Lotosaurus

Lotosaurus is an extinct genus of sail-backed poposauroid known from Hunan Province of central China.[1]

| Lotosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| A mounted skeleton of Lotosaurus at the Beijing Museum of Natural History. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Paracrocodylomorpha |

| Branch: | †Poposauroidea |

| Family: | †Lotosauridae Zhang, 1975 |

| Genus: | †Lotosaurus Zhang, 1975 |

| Type species | |

| †Lotosaurus adentus Zhang, 1975 | |

Discovery

Lotosaurus is known from the holotype IVPP V 4881 (or possibly V 4880), an articulated and well-preserved skeleton. Other referred specimens include IVPP V 48013 (a skull) as well as many articulated and disarticulated skeletal remains concentrated in a bonebed which is almost completely composed of Lotosaurus bones. All known specimens of this genus were collected from this bonebed, known as the Lotosaurus site, which belongs to the Batung Formation (or alternatively Xinlingzhen Formation of the Badong Group[2]).

Further excavations in 2018 revealed many more specimens, as well as geological and environmental details of the Lotosaurus site. At least 38 individuals of various ages died within this one location.[3]

Lotosaurus was first named by Fa-kui Zhang in 1975 and the type species is Lotosaurus adentus. Lotosaurus was originally placed in its own family, Lotosauridae, which named by Zhang in 1975. The specific name is derived from the Greek a and denta, meaning "toothless", in reference to its toothless beak.[4]

Description

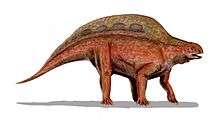

Lotosaurus was 1.5 to 2.5 m (4.9 to 8.2 ft) long and a heavily built quadruped. It was a herbivore, shearing off leaves with its toothless, beaked jaws. Lotosaurus, like some other members of the Poposauroidea, had a sail on its back, granting it an appearance superficially similar to that of Permian pelycosaurs like Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus, although not as high.[5]

Classification

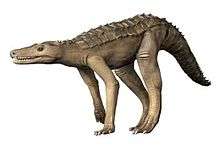

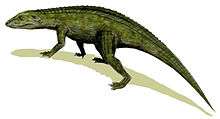

Lotosaurus was originally thought to be a thecodont, probably related to Ctenosauriscus and other archosaur taxa with elongated neural spines (=Ctenosauriscidae).[4] Although modern cladistic analyses have abandoned the order Thecodontia, they have also supported the theory that Lotosaurus was a distant relative of ctenosauriscids. Nesbitt (2007) was the first to suggest that Lotosaurus is more closely related to Shuvosaurus (a shuvosaurid) than to Arizonasaurus (a ctenosauriscid).[6] In his massive revision of archosaurs which included a large cladistic analysis, Sterling J. Nesbitt (2011) found Lotosaurus to be a member of the group Poposauroidea. Poposauroids were part of Pseudosuchia, the lineage of reptiles which also includes aetosaurs, raisuchids, and modern crocodilians.

Within Poposauroidea, Lotosaurus was placed as a relative of the Shuvosauridae, and therefore it is not included in the Ctenosauriscidae. Although shuvosaurids walked on two legs and lacked sails, their toothless beaks and presumed herbivorous habits resembled those of Lotosaurus. Ctenosauriscids were carnivores with many sharp teeth and high, theropod-like skulls, in contrast to Lotosaurus and shuvosaurids. Nevertheless, Lotosaurus is still considered a distant relative of ctenosauriscids, as that family is also placed within Poposauroidea.[1] Further studies confirmed these results.[2]

Paleoecology and taphonomy

The Lotosaurus site was once believed to have been as old as the Anisian stage of the early Middle Triassic, about 245-237 million years ago.[1] However, a 2018 analysis suggested a younger date based on Uranium-Lead dating from 189 sampled Zircon grains. The youngest grain sampled gave a date of 225.6 mya, In the early Norian stage of the Late Triassic. However, this grain is an lone outlier in the sample, indicating that it may have leaked lead. Using the next youngest grains, which were clustered in a set and probably more reliable, the weighted mean age of the bonebed was found to be either 238.9 to 229.3 mya (considering the lower intercept of the U-Pb graph), or 244.3 to 228.3 mya (considering the mean age of the youngest cluster of grains). Of these two options, the former has less deviation between ages and may be more accurate. Regardless, the age of the bonebed has only a small chance of belonging to the Anisian stage, and the Lotosaurus specimens which died within the bonebed were more likely to have been alive during the Ladinian or Carnian stages of the Late Middle Triassic or early Late Triassic.[3] A subsequent 2019 study weighted mean age of 238.0 ± 1.4 Ma (Ladinian) as the maximum depositional age for the sandstones preserving fossils of Lotosaurus.[7]

The Lotosaurus site was once near the northern shore of the South China Craton, a subcontinent which drifted through Tethys ocean during the Middle Triassic. The South China Craton collided with the North China Craton and the rest of Laurasia at approximately the same time as some of the estimated ages of the site. As a result, it cannot be determined if Lotosaurus was endemic to the SCC while the subcontinent remained an island, or immigrated to the SCC from the NCC after the two merged. Considering that close relatives of Lotosaurus (the shuvosaurids) lived in other regions of Pangaea around that time, the latter hypothesis is currently believed to be more likely. The mineral and microfossil composition of the site suggests that it was a subtropical environment, with pronounced wet and dry seasons. The bonebed in particular would have been part of a floodplain or stream according to ripple marks within the rocks.

The large number of individuals within a small area indicate that all of the animals died at around the same time. However, their bones are well preserved and minimally scattered, indicating that the cause of death was not a catastrophic event such as a flood or mudslide. It has been suggested that the group perished due to thirst or sickness during the dry season, perhaps while gathered around an evaporating or contaminated watering hole. Their rotting carcasses would have soon afterwards been covered in water and sediment upon the arrival of the wet season, which would explain the apparent but slight scattering of bones.[3]

References

- Sterling J. Nesbitt (2011). "The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origin of Major Clades" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292. doi:10.1206/352.1.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Richard J. Butler; Stephen L. Brusatte; Mike Reich; Sterling J. Nesbitt; Rainer R. Schoch; Jahn J. Hornung (2011). "The sail-backed reptile Ctenosauriscus from the latest Early Triassic of Germany and the timing and biogeography of the early archosaur radiation". PLoS ONE. 6 (10): e25693. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025693. PMC 3194824. PMID 22022431.

- Hagen, Cedric J.; Roberts, Eric M.; Sullivan, Corwin; Liu, Jun; Wang, Yanyin; Agyemang, Prince C. Owusu; Xu, Xing (2018-03-01). "Taphonomy, geological age, and paleobiogeography of lotosaurus adentus (archosauria: poposauroidea) from the middle-upper triassic badong formation, hunan, china". Palaios. 33 (3): 106–124. doi:10.2110/palo.2017.084. ISSN 0883-1351.

- Fa-kui Zhang (1975). "A new thecodont Lotosaurus, from Middle Triassic of Hunan". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 13 (3): 144–147.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Benson, R.B.J. & Brussatte, S. (2012). Prehistoric Life. Dorling Kindersley. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-7566-9910-9.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Sterling J. Nesbitt (2007). "The anatomy of Effigia okeeffeae (Archosauria, Suchia), theropod-like convergence, and the distribution of related taxa" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 302: 84 pp. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2007)302[1:TAOEOA]2.0.CO;2.

- Jun Wang; Rui Pei; Jianye Chen; Zhenzhu Zhou; Chongqin Feng; Su-Chin Chang (2019). "New age constraints for the Middle Triassic archosaur Lotosaurus: Implications for basal archosaurian appearance and radiation in South China". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 521: 30–41. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2019.02.008.