Uralo-Siberian languages

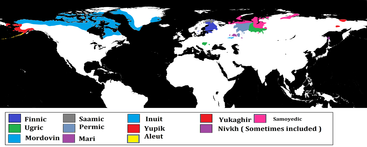

Uralo-Siberian is a hypothetical language family consisting of Uralic, Yukaghir, Eskimo–Aleut, possibly Nivkh and formerly Chukotko-Kamchatkan. It was proposed in 1998 by Michael Fortescue, an expert in Eskimo–Aleut and Chukotko-Kamchatkan, in his book Language Relations across Bering Strait. In 2011, Fortescue removed Chukotko-Kamchatkan from the proposal.[1]

| Uralo-Siberian | |

|---|---|

| (hypothetical) | |

| Geographic distribution | Northern Eurasia, the Arctic |

| Linguistic classification | Proposed language family |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | None |

History

Structural similarities between Uralic and Eskimo–Aleut languages were observed early. In 1746, the Danish theologian Marcus Wöldike compared Greenlandic to Hungarian. In 1818, Rasmus Rask considered Greenlandic to be related to the Uralic languages, Finnish in particular, and presented a list of lexical correspondences (Rask also considered Uralic and Altaic to be related to each other.) In 1959, Knut Bergsland published the paper The Eskimo–Uralic Hypothesis, in which he, like other authors before him, presented a number of grammatical similarities and a small number of lexical correspondences. In 1962, Morris Swadesh proposed a relationship between the Eskimo–Aleut and Chukotko-Kamchatkan language families. In 1998, Michael Fortescue presented more detailed arguments in his book, Language Relations across Bering Strait. His title evokes Morris Swadesh's 1962 article, "Linguistic relations across the Bering Strait".

Michael Fortescue (2017) presents, besides new linguistic evidence, also several genetic studies, that support a common origin of the included groups, with a suggested homeland in Northeast Asia.[2]

Typology

Fortescue (1998, pp. 60–95) surveys 44 typological markers and argues that a typological profile uniquely identifying the language families proposed to comprise the Uralo-Siberian family can be established. The Uralo-Siberian hypothesis is rooted in the assumption that this distinct typological profile was, rather than an areal profile common to four unrelated language families, the profile of a single language ancestral to all four: Proto-Uralo-Siberian.

- Phonology

- A single, voiceless series of stop consonants.

- Voiced stops such as /d/ occur in the Indo-European, Yeniseian, Turkic, Mongolian, Tungusic, Japonic and Sino-Tibetan languages. They have also later arisen in several branches of Uralic.

- Aspirated stops such as /tʰ/ occur in Korean, Nivkh, Na-Dene, Haida, etc.

- Ejective stops such as /tʼ/ occur in Na-Dene, Haida, Salishan, Tsimshian, etc.

- A series of voiced non-sibilant fricatives, including /ð/, which lack voiceless counterparts such as /θ/.

- Original non-sibilant fricatives are absent from most other languages of Eurasia. Voiceless fricatives prevail over voiced ones in most of northern America. Both voiced and voiceless fricatives occur in Nivkh.

- Primary palatal or palatalized consonants such as /ɲ ~ nʲ/, /ʎ ~ lʲ/.

- The occurrence of a rhotic consonant /r/.

- Found in most other language families of northern Eurasia as well; however, widely absent from languages of northern America.

- Consonant clusters are absent word-initially and word-finally, but present word-medially.

- A feature shared with most 'Altaic' languages. Contrasts with the presence of abundant consonant clusters in Nivkh, as well as in the Indo-European and Salishan languages.

- Canonically bisyllabic word roots, with the exception of pronouns.

- Contrasts with canonically monosyllabic word roots in Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan, Yeniseian, Na-Dene, Haida, Tsimshian, Wakashan, Salishan, etc. Some secondarily monosyllabic word roots have developed in Aleut and multiple Uralic languages, and they predominate in Itelmen.

- Word-initial stress.

- Morphology

- Exclusively suffixal morphology.

- Contrasts particularly with Yeniseian and Na-Dene.

- Accusative case, genitive case and at least three local cases.

- singular, plural and dual number.

- The absence of adjectives and adverbs as morphologically distinct parts of speech.

- Evidentiality marking.

- Indicative markers based on participles.

- Possessive suffixes.

- Syntax

- The presence of a copula, used as an auxiliary verb.

- Negation expressed by an auxiliary verb (known as a negative verb)

- Subordinate clauses based on non-finite verb forms.

None of the four families shows all of these 17 features; ranging from 12 reconstructible in Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan to 16 in Proto-Uralic. Frequently the modern-day descendant languages have diverged further from this profile — particularly Itelmen, for which Fortescue assumes substrate influence from a language typologically more alike to the non-Uralo-Siberian languages of the region.

Several more widely spread typologically significant features may also instead represent contact influence, according to Fortescue (1998):

- Primary uvular consonants are absent from Uralic, but can be found in Chukotko-Kamchatkan and Eskimo-Aleut. They are also present in Yukaghir, though are likely to be of secondary origin there (as also in the Uralic Selkup, as well as a large number of Turkic languages). They are, however, firmly entrenched in the non-Uralo-Siberian languages of northernmost Eurasia, including Yeniseian, Nivkh, Na-Dene, Haida, Salishan, etc. Fortescue suggests that the presence of uvulars in CK and EA may, then, represent an ancient areal innovation acquired from the earlier, "pre-Na-Dene" languages of Beringia.

Evidence

Morphology

Apparently shared elements of Uralo-Siberian morphology include the following:

| *-t | plural |

| *-k | dual |

| *m- | 1st person |

| *t- | 2nd person |

| *ka | interrogative pronoun |

| *-n | genitive case |

Proponents of the Nostratic hypothesis consider these apparent correspondences to be evidence in support of the proposed larger Nostratic family.

Lexicon

Fortescue (1998) lists 94 lexical correspondence sets with reflexes in at least three of the four language families, and even more shared by two of the language families. Examples are *ap(p)a 'grandfather', *kað'a 'mountain' and many others.

Below are some lexical items reconstructed to Proto-Uralo-Siberian, along with their reflexes in Proto-Uralic, Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan (sometimes Proto-Chukchi), and Proto-Eskimo–Aleut (sometimes Proto-Eskimo or Aleut). (Source: Fortescue 1998:152–158.)

| Proto-Uralo-Siberian | Proto-Uralic | Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan | Proto-Eskimo–Aleut |

| aj(aɣ)- 'push forward' | aja- 'drive, chase' | aj-tat- 'chase, herd' (PC) | ajaɣ- 'push, thrust at with pole' |

| ap(p)a 'grandfather' | appe 'father in law' | æpæ 'grandfather' | ap(p)a 'grandfather' |

| el(l)ä 'not' | elä 'not' | ællæ 'not' (PC) | -la(ɣ)- 'not' (A) |

| pit(uɣ)- 'tie up' | pitV- 'tie' (FU) | pət- 'tie up' | pətuɣ- 'tie up' |

| toɣə- 'take' | toɣe- 'bring, take, give' (FU) | teɣiŋrə- 'pull out' | teɣu- 'take' (PE) |

Regular sound correspondences

These sound correspondences with Yukaghir were suggested in Fortescue 1998:[3]

| Yukaghir | Proto-Eskimo-Aleut |

|---|---|

| *l/l’ | Ø-/-l- |

| *-nt | -t-/-n |

| *-nc’- | -t- |

| *-ŋk- | -k- |

| *-mp- | -p- |

| *w | Ø-/-v- |

| *j | Ø-/-y- |

| *-ɣ- | -ɣ-/-R- (and -k-/-q-) |

| *-r- | -l/ð- |

Yukaghir and Uralic:[4]

| Uralic | Yukaghir |

|---|---|

| kk | k |

| tt | t/δ |

| pp | p |

| mp | pp |

| Uralic | EA[5][6][7] |

|---|---|

| s | Ø |

| a | sa |

| l | t |

| m | m |

| x | v |

| s | Ø |

| d | ð |

| k | ɣ |

| t | c |

| j | y/i |

| n | ŋ |

| tä | ci |

| ti | cai |

| ü | u |

Vocabulary[3][8]

| Proto-Yukagir | Proto-Eskimo-Aleut |

|---|---|

| aka 'elder brother' | akkak 'uncle' |

| al 'below' | atə 'below' |

| amlə 'swallow' | ama 'suckle' |

| aŋa 'mouth' | aŋ-va- 'open' |

| carqə- 'bent' | caqə- 'turn, move away' |

| cowinə 'spear' | caviɣ 'knife' |

| kin 'who' | kina 'who' |

| ləɣ- 'eat' | iɣa- 'swallow' |

| mel 'breast' | məluɣ 'breast' |

| qar 'skin' 'cover' | qaðə 'surface of something' |

| um 'close' | uməɣ 'close' |

| n’ə 'get' | nəɣ 'get' |

| para 'origin' | paðə 'opening' |

| ta 'that' | ta 'that' |

| Uralic | Eskimo-Aleu[9]t[7] |

|---|---|

| ila 'under' | at(ǝ) 'down |

| elä 'live' | ǝt(ǝ) 'be' |

| tuli 'come' | tut 'arrive,land' |

| kuda 'morning, dawn' | qilaɣ 'sky' |

| ke | kina |

| to | ta |

| kuda 'weave' | qilaɣ 'weave' |

The meanings 'weave' and 'morning' are most likely unrelated, which means that these are instances of coincidental homonymy, which only very rarely happens by chance, which means that some kind of contact most likely happened, but exact conclusions cannot be drawn with modern information.[7]

| Proto-Uralic | Proto-Yukaghir |

|---|---|

| käliw 'sibling-in-law' | käli |

| wanča 'root' | wanča |

| iś/ća 'father' | iśa |

| lunta 'bird' | lunta |

| toxi- 'to bring' | toxi |

| ela 'under' | ola |

Proto-Uralic and Proto-Eskimo-Aleut number and case markers[6]

| Proto-Uralic | Proto-Eskimo-Aleut | |

|---|---|---|

| nom./absolute sing | Ø | Ø |

| Dual | -kə | k |

| Plural | -t | -t |

| locative | -(kə)na | -ni |

| accusative sing | -m | - |

| plural accusative | -j/i | -(ŋ)i |

| ablative | -(kə)tə | -kənc |

| dative/lative | -kə/-ŋ | -ŋun |

Yukaghir and Proto-Eskimo-Aleut Verbal and nominal inflections[3]

| Yukaghir | Eskimo-Aleut | |

|---|---|---|

| trans. 1s | ŋ | ŋa |

| 3pl | ŋi | ŋi |

| 3 poss. | ntə | n |

| vialis | *-(n)kən | *-(n)kən |

| Abl | *-(n)kət | m/n)əɣ |

| all | (ŋi)n’ | -(m/n)un / ŋus/-ŋun |

| adv. loc./lative | nə | nə |

Possessive suffixes[10]

| Samoyedic | Eskimo-Aleut | |

|---|---|---|

| 1sg | mǝ | m(ka) |

| 2sg | tǝ | t |

| 3sg | sa | sa |

| 1pl | mat | mǝt |

| 2pl | tat | tǝt |

| 3pl | iton | sat |

Nenets accusative and Eskimo relative possessive affixes[6]

| 1sg | 2sg | 4sg | 1pl | 2pl | 4pl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ma | vət/mət | mi | mta | vci/mci | məŋ |

| sg1 | 2sg | 3sg | 1pl | 2pl | 3pl |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m'i/mə | mtə | mtab | waq/mat | mtaq/mtat | mtoh/mton |

Urheimat

Fortescue argues that the Uralo-Siberian proto-language (or a complex of related proto-languages) may have been spoken by Mesolithic hunting and fishing people in south-central Siberia (roughly, from the upper Yenisei river to Lake Baikal) between 8000 and 6000 BC, and that the proto-languages of the derived families may have been carried northward out of this homeland in several successive waves down to about 4000 BC, leaving the Samoyedic branch of Uralic in occupation of the Urheimat thereafter.

Relationships

Some or all of the four Uralo-Siberian families have been included in more extensive groupings of languages (see links below). Fortescue's hypothesis does not oppose or exclude these various proposals. In particular, he considers that a remote relationship between Uralo-Siberian and Altaic (or some part of Altaic) is likely (see Ural–Altaic languages). However, Fortescue holds that Uralo-Siberian lies within the bounds of the provable, whereas Nostratic may be too remote a grouping to ever be convincingly demonstrated.

The University of Leiden linguist Frederik Kortlandt (2006:1) asserts that Indo-Uralic (a proposed language family consisting of Uralic and Indo-European) is itself a branch of Uralo-Siberian and that, furthermore, the Nivkh language also belongs to Uralo-Siberian. This would make Uralo-Siberian the proto-language of a much vaster language family. Kortlandt (2006:3) considers that Uralo-Siberian and Altaic (defined by him as consisting of Turkic, Mongolian, Tungusic, Korean, and Japanese) may be coordinate branches of the Eurasiatic language family proposed by Joseph Greenberg but rejected by most linguists.

Bibliography

Works cited

- Bergsland, Knut (1959). "The Eskimo–Uralic hypothesis". Journal de la Societé finno-ougrienne. 61: 1–29.

- Fortescue, Michael. 1998. Language Relations across Bering Strait: Reappraising the Archaeological and Linguistic Evidence. London and New York: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-70330-3.

- Kortlandt, Frederik. 2006. "Indo-Uralic and Altaic".

- Swadesh, Morris (1962). "Linguistic relations across the Bering Strait". American Anthropologist. 64: 1262–1291. doi:10.1525/aa.1962.64.6.02a00090.

References

- Fortescue, Michael (2011). "The relationship of Nivkh to Chukotko-Kamchatkan revisited". Lingua. 121 (8): 1359–1376. doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2011.03.001.

I would no longer wish to relate CK directly to [Uralo-Siberian], although I believe that some of the lexical evidence [...] will hold up in terms of borrowing/diffusion.

- "(PDF) Correlating Palaeo-Siberian languages and populations: recent advances in the Uralo-Siberian hypothesis". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-03-22.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320126371_Correlating_Palaeo-Siberian_languages_and_populations_recent_advances_in_the_Uralo-Siberian_hypothesis

- https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e2e6/c23bc4aa6586d6f0c0075ff145666ce9a53c.pdf

- https://www.academia.edu/42632305/Uralic-Eskimo_initial_first_vowel_and_medial_consonant_correspondences_with_100_lexical_examples

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308045130_How_the_accusative_became_the_relative_A_Samoyedic_key_to_the_Eskimo-Uralic_relationship

- Kloekhorst, Alwin; Pronk, Tijmen (2019-09-25), "Introduction: Reconstructing Proto-Indo-Anatolian and Proto-Indo-Uralic", The Precursors of Proto-Indo-European, Brill | Rodopi, pp. 1–14, ISBN 978-90-04-40935-4, retrieved 2020-06-22

- http://www.elisanet.fi/alkupera/UralicYukaghirWordlist.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=81sE6cAUnpI&lc=UgzR2Wj9sYIlcPWFZHx4AaABAg

- Bonnerjea, René (January 1978). "A Comparison between Eskimo-Aleut and Uralo-Altaic Demonstrative Elements, Numerals, and Other Related Semantic Problems". International Journal of American Linguistics. 44 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1086/465517. ISSN 0020-7071.

Further reading

- Blažek, Václav. 2006. "Chukcho-Kamchatkan and Uralic: lexical evidence of their genetic relationship". In: Orientalia et Classica XI. Aspects of Comparativistics 2, pp. 197–212. Moscow.

- Georg, Stefan; Seefloth, Uwe 2020. "Uralo-Eskimo?".

- Greenberg, Joseph H (2000). "Review of Michael Fortescue, Language Relations across Bering Strait: Reappraising the Archaeological and Linguistic Evidence.". Review of Archaeology. 21 (2): 23–24.

- Künnap, A. 1999. Indo-European-Uralic-Siberian Linguistic and Cultural Contacts. Tartu, Estonia: University of Tartu, Division of Uralic Languages.

- Seefloth, Uwe (2000). "Die Entstehung polypersonaler Paradigmen im Uralo-Sibirischen". Zentralasiatische Studien. 30: 163–191.

See also

- Proto-Chukotko-Kamchatkan language

- Proto-Uralic language

- Classification schemes for indigenous languages of the Americas

- Linguistic areas of the Americas

Related language family proposals

External links

- Linguist List post about Uralo-Eskimo grammar as reconstructed by Uwe Seefloth, who finds Uralic and Eskimo–Aleut to be each other's closest relatives within Uralo-Siberian

- Discussion of the above and comparisons to Indo-European

- More discussion of the above

- "Nivkh as a Uralo-Siberian language" by Frederik Kortlandt (2004)

- "Chukcho-Kamchatkan and Uralic: Evidence of their genetic relationship" by Václav Blažek (2006)