Salafi jihadism

Salafi jihadism or jihadist-Salafism is a transnational religious-political ideology based on a belief in "physical" jihadism and the Salafi movement of returning to what adherents believe to be true Sunni Islam.[1][2]

| Part of a series on:

Salafi movement |

|---|

Sab'u Masajid, Saudi Arabia |

|

Ideology and influences |

|

Founders and key figures |

|

Notable universities |

|

|

|

The terms "Salafist jihadist" and "jihadist-Salafism" were coined by scholar Gilles Kepel in 2002[3][4][5][6] to describe "a hybrid Islamist ideology" developed by international Islamist volunteers in the Afghan anti-Soviet jihad who had become isolated from their national and social class origins.[3] The concept was described by Martin Kramer as an academic term that "will inevitably be [simplified to] jihadism or the jihadist movement in popular usage." (emphasis supplied)[6]

Practitioners are referred to as "Salafi jihadis" or "Salafi jihadists". They are sometimes described as a variety of Salafi,[7] and sometimes as separate from "good Salafis"[5] whose movement eschews any political and organisational allegiances as potentially divisive for the Muslim community and a distraction from the study of religion.[8]

In the 1990s, extremist jihadists of the al-Jama'a al-Islamiyya were active in the attacks on police, government officials and tourists in Egypt, and Armed Islamic Group of Algeria was a principal group in the Algerian Civil War.[3] The most infamous jihadist-Salafist attack is the September 11, 2001 attacks against the United States by al-Qaeda.[9] While Salafism had next-to-no presence in Europe in the 1980s, Salafist jihadists had by the mid-2000s acquired "a burgeoning presence in Europe, having attempted more than 30 terrorist attacks among E.U. countries since 2001."[5] While many see the influence and activities of Salafi jihadists as in decline after 2000 (at least in the United States),[10][11] others see the movement as growing, in the wake of the Arab Spring and the breakdown of state control in Libya and Syria.[12]

History and definition

Gilles Kepel writes that the Salafis whom he encountered in Europe in the 1980s, were "totally apolitical".[3][5] However, by the mid-1990s, he met some who felt jihad in the form of "violence and terrorism" was "justified to realize their political objectives". The combination of Salafi alienation from all things non-Muslim – including "mainstream European society" – and violent jihad created a "volatile mixture".[5] "When you're in the state of such alienation you become easy prey to the jihadi guys who will feed you more savory propaganda than the old propaganda of the Salafists who tell you to pray, fast and who are not taking action".[5]

According to Kepel, Salafist jihadism combined "respect for the sacred texts in their most literal form, ... with an absolute commitment to jihad, whose number-one target had to be America, perceived as the greatest enemy of the faith."[13]

Salafi jihadists distinguished themselves from salafis they term "sheikist", so named because – the jihadists believed – the "sheikists" had forsaken adoration of God for adoration of "the oil sheiks of the Arabian peninsula, with the Al Saud family at their head". Principal among the sheikist scholars was Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz – "the archetypal court ulema [ulama al-balat]". These allegedly "false" salafi "had to be striven against and eliminated", but even more infuriating was the Muslim Brotherhood, who were believed by Salafi jihadists to be excessively moderate and lacking in literal interpretation of holy texts.[13] Iyad El-Baghdadi describes Salafism as "deeply divided" into "mainstream (government-approved, or Islahi) Salafism", and jihadi Salafism.[7]

Another definition of Salafi jihadism, offered by Mohammed M. Hafez, is an "extreme form of Sunni Islamism that rejects democracy and Shia rule". Hafez distinguished them from apolitical and conservative Salafi scholars (such as Muhammad Nasiruddin al-Albani, Muhammad ibn al Uthaymeen, Abd al-Aziz ibn Baz and Abdul-Azeez ibn Abdullaah Aal ash-Shaikh), but also from the sahwa movement associated with Salman al-Ouda or Safar Al-Hawali.[14]

According to Mohammed M. Hafez, contemporary jihadi Salafism is characterized by "five features":

- immense emphasis on the concept of tawhid (unity of God);

- God's sovereignty (hakimiyyat Allah), which defines right and wrong, good and evil, and which supersedes human reasoning is applicable in all places on earth and at all times, and makes unnecessary and un-Islamic other ideologies such as liberalism or humanism;

- the rejection of all innovation (bid‘ah) in Islam;

- the permissibility and necessity of takfir (the declaring of a Muslim to be outside the creed, so that they may face execution);

- and on the centrality of jihad against infidel regimes.[14]

Another researcher, Thomas Hegghammer, has outlined five objectives shared by jihadis:[15]

- Changing the social and political organisation of the state, (an example, being the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) and the former Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC) which fought to overthrow the Algerian state and replace it with an Islamic state.)[15]

- Establishing sovereignty on a territory perceived as occupied or dominated by non-Muslims, (an example being the Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba (Soldiers of the Pure) in Indian-administered Kashmir and the Caucasus Emirate in the Russian Federation).[15]

- Defending the Muslim community (ummah) from external non-Muslim perceived threats, either the "near enemy" (al-adou al-qarib, this includes jihadists Arabs who travelled to Bosnia and Chechnya to defend local Muslims against non-Muslim armies) or the "far enemy" (al-adou al-baid, often affiliates of Al-Qaeda attacking the West).[15]

- Correcting other Muslims' moral behaviour. (In Indonesia, vigilantes first used sticks and stones to attack those they considered "deviant" in behavior before moving on to guns and bombs).[15]

- Intimidating and marginalising other Muslim sects, (an example being Lashkar-e-Jhangvi which has carried out violent attacks on Pakistani Shia for decades, and killings in Iraq.[15])

Robin Wright notes the importance in Salafi jihadist groups of

- the formal process of taking an oath of allegiance (Bay'ah) to a leader.[16] (This can be by individuals to an emir or by a local group to a transglobal group.)

- "marbling", i.e. pretending to cut ties to a less-than-popular global movement when "strategically or financially convenient". (An example is the cutting of ties to al-Qaeda by the Syrian group Al-Nusra Front with al-Qaeda's approval.[16]

According to Michael Horowitz, Salafi jihad is an ideology that identifies the "alleged source of the Muslims' conundrum" in the "persistent attacks and humiliation of Muslims on the part of an anti-Islamic alliance of what it terms 'Crusaders', 'Zionists', and 'apostates'."[17]

Al Jazeera journalist Jamal Al Sharif describes Salafi jihadism as combining "the doctrinal content and approach of Salafism and organisational models from Muslim Brotherhood organisations. Their motto emerged as 'Salafism in doctrine, modernity in confrontation'".[18]

Antecedents of Salafism jihadism include Islamist author Sayyid Qutb, who developed "the intellectual underpinnings" of the ideology. Qutb argued that the world had reached a crisis point and that the Islamic world has been replaced by pagan ignorance of Jahiliyyah.

The group Takfir wal-Hijra, who kidnapped and murdered an Egyptian ex-government minister in 1978, inspired some of "the tactics and methods" used by Al Qaeda.[5]

In Afghanistan the Taliban were of the Deobandi, not Salafi, school of Islam but "cross-fertilized" with bin Laden and other Salafist jihadis.[3]

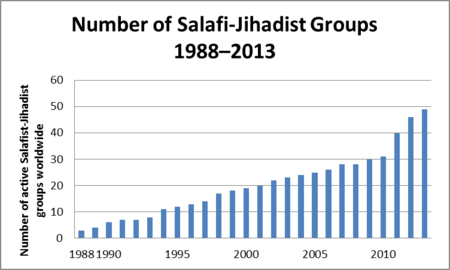

Seth Jones of the Rand Corporation finds in his research that Salafi-jihadist numbers and activity have increased from 2007 to 2013. According to his research:

- the number of Salafi-jihadist groups increased by over 50% from 2010 to 2013, using Libya and parts of Syria as sanctuary.

- the number of Salafi jihadist fighters "more than doubled from 2010 to 2013" using both low and high estimates. The war in Syria was the single most important attraction for Salafi-jihadist fighters.

- attacks by al-Qaeda–affiliated groups (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, al Shabaab, Jabhat al-Nusrah, and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula)

- despite al-Qaeda's traditional focus on the "far enemy" (US and Europe), approximately 99% of the attacks by al-Qaeda and its affiliates in 2013 were against "near enemy" targets (in North Africa, the Middle East, and other regions outside of the West).[12]

Leaders, groups and activities

Leaders and development

"Theoreticians" of Salafist jihadism included Afghan jihad veterans such as the Palestinian Abu Qatada, the Syrian Mustafa Setmariam Nasar, the Egyptian Mustapha Kamel, known as Abu Hamza al-Masri.[19] Osama bin Laden was its most well-known leader. The dissident Saudi preachers Salman al-Ouda and Safar Al-Hawali, were held in high esteem by this school.

Murad al-Shishani of The Jamestown Foundation states there have been three generations of Salafi-jihadists: those waging jihad in Afghanistan, Bosnia and Iraq. As of the mid-2000s, Arab fighters in Iraq were "the latest and most important development of the global Salafi-jihadi movement".[20] These fighters were usually not Iraqis, but volunteers who had come to Iraq from other countries, mainly Saudi Arabia. Unlike in earlier Salafi jihadi actions, Egyptians "are no longer the chief ethnic group".[20] According to Bruce Livesey Salafist jihadists are currently a "burgeoning presence in Europe, having attempted more than 30 terrorist attacks among EU countries" from September 2001 to the beginning of 2005".[5]

According to Mohammed M. Hafez, in Iraq jihadi salafi are pursuing a "system-collapse strategy" whose goal is to install an "Islamic emirate based on Salafi dominance, similar to the Taliban regime in Afghanistan." In addition to occupation/coalition personnel they target mainly Iraqi security forces and Shia civilians, but also "foreign journalists, translators and transport drivers and the economic and physical infrastructure of Iraq."[14]

Groups

Salafist jihadists groups include Al Qaeda,[7] the now defunct Algerian Armed Islamic Group (GIA),[13] and the Egyptian group Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya which still exists.

In the Algerian Civil War 1992–1998, the GIA was one of the two major Islamist armed groups (the other being theArmee Islamique du Salut or AIS) fighting the Algerian army and security forces. The GIA included veterans of the Afghanistan jihad and unlike the more moderate AIS, fought to destabilize the Algerian government with terror attacks designed to "create an atmosphere of general insecurity".[21] It considered jihad in Algeria fard ayn or an obligation for all (adult male sane) Muslims,[21] and sought to "purge" Algeria of "the ungodly" and create an Islamic state. It pursued what Gilles Kepel called a "wholesale massacres of civilians", targeting French-speaking intellectuals, foreigners,[21] and Islamists deemed too moderate, and took a campaign of bombing to France, which supported the Algerian government against the Islamists. Although over 150,000 were killed in the civil war,[22] the GIA eventually lost popular support and was crushed by the security forces.[23] Remnants of the GIA continued on as "Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat", which as of 2015 calls itself al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.[24]

Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, (the Islamic Group) another Salafist-jihadi movement[25] fought an insurgency against the Egyptian government from 1992 to 1998 during which at least 800 Egyptian policemen and soldiers, jihadists, and civilians were killed. Outside of Egypt it is best known for a November 1997 attack at the Temple of Hatshepsut in Luxor where fifty-eight foreign tourists were hacked and shot to death. The group declared a ceasefire in March 1999,[26] although as of 2012 it is still active in jihad against the Bashar al-Assad regime Syria.[25]

Perhaps the most famous and effective Salafist jihadist group was Al-Qaeda.[27] Al-Qaeda evolved from the Maktab al-Khidamat (MAK), or the "Services Office", a Muslim organization founded in 1984 to raise and channel funds and recruit foreign mujahideen for the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan. It was established in Peshawar, Pakistan, by Osama bin Laden and Abdullah Yusuf Azzam. As it became apparent that the jihad had compelled the Soviet military to abandon its mission in Afghanistan, some mujahideen called for the expansion of their operations to include Islamist struggles in other parts of the world, and Al Qaeda was formed by bin Laden on August 11, 1988.[28][29] Members were to making a pledge (bayat) to follow one's superiors.[30] Al-Qaeda emphasized jihad against the "far enemy", i.e. the United States. In 1996, it announced its jihad to expel foreign troops and interests from what they considered Islamic lands, and in 1998, it issued a fatwa calling on Muslims to kill Americans and their allies whenever and wherever they could. Among its most notable acts of violence were the 1998 bombings of US embassies in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi that killed over 200 people;[31] and the 9/11 attacks of 2001 that killed almost 3000 people and caused many billions of dollars in damage.

According to Mohammed M. Hafez, "as of 2006 the two major groups within the jihadi Salafi camp" in Iraq were the Mujahidin Shura Council and the Ansar al Sunna Group.[14] There are also a number of small jihadist Salafist groups in Azerbaijan.[32]

The group leading the Islamist insurgency in Southern Thailand in 2006 by carrying out most of the attacks and cross-border operations,[33] BRN-Koordinasi, favours Salafi ideology. It works in a loosely organized strictly clandestine cell system dependent on hard-line religious leaders for direction.[34][35]

Jund Ansar Allah is, or was, an armed Salafist jihadist organization in the Gaza Strip. On August 14, 2009, the group's spiritual leader, Sheikh Abdel Latif Moussa, announced during Friday sermon the establishment of an Islamic emirate in the Palestinian territories attacking the ruling authority, the Islamist group Hamas, for failing to enforce Sharia law. Hamas forces responded to his sermon by surrounding his Ibn Taymiyyah mosque complex and attacking it. In the fighting that ensued, 24 people (including Sheikh Abdel Latif Moussa himself), were killed and over 130 were wounded.[36]

In 2011, Salafist jihadists were actively involved with protests against King Abdullah II of Jordan,[37] and the kidnapping and killing of Italian peace activist Vittorio Arrigoni in Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip.[38][39]

In the North Caucasus region of Russia, the Caucasus Emirate replaced the nationalism of Muslim Chechnya and Dagestan with a hard-line Salafist-takfiri jihadist ideology. They are immensely focused on upholding the concept of tawhid (purist monotheism), and fiercely reject any practice of shirk, taqlid, ijtihad and bid‘ah. They also believe in the complete separation between the Muslim and the non-Muslim, by propagating Al Wala' Wal Bara' and declaring takfir against any Muslim who (they believe) is a mushrik (polytheist) and does not return to the observance of tawhid and the strict literal interpretation of the Quran and the Sunnah as followed by Muhammad and his companions (Sahaba).[40]

In Syria and Iraq both Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS[41] have been described as Salafist-jihadist. Jabhat al-Nusra has been described as possessing "a hard-line Salafi-Jihadist ideology" and being one of "the most effective" groups fighting the regime.[42] Writing after ISIS victories in Iraq, Hassan Hassan believes ISIS is a reflection of "ideological shakeup of Sunni Islam's traditional Salafism" since the Arab Spring, where salafism, "traditionally inward-looking and loyal to the political establishment", has "steadily, if slowly", been eroded by Salafism-jihadism.[41]

List of groups

According to Seth G. Jones of the Rand Corporation, as of 2014, there were around 50 Salafist-jihadist groups in existence or recently in existence ("present" in the list indicates a group's continued existence as of 2014). (Jones defines Salafi-jihadist groups as those emphasizing the importance of returning to a “pure” Islam, that of the Salaf, the pious ancestors; and those believing that violent jihad is fard ‘ayn (a personal religious duty)).[1]

| Name of Group | Base of Operations | Years |

|---|---|---|

| Abdullah Azzam Brigades (Yusuf al-Uyayri Battalions) |

Saudi Arabia | 2009–present |

| Abdullah Azzam Brigades (Ziyad al-Jarrah Battalions) |

Lebanon | 2009–present |

| Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) | Philippines | 1991–present |

| Aden-Abyan Islamic Army (AAIA) | Yemen | 1994–present |

| Al-Itihaad al-Islamiya (AIAI) | Somalia, Ethiopia | 1994–2002 |

| Al-Qaeda (core) | Pakistan | 1988–present |

| Al-Qaeda in Aceh (a.k.a. Tanzim al Qa’ida Indonesia for Serambi Makkah) |

Indonesia | 2009–2011 |

| Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (Saudi Arabia) | Saudi Arabia | 2002–2008 |

| Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (Yemen) | Yemen | 2008–present |

| al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM, formerly Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat, GSPC) |

Algeria | 1998–present |

| Al Takfir wal al-Hijrah, | Egypt (Sinai Peninsula) | 2011–present |

| Al-Mulathamun (Mokhtar Belmokhtar) | Mali, Libya, Algeria | 2012–2013 |

| Al-Murabitun (Mokhtar Belmokhtar) | Mali, Libya, Algeria | 2013–2017 |

| Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia- Union of Islamic Courts (ARS/UIC) |

Somalia, Eritrea | 2006–2009 |

| Ansar al-Islam | Iraq | 2001–present |

| Ansar al-Sharia (Egypt) | Egypt | 2012–present |

| Ansar al-Sharia (Libya) | Libya | 2012–2017 |

| Ansar al-Sharia (Mali) | Mali | 2012–present |

| Ansar al-Sharia (Tunisia) | Tunisia | 2011–present |

| Ansar Bait al-Maqdis (a.k.a. Ansar Jerusalem) |

Gaza Strip, Egypt (Sinai Peninsula) | 2012–present |

| Ansaru | Nigeria | 2012–present |

| Osbat al-Ansar (AAA) | Lebanon | 1985–present |

| Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF, a.k.a. BIFM) |

Philippines | 2010–present |

| Boko Haram | Nigeria | 2003–present |

| Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (Basayev faction) |

Russia (Chechnya) | 1994–2007 |

| East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM, a.k.a. Turkestan Islamic Party) |

China (Xinjang) | 1989–present |

| Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ) | Egypt | 1978–2001 |

| Harakat Ahrar al-Sham al-Islamiyya | Syria | 2012–present |

| Harakat al-Shabaab al-Mujahideen | Somalia | 2002–present |

| Harakat al-Shuada’a al Islamiyah (a.k.a. Islamic Martyr's Movement, IMM) |

Libya | 1996–2007 |

| Harakat Ansar al-Din | Mali | 2011–2017 |

| Hizbul al Islam | Somalia | 2009–2010 |

| Imarat Kavkaz (IK, or Caucasus Emirate) | Russia (Chechnya) | 2007–present |

| Indian Mujahedeen | India | 2005–present |

| Islamic Jihad Union (a.k.a. Islamic Jihad Group) |

Uzbekistan | 2002–present |

| Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) | Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan | 1997–present |

| Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) | Iraq, Syria | 2004–present |

| Jabhat al-Nusrah | Syria | 2011–present |

| Jaish ul-Adl | Iran | 2013–present |

| Jaish al-Islam (a.k.a. Tawhid and Jihad Brigades) |

Gaza Strip, Egypt (Sinai Peninsula) | 2005–present |

| Jaish al-Ummah (JaU) | Gaza Strip | 2007–present |

| Jamaat Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis | Egypt (Sinai Peninsula) | 2011–present |

| Jamaat Ansarullah (JA) | Tajikistan | 2010–present |

| Jamaah Ansharut Tauhid (JAT) | Indonesia | 2008–present |

| Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) | Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore |

1993–present |

| Jondullah | Pakistan | 2003–present |

| Jund al-Sham | Lebanon, Syria, Gaza Strip, Qatar, Afghanistan |

1999–2008 |

| Khalifa Islamiyah Mindanao (KIM) | Philippines | 2013–present |

| Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT, a.k.a. Mansoorian) | Pakistan (Kashmir) | 1990–present |

| Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) | Libya | 1990–present |

| Liwa al-Islam | Syria | 2011–present |

| Liwa al-Tawhid | Syria | 2012–present |

| Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (GICM) | Morocco, Western Europe | 1998–present |

| Movement for Tawhid and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) |

Mali | 2011–2013 |

| Muhammad Jamal Network (MJN) | Egypt | 2011–present |

| Mujahideen Shura Council | Gaza Strip, Egypt (Sinai Peninsula) | 2011–present |

| Salafia Jihadia (As-Sirat al Moustaquim) | Morocco | 1995–present |

| Suqour al-Sham Brigade | Syria | 2011–2015 |

| Tawhid wal Jihad | Iraq | 1999–2004 |

| Tunisian Combat Group (TCG) | Tunisia, Western Europe | 2000–2011 |

Ruling strategy

In several places and times jihadis have taken control over an area and ruled it as an Islamic state, such as in the case of the ISIL in Syria and Iraq.

As Islamists, establishing uncompromised sharia law is a core value and goal of jihadists, but strategies differed on how quickly this should be done. Observers such as journalist Robert Worth have described jihadis as torn between wanting to build true Islamic order gradually from the bottom up to avoid alienating non-jihadi Muslims (the desire of bin Laden), and not wanting to wait for the Islamic state.[43]

In Zinjibar, Yemen, AQAP established an "emirate" that lasted from May 2011 until the summer of 2012. It emphasized (and publicized with a media campaign) not strict sharia law, but "uncharacteristically gentle" good governance over its conquered territory—rebuilding infrastructure, quashing banditry, and resolving legal disputes.[44] One jihadi veteran of Yemen described its approach towards the local population:

You have to take a gradual approach with them when it comes to religious practices. You can't beat people for drinking alcohol when they don't even know the basics of how to pray. We have to first stop the great sins, and then move gradually to the lesser and lesser ones ... Try to avoid enforcing Islamic punishments as much as possible unless you are forced to do so.[44]

However AQAP's "clemency drained away under the pressure of war",[44] and the area was taken back by the government. The failure of this model (according to New York Times correspondent Robert Worth), may have "taught" jihadis a lesson on the need to instill fear.[44]

The ISIS, is thought to have used for its model a manifesto entitled "The Management of Savagery", which emphasizes the need to create areas of "savagery", i.e. lawlessness, in enemy territory. Once the enemy was too exhausted and weakened from the lawlessness (particularly terrorism) to continue to try and govern, the nucleus of a new caliphate could be established in their absence.[45] The author of "The Management of Savagery", emphasized not so much winning the sympathy of the local Muslims but extreme violence, writing that: "One who previously engaged in jihad knows that it is naught but violence, crudeness, terrorism, frightening [others] and massacring – I am talking about jihad and fighting, not about Islam and one should not confuse them."[45] (Social-media posts from ISIS territory "suggest that individual executions happen more or less continually, and mass executions every few weeks", according journalist Graeme Wood.[46])

Condemnations by Muslims and Challenges

Thousands of Muslim leaders and scholars and dozens of Islamic councils have denounced Salafi jihadism. Some scholars, policy institutes, and political scientists have noted a growing concern that Salafism and Wahhabism can be a gateway to terrorism and violent extremism.[47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57] Notable challenges in countering Salafi jihadism are funding from oil-rich Gulf nations and private donations which are difficult to track,[58][59][60] Saudi efforts to propagate its Wahhabi ideology around the Muslim world,[61] resentment for Western hegemony, authoritarian Arab regimes, feeling defenseless against foreign aggression and that "Muslim blood is cheap,"[62] weak governance, extremist Salafi preaching that counters moderate voices, and other challenges.[63]

References

- Jones, Seth G. (2014). A Persistent Threat: The Evolution of al Qa’ida and Other Salafi Jihadists (PDF). Rand Corporation. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- Moghadam, Assaf (2008). The Globalization of Martyrdom: Al Qaeda, Salafi Jihad, and the Diffusion of ... JHU Press. pp. 37–8. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- "Jihadist-Salafism" is introduced by Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2002)

- Deneoux, Guilain (June 2002). "The Forgotten Swamp: Navigating Political Islam". Middle East Policy. pp. 69–71."

- "The Salafist movement by Bruce Livesey". PBS Frontline. 2005. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Kramer, Martin (Spring 2003). "Coming to Terms: Fundamentalists or Islamists?". Middle East Quarterly. X (2): 65–77. Archived from the original on 2015-01-01. Retrieved 2015-01-01.

French academics have put the term into academic circulation as 'jihadist-Salafism.' The qualifier of Salafism – an historical reference to the precursor of these movements – will inevitably be stripped away in popular usage.

- El-Baghdadi, Iyad. "Salafis, Jihadis, Takfiris: Demystifying Militant Islamism in Syria". 15 January 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- "Indonesia: Why Salafism and Terrorism Mostly Don't Mix". International Crisis Group. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- "The Global Salafi Jihad". the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. July 9, 2003. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- Sageman, Marc (April 30, 2013). "The Stagnation of Research on Terrorism". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on September 22, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2015.

al Qaeda is no longer seen as an existential threat to the West ... the hysteria over a global conspiracy against the West has faded.

- Mearsheimer, John J. (January–February 2014). "America Unhinged" (PDF). National Interest: 9–30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

Terrorism – most of it arising from domestic groups – was a much bigger problem in the United States during the 1970s than it has been since the Twin Towers were toppled.

- Jones, Seth G. (2014). A Persistent Threat: The Evolution of al Qa’ida and Other Salafi Jihadists (PDF). Rand Corporation. pp. ix–xiii. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- Jihad By Gilles Kepel, Anthony F. Roberts. Archived from the original on 14 June 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Suicide Bombers in Iraq By Mohammed M. Hafez. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Hegghammer, Thomas (2009). "10. Jihadi-Salafis or Revolutionaries? On Religion and Politics in the Study of Militant Islamismf". In Meijer, R. (ed.). Global Salafism: Islam's New Religious Movement (PDF). Columbia University Press. pp. 244–266. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Wright, Robin (December 12, 2016). "AFTER THE ISLAMIC STATE". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- Horowitz, Michael. "Defining and confronting the Salafi Jihad". 11 Feb 2008. Middle East Strategy at Harvard. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- Al Sharif, Jamal. "Salafis in Sudan:Non-Interference or Confrontation". 03 July 2012. AlJazeera Center for Studies. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- "Jihadist-Salafism" is introduced by Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2002), p. 220

- "The Rise and Fall of Arab Fighters in Chechnya" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- "Jihadist-Salafism" is introduced by Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2002), pp. 260–62

- "Algeria country profile – Overview". BBC. 24 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- Gilles Kepel, Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2002), pp. 260–75

- "Islamism, Violence and Reform in Algeria: Turning the Page (Islamism in North Africa III)]". International Crisis Group Report. 30 July 2004. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "Former militants of Egypt's Al-Gama'a al-Islamiya struggle for political success" (PDF). Terrorism Monitor (Jamestown Foundation). X (18): 1. September 27, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- "al-Gama'at al-Islamiyya Jama'a Islamia (Islamic Group, IG)". FAS Intelligence Resource Program. Archived from the original on 20 April 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- Jones, Seth G. (2014). A Persistent Threat: The Evolution of al Qa’ida and Other Salafi Jihadists (PDF). Rand Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- Wander, Andrew (July 13, 2008). "A history of terror: Al-Qaeda 1988–2008". The Guardian, The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

11 August 1988 Al-Qaeda is formed at a meeting attended by Bin Laden, Zawahiri and Dr Fadl in Peshawar, Pakistan.

- "The Osama bin Laden I know". January 18, 2006. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- Wright 2006, pp. 133–34.

- Bennett, Brian (12 June 2011). "Al Qaeda operative key to 1998 U.S. embassy bombings killed in Somalia". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- The Two Faces of Salafism in Azerbaijan Archived 2010-12-26 at the Wayback Machine. Terrorism Focus Volume: 4 Issue: 40, December 7, 2007, by: Anar Valiyev

- "A Breakdown of Southern Thailand's Insurgent Groups". Terrorism Monitor. The Jamestown Foundation. 4 (17). September 8, 2006. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Rohan Gunaratna & Arabinda Acharya , The Terrorist Threat from Thailand: Jihad Or Quest for Justice?

- Zachary Abuza, The Ongoing Insurgency in Southern Thailand, INSS, p. 20

- Al-Quds Al-Arabi (London), August 19, 2009.

- "Jordan protests: Rise of the Salafist Jihadist movement". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 July 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- "Body of Italian found in Gaza Strip house-Hamas". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 September 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- "Italian peace activist killed in Gaza". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Darion Rhodes, Salafist-Takfiri Jihadism: the Ideology of the Caucasus Emirate Archived 2014-09-03 at the Wayback Machine, International Institute for Counter-Terrorism, March 2014

- Hassan, Hassan (16 August 2014). "Isis: a portrait of the menace that is sweeping my homeland". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Benotman, Noman. "Jabhat al-Nusra, A Strategic Briefing" (PDF). circa 2012. Quilliam Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- Worth, Robert F. (2016). A Rage for Order: The Middle East in Turmoil, from Tahrir Square to ISIS. Pan Macmillan. pp. 172–3. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Worth, Robert F. (2016). A Rage for Order: The Middle East in Turmoil, from Tahrir Square to ISIS. Pan Macmillan. p. 173. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Worth, Robert F. (2016). A Rage for Order: The Middle East in Turmoil, from Tahrir Square to ISIS. Pan Macmillan. pp. 173–4. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- Wood, Graeme (March 2015). "What ISIS Really Wants". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- "PURITAN POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT: THE EVOLUTION OF SALAFISM IN MALAYSIA". www.understandingconflict.org. Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Meleagrou-Hitchens, Alexander. "Salafism in America" (PDF). George Washington University. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Shadi Hamid and Rashid Dar (2016). "Islamism, Salafism, and jihadism: A primer". Brookings. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Cohen, Eyal. "PUSHING THE JIHADIST GENIE BACK INTO THE BOTTLE" (PDF). Brookings. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Prominent scholars declare ISIS caliphate 'null and void'". Middle East Monitor. 5 July 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Muslims Against ISIS Part 1: Clerics & Scholars | Wilson Center". www.wilsoncenter.org. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Letter to Baghdadi". Open Letter to Baghdadi. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Yaʻqūbī (Shaykh.), Muḥammad (2015). Refuting ISIS: Destroying Its Religious Foundations and Proving that it Has Strayed from Islam and that Fighting it is an Obligation. Sacred Knowledge. ISBN 978-1-908224-12-5. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Castillo, Hamza. "The Kingdom's Failed Marriage" (PDF). Halaqa. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Lynch, Marc (17 May 2010). "Islam Divided Between Salafi-jihad and the Ikhwan". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 33 (6): 467–487. doi:10.1080/10576101003752622. ISSN 1057-610X. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "The Salafi-Jihad as a Religious Ideology". Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. 15 February 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Dubai, Maria Abi-Habib in Beirut and Rory Jones in (28 June 2015). "Kuwait Attack Renews Scrutiny of Terror Support Within Gulf States". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Saudi Funding of ISIS". www.washingtoninstitute.org. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Byman, Daniel L. (May 2016). "The U.S.-Saudi Arabia counterterrorism relationship". Brookings. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Wehrey, Frederic; Boukhars, Anouar (2019). Salafism in the Maghreb: Politics, Piety, and Militancy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-094240-3. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Arab and Muslim blood is cheap". Middle East Monitor. 16 February 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Estelle, Emily. "The Challenge of North African Salafism". Critical Threats. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

Further reading

- Oliver, Haneef James. "Sacred Freedom: Western Liberalist Ideologies In The Light of Islam". TROID, 2006, ISBN 0-9776996-0-9 (Free)

- Global jihadism: theory and practice, Brachman, Jarret, Taylor & Francis, 2008, ISBN 0-415-45241-4, ISBN 978-0-415-45241-0

- Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. Harvard University Press.