Barameda

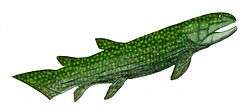

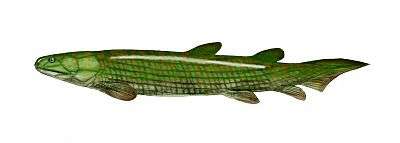

Barameda (Indigenous Australian language: "fish trap" is a genus of rhizodont lobe-finned fish which lived during the Tournaisian stage near the start of the Carboniferous period in Australia.[1] While many Paleozoic sarcopterygan fishes are identified by their fleshy lobe fins, fused skull cases and basal qualities, the primary identifier of most Barameda fossils comes from their large rooted fangs, usually 22 centimetres (8.7 in) in length, and where the order Rhizodontida and family Rhizodontidae gain their name. The largest member of this genus, Barameda decipiens, reached an estimated length of over 20 feet (6.1 m), rivaling another large rhizodont in size, Rhizodus. Species of Barameda were obligate carnivores, preying on freshwater invertebrates, early fish, and possibly early tetrapods to sustain its massive length.

| Barameda | |

|---|---|

| |

| B. decipiens | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Barameda |

| Species | |

| |

Description

The Barameda has an extremely elongated and thick body typical of Carboniferous rhizodonts, built for powerful swimming, and out-powering any prey larger than itself. It is covered with durable cosmoid scales all along its body, with thick bony plates covering its head and operculum (gill flaps), a tightly fused Skull roof, and extremely prominent, sharp fangs, devoid of serrations or cutting edges. It had an advanced lateral line system that was elaborated along its pectoral girdle, larger pectoral fins than pelvic fins, with deeply over-lapping scales along its fins, turning the pectoral fin into a large paddle. Its anal fins and secondary dorsal fins form a functional part of its tail.

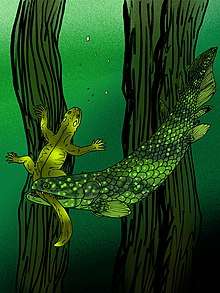

Hunting and diet

Barameda would ambush other fishes and possibly early tetrapods, although there is no evidence of these in the Mansfield deposits. It probably employed a "grab and drag" strategy using the highly pronounced fangs at their premaxillae to snag slippery prey and either thrash them at the top of the water, or drag them down and pin them under water. This hunting behavior is common amongst living members of Sarcopterygii when hunting air-breathing prey and slippery, fast moving prey. Its mandibles also rotated inwards towards each other when biting prey, securing any prey item caught from escaping. Barameda most likely used this mechanism to subdue any evasive prey that whose struggling could allow them to escape.[2]

Natural threats

Barameda was a higher trophic level predator who preyed upon a large variety of species, with no predators other than its larger relative Rhizodus. Tropical sharks during the Carboniferous were smaller than most lobefins and posed little threat to healthy adult individuals, and any large eugeneodonts such as the 21 feet (6.4 m) Parahelicoprion were restricted to open or deep-sea environments, thus isolated from larger members of Rhizodontidae.[3]

References

- Sourcebook of Biological Names and Terms, 1944, ISBN 9781258302863

- https://www.academia.edu/6746538/A_new_species_of_Barameda_Rhizodontida_and_heterochrony_in_the_rhizodontid_pectoral_fin Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 2007

- Holland, Timothy; Warren, Anne; Johanson, Zerina; Long, John; Parker, Katherine; Garvey, Jillian (1 January 2007). "A New Species of Barameda (Rhizodontida) and Heterochrony in the Rhizodontid Pectoral Fin". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (2): 295–315. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[295:ANSOBR]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 30126300.

External links

- Holland, Timothy; Warren, Anne; Johanson, Zerina; Long, John; Parker, Katherine; Garvey, Jillian (2007). "A new species of Barameda(Rhizodontida) and heterochrony in the rhizodontid pectoral fin". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (2): 295. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[295:ANSOBR]2.0.CO;2.

Long, J.A. 1989. A new rhizodontiform fish from the Early Carboniferous of Victoria, Australia, with remarks on the phylogenetic position of the group. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 9(1): 1-17. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02724634.1989.10011735