Pachycephalosauria

Pachycephalosauria (/ˌpækɪsɛfələˈsɔːriə, -ˌkɛf-/;[1] from Greek παχυκεφαλόσαυρος for 'thick headed lizards') is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs. Along with Ceratopsia, it makes up the clade Marginocephalia. Genera include Pachycephalosaurus, Stegoceras, and Prenocephale. With the exception of two species, most pachycephalosaurs lived during the Late Cretaceous Period, dating between about 85.8 and 65.5 million years ago. They lived around the same time as T. rex. [2] They are exclusive to the Northern Hemisphere, all of them being found in North America and Asia. They were all bipedal, herbivorous/omnivorous animals with thick skulls. Skulls can be domed, flat, or wedge-shaped depending on the species, and are all heavily ossified. The domes were often surrounded by nodes and/or spikes. Partial skeletons have been found of several pachycephalosaur species, but to date no complete skeletons have been discovered. Often isolated skull fragments are the only bones that are found.[3]

| Pachycephalosaurs | |

|---|---|

| Cast of a Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis skull, Oxford University Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Cerapoda |

| Clade: | †Marginocephalia |

| Suborder: | †Pachycephalosauria Maryańska & Osmólska, 1974 |

| Family: | †Pachycephalosauridae Sternberg, 1945 (conserved name) |

| Type species | |

| †Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis Gilmore, 1931 (conserved name) | |

| Genera | |

| |

Candidates for the earliest known pachycephalosaur include Ferganocephale adenticulatum from Middle Jurassic Period strata of Kyrgyzstan and Stenopelix valdensis from Early Cretaceous strata of Germany, although R.M. Sullivan has doubted that either of these species are pachycephalosaurs.[2] In 2017, a phylogenetic analysis conducted by Han and colleagues identified Stenopelix as a member of the Ceratopsia.[4]

Paleobiology

Anatomy

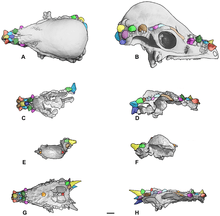

Pachycephalosaurs were bipedal ornithischians characterized by their thickened skulls. They had a bulky torso with an expanded gut cavity and broad hips, short forelimbs, long legs, a short, thick neck, and a heavy tail. Large orbits and a large optic nerve point to pachycephalosaurs having good vision, and uncharacteristically large olfactory lobes indicate that they had a good sense of smell relative to other dinosaurs.[3] They were fairly small dinosaurs, with most falling in the range of 2–3 meters (6.6-9.8 feet) in length and the largest, Pachycephalosaurus wyomingensis, estimated to measure 4.5 meters (14.8 feet) long and weigh 450 kilograms (990 pounds).[2][5] The characteristic skull of pachycephalosaurs is a result of the fusion and thickening of the frontals and parietals, accompanied by the closing of the supratemporal fenestra. In some species this takes the form of a raised dome; in others, the skull is flat or wedge-shaped. While the flat-headed pachycephalosaurs are traditionally regarded as distinct species or even families, they may represent juveniles of dome-headed adults.[2][3] All display highly ornamented jugals, squamosals, and postorbitals in the form of blunt horns and nodes. Many species are only known from skull fragments, and a complete pachycephalosaur skeleton is yet to be found.[3]

Head-butting behavior

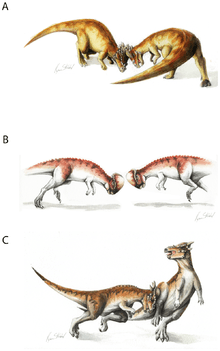

The adaptive significance of the skull dome has been heavily debated. The popular hypothesis among the general public that the skull was used in head-butting, as sort of a dinosaurian battering ram, was first proposed by Colbert 1955. This view was popularized in the 1956 science fiction story "A Gun for Dinosaur" by L. Sprague de Camp. Many paleontologists have since argued for the head-butting hypothesis, including Galton 1970 and Sues 1978. In this hypothesis, pachycephalosaurs rammed each other head-on, as do modern-day mountain goats and musk oxen.

Anatomical evidence for combative behavior includes vertebral articulations providing spinal rigidity, and the shape of the back indicating strong neck musculature.[6] It has been suggested that a pachycephalosaur could make its head, neck, and body horizontally straight, in order to transmit stress during ramming. However, in no known dinosaur could the head, neck, and body be oriented in such a position. Instead, the cervical and anterior dorsal vertebrae of pachycephalosaurs show that the neck was carried in an "S"- or "U"-shaped curve.[7]

Also, the rounded shape of the skull would lessen the contacted surface area during head-butting, resulting in glancing blows. Other possibilities include flank-butting, defense against predators, or both. The relatively wide build of pachycephalosaurs (which would protect vital internal organs from harm during flank-butting) and the squamosal horns of the Stygimoloch (which would have been used to great effect during flank-butting) add credence to the flank-butting hypothesis.

A histological study conducted by Goodwin & Horner 2004 argued against the battering ram hypothesis. They argued that the dome was "an ephemeral ontogenetic stage", the spongy bone structure could not sustain the blows of combat, and the radial pattern was simply an effect of rapid growth.[8] Later biomechanical analyses by Snively & Cox 2008 and Snively & Theodor 2011 concluded, however, that the domes could withstand combat stresses.[6] Lehman 2010 argued that the growth patterns discussed by Goodwin and Horner are not inconsistent with head-butting behavior.[9]

Goodwin & Horner 2004 instead argued that the dome functioned for species recognition. There is evidence that the dome had some form of external covering, and it is reasonable to consider the dome may have been brightly covered, or subject to change color seasonally.[8] Due to the nature of the fossil record, however, it cannot be observed whether or not color played a role in dome function.

Longrich, Sankey & Tanke 2010 argued that species recognition is an unlikely evolutionary cause for the dome, because dome forms are not notably different between species. Because of this general similarity, several genera of Pachycephalosauridae have sometimes been incorrectly lumped together. This is unlike the case in ceratopsians and hadrosaurids, which had much more distinct cranial ornamentation. Longrich et al argued that instead the dome had a mechanical function, such as combat, one which was important enough to justify the resource investment.[10]

Support for head-butting by paleopathology

Peterson et al (2013) studied cranial pathologies among the Pachycephalosauridae and found that 22% of all domes examined had lesions that are consistent with osteomyelitis, an infection of the bone resulting from penetrating trauma, or trauma to the tissue overlying the skull leading to an infection of the bone tissue. This high rate of pathology lends more support to the hypothesis that pachycephalosaurid domes were employed in intra-specific combat.[11] The frequency of trauma was comparable across the different genera in this family, despite the fact that these genera vary with respect to the size and architecture of their domes, and fact that they existed during varying geologic periods.[11] These findings were in stark contrast with the results from analysis of the relatively flat-headed pachycephalosaurids, where there was an absence of pathology. This would support the hypothesis that these individuals represent either females or juveniles,[12] where intra-specific combat behavior is not expected.

Histological examination reveals that pachycephalosaurid domes are composed of a unique form of fibrolamellar bone[13] which contains fibroblasts that play a critical role in wound healing, and are capable of rapidly depositing bone during remodeling.[14] Peterson et al (2013) concluded that, taken together, the frequency of lesion distribution and the bone structure of frontoparietal domes lend strong support to the hypothesis that pachycephalosaurids used their unique cranial structures for agonistic behavior.[11]

Diet

The small size of most pachycephalosaur species and lack of skeletal adaptation indicates that they were not climbers and primarily ate food close to the ground. Mallon et al. (2013) examined herbivore coexistence on the island continent of Laramidia, during the Late Cretaceous and concluded that pachycephalosaurids were generally restricted to feeding on vegetation at, or below, the height of 1 meter.[15] They exhibit heterodonty, having different tooth morphology between the premaxillary teeth and maxillary teeth. Front teeth are small and peg-like with an ovular cross section and were most likely used for grabbing food. In some species, the last premaxillary tooth was enlarged and canine-like. Back teeth are small and triangular with denticles on the front and back of the crown, used for mouth processing. In species in which the dentary has been found, mandibular teeth are similar in size and shape to those in the upper jaw. Wear patterns on the teeth vary by species, indicating a range of food preferences which could include seeds, stems, leaves, fruits, and possibly insects. A very wide rib cage and large gut cavity extending all the way to the base of the tail suggests the use of fermentation to digest food.[3]

Biogeography

Distribution

Pachycephalosaurs lived exclusively in Laurasia, being found in western North America and central Asia. Pachycephalosaurs originated in Asia and had two major dispersal events, resulting in the two separate waves of pachycephalosaur evolution observed in Asia. The first, occurring before the late Santonian or early Campanian, involved a migration from Asia to North America, most likely by way of the Bering Land Bridge. This migration was by a common ancestor of Stygimoloch, Stegoceras, Tylocephale, Prenocephale, and Pachycephalosaurus. The second event occurred before the middle Campanian, and involved a migration back into Asia from North America by a common ancestor of Prenocephale and Tylocephale. Two species originally reported to be pachycephalosaurs discovered outside this range, Yaverlandia bitholus of England and Majungatholus atopus of Madagascar, have recently been shown to actually be theropods.[3][16]

Environment

The Asian and North American species of pachycephalosaurs lived in markedly different environments. Asian specimens are normally more intact, indicating they were not transported far from their place of death before fossilization. They likely lived in a large desert region in central Asia with a hot and arid climate. North American specimens are typically found in rocks that were formed by erosion from the Rocky Mountains. Specimens are far less intact; usually only skull caps are recovered, and those found regularly exhibit surface exfoliation and other signs that they were transported long distances by water before fossilization. It is assumed that they lived in the mountains in a temperate climate and were carried by erosion after death to their final resting place.[17]

Classification

Most pachycephalosaurid remains are not complete, usually consisting of portions of the frontoparietal bone that forms the distinctive dome. This can make taxonomic identification a difficult task, as the classification of genera and species within Pachycephalosauria relies almost entirely on cranial characteristics. Consequently, improper species have historically been appointed to the clade. For instance, Majungatholus, once thought to be a pachycephalosaur, is now recognized as a specimen of the abelisaurid theropod Majungasaurus, and Yaverlandia, another dinosaur initially described as a pachycephalosaurid, has also recently been reclassified as a coelurosaur (Naish in Sullivan 2006). Further complicating matters are the diverse interpretations of ontogenetic and sexual features in pachycephalosaurs.

A 2009 paper proposed that Dracorex and Stygimoloch were just early growth stages of Pachycephalosaurus, rather than distinct genera.[18]

A reworking of Cerapoda finds the members of Heterodontosauridae are basal representatives of Pachycephalosauria.[19]

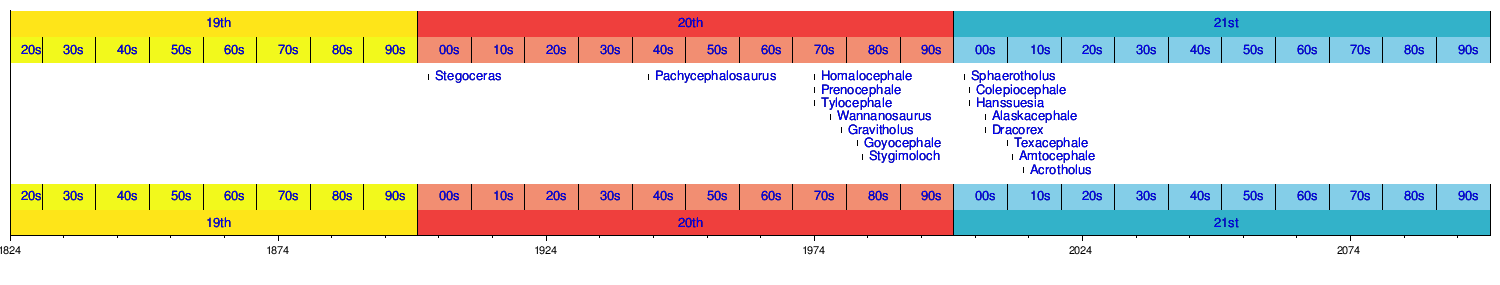

Taxonomy

The Pachycephalosauria was first named as a suborder of the order Ornithischia by Maryańska & Osmólska 1974. They included within it only one family, the Pachycephalosauridae.[20] Later researchers, such as Michael Benton, have ranked it as an infraorder of a suborder Cerapoda, which unites the ceratopsians and ornithopods.[21] In 2006, Robert Sullivan published a re-evaluation of pachycephalosaur taxonomy. Sullivan considered attempts by Maryańska and Osmólska to restrict the definition of Pachycephalosauria redundant with their Pachycephalosauridae, since they were diagnosed by the same anatomical characters. Sullivan also rejected attempts by Sereno 1986, in his phylogenetic studies,[22] to re-define Pachycephalosauridae to include only "dome-skulled" species (including Stegoceras and Pachycephalosaurus), while leaving more "basal" species outside that family in Pachycephalosauria. Therefore, Sullivan's use of Pachycephalosauridae is equivalent to Sereno and Benton's use of Pachycephalosauria.

Sullivan diagnosed the Pachycephalosauridae-based only on characters of the skull, with the defining character being a dome-shaped frontoparietal skull bone. According to Sullivan, the absence of this feature in some species assumed to be primitive led to the split in classification between domed and non-domed pachycephalosaurs; however, discovery of more advanced and possibly juvenile pachycephalosaurs with flat skulls (such as Dracorex hogwartsia) show this distinction to be incorrect. Sullivan also pointed out that the original diagnosis of Pachycephalosauridae centered around "flat to dome-like" skulls, so the flat-headed forms should be included in the family.[23]

Phylogeny

The cladogram presented here follows an analysis by Williamson & Carr 2002.[24]

| Pachycephalosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cladogram after Longrich, Sankey and Tanke (2010).[25]

| Pachycephalosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Below is a cladogram modified from Evans et al., 2013.[26]

| Pachycephalosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- "Pachycephalosauria". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages (PDF).

- Maryanska, T.; Chapman, R.E.; Weishampel, D.B. (2004). "Pachycephalosauria". In 2nd (ed.). The Dinosauria. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 464–477. ISBN 978-0520242098. OCLC 493366196.

- Han, F.-L.; Forster, C.A.; Clark, J.M.; Xu, X. (2016). "Cranial anatomy of Yinlong downsi (Ornithischia: Ceratopsia) from the Upper Jurassic Shishugou Formation of Xinjiang, China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (1): e1029579. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1029579.

- S., Paul, Gregory (2010). The Princeton field guide to dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691137209. OCLC 930852339.

- Snively & Cox 2008

- Carpenter 1997

- Goodwin & Horner 2004

- Lehman 2010

- Longrich, Sankey & Tanke 2010

- Peterson, JE; Dischler, C; Longrich, NR (2013). "Distributions of Cranial Pathologies Provide Evidence for Head-Butting in Dome-Headed Dinosaurs (Pachycephalosauridae)". PLoS ONE. 8 (7): e68620. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...868620P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0068620. PMC 3712952. PMID 23874691.

- Longrich, NR; Sankey, J; Tanke, D (2010). "Texacephale langstoni, a new genus of pachycephalosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the upper Campanian Aguja Formation, southern Texas, USA". Cretaceous Research. 31 (2): 274–284. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.12.002.

- Reid REH (1997) "Histology of bones and teeth." In: Currie, PJ and Padian, K, editors. Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. 329–339.

- Horner, JR; Goodwin, MB (2009). "Extreme Cranial Ontogeny in the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Pachycephalosaurus". PLoS ONE. 4 (10): e7626. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7626H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007626. PMC 2762616. PMID 19859556.

- Mallon, Jordan C; David C Evans; Michael J Ryan; Jason S Anderson (2013). "Feeding height stratification among the herbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada". BMC Ecology. 13: 14. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-13-14. PMC 3637170. PMID 23557203.

- NAISH, D.; MARTILL, D. M. (2008). "Dinosaurs of Great Britain and the role of the Geological Society of London in their discovery: Ornithischia". Journal of the Geological Society. 165 (3): 613–623. Bibcode:2008JGSoc.165..613N. doi:10.1144/0016-76492007-154.

- Weishampel, David B. (2009). Dinosaurs : a concise natural history. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511479410. OCLC 476234422.

- Horner & Goodwin 2009

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08912963.2020.1793979

- Maryańska & Osmólska 1974

- Benton 2004, pp. 472

- Sereno 1986

- Sullivan 2006

- Williamson & Carr 2002

- Longrich, N.R., Sankey, J., and Tanke, D. (2010). "Texacephale langstoni, a new genus of pachycephalosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the upper Campanian Aguja Formation, southern Texas, USA". Cretaceous Research. 31 (2): 274–284. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.12.002.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Evans, D. C.; Schott, R. K.; Larson, D. W.; Brown, C. M.; Ryan, M. J. (2013). "The oldest North American pachycephalosaurid and the hidden diversity of small-bodied ornithischian dinosaurs". Nature Communications. 4: 1828. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.1828E. doi:10.1038/ncomms2749. PMID 23652016.

References

- Benton, Michael J (2004). Vertebrate Palaeontology (3rd ed.). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-632-05637-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carpenter, Kenneth (1997). "Agonistic behavior in pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia:Dinosauria): a new look at head-butting behavior" (PDF). Contributions to Geology. 32 (1): 19–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2011-07-16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colbert, Edwin (1955). Evolution of the Vertebrates. New York: John wiley.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Galton, P (1970). "Pachycephalosaurids — dinosaurian battering rams". Discovery. 6: 23–32.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodwin, MB; Horner, JR (June 2004). "Cranial histology of pachycephalosaurs (Ornithischia: Marginocephalia) reveals transitory structures inconsistent with head-butting behavior". Paleobiology. 30 (2): 253–267. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0253:CHOPOM>2.0.CO;2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horner, JR; Goodwin, MB (2009). Sereno, Paul (ed.). "Extreme Cranial Ontogeny in the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Pachycephalosaurus". PLoS ONE. 4 (10): e7626. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7626H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007626. PMC 2762616. PMID 19859556.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lehman, TM (2010). "Pachycephalosauridae from the San Carlos and Aguja Formations (Upper Cretaceous) of west Texas, and observations of the frontoparietal dome". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (3): 786–798. doi:10.1080/02724631003763532. ISSN 0272-4634.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Longrich, NR; Sankey, J; Tanke, D (2010). "Texacephale langstoni, a new genus of pachycephalosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the upper Campanian Aguja Formation, southern Texas, USA". Cretaceous Research. 31 (2): 274–284. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.12.002.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maryańska, T; Osmólska, H (1974). "Pachycephalosauria, a new suborder of ornithischian dinosaurs". Palaeontologica Polonica (30): 45–102.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sereno, PC (1986). "Phylogeny of the bird-hipped dinosaurs (Order Ornithischia)". National Geographic Research. 2: 234–256.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snively, E; Cox, A (2008). "Structural mechanics of pachycephalosaur crania permitted head-butting behavior". Palaeontologia Electronica (11).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snively, E; Theodor, JM (2011). Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). "Common Functional Correlates of Head-Strike Behavior in the Pachycephalosaur Stegoceras validum (Ornithischia, Dinosauria) and Combative Artiodactyls". PLoS ONE. 6 (6): e21422. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621422S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021422. PMC 3125168. PMID 21738658.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stokstad, Erik (November 2007). "Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Meeting: Did Horny Young Dinosaurs Cause Illusion of Separate Species?". Science. 318 (5854): 1236. doi:10.1126/science.318.5854.1236. PMID 18033861.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sues, H-D (1978). "Functional morphology of the dome in pachycephalosaurid dinosaurs". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie: 459–472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sullivan, RM (2006). "A taxonomic review of the Pachycephalosauridae (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin (35): 347–365.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Watabe, Mahito; Tsogtbaatar, Khishigjaw; Sullivan, Robert M. (2011). "A new pachycephalosaurid from the Baynshire Formation (Cenomanian-late Santonian), Gobi Desert, Mongolia" (PDF). Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin. 53: 489–497.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williamson, TE; Carr, TD (2002). "A new genus of derived pachycephalosaurian from western North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (4): 779–801. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0779:ANGODP]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)