Simosuchus

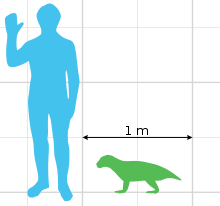

Simosuchus (meaning "pug-nosed crocodile" in Greek, referring to the animal's blunt snout) is an extinct genus of notosuchian crocodylomorphs from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. It is named for its unusually short skull. Fully grown individuals were about 0.75 metres (2.5 ft) in length. The type species is Simosuchus clarki, found from the Maevarano Formation in Mahajanga Province.

| Simosuchus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Display at the Royal Ontario Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Ziphosuchia |

| Genus: | †Simosuchus Buckley et al., 2000 |

| Species | |

| |

The teeth of S. clarki were shaped like maple leaves, which coupled with its short and deep snout suggests it was not a carnivore like most other crocodylomorphs. In fact, these features have led many palaeontologists to consider it a herbivore.

Description

Simosuchus was small, about 0.75 metres (2.5 ft) long based on the skeletons of mature individuals.[1] In contrast to most other crocodyliforms, which have long, low skulls, Simosuchus has a distinctively short snout. The snout resembles that of a pug, giving the genus its name, which means "pug-nosed crocodile" in Greek.[2] The shape of skulls differs considerably between specimens, with variation in ornamentation and bony projections. These differences may be indications of sexual dimorphism. The front (preorbita) portion of the skulll is angled downwards. Simosuchus likely held its head so that the preorbital area was angled about 45° from horizontal. The teeth line the front of the jaws and are shaped like maple leaves. At the back of the skull, the occipital condyle (which articulates with the neck vertebrae) is downturned. 45 autapomorphies, or features unique to Simosuchus, can be found in the skull alone.[3]

In most respects, the postcranial skeleton of Simosuchus resembles that of other terrestrial crocodyliforms. There are several differences, however, that have been used to distinguish it from related forms. The scapula is broad and tripartite (three-pronged). On its surface, there is a laterally directed prominence. The deltopectoral crest, a crest on the upper end of the humerus, is small. The glenohumeral condyle of the humerus, which connects to the pectoral girdle in the shoulder joint, has a distinctive rounded ellipsoid shape. The limbs are robust. The radius and ulna of the forearm fit tightly together. The front feet are small with large claws, and the back feet are also reduced in size. There is a small crest along the anterior edge of the femur. On the pelvis, the anterior process of the ischium is spur-like.[4]

Most of the spinal column of Simosuchus is known. There are eight cervical vertebrae in the neck, at least fifteen dorsal vertebrae in the back, two sacral vertebrae at the hip, and no more than twenty caudal vertebrae in the tail. The number of vertebrae in the tail is less than that of most crocodyliforms, giving Simosuchus a very short tail.[1]

Like other crocodyliforms, Simosuchus was covered in bony plates called osteoderms. These form shields over the back, underside, and tail. Unusually among crocodyliforms, Simosuchus also has osteoderms covering much of the limbs. Osteoderms covering the back, tail, and limbs are light and porous, while the osteoderms covering the belly are plate-like and have an inner structure resembling spongy diploë. Simosuchus has a tetraserial paravertebral shield over its back, meaning that there are four rows of tightly locking paramedial osteoderms (osteoderms to either side of the midline of the back). To either side of the shield, there are four rows of accessory parasagittal osteoderms. These accessory osteoderms tightly interlock with one another.[5]

History

The first specimen of Simosuchus clarki, which served as the basis for its initial description in 2000, included a complete skull and lower jaw, the front of the postcranial skeleton, and parts of the posterior postcranial skeleton. Five more specimens were later described, representing the majority of the skeleton. Many isolated teeth have also been found in the Mahajanga Basin. Most remains of Simosuchus were found as part of the Mahajanga Basin Project, directed by the Université d'Antananarivo and Stony Brook University. Material was usually found in clays that were part of flow deposits in the Anembalemba Member of the Maevarano Formation.[6]

Classification

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Simosuchus was first considered to be a basal member of the clade Notosuchia, and was often considered to be closely related to Uruguaysuchus from the Late Cretaceous of Uruguay and Malawisuchus from the Early Cretaceous of Malawi. Later phylogenetic studies have placed it closer to the genus Libycosuchus and in a more derived position than some other notosuchians such as Uruguaysuchus.[9] In its initial description by Buckley et al. (2000), Simosuchus was placed in the family Notosuchidae. Its sister taxon was Uruguaysuchus, and the two were allied with Malawisuchus. These taxa were placed in Notosuchidae along with Libycosuchus and Notosuchus. Most of the following phylogenetic analyses resulted in a similar placement of Simosuchus and other genera within Notosuchia. Turner and Calvo (2005) also found a clade including Simosuchus, Uruguaysuchus, and Malawisuchus in their study.

The phylogenetic analysis of Carvalho et al. (2004), based on different character values than previous studies, produced a very different relationship among Simosuchus and other notosuchians. Simosuchus, along with Uruguaysuchus and Comahuesuchus, were placed outside Notosuchia. Simosuchus was found to be the sister taxon of the Chinese genus Chimaerasuchus in the family Chimaerasuchidae. Like Simosuchus, Chimaerasuchus has a short snout and was probably herbivorous. Both genera were placed outside Notosuchia in the larger clade Gondwanasuchia. Uruguaysuchus, previously considered to be a basal notosuchian and a close relative of Simosuchus, was placed in its own family, Uruguaysuchidae, also outside Notosuchia. Malawisuchus was found to be a member of Peirosauroidea, specifically a member of the family Itasuchidae.[10]

The following cladogram simplified after a comprehensive analysis of notosuchians which focused on Simosuchus clarki presented by Alan H. Turner and Joseph J. W. Sertich in 2010.[9]

| Notosuchia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

*Note: Based on a specimen that was reassigned from Peirosaurus.[11]

Paleobiology

.jpg)

Simosuchus, like other notosuchians, was fully terrestrial. The short tail would have had little use in swimming.[1] The osteoderm shield was inflexible, restricting lateral movement in Simosuchus as a possible adaptation to an entirely terrestrial lifestyle. Robust legs are also consistent with terrestrial locomotion. The deltopectoral crest on the humerus and the anterior crest on the femur served as attachment points for strong limb muscles. The hindlimbs of Simosuchus were semierect, unlike the fully erect posture of most other notosuchians.

Simosuchus was probably a herbivore; its complex dentition resembles that of herbivorous iguanids.[12]

A fossorial, or burrowing lifestyle, for Simosuchus has recently been proposed but is not widely agreed upon.[3] Evidence for burrowing includes the robust limbs and short snout, which appears shovel-like. There are also areas on the skull that may have attached to strong neck muscles that would have been well suited for burrowing.[13]

Paleobiogeography

It is unknown how Simosuchus arrived in Madagascar. A similar crocodyliform, Araripesuchus tsangatsangana, is also known from the Maevarano Formation, but its relation to Simosuchus is unclear.[14] It has been classified as both a notosuchian and a basal neosuchian in various phylogenetic analyses.[15] Nearly all notosuchians are known from Gondwana, the southern supercontinent that existed throughout much of the Mesozoic and encompassed South America, Africa, India, Australia, and Antarctica. Libycosuchus, regarded as one of the closest relatives of Simosuchus, lived in Egypt. Unresolved relationships among notosuchians along with an incomplete fossil record have made it difficult to determine the biogeographic origins of Simosuchus.

References

- Georgi, J.A.; Krause, D.W. (2010). "Postcranial axial skeleton of Simosuchus clarki (Crocodyliformes: Notosuchia) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (6, Supplement): 99–121. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.519172.

- Buckley, G.A.; Brochu, C.A.; Krause, D.W.; Pol, D. (2000). "A pug-nosed crocodyliform from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Nature. 405 (6789): 941–944. doi:10.1038/35016061. PMID 10879533.

- Kley, N.J.; Sertich, J.J.W.; Turner, A.H.; Krause, D.W.; O'Connor, P.M.; Georgi, J.A. (2010). "Craniofacial morphology of Simosuchus clarki (Crocodyliformes: Notosuchia) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (6, Supplement): 13–98. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.532674.

- Sertich, J.J.W.; Groenke, J.R. (2010). "Appendicular skeleton of Simosuchus clarki (Crocodyliformes: Notosuchia) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (6, Supplement): 122–153. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.516902.

- Hill, R.V. (2010). "Osteoderms of Simosuchus clarki (Crocodyliformes: Notosuchia) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (6, Supplement): 154–176. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.518110.

- Krause, D.W.; Sertich, J.J.W.; Rogers, R.R.; Kast, S.C.; Rasoamiaramanana, A.H.; Buckley, G.A. (2010). "Overview of the discovery, distribution, and geological context of Simosuchus clarki (Crocodyliformes: Notosuchia) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (6, Supplement): 4–12. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.516784.

- Turner, A.H.; Calvo, J.O. (2005). "A new sebecosuchian crocodyliform from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (1): 87–98. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0087:ANSCFT]2.0.CO;2.

- Diego Pol; Juan M. Leardi; Agustina Lecuona & Marcelo Krause (2012). "Postcranial anatomy of Sebecus icaeorhinus (Crocodyliformes, Sebecidae) from the Eocene of Patagonia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (2): 328–354. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.646833.

- Turner, A.H.; Sertich, J.W. (2010). "Phylogenetic history of Simosuchus clarki (Crocodyliformes: Notosuchia) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (6, Supplement): 177–236. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.532348.

- Carvalho, I.S.; Ribeiro, L.C.B.; Avilla, L.S. (2004). "Uberabasuchus terrificus sp. nov., a new Crocodylomorpha from the Bauru Basin (Upper Cretaceous), Brazil" (PDF). Gondwana Research. 7 (4): 975–1002. doi:10.1016/S1342-937X(05)71079-0. ISSN 1342-937X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06.

- Agustín G. Martinelli; Joseph J.W. Sertich; Alberto C. Garrido & Ángel M. Praderio (2012). "A new peirosaurid from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina: Implications for specimens referred to Peirosaurus torminni Price (Crocodyliformes: Peirosauridae)". Cretaceous Research. in press: 191–200. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2012.03.017.

- Melstrom, Keegan; Irmis, Randall (2019-06-01). "Repeated Evolution of Herbivorous Crocodyliforms during the Age of Dinosaurs". Current Biology. 29: 2389–2395.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.076. PMID 31257139.

- Krause, D.W.; O'Connor, P.M.; Rogers, K.C.; Sampson, S.D.; Buckley, G.A.; Rogers, R.R. (2006). "Late Cretaceous terrestrial vertebrates from Madagascar: Implications for Latin American biogeography". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 93 (2): 178–20. doi:10.3417/0026-6493(2006)93[178:LCTVFM]2.0.CO;2.

- Turner, A.H. (2006). "Osteology and phylogeny of a new species of Araripesuchus (Crocodyliformes: Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Historical Biology. 18 (3): 255–369. doi:10.1080/08912960500516112.

- Sereno, P. C.; Larsson, H. C. E. (2009). "Cretaceous crocodyliforms from the Sahara". ZooKeys (28): 1–143. doi:10.3897/zookeys.28.325.