U-matic

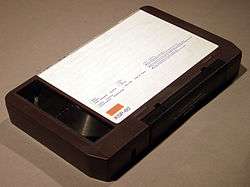

U-matic is an analogue recording videocassette format first shown by Sony in prototype in October 1969, and introduced to the market in September 1971. It was among the first video formats to contain the videotape inside a cassette, as opposed to the various reel-to-reel or open-reel formats of the time. The videotape is 3⁄4 in (19 mm) wide, so the format is often known as "three-quarter-inch" or simply "three-quarter", compared to open reel videotape formats in use, such as 1 in (25 mm) type C videotape and 2 in (51 mm) quadruplex videotape.

| |

Sony U-matic VTR BVU-800 | |

| Media type | Magnetic Tape |

|---|---|

| Encoding | NTSC, PAL, SECAM |

| Developed by | Sony |

| Usage | Video production |

Unlike most other cassette-based tape formats, the supply and take-up reels in the cassette turn in opposite directions during playback, fast-forward, and rewind: one reel would run clockwise while the other would run counter-clockwise. A locking mechanism integral to each cassette case secures the tape hubs during transportation to keep the tape wound tightly on the hubs. Once the cassette is taken off the case, the hubs are free to spin. A spring-loaded tape cover door protects the tape from damage; when the cassette is inserted into the VCR, the door is released and is opened, enabling the VCR mechanism to spool the tape around the spinning video drum. Accidental recording is prevented by the absence of a red plastic button fitted to a hole on the bottom surface of the tape; removal of the button disabled recording.

Development

As part of its development, in March 1970, Sony, Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. (Panasonic), Victor Co. of Japan (JVC), and five non-Japanese companies reached agreement on unified standards.

The first generation of U-matic VCRs are large devices, approximately 30 in (76 cm) wide, 24 in (61 cm) deep, and 12 in (30 cm) high, requiring special shelving, and had mechanical controls limited to Record, Play, Rewind, Fast-Forward, Stop and Pause (with muted video on early models). Later models sported improvements such as chassis sized for EIA 19-inch rack mounting, with sliding rack rails for compressed storage in broadcast environments, solenoid control mechanics, jog-shuttle knob, remote controls, Vertical Interval Time Code (VITC), longitudinal time code, internal cuts-only editing controls, "Slo-Mo" slow-motion playback, and Dolby audio noise reduction.

U-matic was named after the shape of the tape path when it was threaded around the helical scan video head drum, which resembles the letter U.[1] Betamax uses a similar type of "B-load" as well. Recording time is limited to one hour.

Introduction

At the 1971 introduction of U-Matic, Sony originally intended it to be a videocassette format oriented at the consumer market. This proved to be something of a failure, because of the high manufacturing cost and resulting retail price of the format's first VCRs.[2] But the cost was affordable enough for industrial and institutional customers, where the format was very successful for such applications as business communication and educational television. As a result, Sony shifted U-Matic's marketing to the industrial, professional, and educational sectors.

U-Matic saw even more success from the television broadcast industry in the mid-1970s, when a number of local TV stations and national TV networks used the format when its first portable model, the Sony VO-3800, was released in 1974. This model ushered in the era of ENG, or electronic news gathering, which eventually made obsolete the previous 16mm film cameras normally used for on-location television news gathering. Film required developing which took time, compared to the instantly available playback of videotape, making faster breaking news possible.

Models

U-matic is also available in a smaller cassette size, officially known as U-Matic S. Much like VHS-C, U-Matic S was developed as a more portable version of U-Matic, to be used in smaller-sized S-format recorders such as the aforementioned Sony VO-3800, as well as the later VO-4800, VO-6800, VO-8800, BVU-50, BVU-100 and BVU-150 models from Sony, among others from Sony, Panasonic, JVC and other manufacturers. To minimise weight and bulk in the field, portable recorders had an external AC power supply, or could be operated from rechargeable nickel-cadmium batteries.

The price point of the VO series was oriented toward educational, corporate and industrial fields, featured unbalanced audio connectors, and did not typically include SMPTE time code (although one or two companies offered after-market modification services to install longitudinal time code). The VO-3800 was largely metal, which made the unit heavy, but still technically portable. The VO-4800 had the same functionality as the VO-3800, but at a greatly reduced weight and size, by replacing many components with plastic. The VO-6800 added the improvement of a long, thin battery standard ("candy bars") that permitted storage of the batteries in a trouser pocket. Common model numbers for these batteries were NP-1, NP-1A and NP-1B. The VO-8800 was the last of the portable VO series to be produced by Sony, and featured solenoid-controlled transport.

The Sony BVU series added longitudinal and vertical interval SMPTE time code, balanced audio XLR connectors, and heavier-duty transport features. The BVU-50 enabled recording in the field but not playback, and the BVU-100 permitted both recording and playback in the field. Portable recorders were connected to the camera with a multi-conductor cable terminated with multi-pin connectors on each end. The cable carried bi-directional audio, video, synchronisation, record on/off control, and power. Early studio and all portable U-Matic VCRs had a drawer-type mechanism which required the tape to be inserted, followed by manual closure of the drawer (a "top-loading" mechanism). Later studio VCRs accepted the cassette from a port opening and the cassette was pulled into and seated in the transport (a "front-loading" mechanism).

S-format tapes could be played back in older top-loading standard U-Matic decks with the aid of an adapter (the KCA-1 from Sony) which fitted around an S-sized tape; newer front-loading machines can accept S-format tapes directly, as the tapes have a slot on the underside that rides along a tab. U-Matic S tapes had a maximum recording time of 20 minutes, and large ones 1-hour, although some tape manufacturers such as 3M came out with 30-minute S-tapes and 75-minute large cassettes (and DuPont even managed 90-minute tapes)[3] by using a thinner tape. It was the U-Matic S-format decks that ushered in the beginning of ENG, or electronic news gathering.

Some U-Matic VCRs could be controlled by external video editing controllers, such as the cuts-only Sony RM-440 for linear video editing systems. Sony and other manufacturers, such as Convergence, Calaway, and CMX Systems, produced A/B roll systems, which permitted two or more VCRs to be controlled and synchronised for video dissolves and other motion effects, integration of the character generator, audio controllers and digital video effects (DVE).

In 1976, Sony introduced the semi backwards-compatible high-band Broadcast Video U-matic (BVU) format.[4] The original U-matic format became known as low-band. The BVU format had an improved colour recording system and lower noise levels. BVU gained immense popularity in ENG and location programme-making, spelling the end of 16 mm film in everyday production. By the early 1990s, Sony's 1⁄2 in (1.3 cm) Betacam SP format had all but replaced BVU outside of corporate and budget programme making. With BVU 800 series, Sony made a final improvement to BVU, by further improving the recording system and giving it the same "SP" suffix as Betacam. SP had a horizontal resolution of 330 lines. The BVU 800 series Y-FM carrier frequency was upped to 1.2 MHz giving it wider bandwidth. BVU 800 series also added Dolby audio noise reduction. Sony's BVU 900 series was the last U-matic VTR made by Sony.[5] First-generation BVU-SP and Beta-SP recordings were hard to tell apart, but despite this the writing was on the wall for the U-matic family, due to intrinsic problems with the format.

Problems

A recurring problem with the format was damage to the videotape caused by prolonged friction of the spinning video drum heads against a paused videotape. The drum would rub oxide off the tape or the tape would wrinkle; when the damaged tape was played back, a horizontal line of distorted visual image would ascend in the frame, and audio would drop out. Manufacturers attempted to minimise this issue with schemes in which the tape would loosen around the spinning head or the head would stop spinning after resting in pause mode for a pre-determined period of time.[6]

The format video image also suffered from head-switching noise, a distortion of the image in which a section of video at the bottom of the video frame would be horizontally askew from the larger portion.

The format also had difficulty reproducing the colour red, and red images would be noisier than other colours in the spectrum. For this reason, on-camera talent was discouraged from wearing red clothing that would call attention to the technical shortcoming.

Copying video from one U-matic VCR to another compromised playback reliability, and levels of head-switching noise, chroma smearing, and chroma noise compounded with every generation. These issues motivated videotape editors and engineers to use work-arounds to minimise this degradation. A time-base corrector (TBC) could be used to regenerate the sync tip portion of the video signal sent to the "recording" VCR, improving playback reliability. The "dub" cable, more formally called "demodulated" (or "demod" for short), was a multi-conductor cable that circumvented a portion of the video circuitry, minimising amplification noise.[7]

Uses

For synchronisation to broadcast or post-production editing house genlock systems, U-Matic VCRs required a time base corrector (TBC). Some TBCs had a drop-out compensation (DOC) circuit which would hold lines of video in temporary digital memory to compensate for oxide drop-out or wrinkle flaws in the videotape, however the DOC circuits required several cables and expert calibration for use.

U-matic tapes were also used for easy transport of filmed scenes for dailies in the days before VHS, DVD, and portable hard drives. Several movies have surviving copies in this form. The first rough cut of Apocalypse Now, for example (the raw version of what became Apocalypse Now Redux), survived on three U-Matic cassettes.[8]

Audio quality was compromised due the use of longitudinal audio tape heads in combination with slow tape speed. Sony eventually implemented Dolby noise reduction circuitry (using Dolby C) to improve audio fidelity.

The 2012 film No, set in 1980s Chile, used U-matic tape for filming.[9]

Digital audio

U-matic was also used for the storage of digital audio data. Most digital audio recordings from the 1980s were recorded on U-matic tape via a Sony PCM-1600, -1610, or -1630 PCM adaptor. These devices accepted stereo analogue audio, digitised it, and generated "pseudo video" from the bits, storing 48 bits—three 16-bit samples—as bright and dark regions along each scan line. (On a monitor the "video" looked like vibrating checkerboard patterns.) This could be recorded on a U-matic recorder. This was the first system used for mastering audio compact discs in the early 1980s. The famous compact disc 44.1 kHz sampling rate was based on a best-fit calculation for NTSC and PAL's video's horizontal line period and rate and U-matic's luminance bandwidth. On playback the PCM adapter converted the light and dark regions back to bits. Glass masters for audio CDs were made via laser from the PCM-1600's digital output to a photoresist- or dye-polymer-coated disc. This method was common until the mid-1990s.

Decline of use

U-matic is no longer used as a mainstream television production format, but it has found lasting appeal as a cheap, well specified, and hard-wearing format. The format permitted many broadcast and non-broadcast institutions to produce television programming on an accessible budget, spawning programming distribution, classroom playback, etc. At its peak popularity, U-matic recording and playback equipment was manufactured by Sony, Panasonic, JVC and Sharp, with many spin-off product manufacturers, such as video edit controllers, time base correctors, video production furniture, playback monitors and carts, etc.

Many television facilities the world over still have a U-matic recorder for archive playback of material recorded in the 1980s. For example, the Library of Congress facility in Culpeper, Virginia holds thousands of titles on U-matic video as a means of providing access copies and proof for copyright deposit of old television broadcasts and films.

More than four decades after it was introduced, the format is still used for the menial tasks of the industry, being more highly specialised and suited to the needs of production staff than the domestic VHS, although as time passes it has been replaced at the bottom of the tree of tape-based production formats by Betacam and Betacam SP as these in turn are replaced by Digital Betacam and HDCAM.

References

- "After exhaustive research, the development team was confident it had devised a mechanism that could be used for cassette tape VCRs, the U-loading system. The name was derived from the U-shaped figure the tape followed when seen from above." Sony History, [Sony: Freedom of Thought and Creation—the Kihara Method].

- Ascher, Steven; Pincus, Edward (4 September 2007). The Filmmaker's Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for the Digital Age. Penguin. ISBN 9781440637001 – via Google Books.

- "Billboard - July 16, 1977" (PDF). American Radio History.

- "SMPTE Journal, Volume 85, September 1976" (PDF). IEEE Xplore: 3. doi:10.5594/J07576. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "Video resolution comparison chart". Derose.net. 23 April 2003. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- Martin, Jeff (2007). "Curriculum Module 3/4" U-matic Videotape" (PDF) (pdf). New York University’s Moving Image Archiving & Preservation Program. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Samuel M. Goldwasser (7 October 2010). "Notes on the Troubleshooting and Repair of Video Cassette Recorders". repairfaq.org.

- Blake, Larry (1 August 2001). "Apocalypse Now REDUX". MixOnline. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014.

- Appelo, Tim (9 October 2012). "OCT 9 2 MOS Latin America's Frontrunner in Foreign Oscar Race is 'No,' With Gael Garcia Bernal". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

Further reading

- Fundamentals of television production, By Ralph Donald and Thomas Spann, Page 188, Ch 9.

- The History of Television, 1942 to 2000, By Albert Abramson and Christopher H. Sterling, Page 153, Ch 9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to U-Matic. |

- Sony.com Sony History

- Sony.com Sony History timeline

- Total Rewind, Umatic VCRs, Photos and comparison of various Sony U-matic decks

- Sony U.S. patent for U-matic videotape cassette, filed 1971.

- Sony U.S. patent for design of U-matic deck, filed 1971.

- Umatic Pal site Type 2 U-matic

- Umatic Pal site, History

- encyclopediapro.com U-matic page

- U-matic page in the Experimental Television Center

- R-VCR, History of Videotape U-matic page

- Rewind Museum Sony VO-1600. The worlds first VCR. 1971

- Texas Commission on the Arts, 3/4" Umatic

- U-matic PALsite information about the U-matic video format.

- Lab Guy's World Three Quarter Inch Umatic VCR's

- Trans Diffusion, Tech Mark, From Baird to MPEG, By Martin Fenton

- tvhistory.tv VCR and Home Video History