Stella power stations

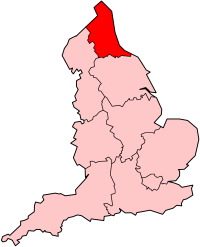

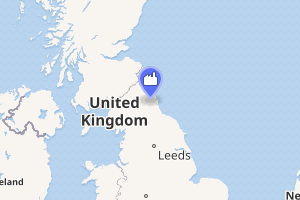

The Stella power stations were a pair of now-demolished coal-fired power stations in the North East of England that were a landmark in the Tyne valley for over 40 years. The stations stood on either side of a bend of the River Tyne: Stella South power station, the larger, near Blaydon in Gateshead, and Stella North power station near Lemington in Newcastle. Their name originated from the nearby Stella Hall, a manor house close to Stella South that by the time of their construction had been demolished and replaced by a housing estate.[1] They operated from shortly after the nationalisation of the British electrical supply industry until two years after the Electricity Act of 1989, when the industry passed into the private sector.

| Stella power stations | |

|---|---|

Stella North (left) and South (right) power stations Viewed from Newburn Bridge on 31 October 1987 | |

| |

| Official name | Stella North and South power stations |

| Country | England |

| Location | Newburn |

| Coordinates | 54°58′22″N 1°43′38″W |

| Status | Demolished and sites redeveloped |

| Construction began | 1951 |

| Commission date | 1954-57 |

| Decommission date | 1991 |

| Construction cost | £40.5 million |

| Owner(s) | Central Electricity Authority (1954–1957) Central Electricity Generating Board (1957–1990) National Power (1990–1991) |

| Thermal power station | |

| Primary fuel | Bituminous coal |

| Power generation | |

| Units operational | North station: Four 60 MW Parsons South station: Five 60 MW Parsons |

| Nameplate capacity | 1957: 240 MW North station 300 MW South station 1991: 224 MW North station 300 MW South station |

| External links | |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

These sister stations were of similar design and were built, opened, and closed together. Stella South, with a generating capacity of 300 megawatts (MW), was built on the site of the Blaydon Races,[2] and Stella North, with a capacity of 240 MW, on that of the former Lemington Hall.[3] They powered local homes and the many heavy industries of Tyne and Wear, Northumberland and County Durham. The large buildings, chimneys and cooling towers were visible from afar. Their operation required coal trains on both sides of the river to supply them with fuel and river traffic by flat iron barges to dump ash in the North Sea. After their closure in 1991, they were demolished in stages between 1992 and 1997.[4] Following the stations' demolition, the sites underwent redevelopment: the North site into a large business and industrial park, the South into a housing estate.

History

Development

The British demand for electricity increased after the Second World War. In the North East of England this led to the expansion of existing power stations at Dunston and Billingham in the late 1940s, the two new Stella power stations, and the construction of two more large stations built at Blyth later in the 1960s. This new generating capacity quickly met the demand for power.[5] The British Electricity Authority were granted permission to construct the Stella North and Stella South power stations in 1951. The two stations were originally projected to cost around £15,000,000.[6]

The site chosen for Stella North was the Newburn Haugh, which was the site of Lemington Hall.[7][nb 1] Lemington Hall was demolished in 1953 during the construction of Stella North.[9] Stella South was built on the Stella Haugh, the site of the Battle of Newburn in 1640. A cannonball from the battle was on display in the South station for many years, after having been dredged from the river bed.[10] Between 1887 and 1916, the Stella Haugh had been the site of the annual Blaydon Races,[2] which stopped after a riot broke out following allegations of race fixing.[11] Just before the construction of the South station the haugh had two uses. Blaydon Rugby Club's ground had been there since 1893, but in 1950 it was compulsorily purchased by the British Electricity Authority for £1,000. The club moved to a new ground in Swalwell, which it still uses.[12] Newcastle University Boat Club had owned a boathouse on the site since 1929, but in 1951 the British Electricity Authority requisitioned it, forcing the club to move upstream to its current location in Newburn.[13]

The addition of various power lines was needed to connect the power stations to the National Grid. These included a 275 kilovolt (kV) connection from Stella to West Melton, and another 275 kV connection from Stella to Carlisle. The towers for these connections were to stand at 115 feet (35 m), rather than the 85 feet (26 m) towers of the existing grid system.[14] The line from Stella to Carlisle, which was to consist of 250 towers spaced at 320 meters over a distance of around 60 miles (97 km), came up against opposition when first proposed. The Northumberland County Planning Authority launched a public enquiry in 1951, and Hexham Rural District Council held a meeting. The Ministry of Agriculture and other outdoor associations voiced their concerns, as it was feared that the line would interfere with good farming land. An alternative route was proposed, but in view of its additional cost of £72,000 it was turned down, and the Ministry of Fuel and Power gave the line the go-ahead.[15][16]

Construction

Both of the stations were designed by Newcastle upon Tyne-based architects L J Couves & Partners, and construction work began in 1951.[2] The Cleveland Bridge Company were contracted to construct the steel frames for the stations' main buildings, including their turbine halls, boiler houses, workshops and stores buildings.[17][18] Various other companies were contracted for the construction of other parts of the station. Sir Robert McAlpine & Sons were contracted for site clearance, provision of the foundations for the main and ancillary buildings, as well as the diversion of streams and sewers.[15][19] Davenport Engineering Co. were responsible for the construction of the North station's cooling towers, as well as the stations' ancillary buildings. P.C. Richardson & Co. built the stations' brick chimneys.[20] Aiton & Co. installed the stations' low-pressure piping equipment.[19] Underwater electrical work was carried out by British Royal Navy frogman Lionel "Buster" Crabb, chosen for the dangerous job because he wore a rubber diving suit at a time when most divers used canvas.[21]

The first generating sets of the stations became operational on 20 December 1954.[2] However, it was not until 1956 that all four of the North station's units were commissioned, and 1957 before all five of the South station's units generated electricity.[22] The cost of the two stations in total came to around £40,500,000.[23]

On the morning of 14 December 1955, during the stations' construction, switchgear exploded in the South station's substation, closing down the generators. Dunston power station could not take the extra load and it also shut down, creating a total blackout on Tyneside. Around 400,000 people were affected by the fault, including 20,000 miners trapped in over a hundred collieries. Power was fully reconnected by that evening. but the failure caused an interruption of work and services worth more than £1,000,000, as well as the loss of 300 megawatts of electricity.[24][25][26]

Post-commissioning

Although developed by the British Electricity Authority, the stations were first operated by the Central Electricity Authority, following the Electricity Reorganisation (Scotland) Act 1954. From 1957 they were operated by the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB), following the Electricity Act 1957.[2][27]

In 1961, Stella North was presented with the Hinton Cup, the CEGB's "good house keeping trophy". The award was presented by Sir Christopher Hinton, the first chairman of the CEGB. The station's achievement was attributed to the fact the station's annual efficiency had never been less than 29.1%. The station also won the North East regional award for the second year in a row in 1961.[28] In March 1967, Stella South's male first aid team won a national first aid competition in Harrogate, organised by the CEGB. Over 150 teams took part.[29]

In 1966, Stella North was at the centre of a legal case in which three men were found guilty of conspiracy to defraud after trying to sell the CEGB poor quality coal when contracted to deliver high quality coal. The three men involved were D.C.P. Brooksbank, a salesman for a coal firm; J.W. Patterson, a sampler at the power station, and M. Ridley, a contractor. Their scheme was for Patterson to substitute samples of reasonably good coal for the samples of poor coal taken from the lorries. However they were found out only two days after starting the scheme, when a foreman at the station saw Patterson dropping a bag of cement into the sampling bin, and reported the incident. Ridley was found to have planned the fraud, and was jailed for a year, while Brooksbank was fined £150 and Patterson £75.[30]

Design and specification

The main visible features of the stations were their large boiler houses, turbine halls, cooling towers and pairs of chimneys; other facilities on both sites included offices, coal sorting areas, small fire stations and workshops. The power stations had the "brick-cathedral" style of design[2] popular for power stations in the 1930s and 1940s and, as of 2009, still tenuously surviving at Battersea power station in London.[31]

The main buildings of the South station had a total length of 130 m (430 ft) and a width of 81 m (266 ft); their tallest point, the roof of the boiler house, was 44 m (144 ft) high.[32] The main buildings of the North station were of a similar length and height, but in total slightly narrower as the station had one less generator unit. This also meant it had a smaller generating capacity; it was sometimes erroneously termed the South station's "B" station.[33]

The boiler houses and turbine halls were all-welded steel structures, consisting of box-type main columns and roof girders, clad with brick and glazed in parts.[32] Each of their four chimneys was made of brick and stood 120 m (390 ft) tall, weighing about 5,000 tonnes.[34] The North station's four 73 m (240 ft) cooling towers were made from reinforced concrete and were of the typically hyperbolic, natural-draft design.[2]

The South station had five generating sets and the North station had four.[22][35][36] Each generating set had a bunker for 1,250 tonnes of coal, fed by a conveyor from the coal store.[32] This conveyor belt system was built by E. N. Mackley & Co, Gateshead.[37] Each bunker fed coal into a pulveriser, manufactured by Raymond.[38] From here it was fed into a boiler in powder form and burned. All of the boilers were suspended from the boiler houses' steel frames, and were made by Clarke Chapman Group Ltd, Gateshead.[32][35] The boilers were forged in Sheffield, the first of the nine arriving at Stella South in 1953. At 62 tonnes, the boilers were at the time the largest ever made in the UK.[39] The boilers were of the radiant-heat type, comprising a water-cooled combustion chamber, controlled-type superheater and an economiser. Each of the boilers had an evaporation rating of 550 kL/h, a steam pressure of 950 psi and a steam temperature of 925 °F.[38][40] Each boiler was equipped with two forced and two induced Howden fans, twenty-two electrically operated Clyde soot blowers, an automatic control system made by Bailey and Sturtevant electrostatic precipitators.[40][41] Each station was designed to burn 2,000 tonnes of bituminous coal a day.[3][42]

Each boiler powered a turbo generator, made by Parsons, Newcastle upon Tyne.[3] These were three-cylinder reaction type steam turbines operating at 3,000 rpm, generating 60 MW of electricity.[40] The stations used them because of a Statutory Order of the Ministry of Supply in November 1947 that all turbo alternators made for the home market could only be of 60 MW at advanced steam conditions.[43][44] Stella South had a total generating capacity of 300 MW and Stella North originally 240 MW (later recorded as only 224 MW).[3][45] The stations were the first to use silica removal beds in their turbines, a development which became standard within the CEGB's power stations for some time.[46] In 1967, one of the sets at Stella South became the world's first in commercial operation to use brushless excitation. The set was modified by Parsons to use A.C. exciters and silicon diode rectifiers.[47] The stations' switchgear was manufactured by A. Reyrolle & Company.[24]

The power stations were illuminated by what was then the most powerful lighting installation in North East England. The North station was lit up by 60 flood lights, 15 on each of four towers; the South station also had four towers, but each held 26 flood lights. The Central Electricity Authority justified the use of 194 flood lights over the two sites as "economical, safe and much more efficient than lighting the stations at street level".[48]

Operations

Coal transportation

The stations were in the heart of the North East coal field, which at the time of their opening had hundreds of collieries.[49] Coal was delivered straight to the stations by rail. The Newcastle and Carlisle Railway was used for the South station, where 22 railway sidings were built.[2] Trains could only enter the sidings when travelling in a westerly direction.[50]

The Scotswood, Newburn and Wylam Railway (SN&WR) supplied the North station, trains reaching the power station via a junction at Newburn.[50] Despite the SN&WR's closure on 11 March 1968, and the rerouting of the Newcastle & Carlisle Railway through Dunston in 1982, the track between Scotswood and Newburn was retained for supplying the North station, as well as for rail access to the neighbouring Ever Ready battery factory and Anglo Great Lakes Graphite Plant.[50][51][52][53] The tracks outlived the power stations, and were finally lifted when the Ever Ready factory shut down in 1992.[54] Part of the line serving the station is now a well-used section of the Hadrian's Way National Trail.[55]

A small home fleet of locomotives was used to shunt the coal wagons once they had arrived at the stations. Originally this included Robert Stephenson and Hawthorns 0-4-0ST No.20 and No.21, and Sentinel No.25.[56][57] Engine No.25 was used exclusively at the North station, but was converted to diesel-hydraulic by Thomas Hill of Kilnhurst in 1967, becoming Thomas Hill 188. It returned to the station but was taken out of use in 1983 and scrapped by C F Booth of Rotherham.[57] After the closure of the stations, engine No.21 was sent to be preserved at the Tanfield Railway site, near Sunniside in Gateshead.[56] During the 1970s the steam locomotives were replaced by diesel locomotives. These included a Fowler 0-6-0 and CEGB No. 24 Vanguard 0-4-0 [58][59] CEGB No. 24 has since been sent to Statfold Barn Railway for preservation.[60]

The stations were picketed during the UK miners' strike of 1972, stopping coal deliveries to them.[61]

Cooling system

Water is essential to a thermal power station to produce the steam needed to turn the steam turbines and generate electricity. Water cycled through the Stella stations' systems was taken from the River Tyne; after use it was cooled before being discharged back into the river. The North station's water cooling system consisted of four large 60-cubic-metre (2,100 cu ft) natural draft cooling tower units,[62] 73 m (240 ft) tall and made of reinforced concrete.[2] The South station used a syphon cooling system instead of cooling towers, consisting of five 300-cubic-metre (11,000 cu ft) units, made up of five underground pipes, each 2.1 metres (6 ft 11 in) in diameter, with valves and screens.[62]

Ash removal

Fly ash and bottom ash are two by-products from the burning of coal in power stations. Ash from the Stella stations was taken out to sea by three flat iron barges: Bobby Shaftoe, Bessie Surtees and Hexhamshire Lass.[63] All three were built by Charles Hill & Sons of Bristol, in 1955.[64] Bessie Surtees was the first to be put into service, in April 1955.[63] On each trip, each ship took up to 500 tonnes of ash from the stations down the river and dumped it in the North Sea, 4.8 km (3.0 mi) off the coast. Originally, they carried ash waste from Dunston power station as well.[64] Their frequent passages made them a common sight on the Tyne. Each was 46 m (151 ft) long and 10 m (33 ft) wide, weighed 680 tonnes, and had a crew of seven. They were managed by Stephenson Clarke Shipping Ltd but owned by the CEGB.[64] The ships went further up the Tyne than did any other, and so needed a shallow draft.[64] The entire load of ash was dumped through two hydraulically operated doors in only a few minutes.[63]

As early as the 1960s, the power stations' operating hours were decreased due to the opening of the much larger Blyth power station in Northumberland. This meant that less ash was produced by the Stella and Dunston stations; so by the end of the 1960s, the CEGB sold Hexhamshire Lass and Bobby Shaftoe. The former went to a firm in Fareham, Hampshire, where it worked as a sand dredger until scrapped in 1993; the latter to a French dredging company.[64]

After the closure of Dunston Staithes in 1980, the Swing Bridge downstream of the stations seldom had to be opened. (Because Bessie Surtees was low lying, it was able to pass underneath the bridge at low tide.)[65] However, on 15 December 1975, Bessie Surtees collided with the Swing Bridge, forcing it to close for the rest of that weekend.[64]

Environmental impact

When built, the power stations were fitted with electrostatic precipitators, to reduce the amount of smoke and dust emitted from the stations' chimneys. At the time, this was the most up-to-date method to prevent pollution from power stations.[41]

Despite these precautions, pollution from the power stations was still a factor. In 1954, consideration was given to scrapping the plan to build the Union Hall housing estate in Lemington because of probable pollution from nearby power stations. This was mainly because some of the houses were as high as, if not higher than, the power stations' chimneys. At times, this meant the estate being exposed to as much as 1.25 parts per million of sulphur dioxide. However the estate was still built, as these peak conditions were thought unlikely to occur on more than 18 days in a year.[66]

Smoke was not the only thing emitted from the power station. In July 1956, the discharge of cooling water from the stations was noted to have increased the water temperature of the river by 1.5 °C between Ryton and Scotswood. However, this was found to not be too deleterious, as it did not seem to affect the passage of migratory fish.[67] In fact, because of the stations' introduction of warm water into the river, basking sharks were known to be attracted to the area.[68]

From the start, the power stations' fly ash was dumped in the North Sea, and 800,000 tonnes of fly ash were dumped between the Stella and Blyth stations in 1976.[69] By 1991, National Power's licence had been restricted to dumping only 50,000 tonnes of ash a year from the Stella power stations. By this point the North East coast was the only place in Europe to dump fly ash at sea. Fly ash dumping had been found to make sea bed inert, with much life being smothered and killed by the fly ash. It was also found to create problems for the fishing industry, when their trawlers caught large lumps of it. The licence for Stella was terminated in May 1991, with the stations' closure. Blyth power stations' licence was terminated by the end of 1992, ending fly ash dumping in the North Sea.[70][71]

Closure and demolition

Closure

By the mid-1980s closure of the stations was being considered, and in 1984, was considered for a combined heat and power scheme.[72] After the privatisation of the Central Electricity Generating Board in 1989, the stations passed into the ownership of National Power.[73] After almost 37 years of use they were decommissioned in May 1991 as outdated and uneconomical to operate.[71][74] They had been overtaken technologically, and had lower generating capacity than newer plants such as Drax. Their closure coincided with that of a large number of coal mines in the North East of England, just after the privatisation of both the electricity industry and the National Coal Board in the early 1990s.[49][75][76]

Following the closure of the power stations at Stella, as well as those at Dunston and Blyth (in 1981 and 2001 respectively), the northern part of North East England has become heavily dependent upon the National Grid for electricity. However, in the South of the region there are still two large power stations, at Hartlepool and Wilton.[45]

The stations' closure also forced the Tyne Sea Scouts, who had operated from the North station since 1978, to seek new accommodation. The scouts had moved into the station when their boat house in Blyth was deemed unsafe and demolished. They had been provided with two site offices, storage in the power station complex, and permission to keep their boats at the North station's jetty, at the end of which they had a slipway built.[77]

Demolition

The large buildings and structures of the stations were demolished in stages throughout the 1990s. The four cooling towers were demolished by explosives on 29 March 1992, in front of thousands of spectators.[78] St Paul's Developments then bought the two sites from National Power in 1993.[73][79] Both stations were demolished by Thos W Ward Industrial Dismantling of Barnsley,[35] which started with the South station, whose twin chimneys were destroyed on 29 October 1995 by 82 kilograms (181 lb) of explosives.[80] Its turbine hall followed, before the boiler house went on 1 February 1996.[81] Stella North then stood alone for almost a year before its turbine hall was demolished on 27 January 1997 and its bunker bay building was demolished on 22 June.[35][82][83] The boiler house followed straight after, but its complete destruction took three attempts. Most of it went on 22 June; the rest followed over the next two days.[84] Its two chimneys, the last obvious reminder of the Stella power stations, were pulled down a month later on 27 July.[85]

The power stations were among the last remaining heavy industrial buildings in modern Tyneside, and their demolition was felt by many Tynesiders to have marked the end of industrial Tyneside. The National Trust was then uninterested in the preservation of modern structures such as this.[4]

Redevelopment

North site

CCGT power station proposal

In 1997[86] there had been plans for a £130 million combined cycle gas turbine power station on the site of the Ever Ready battery factory to the West of the site of the North station.[87] AES Electrical applied to the Department of Trade and Industry for permission to build the station, which would have been twice as efficient as the coal-fired Stella stations and the first major electricity generation site built in Tyne and Wear in over 40 years.[88] The station would have had a generating capacity of 350 MW.[86] It would have taken three years to build, and created 400 construction jobs, as well as 40 full-time jobs after construction. But the proposal was opposed by the coal mining industry and dropped.[35]

Newburn Riverside

Shortly after the North station was demolished, its site was reclaimed along with the site of the neighbouring Anglo Great Lakes Graphite Plant. The plant had made high-purity graphite for use in magnox nuclear reactors, and operated using the North station's available excess generating capacity, as large quantities of cheap electricity were essential for production.[89] It was demolished around the same time as the stations, and left the site littered with graphite blocks.[90] At 93 ha (230 acres), the reclamation of the two neighbouring sites was one of the UK's largest land reclamation schemes; it was completed in 2000.[33][91] This made way for an industrial/business park, Newburn Riverside, the first phase of whose construction was completed in 2005. As of 2009 it was still expanding, and expected to provide 5,000 jobs and £116 million of private sector investment once completed.[92] The park has a 4 km (2.5 mi) cycle route and nature trail around its edge, which takes visitors, walkers and cyclists beside the river and past the point in which the North station's cooling towers once stood.[93] One of the buildings in the business park was named Stella House, as a tribute to the power station. It is occupied by One NorthEast, the regional development agency for the North East of England.[94][95] In early 2012, Stella House became the National HQ of the NHS Business Service Authority following the winding down of One NorthEast. Little else commemorates the power stations, but they are briefly mentioned in a plaque on Stella Road near the South station's site marking the Blaydon Races: "Official racing started in 1861 on Blaydon Island which lay North of here. The song was written in 1862. From 1887 to 1914 the race course was on Stella haugh, the site of the former power station."[96]

As well as the NHSBSA, the other key occupiers of the Newburn Riverside site are DEFRA, North East Ambulance Trust, MacFarlane Packaging, True Potential LLP, Northumberland and Tyne & Wear Strategic Health Authority and Stannah Stairlifts.[97]

South site

Following the completion of the South station's demolition in 1996, thousands of pounds were spent on a number of security measures; the site was fenced off, bunding was installed, warning signs were put up and security patrols took place. However, large sections of the fencing were stolen and the warning signs were ignored. Ultimately this led to one man being trapped on the site for five hours on 22 May 1997. He had been looking for scrap metal and power cables, and had climbed through a small hole into an underground room, from which he had to be rescued by fire crews. The site was then designated a danger zone.[98] The derelict site was vandalised in July 1999, when people hurled burning tyres into the sub-station, creating a fire and damaging cables worth £150,000.[99]

Riverside Crescent

As of 2007, the 14 ha (35 acres) site of the South station is under redevelopment, after having sat as a brownfield site for almost 10 years. St Paul's Developments, the site developer, had often applied for planning permission to build housing and leisure facilities on the site over the course of six years, only to be refused. It was finally granted permission to begin building a £4.7 million housing estate on the site in 2007. Named Riverside Crescent, this is being constructed by Barratt and Persimmon. It will have 522 residential units, from two-bedroom flats to five-bedroom houses, as well as 1.6 ha (4.0 acres) of open space, a riverside walkway and a restaurant. A new bus link to Blaydon will improve transport links.[100] The plans for the residential development first went on display at Stella RC Primary School on 5 October 2005. Other proposals for the site had included industrial development, which met opposition, and restoration to grassland, seen as unfeasible.[101]

Despite the demolition in 1996 of all of the above-ground structure of the South station, foundations, culverts and more remained. These needed to be removed before construction could start.[102] The removal of these underground structures was completed in early 2007, whereupon construction of the houses began immediately.

Remnants

Due to the significant reclamation on the two sites very little evidence remains of the power stations, other than a small number of bricks and steel rods. Some minor structures have survived to the North West of the North station's site, including a road bridge over the rail line which served the station, a brick wall, and a concrete staircase. More obvious remains of the power stations are their three large sub-stations that still supply the local region.[103] Much of that electrical power was generated in Scotland's Cockenzie power station, transported via a 275 kilovolt (kV) and a 400 kV connection.[104]

Cultural use

The power stations were a strong local landmark.[21] Their chimneys could be seen along a roughly 13.8 km (8.6 mi) long section of the Tyne valley; from Bensham near Gateshead down to Heddon-on-the-Wall in Northumberland: almost no other building was present to obstruct the view.[105]

When still in operation, the power stations appeared in films and television programs shot in the Newcastle area. They appeared in Payroll, a movie made in 1961, starring Michael Craig. One of two security van operators lives in Stella park, a housing estate above the power station. It is prominently in the background whenever the van operator's home is shown.[106] In 1985, the Stella power stations are seen briefly in a shot in Seacoal, a movie made by Amber Films. They appear during a scene where the two protagonists, Ray and Betty, are travelling from Sunderland to Newcastle. (Lynemouth power station, a North East power station still in operation, is more prominent in the film.)[107] In Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads?, a British sitcom broadcast between 1973 and 1974, the stations themselves did not appear in the series, but in the end credits their ash boat, Bessie Surtees, could be seen passing Spiller's Wharf near Byker.[108] In 1981, it was featured in Swing Bridge Videos' Check it Out, a short film about youth unemployment in the west end of Newcastle.[109] In the mid-1990s, the decommissioned stations were photographed by north eastern artist John Kippin as part of his work The Secret Intelligence of the Silent. This piece was exhibited at the Laing Art Gallery in 2012 as part of the exhibition Futureland Now.[110]

See also

- Electricity Act 1947

- Electricity Act 1957

- Energy use and conservation in the United Kingdom

- List of power stations in England

- Northern Electric

- Timeline of the UK electricity supply industry

References

Notes

- "Demolition of Stella Hall, 1955". Gateshead Council. Archived from the original on 19 March 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- "Structure details". Newcastle University. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- "Coal-fired power plants in England - North". http://www.industcards.com/. 31 May 2008. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2008. External link in

|work=(help) - David Morgan Evans, David Thackray and Peter Salway, ed. (1996). The remains of distant times. 19. National Trust. p. 15. ISBN 0-85115-671-1. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- Simmons, Bob. "About Blyth Power Station". About Blyth. Archived from the original on 1 March 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- "Machinery". Machinery. The Machinery Publishing Co. 78: 1015. 1951. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- Old OS maps (Map) (1925 ed.). Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- Pearsall, Judy (ed.). Concise Oxford Dictionary (10th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1951). The Buildings of England: Northumberland. 15. Penguin Books. p. 295. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- Taylor, Rab (1996). "The battle of Stella Haugh". ScotWars: Scottish Military History and Re-enactment. Archived from the original on 7 July 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- Simpson, David. "Gateshead and South Tyneside". England's Northeast. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- Blaydon RFC. "The history of Blaydon Rugby Club". Blaydon RFC. Archived from the original on 8 February 2006. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- Newcastle University Boat Club. "History". Newcastle University Boat Club. Archived from the original on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- "Electrical Times". Electrical Times. 118: 802. 1950. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- "The Electrical Journal". The Electrical Journal. 147: 125, 270. 1951. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- "The Electrical Review". The Electrical Review. 150: 1313. 1952. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- Ellison, Mike. "A – Z list of bridges built by Cleveland Bridge Company". Archived from the original (DOC) on 27 May 2003. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- Foundrymen, Institute of British; Association, Welsh Engineers' Founders'; Association, Foundry Trades' Equipment Supplies (1952). "The Foundry Trade Journal". The Foundry Trade Journal. 93: 342. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- "Home acres". The Electrical Review. 19: 299. 1952. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- "The Electrical Review". The Electrical Review. 152: 1082. 1953. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- "Great British hero was a tower of strength". The Journal. 9 August 1997. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- "Generation disconnections since 1991". 2003. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- "The Electrical Times". The Electrical Times. 141: 798. 1962. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

the Stella stations on the Tyne had cost £75/kW. [Stations' total generating capacity was 540,000kW. 75 multiplied by 540,000 gives 40,500,000.]

- Marshall, Ray (7 November 2007). "A factory of memories". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- "Supply Breakdown, Newcastle". Hansard. 19 December 1955. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- Roberson, Lee (2000). The Gold Mine. Sword of the Lord Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 0-87398-339-4. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- "The electricity supply industry and the Central Electricity Generating Board" (PDF). Competition Commission. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- "The Electrical Journal". The Electrical Journal. D. B. Adams. 167: 27, 433. 1961. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- "Papers by command". Papers by Command. HMSO. 27: 52. 1966. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- "Electrical Times". Electrical Times. 149: 145. 1966. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- Heritage Protection Department (March 2007). "Utilities and communications buildings selection guide" (PDF). English Heritage. p. 10. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- Galbraith, Lt.-Colonel R. F. (January 1954). "Presidential address". The Structural Engineer. IStructE. 32 (1): 10. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- Michael, Gordon (19 January 2000). "One North East selects Taywood". Reed Business Information. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

The £100 million-plus project is at Newburn Riverside Industry Park in Newcastle, which formerly housed the Stella B power station and a graphite plant.

- North East Tonight (Television production). Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Tyne Tees Television. June 1997.

This afternoon the demolition experts turned their attention to the boiler house, some 50m high.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - "Power station set for blast". The Journal. 12 June 1997. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- "Twin chimneys to be flattened". The Journal. 25 July 1997. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- "Catalogue details". 31 March 1956. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- "The Engineers' Digest". The Engineers' Digest. 17: 70. 1956. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Machinery". Machinery. Machinery Publishing Company, Ltd. 83: 453. 1953. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- The Fuel Research Board (1956). "Fuel Abstracts": 84. Retrieved 11 February 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Mr. Popplewell; Mr. Geoffrey Lloyd (2 February 1953). "Generating Plant, County Durham (Pollution Prevention)". Hansard. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- Yellowley, T. "Aerial view of Stella Power Station". Archived from the original (PHP) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- Hannah, Leslie (1979). Electricity before nationalisation: A study of the development of the electricity supply industry in Britain to 1948. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-22086-2.

- Hannah, Leslie (1982). Engineers, managers, and politicians: The first fifteen years of nationalised electricity supply in Britain. London: Macmillan; Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2862-7.

- Bone, Anthony; Morag Hunter; Bill Wilkinson (1999). "Energy for a new century" (PDF). North East England: Government Offices for the English Regions. pp. 50, 106. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- Institution of Mechanical Engineers (1984). "Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers". Power and Process Engineering. Mechanical Engineering Publications for the Institution of Mechanical Engineers. 198: 262. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- "Electrical Times". Electrical Times. 152: 722. 1967. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- Wilson, Ian (17 November 2005). "Landmarks are in the spotlights". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- Simpson, David. "Coal mining and railways". pp. Rise and fall of coal mining 1800–1990. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- Baker, S.K. (1980) [1977]. Rail atlas Great Britain and Ireland (3rd ed.). OPC. p. 69. ISBN 0-86093-106-4.

- "North Wylam" (PHP). Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- Brooks, Philip R.B. (2003). "Where railways were born" (PDF). Wylam Parish Council. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- "Railways". Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- Pickford-Jones, Tim (25 August 2001). "Glass and a Gut". Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- "Outer west area committee" (DOC). Newcastle City Council. 12 July 2005. p. 6. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- Geoff Smith - Narrator (1963). Industrial steam across Britain (DVD). Stella South Power Station: Alcazar Video.

- "Lot 148". 1999. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- "Fowler 0-6-0 JF4240020 is seen at CEGB Stella South power station on 29 March 1981". Murray Liston. Fotopic.net. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- "One of the Vanguard locos at CEGB Stella South Power Station, CEGB No.24, August 1982". Murray Liston. Fotopic.net. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- Dixon, Sam (March 2008). "Standard-gauge CEGB No.24 on the traverser". Fotopic.net. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- "A personal view". March 1972. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- Robson, Tom (July 2005). "Backchat". Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- "Those magnificent men in their hopper barges". Evening Chronicle. 3 March 2003. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- Wilson, Ian (3 March 2003). "Hardworking Bessie". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- "Swing Bridge". Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- "The Electrical Journal". The Electrical Journal. 153: 509. 1954. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- Great Britain. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food; Great Britain. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries (1957). "Fishery Investigations". Fishery Investigations: 45. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "Some interesting facts about the Newburn Riverside reclamation" (PDF). August 2003. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- Directorate of Fisheries Research, Great Britain (1978). "Fishery research technical report": 2. Retrieved 15 February 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Increased Protection of the North Sea". 2 May 1990. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- Franklin, A. (1993). Monitoring and surveillance of non-radioactive contaminants in the aquatic environment and activities regulating the disposal of wastes at sea, 1991. p. 65. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "The reports and accounts of the electricity and gas industries for 1983-84". Papers by Command. House of Commons. 15: 15. 1984. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Stella site homes backed". Evening Chronicle. 21 December 2000. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- "Going down with a bang". Evening Chronicle. 27 January 1997. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "National Coal Board". Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- Newbery, David; Pollitt, Michael (September 1997). "The restructuring and privatisation of the CEGB - was it worth it?". Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- "Story of the Tyne Sea Scouts". Evening Chronicle. 13 April 2004. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- "Coal and power" (PDF). pp. 912q. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- "5,000 jobs hope in techno-park". The Journal. 15 June 1995. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "Stella North may be blasted". Evening Chronicle. 3 November 1995. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "Homes plan for power site". Evening Chronicle. 1 February 1996. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "Sandra brings the house down". The Journal. 27 January 1997. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "Pensioner hurt in fire". Evening Chronicle. 16 June 1997. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- "On the count of three". Evening Chronicle. 24 June 1997. Retrieved 29 October 2008.

- "End of the road for chimneys". Evening Chronicle. 24 July 1997. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- Mr. Battle (31 July 1997). "Power Stations". Hansard. Retrieved 2 September 2009.

- "Powering ahead for jobs". Evening Chronicle. 12 March 1997. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- "Power plant could spark 6,500 jobs". The Journal. 12 March 1997. Retrieved 28 October 2008.

- National Trade Press Ltd, ed. (1957). Nuclear engineering. 2. Temple Press. p. 2. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- Bell, Christopher (1 May 2003). "Salvaged block". Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- "Work starts on One North East's Newburn HQ". One NorthEast. 25 February 2002. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- "New road to bring new business to Newburn". One NorthEast. 22 July 2005. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- "Environmentally friendly home for One NorthEast". 17 March 2003. Retrieved 14 August 2008.

- Barnett, Elaine (27 December 2002). "Agency on move keeps local office". Evening Gazette. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- "Head Office Archived 14 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine". One North East. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Pears, Brian (26 October 2008). "Commemorative plaques in Gateshead Borough". Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- "Gateway West". Archived from the original (PHP) on 3 March 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- Sadler, Polly (23 May 1997). "Owners warn of potential danger at former power station". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- "Vandals hit cables". Gateshead Post. 14 July 1999. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- "Barratt to deliver 1,000 homes as work begins on two major North East sites". 5 October 2007. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- Wallace, Jonathan (5 October 2007). "Stella South Power Station site future". Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- Laing, Iain (26 October 2007). "500 new riverside homes on the site of old power station". The Journal. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- "Grid capacity study". PB Power. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- "Cockenzie Power Station" (PDF). p. 3. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- Newcastle upon Tyne, Sunderland, Durham (Map) (1992 ed.). 1 : 15840. A to Z. Geographer's A–Z Street Atlas. pp. 36–37, 54–60. ISBN 0-85039-155-5.

- Sidney Hayers - Director, Norman Priggen - Producer (1961). Payroll (DVD). Event occurs at 27:57–28:39, 44:46–45:00. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- Ray Stubbs and Amber Styles - Actors (1985). Seacoal (VHS). Newcastle upon Tyne: Amber Films. Event occurs at 03:55–04:04. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- Bernard Thompson, James Gilbert - Producers (1973). Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads? (DVD). BBC. Event occurs at 25:00–30:00.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Check it out on YouTube

- Kippin, John (2012). Secret Intelligence. Newcastle upon Tyne: University of Plymouth Press. p. 106. ISBN 9781841023236. Archived from the original on 7 December 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

Bibliography

- Baker, S.K. (1980) [1977]. Rail Atlas of Britain (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford Publishing Company. ISBN 0-86093-106-4.

- Baker, S.K. (2007) [1977]. Rail Atlas - Great Britain & Ireland (11th ed.). Oxford Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-86093-602-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stella Power Station. |

- Barratt Homes – website for current redevelopment of South site.

- Flickr – an album of photos from during the stations' demolition.

- Fotopic – a picture of a fire engine which worked at the power stations.

- Napper Architects – designs for Riverside Crescent.

- RootsWeb – an account of a worker being injured during the construction of the power stations.

- SINE Project – a collection of images showing the power stations.

- YouTube – a short animation of the failed attempt to demolish the boiler house.

- YouTube – a collection of newsreels showing the demolition of the Stella South chimneys and the Stella North boiler house.

- YouTube – a documentation of the Blaydon Races centenary celebrations in 1962, which includes footage of a boat race past the power stations.

- YouTube – a film showing a train journey between Gateshead and Hexham on the Newcastle to Carlisle railway, which includes passing the power stations.

- YouTube - footage from a train passing the power station in 1983

- YouTube - Check it Out by Swing Bridge Video, which features the stations