Ten Years' War

The Ten Years' War (Spanish: Guerra de los Diez Años) (1868–1878), also known as the Great War (Guerra Grande) and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. The uprising was led by Cuban-born planters and other wealthy natives. On October 10, 1868 sugar mill owner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and his followers proclaimed independence, beginning the conflict. This was the first of three liberation wars that Cuba fought against Spain, the other two being the Little War (1879–1880) and the Cuban War of Independence (1895–1898). The final three months of the last conflict escalated with United States involvement, leading to the Spanish–American War.[10][11]

| Ten Years' War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

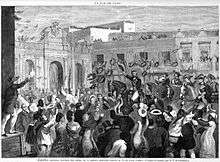

Painting: Embarkation of the Catalan Volunteers from the Port of Barcelona | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: Puerto Rican, Dominican and Mexican volunteers[1] |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

10,000-20,000 in 1869[2] 10,000-12,000 in 1873[3] +8,000 in 1878 |

181,000 (mobilized throughout the war) [4] 30,000 (1868)[5] 40,000 (late 1869)[2] 55,000 (1870)[6] 30,000 (1875)[7] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

~50,000[8] -100,000[9] dead 40,000 guerrillas killed (25,000 due to illness and repression)[9] 60,000 civilians killed[9] |

81,248[4]-90,000[9] dead 81,000 soldiers killed (54,000 due to illness)[9] 3,200 dead marines[9] 1,700 dead sailors[9] 5,000 dead Cubans[9] | ||||||

Background

Slavery

Cuban business owners demanded fundamental social and economic reforms from Spain, which ruled the colony. Lax enforcement of the slave trade ban had resulted in a dramatic increase in imports of Africans, estimated at 90,000 slaves from 1856 to 1860. This occurred despite a strong abolitionist movement on the island, and rising costs among the slave-holding planters in the east. New technologies and farming techniques made large numbers of slaves unnecessary and prohibitively expensive. In the economic crisis of 1857 many businesses failed, including many sugar plantations and sugar refineries. The abolitionist cause gained strength, favoring a gradual emancipation of slaves with financial compensation from Spain for slaveholders. Additionally, some planters preferred hiring Chinese immigrants as indentured workers and in anticipation of ending slavery. Before the 1870s, more than 125,000 were recruited to Cuba. In May 1865, Cuban creole elites placed four demands upon the Spanish Parliament: tariff reform, Cuban representation in Parliament, judicial equality with Spaniards, and full enforcement of the slave trade ban.[12]

Colonial policies

The Spanish Parliament at the time was changing; gaining much influence were reactionary, traditionalist politicians who intended to eliminate all liberal reforms. The power of military tribunals was increased; the colonial government imposed a six percent tax increase on the Cuban planters and businesses. Additionally, all political opposition and the press were silenced. Dissatisfaction in Cuba spread on a massive scale as the mechanisms to express it were restricted. This discontent was particularly felt by the powerful planters and hacienda owners in Eastern Cuba.[13]

The failure of the latest efforts by the reformist movements, the demise of the "Information Board," and another economic crisis in 1866/67 heightened social tensions on the island. The colonial administration continued to make huge profits which were not re-invested in the island for the benefit of its residents. It funded military expenditures (44% of the revenue), colonial government's expenses (41%), and sent some money to the Spanish colony of Fernando Po (12%). The Spaniards, representing 8% of the island's population, were appropriating over 90% of the island’s wealth. In addition, the Cuban-born population still had no political rights and no representation in Parliament. Objections to these conditions sparked the first serious independence movement, especially in the eastern part of the island.

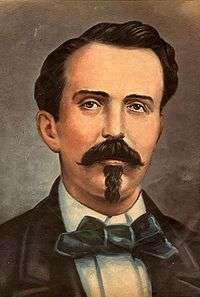

Revolutionary conspiracy

In July 1867, the "Revolutionary Committee of Bayamo" was founded under the leadership of Cuba’s wealthiest plantation owner, Francisco Vicente Aguilera. The conspiracy rapidly spread to Oriente’s larger towns, most of all Manzanillo, where Carlos Manuel de Céspedes became the main protagonist of the uprising in 1868. Originally from Bayamo, Céspedes owned an estate and sugar mill known as La Demajagua. The Spanish, aware of Céspedes’ anti-colonial intransigence, tried to force him into submission by imprisoning his son Oscar. Céspedes refused to negotiate and Oscar was executed.

Tensions in the United States

For the United States, the war carried an anti-Catholic dimension as part of the tense relations between American Catholics and Protestants. From the viewpoint of the United States, Spanish colonial power was an obstacle to American expansion and dominance. The American Protective Association, a 19th century anti-Catholic organization, passed resolutions condemning the "ecclesiastical dominion and inquisitorial persecution" of Cubans. While not opposing American interests in the conflict, American Catholics were joined by some Protestant clergy in their objections to the denigration of the church, and William Croswell Doane criticized a resolution adopted by the New York Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church being based on "their hatred of the Roman Catholic faith."[16]

History

Uprising

Cespedes and his followers had planned the uprising to begin October 14, but it had to be moved up four days earlier, because the Spaniards had discovered their plan of revolt. In the early morning of October 10, Céspedes issued the cry of independence, the "10th of October Manifesto" at La Demajagua, which signaled the start of an all-out military uprising against Spanish rule in Cuba. Cespedes freed his slaves and asked them to join the struggle. October 10 is now commemorated in Cuba as a national holiday under the name Grito de Yara ("Cry of Yara").[17]

During the first few days, the uprising almost failed: Céspedes intended to occupy the nearby town of Yara on October 11. In spite of this initial setback, the uprising of Yara was supported in various regions of the Oriente province, and the independence movement continued to spread throughout the eastern region of Cuba. On October 13, the rebels took eight towns in the province that favored the insurgency and acquisition of arms. By October's end, the insurrection had enlisted some 12,000 volunteers.

Military responses

That same month, Máximo Gómez taught the Cuban forces what would be their most lethal tactic: the machete charge. He was a former cavalry officer for the Spanish Army in the Dominican Republic.[18] Forces were taught to combine use of firearms with machetes, for a double attack against the Spanish. When the Spaniards (following then-standard tactics) formed a square, they were vulnerable to rifle fire from infantry under cover, and pistol and carbine fire from charging cavalry. In the event, as with the Haitian Revolution, the European forces suffered the most fatalities due to yellow fever because the Spanish-born troops had no acquired immunity to this endemic tropical disease of the island.

10th of October Manifesto

Carlos Manuel de Céspedes called on men of all races to join the fight for freedom. He raised the new flag of an independent Cuba,[19] and rang the bell of the mill to celebrate his proclamation from the steps of the sugar mill of the manifesto signed by him and 15 others. It cataloged Spain's mistreatment of Cuba and then expressed the movement's aims:[20]

Our aim is to enjoy the benefits of freedom, for whose use, God created man. We sincerely profess a policy of brotherhood, tolerance, and justice, and to consider all men equal, and to not exclude anyone from these benefits, not even Spaniards, if they choose to remain and live peacefully among us.

Our aim is that the people participate in the creation of laws, and in the distribution and investment of the contributions.

Our aim is to abolish slavery and to compensate those deserving compensation. We seek freedom of assembly, freedom of the press and the freedom to bring back honest governance; and to honor and practice the inalienable rights of men, which is the foundations of the independence and the greatness of a people.

Our aim is to throw off the Spanish yoke, and to establish a free and independent nation….

When Cuba is free, it will have a constitutional government created in an enlightened manner.

Escalation

After three days of combat, the rebels seized the important city of Bayamo. In the enthusiasm of this victory, poet and musician Perucho Figueredo composed Cuba’s national anthem, "La Bayamesa”. The first government of the Republic in Arms, headed by Céspedes, was established in Bayamo. The city was retaken by the Spanish after 3 months on January 12, but the fighting had burned it to the ground.

The war spread in Oriente: on November 4, 1868, Camagüey rose up in arms and, in early February 1869, Las Villas followed. The uprising was not supported in the westernmost provinces of Pinar del Río, Havana and Matanzas. With few exceptions (Vuelta Abajo), resistance was clandestine. A staunch supporter of the rebellion was José Martí who, at the age of 16, was detained and condemned to 16 years of hard labour. He was later deported to Spain. Eventually he developed as a leading Latin American intellectual and Cuba’s foremost national hero, its primary architect of the 1895–98 Cuban War of Independence.

After some initial victories and defeats, in 1868 Céspedes replaced Gomez as head of the Cuban Army with United States General Thomas Jordan, a veteran of Confederate States Army in the American Civil War. He brought a well-equipped force, but General Jordan's reliance on regular tactics, although initially effective, left the families of Cuban rebels far too vulnerable to the "ethnic cleansing" tactics of the ruthless Blas Villate, Count of Valmaceda (also spelled Balmaceda). Valeriano Weyler, known as the "Butcher Weyler" in the 1895–1898 War, fought along the Count of Balmaceda.

After General Jordan resigned and returned to the US, Cespedes returned Máximo Gómez to his command. Gradually a new generation of skilled battle-tested Cuban commanders rose from the ranks, including Antonio Maceo Grajales, José Maceo, Calixto García, Vicente Garcia González[22] and Federico Fernández Cavada. Raised in the United States and with an American mother, Fernández Cavada had served as a Colonel in the Union Army during the American Civil War. His brother Adolfo Fernández Cavada also joined the Cuban fighting for independence. On April 4, 1870, the senior Federico Fernández Cavada was named Commander-in-Chief of all the Cuban forces.[23] Other war leaders of note fighting on the Cuban Mambí side included Donato Mármol, Luis Marcano-Alvarez, Carlos Roloff, Enrique Loret de Mola, Julio Sanguily, Domingo Goicuría, Guillermo Moncada, Quentin Bandera, Benjamín Ramirez, and Julio Grave de Peralta.

Constitutional assembly

On April 10, 1869, a constitutional assembly took place in the town of Guáimaro (Camagüey). It was intended to provide the revolution with greater organizational and juridical unity, with representatives from the areas that had joined the uprising. The assembly discussed whether a centralized leadership should be in charge of both military and civilian affairs, or if there should be a separation between civilian government and military leadership, the latter being subordinate to the first. The overwhelming majority voted for the separation option. Céspedes was elected president of this assembly; and General Ignacio Agramonte y Loynáz and Antonio Zambrana, principal authors of the proposed Constitution, were elected secretaries. After completing its work, the Assembly reconstituted itself as the House of Representatives and the state’s supreme power. They elected Salvador Cisneros Betancourt as president, Miguel Gerónimo Gutiérrez as vice-president, and Agramonte and Zambrana as secretaries. Céspedes was elected on April 12, 1869, as the first president of the Republic in Arms and General Manuel de Quesada (who had fought in Mexico under Benito Juárez during the French invasion of that country), as Chief of the Armed Forces.

Spanish repressions

By early 1869, the Spanish colonial government had failed to reach an agreement with the insurrection forces; they opened a war of extermination. The colonial government passed several laws: arrested leaders and collaborators of the insurgency were to be executed on the spot, ships carrying weapons would be seized and all persons on board immediately executed, males 15 and older caught outside of their plantations or places of residence without justification would be summarily executed, all towns were ordered to raise the white flag or otherwise be burnt to the ground, and any woman caught away from her farm or place of residence would be taken to camps in cities.

Apart from its own army, the government relied on the Voluntary Corps, a militia recruited a few years earlier to face the announced invasion by Narcisco López. The Corps became notorious for its harsh and bloody acts. Its forces executed eight students from the University of Havana on November 27, 1871. The Corps seized the steamship Virginius in international waters on October 31, 1873. Starting on November 4, its forces executed 53 persons, including the captain, most of the crew, and a number of Cuban insurgents on board. The serial executions were stopped only by the intervention of a British man-of-war under the command of Sir Lambton Lorraine.

In the so-called "Creciente de Valmaseda" incident, the Corps captured farmers (Guajiros) and the families of Mambises, killing them immediately or sending them en masse to concentration camps on the island. The Mambises fought using guerrilla tactics and were more effective on the eastern side of the island than in the west, where they lacked supplies.

Another Voluntary Corps was formed by Germans, the so-called "Club des Alemanes". Presided by Fernando Heydrich, a committee of German merchants and landowners created a troop to defend their possessions in 1870. A neutral force initially, as ordered by Otto von Bismarck in a telegram to consul Luis Will, they were considered to favor the government.[26]

Rebel political strife

Ignacio Agramonte was killed by a stray bullet on May 11, 1873 and was replaced in the command of the central troops by Máximo Gómez. Because of political and personal disagreements and Agramonte's death, the Assembly deposed Céspedes as president, replacing him with Cisneros. Agramonte had realized that his dream Constitution and government were ill-suited to the Cuban Republic in Arms, which was the reason he quit as Secretary and assumed command of the Camaguey region. He became a supporter of Cespedes. Céspedes was later surprised and killed on February 27, 1874 by a swift-moving patrol of Spanish troops. The new Cuban government had left him with only one escort and denied permission to leave Cuba for the US, from where he intended to help prepare and send armed expeditions.

Continued warfare

Activities in the Ten Years' War peaked in the years 1872 and 1873, but after the deaths of Agramonte and Céspedes, Cuban operations were limited to the regions of Camagüey and Oriente. Gómez began an invasion of Western Cuba in 1875, but the vast majority of slaves and wealthy sugar producers in the region did not join the revolt. After his most trusted general, the American Henry Reeve, was killed in 1876, Gómez ended his campaign.

Spain's efforts to fight were hindered by the civil war (Third Carlist War) that broke out in Spain in 1872. When the civil war ended in 1876, the government sent more Spanish troops to Cuba, until they numbered more than 250,000. The severe Spanish measures weakened the liberation forces ruled by Cisneros. Neither side in the war was able to win a single concrete victory, let alone crush the opposing side to win the war, but in the long run Spain gained the upper hand.

Failing insurgency

The deep divisions among insurgents regarding their organisation of government and the military became more pronounced after the Assembly of Guáimaro, as resulting in the dismissal of Céspedes and Quesada in 1873. The Spanish exploited regional divisions, as well as fears that the slaves of Matanzas would break the weak existing balance between whites and blacks. The Spanish changed their policy towards the Mambises, offering amnesties and reforms.

The Mambises did not prevail for a variety of reasons: lack of organization and resources; lower participation by whites; internal racist sabotage (against Maceo and the goals of the Liberating Army); the inability to bring the war to the western provinces (Havana in particular); and opposition by the US government to Cuban independence. The US sold the latest weapons to Spain, but not to the Cuban rebels.[28]

Peace negotiations and hold-outs

Tomás Estrada Palma succeeded Juan Bautista Spotorno as president of the Republic in Arms. Estrada Palma was captured by Spanish troops on October 19, 1877. As a result of successive misfortunes, on February 8, 1878, the constitutional organs of the Cuban government were dissolved; the remaining leaders among the insurgents started negotiating for peace in Zanjón, Puerto Príncipe.

General Arsenio Martínez Campos, in charge of applying the new policy, arrived in Cuba. It took him nearly two years to convince most of the rebels to accept the Pact of Zanjón; it was signed on February 10, 1878, by a negotiating committee. The document contained most of the promises made by Spain. The Ten Years' War came to an end, except for the resistance of a small group in Oriente led by General Garcia and Antonio Maceo Grajales, who protested in Los Mangos de Baraguá on March 15.

Aftermath

Pact of Zanjón

Under the terms of the pact, a constitution and a provisional government was set up, but the revolutionary élan was gone. The provisional government convinced Maceo to give up, and with his surrender, the war ended on May 28, 1878. Many of the graduates of the Ten Years' War became central players in Cuba's War of Independence that started in 1895. These include the Maceo brothers, Maximo Gómez, Calixto Garcia and others.[28]

The Pact of Zanjón promised various reforms to improve the financial situation for residents of Cuba. The most significant reform was the manumission of all slaves who had fought for Spain. Abolition of slavery had been proposed by the rebels, and many persons loyal to Spain also wanted to abolish it. Finally in 1880, the Spanish legislature abolished slavery in Cuba and other colonies in a form of gradual abolition. The law required slaves to continue to work for their masters for a number of years, in a kind of indentured servitude, but masters had to pay the slaves for their work. The wages were so low, however, that the freedmen could barely support themselves.

Remaining tensions

After the war ended, tensions between Cuban residents and the Spanish government continued for 17 years. This period, called "The Rewarding Truce", included the outbreak of the Little War (La Guerra Chiquita) between 1879 and 1880. Separatists in that conflict became supporters of José Martí, the most passionate of the rebels who chose exile over Spanish rule. Overall, about 200,000 people lost their lives in the conflict. Together with a severe economic depression throughout the island, the war devastated the coffee industry, and American tariffs badly damaged Cuban exports.

See also

- Ana Betancourt – a female "Mambisa" who used the war to campaign for women's equality

- Cuban War of Independence

- Francisco Gonzalo Marín

- History of Cuba

- José Semidei Rodríguez

- Juan Bautista Spotorno

- Juan Ríus Rivera

- Little War (Cuba)

- Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant#Cuban insurrection

Notes

- Clodfelter 2017, p. 306.

- Thomas, Hugh Swynnerton (1973). From Spanish domination to American domination, 1762-1909. Volume I of `` Cuba: the struggle for freedom, 1762-1970 . Barcelona; Mexico: Grijalbo, pp. 337. Edition of Neri Daurella. ISBN 9788425302916.

- Thomas, 1973: 345. 1,500 to 2,000 rebels fled to Jamaica.

- Ramiro Guerra Sánchez (1972). War of the 10 i.e. Ten years. Volume II Havana: Editorial De Ciencias Sociales, pp. 377

- Florencio León Gutiérrez (1895). "Conference on the Cuban insurrection." Havana: Artillery Corps Printing, pp. 25

- José Andrés-Gallego (1981). General History of Spain and America: Revolution and Restoration: (1868-1931) . Madrid: Rialp Editions, pp. 271. ISBN 978-8-43212-114-2. 20,000 Spaniards and 35,000 Cubans.

- Nicolás María Serrano & Melchor Pardo (1875). Annals of the civil war: Spain from 1868 to 1876 . Volume I. Madrid: Astort Brothers, pp. 1263

- as estimated by José Martí in his work "The Revolution of 1868" cited by Samuel Silva Gotay in "Catholicism and politics in Puerto Rico: under Spain and the United States" p. 39

- "Military Historical Victimary".

- Charles Campbell, The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant (2017) pp 179-98.

- Hugh Thomas, Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom (1971) pp 244-263.

- Arthur F. Corwin, Spain and the Abolition of Slavery in Cuba, 1817-1886 (1967)

- Pérez, Louis A., Jr. (2006). Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 80–89. ISBN 978-0-19-517911-8.

- Reuter, F. T. (2014). Catholic Influence on American Colonial Policies, 1898-1904. (n.p.): University of Texas Press.

- Hughes, Susan; Fast, April (2004). Cuba: The Culture. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 6. ISBN 9780778793267. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2005-12-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- es:Grito de Yara

- http://www.autentico.org/oa09138.php

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2005-03-19. Retrieved 2005-12-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Latino Experience in U.S. History"; publisher: Globe Pearson; pp. 155–57; ISBN 0-8359-0641-8

- Gutiérrez, Luis Alvarez (1988). La diplomacia bismarckiana ante la cuestión cubana, 1868–1874 (in Spanish). Editorial CSIC – CSIC Press. ISBN 9788400068936.

- "The Ten Year War", History of Cuba website

References

- Perez Jr., Louis A (1988). Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Navarro, José Cantón (1998). History of Cuba: The Challenge of the Yoke and the Star. Havana, Cuba: Editorial SI-MAR S. A. ISBN 959-7054-19-1.

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015 (4th ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-7470-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Portions of this article were extracted from CubaGenWeb.

- Benjamin, Jules R. The United States and the Origins of the Cuban Revolution: An Empire of Liberty in an Age of National Liberation (1990) pp 13-19.

- Campbell, Charles. The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant (2017) pp 179-98.

- Campbell, Charles. The Transformation of American Foreign Relations (1976) pp 53-59.

- Chapin, James. "Hamilton Fish and the Lessons of the Ten Years' War," in Jules Davids, ed., Perspectives in American Diplomacy (1976) pp 131-163, 33p.

- Corwin, Arthur F. Spain and the Abolition of Slavery in Cuba, 1817-1886 (1967)

- Ferrer, Ada. Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868-1898 (1999)

- Gott, Richard. Cuba: A New History (2004) pp 71-83,

- Hernandez, Jose M. Cuba and the United States: Intervention and Militarism, 1868-1933 (1993) pp p6-15.

- Langley, Lester D. The Cuban Policy of the United States: A Brief History (1968) pp 53-81.

- Nevins, Allan. Hamilton Fish: The Inner History of the Grant Administration (1936) 1:176-200, 2:667-694..

- Padilla, Andrés Sánchez. Enemigos íntimos: España y los Estados Unidos antes de la Guerra de Cuba (1865-1898) (Universitat de València, 2016).

- Pérez, Louis A., Jr. Cuba and the United States: Ties of Singular Intimacy (1990) pp 50-54.

- Priest, Andrew. "Thinking about Empire: The administration of Ulysses S. Grant, Spanish colonialism and the ten years' war in Cuba." Journal of American Studies 48.2 (2014): 541-558. online

- Sexton, Jay. "The United States, the Cuban rebellion, and the multilateral initiative of 1875." Diplomatic History 30.3 (2006): 335-365.

- Thomas, Hugh. Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom (1971) pp 244-263.

- Pirala, Antonio. Anales de la Guerra en Cuba, (1895, 1896 and some from 1874) Felipe González Rojas (Editor), Madrid. This may still be the most detailed source for information on the Ten Years' War.

- Ziegler, Vanessa Michelle. "The revolt of "the Ever-faithful Isle": the Ten Years' War in Cuba, 1868–1878". PhD dissertation. [Santa Barbara, Calif.]: University of California, Santa Barbara, 2007. Electronic Dissertations D16.5.C2 S25 ZIEV 2007 [Online]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ten Years' War. |