Pachycephalosaurus

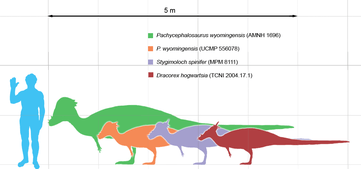

Pachycephalosaurus (/ˌpækɪˌsɛfələˈsɔːrəs/[1]; meaning "thick-headed lizard," from Greek pachys-/παχύς- "thick", kephale/κεφαλή "head" and sauros/σαῦρος "lizard") is a genus of pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs. The type species, P. wyomingensis, is the only known species. It lived during the Late Cretaceous Period (Maastrichtian stage) of what is now North America. Remains have been excavated in Montana, South Dakota, Wyoming and Alberta. It was a herbivorous creature which is primarily known from a single skull and a few extremely thick skull roofs, though more complete fossils have been found in recent years. Pachycephalosaurus was one of the last non-avian dinosaurs before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. Another dinosaur, Tylosteus of western North America, has been synonymized with Pachycephalosaurus, as have the genera Stygimoloch and Dracorex in recent studies.[2][3]

| Pachycephalosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of the "Sandy" specimen, Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Family: | †Pachycephalosauridae |

| Tribe: | †Pachycephalosaurini |

| Genus: | †Pachycephalosaurus Brown & Schlaikjer, 1943 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

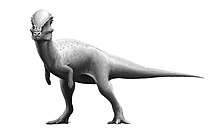

Like other pachycephalosaurids, Pachycephalosaurus was a bipedal herbivore with an extremely thick skull roof. It possessed long hindlimbs and small forelimbs. Pachycephalosaurus is the largest-known pachycephalosaur. The thick skull domes of Pachycephalosaurus and related genera gave rise to the hypothesis that pachycephalosaurs used their skulls in intra-species combat. This hypothesis has been disputed in recent years.

History of discovery

.jpg)

Remains attributable to Pachycephalosaurus may have been found as early as the 1850s. As determined by Donald Baird, in 1859 or 1860 Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, an early fossil collector in the North American West, collected a bone fragment in the vicinity of the head of the Missouri River, from what is now known to be the Lance Formation in southeastern Montana.[4] This specimen, now ANSP 8568, was described by Joseph Leidy in 1872 as belonging to the dermal armor of a reptile or an armadillo-like animal.[5] It became known as Tylosteus. Its actual nature was not found until Baird restudied it over a century later and identified it as a squamosal (bone from the back of the skull) of Pachycephalosaurus, including a set of bony knobs corresponding to those found on other specimens of Pachycephalosaurus.[4] Because the name Tylosteus predates Pachycephalosaurus, according to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature Tylosteus would normally be preferred. In 1985, Baird successfully petitioned to have Pachycephalosaurus used instead of Tylosteus because the latter name had not been used for over fifty years, was based on undiagnostic materials, and had poor geographic and stratigraphic information.[6][7] This may not be the end of the story; Robert Sullivan suggested in 2006 that ANSP 8568 is more like the corresponding bone of Dracorex than that of Pachycephalosaurus.[8] The issue is of uncertain importance, though, if Dracorex actually represents a juvenile Pachycephalosaurus, as has been recently proposed.[9]

P. wyomingensis, the type and currently only valid species of Pachycephalosaurus, was named by Charles W. Gilmore in 1931. He coined it for the partial skull USNM 12031, from the Lance Formation of Niobrara County, Wyoming. Gilmore assigned his new species to Troodon as T. wyomingensis.[10] At the time, paleontologists thought that Troodon, then known only from teeth, was the same as Stegoceras, which had similar teeth. Accordingly, what are now known as pachycephalosaurids were assigned to the family Troodontidae, a misconception not corrected until 1945, by Charles M. Sternberg.[11]

In 1943, Barnum Brown and Erich Maren Schlaikjer, with newer, more complete material, established the genus Pachycephalosaurus. They named two species: Pachycephalosaurus grangeri, the type species of the genus Pachycephalosaurus, and Pachycephalosaurus reinheimeri. P. grangeri was based on AMNH 1696, a nearly complete skull from the Hell Creek Formation of Ekalaka, Carter County, Montana. P. reinheimeri was based on what is now DMNS 469, a dome and a few associated elements from the Lance Formation of Corson County, South Dakota.[12] They also referred the older species "Troodon" wyomingensis to their new genus. Their two newer species have been considered synonymous with P. wyomingensis since 1983.[13]

In 2015, some pachycephalosaurid material and a domed parietal attributable to Pachycephalosaurus were discovered in Scollard Formation, Alberta, Canada, implying dinosaurs of this era were cosmopolitan and didn't have discrete faunal provinces. [14]

Description

The anatomy of Pachycephalosaurus is poorly known, as only skull remains have been described.[8] Pachycephalosaurus is famous for having a large, bony dome atop its skull, up to 25 cm (10 in) thick, which safely cushioned its tiny brain. The dome's rear aspect was edged with bony knobs and short bony spikes projected upwards from the snout. The spikes were probably blunt, not sharp.[15]

The skull was short, and possessed large, rounded eye sockets that faced forward, suggesting that the animal had good eyesight and was capable of binocular vision. Pachycephalosaurus had a small muzzle which ended in a pointed beak. The teeth were tiny, with leaf-shaped crowns. The head was supported by an "S"- or "U"-shaped neck.[15] Younger individuals of Pachycephalosaurus maybe have had flatter skulls, with larger horns projecting from the back of the skull. As the animal grew, the horns shrunk and rounded out, as the dome grew.[2][3]

Pachycephalosaurus was probably bipedal and was the largest of the pachycephalosaurid (bone-headed) dinosaurs. It has been estimated that Pachycephalosaurus was about 4.5 metres (14.8 ft) long and weighed about 450 kilograms (990 lb).[16] Based on other pachycephalosaurids, it probably had a fairly short, thick neck, short fore limbs, a bulky body, long hind legs and a heavy tail, which was likely held rigid by ossified tendons.[17]

Classification

Pachycephalosaurus gives its name to the Pachycephalosauria, a clade of herbivorous ornithischian ("bird hipped") dinosaurs which lived during the Late Cretaceous Period in North America and Asia. Despite their bipedal stance, they were likely more closely related to the ceratopsians than the ornithopods.[18]

Pachycephalosaurus is the most famous member of the Pachycephalosauria (though not the best-preserved member). The clade also includes Stenopelix, Wannanosaurus, Goyocephale, Stegoceras, Homalocephale, Tylocephale, Sphaerotholus and Prenocephale. Within the tribe Pachycephalosaurini, Pachycephalosaurus is most closely related to Alaskacephale. Dracorex and Stygimoloch have been synonymized with Pachycephalosaurus.[9][2]

Below is a cladogram modified from Evans et al., 2013.[19]

| Pachycephalosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Growth

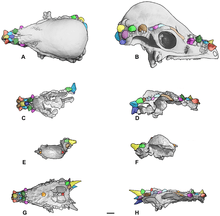

Dracorex and Stygimoloch were first supposed to be either juvenile or female Pachycephalosaurus at the 2007 annual meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.[20] Jack Horner of Montana State University presented evidence, from analysis of the skull of the single existing Dracorex specimen, that this dinosaur may well be a juvenile form of Stygimoloch. In addition, he presented data that indicates that both Stygimoloch and Dracorex may be juvenile forms of Pachycephalosaurus. Horner and M.B. Goodwin published their findings in 2009, showing that the spike/node and skull dome bones of all three 'species' exhibit extreme plasticity, and that both Dracorex and Stygimoloch are known only from juvenile specimens while Pachycephalosaurus is known only from adult specimens. These observations, in addition to the fact that all three forms lived in the same time and place, led them to conclude that Dracorex and Stygimoloch were simply juvenile Pachycephalosaurus, which lost spikes and grew domes as they aged.[21] A 2010 study by Nick Longrich and colleagues also supported the hypothesis that all flat-skulled pachycephalosaur species were juveniles of the dome-headed adults, such as Goyocephale and Homalocephale.[22] The discovery of baby skulls assigned to Pachycephalosaurus that were described in 2016 from two different bone beds in the Hell Creek Formation have been presented as further evidence for this hypothesis. The fossils, as described by David Evans and Mark Goodwin et al are identical to all three supposed genera in the placement of the rugose knobs on their skulls, and thus the unique features of Stygimoloch and Dracorex are instead morphologically consistent features on a Pachycephalosaurus growth curve.[3]

Dome function

It has been commonly hypothesized that Pachycephalosaurus and its relatives were the bipedal equivalents of bighorn sheep or musk oxen, where male individuals would ram each other headlong, and that they would horizontally straighten their head, neck, and body in order to transmit stress during ramming. However, there have also been alternative suggestions that the pachycephalosaurs could not have used their domes in this way.

The primary argument that has been raised against head-butting is that the skull roof may not have adequately sustained impact associated with ramming, as well as a lack of definitive evidence of scars or other damage on fossilized Pachycephalosaurus skulls (however, more recent analyses have uncovered such damage; see below).[23][24] Furthermore, the cervical and anterior dorsal vertebrae show that the neck was carried in an "S"- or "U"-shaped curve, rather than a straight orientation, and thus unfit for transmitting stress from direct head-butting. Lastly, the rounded shape of the skull would lessen the contacted surface area during head-butting, resulting in glancing blows.[15]

Alternatively, Pachycephalosaurus and other pachycephalosaurid genera may have engaged in flank-butting during intraspecific combat. In this scenario, an individual may have stood roughly parallel or faced a rival directly, using intimidation displays to cow its rival. If intimidation failed, the Pachycephalosaurus would bend its head downward and to the side, striking the rival pachycephalosaur on its flank. This hypothesis is supported by the relatively broad torso of most pachycephalosaurs, which would have protected vital organs from trauma. The flank-butting theory was first proposed by Sues in 1978, and expanded upon by Ken Carpenter in 1997.[15]

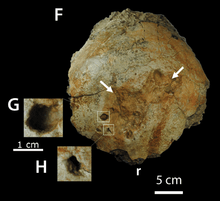

In 2012, a study showed that cranial pathologies in a P. wyomingensis specimen were likely due to agonistic behavior. It was also proposed that similar damage in other pachycephalosaur specimens previously explained as taphonomic artifacts and bone absorptions may instead have been due to such behavior.[24] Peterson et al. (2013) studied cranial pathologies among the Pachycephalosauridae and found that 22% of all domes examined had lesions that are consistent with osteomyelitis, an infection of the bone resulting from penetrating trauma, or trauma to the tissue overlying the skull leading to an infection of the bone tissue. This high rate of pathology lends more support to the hypothesis that pachycephalosaurid domes were employed in intra-specific combat.[25] Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis specimen BMR P2001.4.5 was observed to have 23 lesions in its frontal bone and P. wyomingensis specimen DMNS 469 was observed to have 5 lesions. The frequency of trauma was comparable across the different genera in the pachycephalosaurid family, despite the fact that these genera vary with respect to the size and architecture of their domes, and fact that they existed during varying geologic periods.[25] These findings were in stark contrast with the results from analysis of the relatively flat-headed pachycephalosaurids, where there was an absence of pathology. This would support the hypothesis that these individuals represent either females or juveniles,[26] where intra-specific combat behavior is not expected.

Histological examination reveals that pachycephalosaurid domes are composed of a unique form of fibrolamellar bone[27] which contains fibroblasts that play a critical role in wound healing, and are capable of rapidly depositing bone during remodeling.[28] Peterson et al. (2013) concluded that taken together, the frequency of lesion distribution and the bone structure of frontoparietal domes, lends strong support to the hypothesis that pachycephalosaurids used their unique cranial structures for agonistic behavior.[25] CT scan comparisons of the skulls of Stegoceras validum, Prenocephale prenes, and several head-striking artiodactyls have also supported pachycephalosaurids as being well-equipped for head-butting.[29]

Diet

Scientists do not yet know what these dinosaurs ate. Having very small, ridged teeth, they could not have chewed tough, fibrous plants as effectively as other dinosaurs of the same period. It is assumed that pachycephalosaurs lived on a mixed diet of leaves, seeds, and fruits. The sharp, serrated teeth would have been very effective for shredding plants.[30] It is also suspected that the dinosaur may have included meat in its diet. The most complete fossil jaw shows that it had serrated blade-like front teeth, reminiscent of those of carnivorous theropods.[31]

Paleoecology

Nearly all Pachycephalosaurus fossils have been recovered from the Lance Formation and Hell Creek Formation of the western United States.[8] Pachycephalosaurus possibly co-existed alongside additional pachycephalosaur species of the genera Sphaerotholus, as well as Dracorex and Stygimoloch, though these last two genera may represent juveniles of Pachycephalosaurus itself.[21] Other dinosaurs that shared its time and place include Thescelosaurus, the hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus and a possible species of Parasaurolophus, ceratopsids like Triceratops, Torosaurus, Nedoceratops, Tatankaceratops and Leptoceratops, ankylosaurids Ankylosaurus, nodosaurids Denversaurus and Edmontonia, and the theropods Acheroraptor, Dakotaraptor, Ornithomimus, Struthiomimus, Anzu, Leptorhynchos, Pectinodon, Paronychodon, Richardoestesia and Tyrannosaurus.[32]

References

- "Definition of pachycephalosaurus | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- Horner, J. R.; Goodwin, M. B. (2009). Sereno, Paul (ed.). "Extreme Cranial Ontogeny in the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Pachycephalosaurus". PLOS ONE. 4 (10): e7626. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7626H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007626. PMC 2762616. PMID 19859556.

- Goodwin, Mark B.; Evans, David C. (2016). "The early expression of squamosal horns and parietal ornamentation confirmed by new end-stage juvenile Pachycephalosaurus fossils from the Upper Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation, Montana". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (2): e1078343. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1078343. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Baird, Donald (1979). "The dome-headed dinosaur Tylosteus ornatus Leidy 1872 (Reptilia: Ornithischia: Pachycephalosauridae)". Notulae Naturae. 456: 1–11.

- Leidy, Joseph (1872). "Remarks on some extinct vertebrates". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia: 38–40.

- ICZN Opinion 1371, "Pachycephalosaurus Brown & Schlaikjer, 1943 and Troodon wyomingensis Gilmore, 1931 (Reptilia, Dinosauria): Conserved." Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 43 (1): April 1986.

- Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Pachycephalosaurus". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 664–668. ISBN 978-0-89950-917-4.

- Sullivan, Robert M. (2006). "A taxonomic review of the Pachycephalosauridae (Dinosauria:Ornithischia)" (PDF). Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 35: 347–366. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- Stokstad, Erik (2007). "SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY MEETING: Did Horny Young Dinosaurs Cause Illusion of Separate Species?". Science. 318 (5854): 1236. doi:10.1126/science.318.5854.1236. PMID 18033861.

- Gilmore, Charles W. (1931). "A new species of troodont dinosaur from the Lance Formation of Wyoming" (PDF). Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 79 (9): 1–6. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.79-2875.1.

- Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Troodon". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 933–938. ISBN 978-0-89950-917-4.

- Brown, Barnum; Schlaikjer, Erich M. (1943). "A study of the troödont dinosaurs with the description of a new genus and four new species" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 82 (5): 115–150.

- Galton, Peter M.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (1983). "New data on pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs (Reptilia: Ornithischia) from North America". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 20 (3): 462–472. Bibcode:1983CaJES..20..462G. doi:10.1139/e83-043.

- Evans, D. C.; Vavrek, M. J.; Larsson, H. C. E. (2015). "Pachycephalosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) cranial remains from the latest Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Scollard Formation of Alberta, Canada". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 95: 579–585. doi:10.1007/s12549-015-0188-x. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- Carpenter, Kenneth (1 December 1997). "Agonistic behavior in pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia: Dinosauria): a new look at head-butting behavior" (pdf). Contributions to Geology. 32 (1): 19–25.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- Organ, Christopher O.; Adams, Jason (2005). "The histology of ossified tendon in dinosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (3): 602–613. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0602:THOOTI]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-29. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- Pisani, Davide; Yates, Adam M.; Langer, Max C.; Benton, Michael J. (2002). "A genus-level supertree of the Dinosauria". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 269 (1494): 915–921. doi:10.1098/rspb.2001.1942. PMC 1690971. PMID 12028774.

- Evans, D. C.; Schott, R. K.; Larson, D. W.; Brown, C. M.; Ryan, M. J. (2013). "The oldest North American pachycephalosaurid and the hidden diversity of small-bodied ornithischian dinosaurs". Nature Communications. 4: 1828. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1828E. doi:10.1038/ncomms2749. PMID 23652016.

- Erik Stokstad,"SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY MEETING: Did Horny Young Dinosaurs Cause Illusion of Separate Species?", Science Vol. 18, 23 Nov. 2007, p. 1236; http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/318/5854/1236

- Horner J.R. and Goodwin, M.B. (2009). "Extreme cranial ontogeny in the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Pachycephalosaurus." PLoS ONE, 4(10): e7626. Online full text

- Longrich, N.R.; Sankey, J.; Tanke, D. (2010). "Texacephale langstoni, a new genus of pachycephalosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the upper Campanian Aguja Formation, southern Texas, USA". Cretaceous Research. 31: 274–284. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.12.002.

- Goodwin, Mark; Horner, John R. (2004). "Cranial histology of pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia: Marginocephalia) reveals transitory structures inconsistent with head-butting behavior". Paleobiology. 30 (2): 253–267. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0253:CHOPOM>2.0.CO;2.

- Peterson, J. E.; Vittore, C. P. (2012). Farke, Andrew A (ed.). "Cranial Pathologies in a Specimen of Pachycephalosaurus". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e36227. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736227P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036227. PMC 3340332. PMID 22558394.

- Peterson, JE; Dischler, C; Longrich, NR (2013). "Distributions of Cranial Pathologies Provide Evidence for Head-Butting in Dome-Headed Dinosaurs (Pachycephalosauridae)". PLoS ONE. 8 (7): e68620. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...868620P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068620. PMC 3712952. PMID 23874691.

- Longrich, NR; Sankey, J; Tanke, D (2010). "Texacephale langstoni, a new genus of pachycephalosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the upper Campanian Aguja Formation, southern Texas, USA". Cretaceous Research. 31 (2): 274–284. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.12.002.

- eid REH (1997) Histology of bones and teeth. In: Currie, PJ and Padian, K, editors. Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. 329–339.

- Horner JR, Goodwin MB (2009) Extreme Cranial Ontogeny in the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Pachycephalosaurus PLoS ONE 4(10): e7626. Available: http://www.plosone.org/article/inf o%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone. 0007626. Accessed 2012 Dec 4.

- Snively, E; Theodor, JM (2011). "Common Functional Correlates of Head-Strike Behavior in the Pachycephalosaur Stegoceras validum (Ornithischia, Dinosauria) and Combative Artiodactyls". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e21422. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621422S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021422. PMC 3125168. PMID 21738658.

- Maryańska, Teresa; Chapman, Ralph E.; Weishampel, David B. (2004). "Pachycephalosauria". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 464–477. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- "Vegetarian dinosaur may have actually eaten meat, skull suggests". Science & Innovation. 2018-10-24. Retrieved 2019-05-07.

- Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loeuff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth, M.P.; and Noto, Christopher R. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution". In: D.B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmólska (eds.) The Dinosauria (2nd edition). 517–606. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

External links

- Pachycephalosaurus in the Dinodictionary

- Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis from National Geographic Online

- TEDx talk by Jack Horner on shape-shifting dinosaur skulls and dinosaur misclassification.