Islamic State's "closest religious cognate."[339]

Criticism and controversy

Criticism by other Muslims

Among the criticism, or comments made by critics, of the Wahhabi movement are:

- That it is not so much strict and uncompromising as aberrant,[340] going beyond the bounds of Islam in its restricted definition of tawhid (monotheism), and much too willing to commit takfir (declare non-Muslim and subject to execution) Muslims it found in violation of the doctrines of Wahhabism[341] (in the second Wahhabi-Saudi jihad/conquest of the Arabian peninsula, an estimated 400,000 were killed or wounded according to some estimates[118][119][120][121]);

- That bin Saud's agreement to wage jihad to spread Ibn Abdul Wahhab's teachings had more to do with traditional Najd practice of raiding – "instinctive fight for survival and appetite for lucre" – than with religion;[342]

- That it has no connection to other Islamic revival movements;[343]

- That unlike other revivalists, its founder Abd ul-Wahhab showed little scholarship – writing little and making even less commentary;[344]

- That its rejection of the "orthodox" belief in saints, which had become a cardinal doctrine in Sunni Islam very early on,[345][346][347] represents a departure from something which has been an "integral part of Islam ... for over a millennium."[348][349] In this connection, mainstream Sunni scholars also critique the Wahhabi citing of Ibn Taymiyyah as an authority when Ibn Taymiyyah himself adhered to the belief in the existence of saints;[350]

- That its contention towards visiting the tombs and shrines of prophets and saints and the seeking of their intercession, violate tauhid al-'ibada (directing all worship to God alone) has no basis in tradition, in consensus or in hadith, and that even if it did, it would not be grounds for excluding practitioners of ziyara and tawassul from Islam;[341]

- That its use of Ibn Hanbal, Ibn al-Qayyim, and even Ibn Taymiyyah's name to support its stance is inappropriate, as it is historically known that all three of these men revered many aspects of Sufism, save that the latter two critiqued certain practices among the Sufis of their time. Those who criticize this aspect of Wahhabism often refer to the group's use of Ibn Hanbal's name to be a particularly egregious error, arguing that the jurist's love for the relics of Muhammad, for the intercession of the Prophet, and for the Sufis of his time is well established in Islamic tradition;[351]

- That historically Wahhabis have had a suspicious willingness to ally itself with non-Muslim powers (specifically America and Britain), and in particular to ignore the encroachments into Muslim territory of a non-Muslim imperial power (the British) while waging jihad and weakening the Muslim Caliphate of the Ottomans[352][353]

Initial opposition

The first people to oppose Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Wahhab were his father, Abd al-Wahhab and his brother, Salman Ibn Abd al-Wahhab who was an Islamic scholar and qadi. Ibn Abd al-Wahhab's brother wrote a book in refutation of his brother's new teachings, called: "The Final Word from the Qur'an, the Hadith, and the Sayings of the Scholars Concerning the School of Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab", also known as: "Al-Sawa`iq al-Ilahiyya fi Madhhab al-Wahhabiyya" ("The Divine Thunderbolts Concerning the Wahhabi School").[354]

In "The Refutation of Wahhabism in Arabic Sources, 1745–1932",[354] Hamadi Redissi provides original references to the description of Wahhabis as a divisive sect (firqa) and outliers (Kharijites) in communications between Ottomans and Egyptian Khedive Muhammad Ali. Redissi details refutations of Wahhabis by scholars (muftis); among them Ahmed Barakat Tandatawin, who in 1743 describes Wahhabism as ignorance (Jahala).

Shi'a opposition

In 1801 and 1802, the Saudi Wahhabis under Abdul Aziz ibn Muhammad ibn Saud attacked and captured the Shia cities of Karbala and Najaf in Iraq and destroyed the tombs of Husayn ibn Ali, who is the grandson of Muhammad, and Ali (Ali bin Abu Talib), the son-in-law of Muhammad (see: Saudi sponsorship mentioned previously). In 1803 and 1804 the Saudis captured Mecca and Madinah and demolished various tombs of Ahl al-Bayt and Sahabah, ancient monuments, ruins according to Wahhabis, they "removed a number of what were seen as sources or possible gateways to polytheism or shirk" – such as the tomb of Fatimah, the daughter of Muhammad. In 1998 the Saudis bulldozed and poured petroleum over the grave of Aminah bint Wahb, the mother of Muhammad, causing resentment throughout the Muslim World.[355][356][357]