Eusthenodon

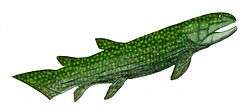

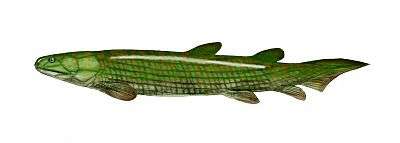

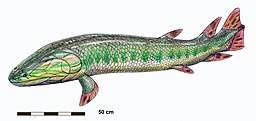

Eusthenodon (Greek for “strong-tooth” – eustheno- meaning “strength”, -odon meaning “tooth”) is an extinct genus of prehistoric tristichopterids from the Late Devonian period, ranging between 383 and 359 million years ago (Frasnian to Famennian).[1][2] They are well known for being a cosmopolitan genus with remains being recovered from East Greenland, Australia, Central Russia, South Africa, and Belgium.[3][4] Compared to the other closely related genera of the Tristichopteridae clade, Eusthenodon was one of the largest lobe-finned fishes (approximately 2.5 meters in length) and among the most derived tristichopterids alongside its close relatives Cabonnichthys and Mandageria.[5][2]

| Eusthenodon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Eotetrapodiformes |

| Family: | †Tristichopteridae |

| Genus: | †Eusthenodon Jarvik, 1952 |

| Species | |

The large size, predatory ecology, and evolutionarily derived characters possessed by Eusthenodon likely contributed to its ability to occupy and flourish in the numerous localities across the world mentioned above. Eusthenodon is attributed to being just one of many cosmopolitan genera within the "Old Red Sandstone" fish faunas of the Upper Devonian.[1][6][7] As a result, it has been hypothesized that diversification of Eusthenodon and other morphologically similar tristichopterids were not restricted by biogeographical barriers and were instead limited only by their individual ecologies and mobility.[7]

Most of the Eusthenodon remains found at these globally distributed localities consisted largely of cranial elements and largely not known from complete skeletons.[3][7][6] Consequently, the majority of available literature covering Eusthenodon primarily focus on the intricacies of the bones associated with the skull in order to investigate the genus and while others draw conclusions from the known characters of Tristichopteridae.[7] Johanson & Ahlberg (1997), in their assessment of new sarcopterygian material, present such conclusions proposing Eusthenodon likely possessed the same trifurcate or diamond-shaped caudal fin with an axial lobe turned slightly dorsally known in other tristichopterids (referred to as eusthenopterids by Johanson) along with a triangular-shaped first dorsal fin.[3]

History and discovery

In 1952, Swedish paleontologist Erik Jarvik first described the first species, Eusthenodon wangsjoi of the genus Eusthenodon.[8] The specimen was retrieved in 1936 from the richly fossiliferous sediments of the Upper Devonian sequences of East Greenland, a region that gained tremendous attraction by vertebrate paleontologists after the discovery of Ichthyostega, the earliest known tetrapod.[9] The given name of the genus, Eusthenodon, refers to the distinctly large tusks present in the upper and lower jaws.[10]

Description

Skull

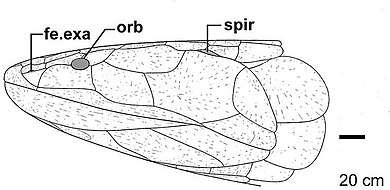

In his initial diagnosis of the first Eusthenodon remains published in 1952, Jarvik describes the features present in the remains of Eusthenodon wangsjoi including those that are significant characters of tristichopterid fishes (referred to as rhizodontids by Jarvik) as well as the traits unique to the described species and diagnostic characters of the genus.[11] The pointy head of Eusthenodon is relatively large compared to other closely related Osteolepiformes with short parietal shields that contribute towards its broad snout.[12] The frontoethmoidal shield of the cranial roof in Eusthenodon is distinctly longer than the parietal shield.[13] The ratio between the lengths of the frontoethmoidal and parietal shields has been used as a diagnostic tool by paleontologists to distinguish between taxa and in some cases, serves as the only distinctive feature separating two groups (as is seen in the separation of the clades Eusthenopteron and Tristichopterus).[6][3] Across eusthenopterids (tristichopterids), a trend exists showing increasingly higher values for this ratio in more derived genera with Eusthenodon possessing the highest value with a frontoethmoidal shield to parietal shield ratio of 2.30.[6] The further expansion of snout length in many tetrapod species may also be further evidence supporting the tendency of increasingly longer frontoethmoidal shields present in subsequent clades closely related to eusthenopterids including the late eopods.[6] The orbital fenestrae housing the small eyes of Eusthenodon were distinctly smaller in size compared to the size of the larger frontoethmoidal shield.[10][6] Residing posteriorly to the orbital fenestra, the posterior supraorbital bone extends downwards along the fenestra and comes into contact with lachrymal.[14] In contrast to other Osteolepiformes, which similarly possess a posterior supraorbital bone that extends ventrally along the orbital fenestra, the contact with the lachrymal by the posterior supraorbital bone is a diagnostic character of Eusthenodon and results in the separation of the jugal and postorbital bones from meeting the orbital fenestra.[11]

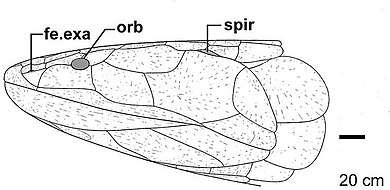

The positions and relative sizes of additional fenestra present in Eusthenodon, including the fenestra exonarina, pineal foramen, and pineal fenestra are further diagnostic characters of the genus.[10][6][2] The triangular pineal fenestra is well known in Eusthenodon for its large size and the distinctive posterior tail of the fenestra coming near or in-contact to the posterior frontal margin.[10][6] On the contrary, the pineal foramen is much smaller in size and is positioned distinctively posterior both to the center of radiation of the frontal and the postorbital bone of the frontoethmoidal shield.[10] When viewing the Eusthenodon skull in dorsal view, the fenestra exonarina can be seen positioned high and laterally in the snout.[10]

Of the three temporal bones that make up the parietal shield present in osteolepiformes (intertemporal, supratemporal, and extratemporal), the presence of the extratemporal bone in a ‘postspiracular’ position, defined as the shift of the bone from a position lateral to the supratemporal to a more posterior-lateral position, is a significant and diagnostic character of the Tristichopteridae clade.[6][14] The extratemporal bone present in Eusthenodon is notable for its complete postspiracular position resulting in no contact between the supratemporal and extratemporal bones, a condition known only to exist in Eusthenodon.[6] One theory to explain the trend observed in the posterior shift of the extratemporal bone in more derived fishes suggests that the change in head proportions contributed to a more streamlined body shape and enhanced its maneuverability and speed in its aquatic environment.[6]

The external cheek plate is well documented in Eusthenodon being 3.5 times longer than the parietal shield and 3.0 times as long as it is high.[8] The cheek plate and lower jaw in Eusthenodon are significantly longer proportionately than in any other Osteolepiformes. Eusthenodon exhibits a lower jaw that diminishes in height moving from its posterior end to anterior end and is significantly lower in height at its anterior portion. [8]

Dentition

As the name implies, Eusthenodon has large tusks that protrude from the upper and lower jaws of the skull.[14] Specifically, along the midline of the snout, two large and stout teeth emerge on the premaxilla.[3] From the incomplete material collected upon the discovery of Eusthenodon, the largest tusks are estimated to have been at least 50 millimeters in length.[8] These two teeth are anteroposteriorly flattened and have distinctive, sharp cutting edges.[6][2] In a study presented by Gael Clement in 2009, in which a newly discovered tristichopterid assemblage was described, it was found that the enlarged teeth were predominantly in line with the tooth row of the premaxilla and they did not occur in pairs.[7] Consequently, the enlarged premaxillary teeth were described as ‘pseudo fangs’ rather than the true fangs previously thought to be present in Eusthenodon.[7] A horizontal cross-sectionally analysis of the first fang reveals simple and irregularly folded orthodentine.[3] Within the pulp cavity, osteodentine is found.[6][3] The presence of the enlarged pseudo fangs on the premaxilla in Eusthenodon, supported its phylogenetic position within the Tristichopteridae clade as similar dentition patterns are found in other closely related derived tristichopterids.[7] The number of small pointed teeth along the tooth row further supports dentition trends over time as in more derived genera, a greater number of teeth are found relative to more primitive species such as Eusthenopteron.[6]

Despite possessing sets of premaxillary pseudo fangs, Eusthenodon and other large, phylogenetically derived tristichopterids exhibit elaborate anterior dentition and distinctive enlarged dentary fangs.[3][7] The faintly concave denticulated field of the parasphenoid bone is raised in primitive tristichopterids while it is notably recessed in Eusthenodon. Additionally, the presence of a distinctive blade-like vertical lamina present on the anterior coronoid exists in most other tristichopterids but is absent in derived genera such as Eusthenodon.[7] In tristichopterids, the anterior and middle coronoids carry at least a single fang pair while in Eusthenodon, the posterior coronoid possesses two fang pairs.[5][7] Furthermore, marginal coronoid teeth are known to be present in practically all other tristichopterids (except the known absence in a single genus, Cabonnicthys), yet in Eusthenodon and the closely related Mandageria, there is considerable marginal coronoid teeth missing along the anterior portion of the jaw.[6] This reduction of marginal coronoid teeth supports the phylogenetic association of Eusthenodon, Mandageria, and Cabonnichthys and serves as a derived characteristic of late tristichopterids.[6] Eusthenodon possesses a small parasymphysial plate attached to the splenial via the small attachment of the plate onto the anterior portion of the mesial lamina.[7][11] The shape and size of the parasymphysial plate exhibited in Eusthenodon is present in all tristichopterids and is a diagnostic characteristic of the family.[7][8]

Scales

In line with the features described by Berg (1955) to be the significant diagnostic characters of Tristichopteridae, Eusthenodon possesses proportionately large, distinctively round scales without cosmine that exhibit a reticular pattern of ridges with rare appearance of independent tubercles.[15][8][16] Furthermore, each of these round cosmineless scales include a proximal central attachment boss, also diagnostic of Tristichopteridae.[6][8] In contrast to most other tristichopterids, the ornamentation of Eusthenodon scales exhibit ridges forming distinct networks whereas scales from Eusthenopteron tend to have an ornamentation of considerably shorter ridges present in the incompletely fused tubercles.[8][6] The area of overlap between scales in Eusthenodon is also larger than the scales of Eusthenopteron.[8]

Classification

Eusthenodon belongs to the family Tristichopteridae, a subdivision of the order Osteolepiformes within the greater class of Sarcopterygii.[6] Sarcopterygii is the major clade that diverted from the ray-finned teleosts with the evolution of lobed-fins. The phylogeny of Tristichopteridae was described by Gael Clement, Daniel Snitting, and P.E. Ahlberg (2008) after performing a maximum parsimony analysis of the interrelationships of within the clade.[7]

| Tetrapodomorpha |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Blom, Henning; Clack, Jennifer; Ahlberg, Per. (2007). "Devonian vertebrates from East Greenland: A review of faunal composition and distribution". Geodiversitas. 29: 119–132 – via ResearchGate.

- Clement, Gael (2002). "Large Tristichopteridae (Sarcopterygii, Tetrapodomorpha) from the Late Famennian Evieux Formation of Belgium". Palaeontology. 45 (3): 577–593. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00250. ISSN 0031-0239.

- Ahlberg, Per E.; Johanson, Zerina (1997-12-15). "Second tristichopterid (Sarcopterygii, Osteolepiformes) from the Upper Devonian of Canowindra, New South Wales, Australia, and phylogeny of the Tristichopteridae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (4): 653–673. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011015. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Lebedev, O A; Zakharenko, G V; Silantiev, V V; Evdokimova, I O (2018). "New finds of fishes in the lower uppermost Famennian (Upper Devonian) of Сentral Russia and habitats of the Khovanshchinian vertebrate assemblages". Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences. 67 (1): 59. doi:10.3176/earth.2018.04. ISSN 1736-4728.

- Ahlberg, Per E.; Johanson, Zerina (1997-12-15). "Second tristichopterid (Sarcopterygii, Osteolepiformes) from the Upper Devonian of Canowindra, New South Wales, Australia, and phylogeny of the Tristichopteridae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (4): 653–673. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10011015. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Borgen, Ulf J.; Nakrem, Hans A. (2016-09-30). "Morphology, phylogeny and taxonomy of osteolepiform fish". Fossils and Strata Series. 61: 1–481. doi:10.1002/9781119286448.ch1. ISBN 9781119286431. ISSN 2637-6032.

- CLEMENT, GAËL; SNITTING, DANIEL; AHLBERG, PER ERIK (2009). "A New Tristichopterid (Sarcopterygii, Tetrapodomorpha) from the Upper Famennian Evieux Formation (Upper Devonian) of Belgium" (PDF). Palaeontology. 52 (4): 823–836. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00876.x. ISSN 0031-0239.

- Jarvik, Erik (1952). On the fish-like tail in the ichthyostegid stegocephalians : with descriptions of a new stegocephalian and new crossopterygian from the Upper Devonian of East Greenland. 114. C. A. Reitzel. pp. 54–68. OCLC 952685457.

- Jarvik, Erik (1952). On the fish-like tail in the ichthyostegid stegocephalians : with descriptions of a new stegocephalian and new crossopterygian from the Upper Devonian of East Greenland. 114. C. A. Reitzel. p. 6. OCLC 952685457.

- Jarvik, Erik (1952). On the fish-like tail in the ichthyostegid stegocephalians : with descriptions of a new stegocephalian and new crossopterygian from the Upper Devonian of East Greenland. 114. C. A. Reitzel. p. 54. OCLC 952685457.

- Jarvik, Erik (1952). On the fish-like tail in the ichthyostegid stegocephalians : with descriptions of a new stegocephalian and new crossopterygian from the Upper Devonian of East Greenland. 114. C. A. Reitzel. pp. 54–68. OCLC 952685457.

- Jarvik, Erik (1952). On the fish-like tail in the ichthyostegid stegocephalians : with descriptions of a new stegocephalian and new crossopterygian from the Upper Devonian of East Greenland. 114. C. A. Reitzel. p. 55. OCLC 952685457.

- Jarvik, Erik (1952). On the fish-like tail in the ichthyostegid stegocephalians : with descriptions of a new stegocephalian and new crossopterygian from the Upper Devonian of East Greenland. 114. C. A. Reitzel. p. 54. OCLC 952685457.

- Jarvik, Erik (1952). On the fish-like tail in the ichthyostegid stegocephalians : with descriptions of a new stegocephalian and new crossopterygian from the Upper Devonian of East Greenland. 114. C. A. Reitzel. pp. 54–68. OCLC 952685457.

- Johanson, Z.; Ritchie, A. (2000-01-01). "Rhipidistians (Sarcopterygii) from the Hunter Siltstone (Late Famennian) near Grenfell, NSW, Australia". Fossil Record. 3 (1): 111–136. doi:10.5194/fr-3-111-2000. ISSN 2193-0074.

- Berg, L. S. (1958). Translation of pp. 161-288 of System der rezenten und fossilen Fischartigen und Fische by Berg 1955. OCLC 1081960984.