Tinirau (genus)

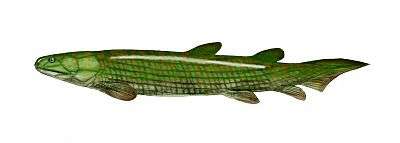

Tinirau is an extinct genus of sarcopterygian fish from the Middle Devonian of Nevada. Although it spent its entire life in the ocean, Tinirau is a stem tetrapod close to the ancestry of land-living vertebrates in the crown group Tetrapoda. Relative to more well-known stem tetrapods, Tinirau is more closely related to Tetrapoda than is Eusthenopteron, but farther from Tetrapoda than is Panderichthys. The type and only species of Tinirau is T. clackae, named in 2012.[2]

| Tinirau | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype fossil and interpretive drawing of Tinirau clackae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Eotetrapodiformes |

| Genus: | †Tinirau Swartz, 2012 |

| Type species | |

| †Tinirau clackae Swartz, 2012 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Bruehnopteron murphyi Schultze & Reed (2012)?[1] | |

Description

Tinirau was a fairly large, predatory fish about a meter long and with a deep, compact body. The head was large, with large terminal mout and numerous teeth. The tail was heterocercal, but the remaining fins with the exception of the pectoral fins was situated behind the middle of the body similar to the situation seen in pikes, giving the animal a large tail surface suitable for great bursts of speed.

It shares many advanced features with later tetrapodomorphs in the pelvic limb bones and glenoids (shoulder sockets). By the time Tinirau appeared, many stem tetrapods had already developed the three major hindlimb bones of tetrapods: the femur, tibia, and fibula. While derived stem tetrapods like Panderichthys had hindlimb configurations very similar to the first land-living tetrapods, some early forms such as Eusthenopteron possessed a prominent postaxial process of the fibula hanging over the fibulare bone below it. Tinirau is the earliest known stem tetrapod to have a significantly reduced postaxial process, and a fibula more like those of later tetrapods.[2]

Like those of the Late Devonian Panderichthys and Ichthyostega, the glenoid of Tinirau is elongated along the anteroposterior (forward-backward) axis of the body. The lengthening of the glenoid corresponds with a flattening of the proximal end of the humerus, a feature common in the forelimbs of more advanced stem tetrapods. Although the pectoral limb bones and girdle were not strong enough to support the weight of Tinirau out of water, glenoid lengthening and other changes to the proximal forelimb were among the first steps in the transformation from pectoral fin to forelimb.[2]

History

Remains of Tinirau were first discovered by paleontologist Joseph T. Gregory in 1970, who then worked for the University of California Berkeley. Gregory and his field team found these fossils near the Simpson Park Mountains in Eureka County, Nevada. They came from a deposit called the Red Hill I beds, which date to the upper Givetian stage of the Middle Devonian. The Red Hill I beds include a series of limestone and mudstone, likely deposited in an outer continental shelf marine environment. Six fossils are known, all preserving bones of the skull. Two fossils preserve postcranial bones in articulation. The holotype specimen, UCMP 118605, is a mostly complete skeleton.[2]

Tinirau clackae was named by paleontologist Brian Swartz in 2012 after Tinirau, who in Polynesian legend is the guardian of ocean life, and whose form is half human and half fish. The connection alludes to the features in Tinirau that are transitional between fish, representing life in the water, and tetrapods, representing life on land. The specific name honors Jennifer A. Clack, an English paleontologist who has made many contributions to the study of stem tetrapods.[2]

Phylogeny

In phylogenetic terms, Tinirau is positioned more crownward, or closer to Tetrapoda, than other stem tetrapods like osteolepiforms and tristichopterids. In its first description, the phylogenetic analysis of Swartz placed Tinirau as a branch directly connected to the stem of Tetrapoda. In other words, it is a close relative of the lineage leading to land vertebrates (a prehistoric taxon can rarely be identified as an ancestor of another taxon, but is instead considered a side branch in a larger lineage). Eusthenopteron, traditionally considered a direct ancestor of tetrapods, or a close relative of such an ancestor, was placed deep within the family Tristichopteridae, away from the tetrapod stem. Below is a cladogram modified from Swartz (2012) showing the placement of Tinirau:[2]

| Tetrapodomorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On the other hand, Parfitt et al. (2014) considered it more likely that Tinirau was a member of the family Tristichopteridae.[1]

References

- Matthew Parfitt; Zerina Johanson; Sam Giles; Matt Friedman (2014). "A large, anatomically primitive tristichopterid (Sarcopterygii: Tetrapodomorpha) from the Late Devonian (Frasnian) Alves Beds, Upper Old Red Sandstone, Moray, Scotland". Scottish Journal of Geology. 50 (1): 79–85. doi:10.1144/sjg2013-013.

- Swartz, B. (2012). "A marine stem-tetrapod from the Devonian of Western North America". PLoS ONE. 7 (3): e33683. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033683. PMC 3308997. PMID 22448265.