Swazi language

The Swazi, Swati or siSwati language (Swazi: siSwati) is a Bantu language of the Nguni group spoken in Eswatini and South Africa by the Swazi people. The number of speakers is estimated to be in the region of 2.4 million. The language is taught in Eswatini and some South African schools in Mpumalanga, particularly former KaNgwane areas. Swazi is an official language of Eswatini (along with English), and is also one of the eleven official languages of South Africa.

| Swazi | |

|---|---|

| siSwati | |

| Pronunciation | [sísʷaːtʼi] |

| Native to | Eswatini, South Africa, Lesotho, Mozambique |

Native speakers | 2.3 million (2006–2011)[1] 2.4 million L2 speakers in South Africa (2002)[2] |

| Latin (Swazi alphabet) Swazi Braille | |

| Signed Swazi | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ss |

| ISO 639-2 | ssw |

| ISO 639-3 | ssw |

| Glottolog | swat1243[3] |

S.43[4] | |

| Linguasphere | 99-AUT-fe |

| The Swazi Language | |

|---|---|

| Person | liSwati |

| People | emaSwati |

| Language | siSwati |

| Country | eSwatini |

|

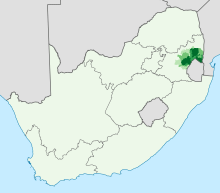

0–20%

20–40%

40–60% |

60–80%

80–100% |

|

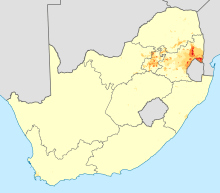

<1 /km²

1–3 /km²

3–10 /km²

10–30 /km²

30–100 /km² |

100–300 /km²

300–1000 /km²

1000–3000 /km²

>3000 /km² |

Although the preferred term is "siSwati" among native speakers, in English it is generally referred to as Swazi. Swazi is most closely related to the other Tekela languages, like Phuthi and Northern Transvaal (Sumayela) Ndebele, but is also very close to the Zunda languages: Zulu, Southern Ndebele, Northern Ndebele, and Xhosa.

Dialects

Swazi spoken in Eswatini can be divided into four dialects corresponding to the four administrative regions of the country: Hhohho, Lubombo, Manzini, and Shiselweni.

Swazi has at least two varieties: the standard, prestige variety spoken mainly in the north, centre and southwest of the country, and a less prestigious variety spoken elsewhere.

In the far south, especially in towns such as Nhlangano and Hlatikhulu, the variety of the language spoken is significantly influenced by isiZulu. Many Swazis (plural emaSwati, singular liSwati), including those in the south who speak this variety, do not regard it as 'proper' Swazi. This is what may be referred to as the second dialect in the country. The sizeable number of Swazi speakers in South Africa (mainly in the Mpumalanga province, and in Soweto) are considered by Eswatini Swazi speakers to speak a non-standard form of the language.

Unlike the variant in the south of Eswatini, the Mpumalanga variety appears to be less influenced by Zulu, and is thus considered closer to standard Swazi. However, this Mpumalanga variety is distinguishable by distinct intonation, and perhaps distinct tone patterns. Intonation patterns (and informal perceptions of 'stress') in Mpumalanga Swazi are often considered discordant to the Swazi ear. This South African variety of Swazi is considered to exhibit influence from other South African languages spoken close to Swazi.

A feature of the standard prestige variety of Swazi (spoken in the north and centre of Eswatini) is the royal style of slow, heavily stressed enunciation, which is anecdotally claimed to have a 'mellifluous' feel to its hearers.

Phonology

Consonants

Swazi does not distinguish between places of articulation in its clicks. They are dental (as [ǀ]) or might also be alveolar (as [ǃ]). It does, however, distinguish five or six manners of articulation and of manner, including tenuis, aspirated, voiced, breathy voiced, nasal, and breathy-voiced nasal.[5]

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Lateral | Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | nasal | plain | nasal | ||||||

| Click | plain | ǀ | ᵑǀ | ||||||

| aspirated | ǀʰ | ᵑǀʰ | |||||||

| breathy | ᶢǀʱ | ᵑǀʱ | |||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ, ŋɡ | |||||

| Stop | ejective | pʼ | tʼ | kʼ, k̬ | |||||

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | ||||||

| breathy | bʱ | dʱ | ɡʱ | ||||||

| implosive | ɓ | ||||||||

| Affricate | voiceless | tf | tsʼ, tsʰ | tʃʼ | kxʼ | ||||

| voiced | dv | dz | dʒʱ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ɬ | ʃ | h | h̃ | ||

| voiced | v | z | ɮ | ʒ | ɦ | ɦ̃ | |||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||||||

The consonants /ts k ŋɡ/ each have two sounds. /ts/ and /k/ can both occur as ejective sounds, [tsʼ] and [kʼ], but their common forms are [tsʰ] and [k̬]. The sound /ŋɡ/ differs when at the beginning of stems as [ŋ], and commonly as [ŋɡ] within words.[5][6][7]

Tone

Swazi exhibits three surface tones: high, mid and low. Tone is unwritten in the standard orthography. Traditionally, only the high and mid tones are taken to exist phonemically, with the low tone conditioned by a preceding depressor consonant. Bradshaw (2003) however argues that all three tones exist underlyingly.

Phonological processes acting on tone include:

- When a stem with non-high tone receives a prefix with underlying high tone, this high tone moves to the antepenult (or to the penult, when the onset of the antepenult is a depressor).

- High spread: all syllables between two high tones become high, as long as no depressor intervenes. This happens not only word-internally, but also across a word boundary between a verb and its object.

The depressor consonants are all voiced obstruents other than /ɓ/. The allophone [ŋ] of /ŋɡ/ appears to behave as a depressor for some rules but not others.[8]

Grammar

Nouns

The Swazi noun (libito) consists of two essential parts, the prefix (sicalo) and the stem (umsuka). Using the prefixes, nouns can be grouped into noun classes, which are numbered consecutively, to ease comparison with other Bantu languages.

The following table gives an overview of Swazi noun classes, arranged according to singular-plural pairs.

| Class | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1/2 | um(u)-1 | ba-, be- |

| 1a/2a | Ø- | bo- |

| 3/4 | um(u)-1 | imi- |

| 5/6 | li- | ema- |

| 7/8 | s(i)-2 | t(i)-2 |

| 9/10 | iN-3 | tiN-3 |

| 11/10 | lu-, lw- | |

| 14 | bu-, b-, tj- | |

| 15 | ku- | |

| 17 | ku- |

1 umu- replaces um- before monosyllabic stems, e. g. umuntfu (person).

2 s- and t- replace si- and ti- respectively before stems beginning with a vowel, e.g. sandla/tandla (hand/hands).

3 The placeholder N in the prefixes iN- and tiN- stands for m, n or no letter at all.

Verbs

Verbs use the following affixes for the subject and the object:

| Person/ Class |

Prefix | Infix |

|---|---|---|

| 1st sing. | ngi- | -ngi- |

| 2nd sing. | u- | -wu- |

| 1st plur. | si- | -si- |

| 2nd plur. | ni- | -ni- |

| 1 | u- | -m(u)- |

| 2 | ba- | -ba- |

| 3 | u- | -m(u)- |

| 4 | i- | -yi- |

| 5 | li- | -li- |

| 6 | a- | -wa- |

| 7 | si- | -si- |

| 8 | ti- | -ti- |

| 9 | i- | -yi- |

| 10 | ti- | -ti- |

| 11 | lu- | -lu- |

| 14 | bu- | -bu- |

| 15 | ku- | -ku- |

| 17 | ku- | -ku- |

| reflexive | -ti- |

Months

Months in Swazi/Swati:

| English | Swazi/Swati |

|---|---|

| January | nguBhimbidvwane |

| February | yiNdlovana |

| March | yiNdlovulenkhulu |

| April | nguMabasa |

| May | yiNkhwekhweti |

| June | yiNhlaba |

| July | nguKholwane |

| August | iNgci |

| September | iNyoni |

| October | iMphala |

| November | Lweti |

| December | yiNgongoni |

Sample text

The following example of text is Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Bonkhe bantfu batalwa bakhululekile balingana ngalokufananako ngesitfunti nangemalungelo. Baphiwe ingcondvo nekucondza kanye nanembeza ngakoke bafanele batiphatse nekutsi baphatse nalabanye ngemoya webuzalwane.[9]

The Declaration reads in English:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood."[10]

References

- Swazi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Webb, Vic (2002). Language in South Africa: The Role of Language in National Transformation, Reconstruction and Development. Impact: Studies in language and society. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 14:78.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Swati". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Jouni Filip Maho, 2009. New Updated Guthrie List Online

- Taljaard, P. C.; Khumalo, J. N.; Bosch, S. E. (1991). Handbook of siSwati. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik.

- Corum, Claudia W. (1991). An Introduction to the Swazi (Siswati) Language. Indiana University.: Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics. pp. 2.7–2.20.

- Ziervogel, Dirk; Mabuza, Enos John (1976). A Grammar of the Swati Language: siSwati. Pretoria: J.L. van Schaik.

- Bradshaw, Mary M. (2003). "Consonant-tone interaction in Siswati". 음성음운형태론연구. 9 (2): 277–294. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "Universal Declaration of Human Rights - Siswati". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Universal Declaration of Human Rights". wikisource.org. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

External links

| Swati edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Look up Swazi in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Swazi phrasebook. |