Ceratopsia

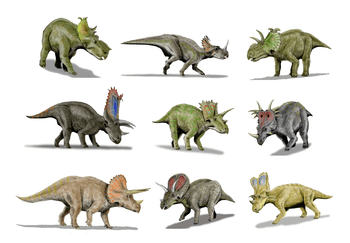

Ceratopsia or Ceratopia (/ˌsɛrəˈtɒpsiə/ or /ˌsɛrəˈtoʊpiə/; Greek: "horned faces") is a group of herbivorous, beaked dinosaurs that thrived in what are now North America, Europe, and Asia, during the Cretaceous Period, although ancestral forms lived earlier, in the Jurassic. The earliest known ceratopsian, Yinlong downsi, lived between 161.2 and 155.7 million years ago.[3] The last ceratopsian species, Triceratops prorsus, became extinct during the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, 66 million years ago.[3]

| Ceratopsians | |

|---|---|

| |

| Triceratops skeleton, Smithsonian Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Marginocephalia |

| Suborder: | †Ceratopsia Marsh, 1890 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Early members of the ceratopsian group, such as Psittacosaurus, were small bipedal animals. Later members, including ceratopsids like Centrosaurus and Triceratops, became very large quadrupeds and developed elaborate facial horns and frills extending over the neck. While these frills might have served to protect the vulnerable neck from predators, they may also have been used for display, thermoregulation, the attachment of large neck and chewing muscles or some combination of the above. Ceratopsians ranged in size from 1 meter (3 ft) and 23 kilograms (50 lb) to over 9 meters (30 ft) and 9,100 kg (20,100 lb).

Triceratops is by far the best-known ceratopsian to the general public. It is traditional for ceratopsian genus names to end in "-ceratops", although this is not always the case. One of the first named genera was Ceratops itself, which lent its name to the group, although it is considered a nomen dubium today as its fossil remains have no distinguishing characteristics that are not also found in other ceratopsians.[4]

Anatomy

Ceratopsians are easily recognized by features of the skull. On the tip of a ceratopsian upper jaw is the rostral bone, an edentulous (toothless) ossification, unique to ceratopsians. Othniel Charles Marsh recognized and named this bone, which acts as a mirror image of the predentary bone on the lower jaw. This ossification evolved to morphologically aid the mastication of plant matter.[5] Along with the predentary bone, which forms the tip of the lower jaw in all ornithischians, the rostral forms a superficially parrot-like beak. Also, the jugal bones below the eye are prominent, flaring out sideways to make the skull appear somewhat triangular when viewed from above. This triangular appearance is accentuated in later ceratopsians by the rearwards extension of the parietal and squamosal bones of the skull roof, to form the neck frill.[6][7]

The epoccipital is a distinctive bone found lining the frills of ceratopsians. The name is a misnomer, as they are not associated with the occipital bone.[8] Epoccipitals begin as separate bones that fuse during the animal's growth to either the squamosal or parietal bones that make up the base of the frill. These bones were ornamental instead of functional, and may have helped differentiate species. Epoccipitals probably were present in all known ceratopsids with the possible exception of Zuniceratops.[9] They appear to have been broadly different between short-frilled ceratopsids (centrosaurines) and long-frilled ceratopsids (chasmosaurines), being elliptical with constricted bases in the former group, and triangular with wide bases in the latter group. Within these broad definitions, different species would have somewhat different shapes and numbers. In centrosaurines especially, like Centrosaurus, Pachyrhinosaurus, and Styracosaurus, these bones become long and spike- or hook-like.[10] A well-known example is the coarse sawtooth fringe of broad triangular epoccipitals on the frill of Triceratops. When regarding the ossification's morphogenetic traits, it can be described as dermal. The term epoccipital was coined by famous paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1889.[8][11]

History of study

The first ceratopsian remains known to science were discovered during the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories led by the American geologist F.V. Hayden. Teeth discovered during an 1855 expedition to Montana were first assigned to hadrosaurids and included within the genus Trachodon. It was not until the early 20th century that some of these were recognized as ceratopsian teeth.[12] During another of Hayden's expeditions in 1872, Fielding Bradford Meek found several giant bones protruding from a hillside in southwestern Wyoming. He alerted paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope, who led a dig to recover the partial skeleton. Cope recognized the remains as a dinosaur, but noted that even though the fossil lacked a skull, it was different from any type of dinosaur then known. He named the new species Agathaumas sylvestris, meaning "marvellous forest-dweller".[13] Soon after, Cope named two more dinosaurs that would eventually come to be recognized as ceratopsids: Polyonax and Monoclonius. Monoclonius was notable for the number of disassociated remains found, including the first evidence of ceratopsid horns and frills. Several Monoclonius fossils were found by Cope, assisted by Charles Hazelius Sternberg, in summer 1876 near the Judith River in Chouteau County, Montana. Since the ceratopsians had not been recognised yet as a distinctive group, Cope was uncertain about much of the fossil material, not recognizing the nasal horn core, nor the brow horns, as part of a fossil horn. The frill bone was interpreted as a part of the breastbone.[14]

In 1888 and 1889, Othniel Charles Marsh described the first well preserved horned dinosaurs, Ceratops and Triceratops. In 1890 Marsh classified them together in the family Ceratopsidae and the order Ceratopsia. This prompted Cope to reexamine his own specimens and to realize that Triceratops, Monoclonius, and Agathaumas all represented a single group of similar dinosaurs, which he named Agathaumidae in 1891. Cope redescribed Monoclonius as a horned dinosaur, with a large nasal horn and two smaller horns over the eyes, and a large frill.

Classification

Ceratopsia was coined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1890 to include dinosaurs possessing certain characteristic features, including horns, a rostral bone, teeth with two roots, fused neck vertebrae, and a forward-oriented pubis. Marsh considered the group distinct enough to warrant its own suborder within Ornithischia.[15] The name is derived from the Greek κέρας/kéras meaning 'horn' and ὄψῐς/ópsis meaning 'appearance, view' and by extension 'face'. As early as the 1960s, it was noted that the name Ceratopsia is actually incorrect linguistically and that it should be Ceratopia.[16] However, this spelling, while technically correct, has been used only rarely in the scientific literature, and the vast majority of paleontologists continue to use Ceratopsia. As the ICZN does not govern taxa above the level of superfamily, this is unlikely to change.

Taxonomy

Following Marsh, Ceratopsia has usually been classified as a suborder within the order Ornithischia. While ranked taxonomy has largely fallen out of favor among dinosaur paleontologists, some researchers have continued to employ such a classification, though sources have differed on what its rank should be. Most who still employ the use of ranks have retained its traditional ranking of suborder,[17] though some have reduced to the level of infraorder.[18]

Possible ceratopsians from the Southern Hemisphere include the Australian Serendipaceratops, known from an ulna, and Notoceratops from Argentina is known from a single toothless jaw (which has been lost).[19] Craspedodon from the Late Cretaceous (Santonian) of Belgium may also be a ceratopsian, specifically a neoceratopsian closer to ceratopsoidea than protoceratopsidae.[20] Possible leptoceratopsid remains have also been described from the early Campanian of Sweden.[21]

Phylogeny

In clade-based phylogenetic taxonomy, Ceratopsia is often defined to include all marginocephalians more closely related to Triceratops than to Pachycephalosaurus.[22] Under this definition, the most basal known ceratopsians are Yinlong, from the Late Jurassic Period, along with Chaoyangsaurus and the family Psittacosauridae, from the Early Cretaceous Period, all of which were discovered in northern China or Mongolia. The rostral bone and flared jugals are already present in all of these forms, indicating that even earlier ceratopsians remain to be discovered.

The clade Neoceratopsia includes all ceratopsians more derived than psittacosaurids. Another subset of neoceratopsians is called Coronosauria, which either includes all ceratopsians more derived than Auroraceratops, or more derived than Leptoceratopsidae. Coronosaurs show the first development of the neck frill and the fusion of the first several neck vertebrae to support the increasingly heavy head. Within Coronosauria, three groups are generally recognized, although the membership of these groups varies somewhat from study to study and some animals may not fit in any of them. One group can be called Protoceratopsidae and includes Protoceratops and its closest relatives, all Asian. Another group, Leptoceratopsidae, includes mostly North American animals that are more closely related to Leptoceratops. The Ceratopsoidea includes animals like Zuniceratops, which are more closely related to the family Ceratopsidae. This last family includes Triceratops and all the large North American ceratopsians and is further divided into the subfamilies Centrosaurinae and Ceratopsinae (also known as Chasmosaurinae).

You Hailu of Beijing's Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, was a co-author with Xu and Makovicky in 2002 but, in 2003, he and Peter Dodson from the University of Pennsylvania published a separate analysis.[23] The two presented this analysis again in 2004.[6] In 2005, You and three others, including Dodson, published on Auroraceratops and inserted this new dinosaur into their phylogeny.[24] In contrast to the previous analysis, You and Dodson find Chaoyangsaurus to be the most basal neoceratopsian, more derived than Psittacosaurus, while Leptoceratopsidae, not Protoceratopsidae, is recovered as the sister group of Ceratopsidae. This study includes Auroraceratops, but lacks seven taxa found in Xu and Makovicky's work, so it is unclear how comparable the two studies are. Asiaceratops and Turanoceratops are each considered nomina dubia and not included.

Xu Xing of the Chinese Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, along with Peter Makovicky, formerly of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City and others, published a cladistic analysis in the 2002 description of Liaoceratops.[25] This analysis is very similar to one published by Makovicky in 2001.[26] Xu and other colleagues added Yinlong to this analysis in 2006.[27]

Brenda Chinnery, formerly of the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana, independently described Prenoceratops in 2005 and published a new phylogeny.[28] In 2006, Makovicky and Mark Norell of the AMNH incorporated Chinnery's analysis into their own and also added Yamaceratops, although they were not able to include Yinlong.[29] Andrew Farke and his colleagues in 2014 published a description of a new neoceratopsian, Aquilops americanus, through the peer-reviewed science journal PLOS ONE. They analysed their taxa as well as most other primitive ceratopsians to get a consensus cladogram. They created their own data matrix and through it found that many groups of ceratopsians could be supported, and that Aquilops was a basal neoceratopsian that could potentially be a protoceratopsid, leptoceratopsid, or ceratopsid, although any one of these groups would have a large ghost lineage with Aquilops. Ajkaceratops was identified as a wildcard taxon that could either place close to Ceratopsoidea or as a very basal neoceratopsian, despite being from the middle Late Cretaceous.[30]

All previously published neoceratopsian phylogenetic analyses were incorporated into the analysis of Eric M. Morschhauser and colleagues in 2019, along with all previously published diagnostic species excluding the incomplete juvenile Archaeoceratops yujingziensis and the problematic genera Bainoceratops, Lamaceratops, Platyceratops and Gobiceratops that are very closely related to and potentially synonymous with Bagaceratops. While there were many unresolved areas of the strict consensus, including all of Leptoceratopsidae, a single most parsimonious tree was found that was most consistent with the relative ages of the taxa included, which is shown below.[31]

| Ceratopsia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Biogeography

Ceratopsia appears to have originated in Asia, as all of the earliest members are found there. Fragmentary remains, including teeth, which appear to be neoceratopsian, are found in North America from the Albian stage (112 to 100 million years ago), indicating that the group had dispersed across what is now the Bering Strait by the middle of the Cretaceous Period.[32] Almost all leptoceratopsids are North American, aside from Udanoceratops, which may represent a separate dispersal event, back into Asia. Ceratopsids and their immediate ancestors, such as Zuniceratops, were unknown outside of western North America, and were presumed endemic to that continent.[6][28] The traditional view that ceratopsoids originated in North America was called into question by the 2009 discovery of better specimens of the dubious Asian form Turanoceratops, which confirmed it as a ceratopsid. It is unknown whether this indicates ceratopsids actually originated in Asia, or if the Turanoceratops immigrated from North America.[33]

Individual variation

Unlike almost all other dinosaur groups, skulls are the most commonly preserved elements of ceratopsian skeletons and many species are known only from skulls. There is a great deal of variation between and even within ceratopsian species. Complete growth series from embryo to adult are known for Psittacosaurus and Protoceratops, allowing the study of ontogenetic variation in these species.[34][35] Significant sexual dimorphism has been noted in Protoceratops and several ceratopsids.[6][7][36]

Ecological role

Psittacosaurus and Protoceratops are the most common dinosaurs in the different Mongolian sediments where they are found.[6] Triceratops fossils are far and away the most common dinosaur remains found in the latest Cretaceous rocks in the western United States, making up as much as 5/6ths of the large dinosaur fauna in some areas.[37] These facts indicate that some ceratopsians were the dominant herbivores in their environments.

Some species of ceratopsians, especially Centrosaurus and its relatives, appear to have been gregarious, living in herds. This is suggested by bonebed finds with the remains of many individuals of different ages.[7] Like modern migratory herds, they would have had a significant effect on their environment, as well as serving as a major food source for predators.

Although ceratopsians are generally considered herbivorous, a few paleontologists, such as Darren Naish and Mark Witton, have speculated online that at least some ceratopsians may have been opportunistically omnivorous.[38][39]

Posture and locomotion

Most restorations of ceratopsians show them with erect hindlimbs but semi-sprawling forelimbs, which suggest that they were not fast movers. But Paul and Christiansen (2000) argued that at least the later ceratopsians had upright forelimbs and the larger species may have been as fast as rhinos, which can run at up to 56 km or 35 miles per hour.[40]

Daily activity patterns

A nocturnal lifestyle has been suggested for the primitive ceratopsian Protoceratops.[41] However, comparisons between the scleral rings of Protoceratops and Psittacosaurus and modern birds and reptiles indicate that they may have been cathemeral, active throughout the day at short intervals.[42]

Paleopathology

Activity-related bone fractures have been documented in ceratopsians.[43] Periostitis has also been documented in the shoulder blade of a ceratopsian.[44]

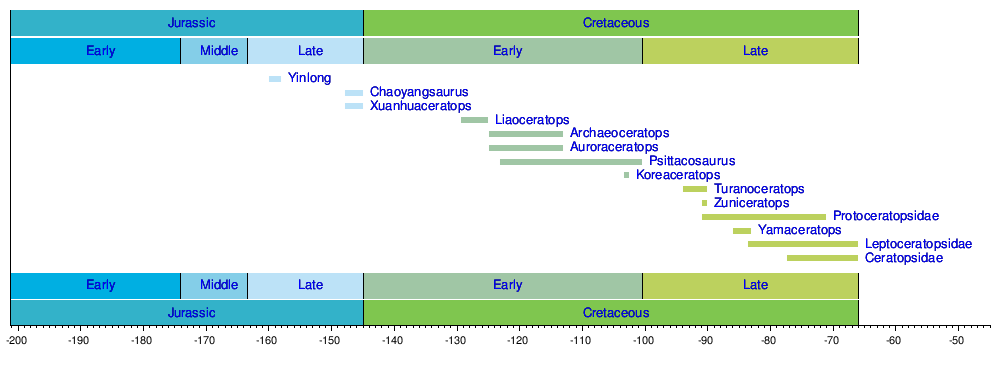

Timeline of genera

References

- Lee, Yuong-Nam; Ryan, Michael J.; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugo (2010). "The first ceratopsian dinosaur from South Korea" (PDF). Naturwissenschaften. 98 (1): 39–49. Bibcode:2011NW.....98...39L. doi:10.1007/s00114-010-0739-y. PMID 21085924.

- Rich, Thomas H.; Kear, Benjamin P.; Sinclair, Robert; Chinnery, Brenda; Carpenter, Kenneth; McHugh, Mary L.; Vickers-Rich, Patricia (2014). "Serendipaceratops arthurcclarkei Rich & Vickers-Rich, 2003 is an Australian Early Cretaceous ceratopsian". Alcheringa. 38: 456–479. doi:10.1080/03115518.2014.894809.

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.

- Dodson, P. 1996. The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 346pp.

- Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Rey, Luis V. (2007). Dinosaurs: the most complete, up-to-date encyclopedia for dinosaur lovers of all ages. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- You H. & Dodson, P. 2004. Basal Ceratopsia. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 478-493.

- Dodson, P., Forster, C.A., & Sampson, S.D. 2004. Ceratopsidae. In: Dodson, P., Weishampel, D.B., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 494-513.

- Dodson, Peter (1996). The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. pp. 49, 63. ISBN 978-0-691-02882-8.

- Makovicky, Peter J. (2012). "Marginocephalia". In M. K. Brett-Surman; Thomas R. Holtz; James O. Farlow (eds.). The Complete Dinosaur (2nd ed.). Indiana University Press. p. 540. ISBN 978-0-253-35701-4.

- Dodson, Peter; Forster, Catherine. A; Sampson, Scott D. (2004). "Ceratopsidae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 494–513. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Marsh, Othniel C. (1889). "The skull of the gigantic Ceratopsidae". American Journal of Science. 3rd Series. 38: 501–506.

- Hatcher, J.B., Marsh, O.C. and Lull, R.S. (1907). The Ceratopsia. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 300 pp. ISBN 0-405-12713-8

- Gillette, D.D. (1999). Vertebrate Paleontology In Utah. Utah Geological Survey, 554 pp. ISBN 1-55791-634-9, ISBN 978-1-55791-634-1

- Cope, E.D. (1876). "Descriptions of some vertebrate remains from the Fort Union Beds of Montana". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 28: 248–261.

- Marsh, O.C. (1890). "Additional characters of the Ceratopsidae, with notice of new Cretaceous dinosaurs". American Journal of Science. 39 (233): 418–429. Bibcode:1890AmJS...39..418M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-39.233.418.

- Steel, R. 1969. Ornithischia. In: Kuhn, O. (Ed.). Handbuch de Paleoherpetologie (Part 15). Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag. 87pp.

- Zhao; Gao; Fox; Du (2007). "Endocranial morphology of psittacosaurs (Dinosauria: Ceratopsia) based on CT scans of new fossils from the Lower Cretaceous, China". Palaeoworld. 16 (4): 285–293. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2007.07.002.

- Benton, M.J. (2004). Vertebrate Palaeontology, Third Edition. Blackwell Publishing, 472 pp.

- Rich, T.H. & Vickers-Rich, P. 2003. Protoceratopsian? ulnae from the Early Cretaceous of Australia. Records of the Queen Victoria Museum. No. 113.

- Godefroit, Pascal; Lambert, Olivier (2007). "A re-appraisal of Craspedodon lonzeensis Dollo, 1883 from the Upper Cretaceous of Belgium: the first record of a neoceratopsian dinosaur in Europe?". Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre. 77: 83–93.

- Lindgren, Johan; Currie, Philip J.; Siverson, M.; Rees, J.; Cederström, Peter; Lindgren, Filip (2007). "The first neoceratopsian dinosaur remains from Europe". Palaeontology. 50 (4): 929–937. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00690.x.

- Sereno, P.C. (1998). "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with applications to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 210: 41–83. doi:10.1127/njgpa/210/1998/41.

- You, H.; Dodson, P. (2003). "Redescription of neoceratopsian dinosaur Archaeoceratops and early evolution of Neoceratopsia". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 48 (2): 261–272.

- You H., Li D., Lamanna, M.C., & Dodson, P. 2005. On a new genus of basal neoceratopsian dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Gansu Province, China. Acta Geologica Sinica (English edition) 79(5): 593-597.

- Xu, X.; Makovicky, P.J.; Wang, X.; Norell, M.A.; You, H. (2002). "A ceratopsian dinosaur from China and the early evolution of Ceratopsia". Nature. 416 (6878): 314–317. Bibcode:2002Natur.416..314X. doi:10.1038/416314a. PMID 11907575.

- Makovicky, P.J. 2001. A Montanoceratops cerorhynchus (Dinosauria: Ceratopsia) braincase from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, In: Tanke, D.H. & Carpenter, K. (Eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Pp. 243-262.

- Xu, X.; Forster, C.A.; Clark, J.M.; Mo, J. (2006). "A basal ceratopsian with transitional features from the Late Jurassic of northwestern China". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1598): 2135–2140. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3566. PMC 1635516. PMID 16901832.

- Chinnery, B (2005). "Description of Prenoceratops pieganensis gen. et sp. nov. (Dinosauria: Neoceratopsia) from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (3): 572–590. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0572:doppge]2.0.co;2.

- Makovicky, P.J.; Norell, M.A. (2006). "Yamaceratops dorngobiensis, a new primitive ceratopsian (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Cretaceous of Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 3530: 1–42. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2006)3530[1:ydanpc]2.0.co;2. hdl:2246/5808.

- Farke, A. A.; Maxwell, W. D.; Cifelli, R. L.; Wedel, M. J. (2014). "A Ceratopsian Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Western North America, and the Biogeography of Neoceratopsia". PLoS ONE. 9 (12): e112055. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k2055F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112055. PMC 4262212. PMID 25494182.

- Morschhauser, E.M.; You, H.; Li, D.; Dodson, P. (2019). "Phylogenetic history of Auroraceratops rugosus (Ceratopsia: Ornithischia) from the Lower Cretaceous of Gansu Province, China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (Supplement): 117–147. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1509866.

- Chinnery, B.J.; Lipka, T.R.; Kirkland, J.I.; Parrish, J.M.; Brett-Surman, M.K. (1998). "Neoceratopsian teeth from the Lower to Middle Cretaceous of North America. In: Lucas, S.G., Kirkland, J.I., & Estep, J.W. (Eds.). Lower and Middle Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 14: 297–302.

- Sues, H.-D.; Averianov, A. (2009). "Turanoceratops tardabilis—the first ceratopsid dinosaur from Asia". Naturwissenschaften. 96: 645–652. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0518-9.

- Erickson, G.M.; Tumanova, T.A. (2000). "Growth curve of Psittacosaurus mongoliensis Osborn (Ceratopsia: Psittacosauridae) inferred from long bone histology". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 130 (4): 551–566. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2000.tb02201.x.

- Dodson, P (1976). "Quantitative aspects of relative growth and sexual dimorphism in Protoceratops". Journal of Paleontology. 50: 929–940.

- Lehman, T.M. 1990. The ceratopsian subfamily Chasmosaurinae: sexual dimorphism and systematics. In: Carpenter, K. & Currie, P.J. (Eds.). Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 211-230.

- Bakker, R.T. (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking The Mystery of the Dinosaurs and Their Extinction. William Morrow:New York, p. 438. ISBN 0-14-010055-5

- Naish, D. (1999). EVIL FANGED CERAPODANS Archives of the Dinosaur Mailing List, April 23, 2011.

- Witton, M. (2007). Ha Ha! Charade You Are Mark Witton's Flickr, April 23, 2011.

- Paul, G.S.; Christiansen, P. (September 2000). "Forelimb posture in neoceratopsian dinosaurs: implications for gait and locomotion". Paleobiology. 26 (3): 450–465. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0450:FPINDI>2.0.CO;2.

- Longrich, N. (2010). "The Function of Large Eyes in Protoceratops: A Nocturnal Ceratopsian?", In: Michael J. Ryan, Brenda J. Chinnery-Allgeier, and David A. Eberth (eds), New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium, Indiana University Press, 656 pp. ISBN 0-253-35358-0.

- Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology". Science. 332 (6030): 705–8. Bibcode:2011Sci...332..705S. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820.

- Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 331-336.

- McWhinney, L., Carpenter, K., and Rothschild, B., 2001, Dinosaurian humeral periostitis: a case of a juxtacortical lesion in the fossil record: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, pp. 364-377.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ceratopsia. |

- Introduction to the Ceratopsians, University of California Museum of Paleontology

- Marginocephalia at Palaeos.com (technical)