Razanandrongobe

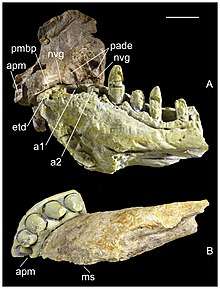

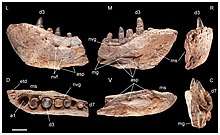

Razanandrongobe (meaning "ancestor [of the] large lizard" in Malagasy) is a genus of carnivorous ziphosuchian crocodyliform from the Middle Jurassic of Madagascar. It contains the type and only species Razanandrongobe sakalavae, named in 2004 by Simone Maganuco and colleagues based on isolated bones found in 2003. The remains, which included a fragment of maxilla and teeth, originated from the Bathonian-aged Sakaraha Formation of Mahajanga, Madagascar. While they clearly belonged to a member of the Archosauria, Maganuco and colleagues refrained from assigning the genus to a specific group because the fragmentary remains resembled lineages among both the theropod dinosaurs and crocodylomorphs.

| Razanandrongobe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype of Razanandrongobe, showing teeth and associated maxillary fragment | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Genus: | †Razanandrongobe Maganuco et al., 2006 |

| Species: | †R. sakalavae |

| Binomial name | |

| †Razanandrongobe sakalavae Maganuco et al., 2006 | |

Further remains (including a premaxilla and lower jawbone) had been discovered as early as 1972, but were not described until 2017 by Cristiano Dal Sasso and colleagues. These remains allowed them to confidently assign Razanandrongobe as the oldest-known member of the Notosuchia, a group of crocodylomorphs, which partially filled a gap of 74 million years in the group's evolutionary history. Razanandrongobe shows a number of adaptations to a diet containing bones and tendons, including teeth with large serrations and bony structures reinforcing its palate and teeth. Measuring 7 metres (23 ft) long, it was the largest member of the Notosuchia and may have occupied a predatory ecological niche similar to theropods.

Discovery and naming

Initial discovery

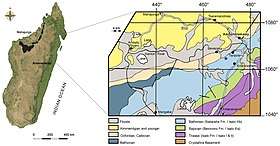

All known remains of Razanandrongobe originate from strata belonging to the Sakaraha Formation in the badlands (locally called tanety) surrounding the town of Ambondromamy, Madagascar. In October 2001, Giovanni Pasini first verified the presence of fossil-bearing strata in this region. During an associated field survey of the locality, local collectors discovered two tooth-bearing skull fragments on the surface of the ground, which belonged to two different kinds of reptiles. These fragments were later acquired by Gilles Emringer and Francois Escuillié from Gannat, France, who intended to make them available for research.[1]

Based on the potential for further research, four temporary permits were obtained in the area for exploration from the Mining Cadastral Office of Madagascar. In April 2003, a joint team from the Milan Natural History Museum (MSNM) and Civic Museum of Fossils of Besano launched a privately-funded expedition to the region. Pasini collected a number of teeth during this expedition. In June 2003, he gained access to one of the two skull fragments, a maxilla, and recognized that the teeth were identical. The MSNM acquired this specimen; it is now catalogued as MSNM V5770, while the teeth are catalogued as MSNM V5771-5777.[1]

Simone Maganuco, Cristiano Dal Sasso, and Pasini described these specimens in 2006 as representing a new genus and species, Razanandrongobe sakalavae, with MSNM V5770 as the holotype. The genus name is a composite of the Malagasy words "razana-" (ancestor), "androngo-" (lizard), and "-be" (large), collectively meaning "ancestor of the large lizard". The species name is Latin for "of Sakalava", referring to the ethnic group which inhabits the region.[1]

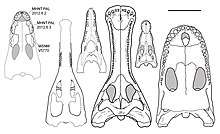

Additional specimens

Between 1972 to 1974, the assistant director of technical services of the Sugar Company of Mahavavy had previously collected a dentary (lower jawbone) and a premaxilla from the area where the holotype of Razanandrongobe was discovered. Under the authorization of the Mines and Energy Directorate of Madagascar, these specimens were exported and stored in the collection of D. Descouens. After they were prepared, these fossils were discovered to pertain to Razanandrongobe; based on the fact that they fit together perfectly, they were further inferred to belong to the same individual. In April 2012, these specimens were acquired by Museum of Natural History of Toulouse (MHNT), where they are respectively catalogued as MHNT.PAL.2012.6.1 and MHNT.PAL.2012.6.2.[2]

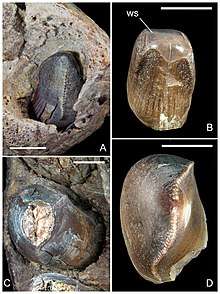

The MHNT also acquired six skull fragments from Descouens, which are catalogued as MHNT.PAL.2012.6.3–8. The source locality of these specimens is unknown. Among these fragments, the larger ones are spongy with pieces of the surrounding rock (matrix) attached; the smaller ones are denser, whitish, and polished, suggesting prolonged exposure to air and sunlight. The MSNM acquired a further specimen, a tooth crown catalogued as MSNM V7144. This specimen had been collected by the Italian agronomist G. Cortenova, who gave the specimen to the amateur entomologist G. Colombo before his death. Colombo donated the specimen to the MSNM. All of these additional specimens were described in 2017 by Dal Sasso, Pasini, Maganuco, and Guillaume Fleury.[2]

Description

Based on available remains, Razanandrongobe is the largest known Jurassic non-marine member of the Mesoeucrocodylia, and the largest member of the Notosuchia overall. In life, the length of its skull likely surpassed that of Barinasuchus, which has been estimated at 88 centimetres (35 in) long.[2][3] Dal Sasso and colleagues inferred a body shape similar to the Baurusuchidae, producing an overall length of 7 metres (23 ft), a height at the hip of 1.6 metres (5 ft 3 in), and a weight of 800–1,000 kilograms (1,800–2,200 lb).[4]

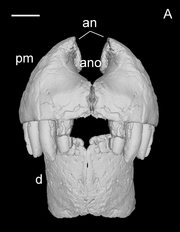

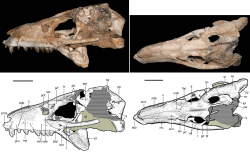

Snout

Razanandrongobe had a highly specialized skull, with a robust and rounded (U-shaped) snout that was taller than it was wide (oreinirostral), like Dakosaurus. At the front of the snout, the openings of the bony nostrils, the apertura nasi ossea, faced forward, and were fused at the midline. Smooth depressions known as the perinarial fossae extended down from the nostrils to the level of the teeth. The remainder of the premaxilla had a roughened surface, covered in crests, ridges, and pits. On the palate, two sub-circular depressions were situated near the front of the snout, where the first pair of teeth from the lower jaw would have been located when the mouth was closed. The palatal portion of the maxilla did not close off the bottom edge of the premaxillae, leaving a large opening —- the incisive foramen —- which was about half as long as the premaxilla was wide.[2]

Like its premaxilla, the maxilla of Razanandrongobe was tall and robust. The surface of the palate, which was thickest below the eye sockets, was placed unusually high above the tooth row, at about halfway up the depth of the tooth sockets. At this position, it met the portion of the palate formed by the palatine bones, and bordered the openings known as the suborbital fenestrae. In this way, the palate of Razanandrongobe resembled those of the Ziphosuchia, including Araripesuchus. On the interior of the maxilla, there was a smooth groove, which may have corresponded to a pneumatic opening in the skull that is also seen in the modern Alligator. The inside of the tooth row on the premaxilla and maxilla bore a paradental shelf covered in ridges and furrows.[2]

Lower jaw

The lower jaw of Razanandrongobe was also tall and robust. Uniquely, the tip of the lower jaw was devoid of teeth, for a section of the dentary corresponding to the diameter of more than one tooth. The front of the jaw would have been fused; on the inside of the bone, there was a scar running along the rear 20% of the fused portion, representing the attachment of the splenial bone. The tip of the lower jaw would have been strengthened by being upturned at an angle of about 50°. Like the premaxilla, the outer surface of the dentary was textured, bearing a dense network of zigzagging canals for blood vessels (i.e., vascular canals). On the interior surface, immediately adjacent to the tooth row, there was a row of pits, which were enclosed by a groove towards the back of the jaw. The top margin of the bone was convex at the front, followed by a concave region behind it.[2]

Teeth

Razanandrongobe had five teeth in each premaxilla, at least ten in each maxilla, and eight in each half of the dentary. Most of the tooth sockets were sub-circular, although the inner half of the sockets in the maxilla and the front of the dentary were rectangular. All of them were wider than they were long, and were nearly vertical. Larger sockets were separated by narrower distances than smaller teeth, with the separating surfaces being ornamented like the paradental shelves. The teeth themselves are unusual; they bear large serrations on both the front and rear edges, which are proportionally even larger than those of dinosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus. They were also thick, non-constricted, and slightly recurved (pachydont). Several types of teeth are present, making Razanandrongobe heterodont: the teeth at the front of the jaw were U-shaped (or salinon-shaped) in cross-section, while those on the sides were incisiform (incisor-like) and sub-oval in cross-section, with the smallest teeth at the rear being globe-shaped. The smallest teeth were globe-shaped. None of the teeth were particularly hypertrophied like the canine teeth of mammals (i.e., caniniform), but the first three dentary teeth were larger than the rest.[1][2]

Classification

Archosaurian affinities

In 2006, Maganuco and colleagues identified Razanandrongobe as a member of the Archosauriformes by its serrated teeth and the thecodont condition of its teeth (i.e. their deep implantation in tooth sockets). Both characteristics are widespread among archosauriforms,[5] and Maganuco and colleagues suggested that the former is a synapomorphy (shared specialization) of the group. They also noted that Razanandrongobe possessed unfused interdental plates covering the inner (lingual) surface of its teeth; they are absent in the non-archosauriform archosauromorphs, present but unfused in several lineages among the Archosauriformes, and fused in some theropod dinosaurs.[6] Maganuco and colleagues suggested that unfused interdental plates are either a synapomorphy of Archosauriformes, or a plesiomorphic (ancestrally present) characteristic of crocodyliforms, theropods, and poposaurids.[1][7]

Considering these characteristics, Maganuco and colleagues placed Razanandrongobe in the Archosauria, but not as part of any basal (early-diverging) lineages due to its heterodont teeth and tall maxilla. While it resembles the Prestosuchidae in the depth and shape of its maxilla, heterodont teeth, paradental shelves, and large size, Maganuco and colleagues considered these traits to have been convergently acquired. Within the Archosauria, they identified two possible positions for Razanandrongobe: Crocodylomorpha and Theropoda, the only lineages of large predatory archosaurs to have survived past the Triassic. However, the original material of Razanandrongobe, consisting of a maxilla and teeth, was too fragmentary to be included in a phylogenetic analysis of archosauriforms, since it lacks nearly all characteristics used in such analyses.[1]

.jpg)

Among crocodylomorphs, Maganuco and colleagues demonstrated that Razanandrongobe had characteristics intermediate between the basal evolutionary grade "Sphenosuchia" (which is not a proper clade) and the derived Mesoeucrocodylia: the maxilla would have bordered both the internal choanae (nostril openings, like "sphenosuchians") and the suborbital fenestrae (like mesoeucrocodylians); the antorbital fenestrae would have had a narrower front margin and were retracted further back on the skull than "sphenosuchians"; and the paradental shelf was more developed than "sphenosuchians". Its vertical tooth sockets resembled "sphenosuchians", baurusuchians, sebecosuchians, and peirosaurids, while the positioning of the palatal depressions and the globe-shaped teeth particularly resembled peirosaurids (though these teeth bear "necks" in peirosaurids). However, the height of the paradental shelf, the large tooth serrations, the width of the teeth from the side of the jaw, and the relatively flat interdental plates were found to be unusual for crocodylomorphs.[1]

Among theropods, Maganuco and colleagues likened the sub-rectangular tooth sockets, roughened interdental plates, low-crowned teeth, and possible broad contact between the maxilla and jugal in Razanandrongobe to the Abelisauridae; however, they noted that the innervated pits (foramina) on its maxilla were distributed more evenly, and that its teeth differed in their cross-sections and the size of their serrations. Meanwhile, the teeth at the front of its jaw resembled the Tyrannosauridae in its shape and cross-section, and the teeth at the sides of the jaw were thickened similarly (or even further), but the serrations on the teeth were larger and lacked a characteristic groove running across them, and its paradental shelf was larger than tyrannosaurids. Finally, while spinosaurids had a well-developed paradental shelf and thickened teeth, the known spinosaurids at the time were all highly specialized, with palatal shelves that formed the "roof" of the mouth at an acute angle, sub-circular tooth sockets, and teeth that were non-heterodont, high-crowned, and unserrated.[1]

Resolution as a ziphosuchian

Given the incompleteness of Razanandrongobe, Maganuco and colleagues did not assign Razanandrongobe to a specific group in 2006. Subsequently, the discovery of additional specimens allowed Dal Sasso and colleagues to refine the phylogenetic placement of Razanandrongobe in 2017. The new specimens allowed them to unequivocally identify it as a crocodylomorph and not a theropod, with all similarities having been convergently acquired. Unlike theropods, it has forward-facing and fused bony nostrils that do not contact the maxilla anywhere and are not divided by any bony process; a dentary taller and more robust than any theropod; a splenial which would have been a conspicuous part of the lower jaw, being even visible from the side; a well-developed bony palate on the maxilla; and the previously-noted thickening of the tooth crowns. They also noted another difference from spinosaurids in that the bony nostrils were not retracted up the length of the snout.[2]

Within the Crocodylomorpha, Dal Sasso and colleagues confirmed previous observations that the palate of Razanandrongobe differed from "sphenosuchians", in addition to having a more robust dentary with a shorter toothless portion and a less conspicuous splenial. In particular, the extent of the splenial was probably similar to many other notosuchians, but was not as extreme as the Peirosauridae where the bone contributes to half of the jaw. The fused bony nostrils were most similar in morphology and orientation to the Sphagesauridae; they differed from the Peirosauridae in their complete fusion, and from the Sebecidae in their orientation forwards and not upwards. Its perinarial fossa was a common characteristic among mesoeucrocodylians, and it also lacked a notch in the upper jaw to receive an enlarged lower caniniform tooth; both characteristics were likely plesiomorphic for the group Notosuchia.[2]

In Razanandrongobe, the incisive foramen was larger than most mesoeucrocodylians, while the robust palate on the maxilla was more typical. The upturning of the dentary was most like Baurusuchidae and Kaprosuchus, but Uruguaysuchus and Peirosauridae also had dentaries that tapered upwards in an arch. Unlike Uruguaysuchus, the tooth sockets were not fused. Unlike Aplestosuchus and Sebecus, the teeth were not constricted at the base, nor did the first tooth project forwards. While some baurusuchids and sebecids had serrated teeth, their teeth were flattened, and the serrations were much smaller. No notosuchian had sub-oval teeth like Razanandrongobe, but some sphagesaurids had sub-conical teeth.[2]

A phylogenetic analysis conducted by Dal Sasso and colleagues, based on that of Lucas Fiorelli and colleagues in 2016,[8] found that Razanandrongobe was a member of the Ziphosuchia, closely related to Sebecosuchia. The former relation was supported by the lack of constricted tooth crowns and the contact between the dentary and splenial, while the latter was supported by the deep dentary, the similarly-sized and symmetrical serrations, the concavity of the dentary, and a dip in the dentary below the level of the tooth sockets at the middle of the tooth row. Their resulting phylogenetic tree (the majority-rule consensus tree) is partially reproduced below.[2]

| Notosuchia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolutionary context

Little is known about the origins and early evolution of notosuchians, but the fact that they are the sister group of the Neosuchia (which contains all living crocodilians) in the Mesoeucrocodylia implies that they must have first appeared during the Jurassic. Prior to the recognition of Razanandrongobe as a notosuchian, the oldest-known notosuchians were the Aptian-aged (Cretaceous) Anatosuchus, Candidodon, Malawisuchus, and Uruguaysuchus, leaving a ghost lineage of 74 million years between the group's presumed origin and its oldest members.[2]

The phylogenetic position of Razanandrongobe in the Notosuchia makes it the oldest-known representative of the group. Razanandrongobe predates all of these notosuchians by 42 million years, partially filling the ghost lineage. Its retention of plesiomorphic characteristics is consistent with its status as an early notosuchian; however, for this reason, Dal Sasso and colleagues noted that its close relation to Sebecosuchia — a much younger lineage, being known from the Santonian forward — must be treated as provisional. Dal Sasso and colleagues supported the notion that notosuchians primarily lived on the continent of Gondwana through their evolutionary history (although the remaining ghost lineage prior to Razanandrongobe precludes inferences about their origins).[2]

Palaeobiology

In 2006, Maganuco and colleagues analyzed wear patterns on the surface of Razanandrongobe's teeth. For the teeth at the sides of the jaw, most of the wear is present on the outer (lingual) surface of the teeth, on which a U-shaped chip is present on the top third of the crown. There is also a thinner chip on the front (mesial) edge of the tooth, flattening some of the serrations. By contrast, for the teeth at the front of the jaw, the wear is more present on the inner (labial) surface. They inferred that these wear surfaces more strongly resemble those resulting from tooth-food contact than from tooth-tooth contact, with the enamel having flaked off as the animal bit into bones or other hard objects,[1] based on similar observations for tyrannosaurids.[9]

Skull anatomy also supports a diet for Razanandrongobe that included hard tissues like bones and tendons. Like tyrannosaurids, the serrations on the teeth of Razanandrongobe were adapted to biting into bone in terms of their size, shape, and also the presence of a rounded depression at the base between neighbouring serrations. In tyrannosaurids, the latter was inferred to have distributed force over the serrations and prevented cracks from spreading, or possibly to have gripped meat fibres.[10] The incisiform teeth of Razanandrongobe also resembles the bone-scraping teeth on the premaxillae of tyrannosaurids, and the teeth at the sides of the jaw were similarly reinforced through thickening (though to an even greater extent). The rest of the skull would have been strengthened by the expansion of the paradental shelves to form a "secondary palate", which would have greatly increased resistance to vertical bending and torsion,[11] while the fused interdental plates would have protected the teeth from transverse forces.[1][12] In 2017, Dal Sasso and colleagues suggested that these feeding adaptations — along with a large skull and body size — made Razanandrongobe a highly-specialized terrestrial predator. They inferred that it could have competed with and occupied the ecological niches of theropods in the local ecosystem.[2]

Palaeoecology

The strata from which Razanandrongobe fossils were recovered has been referred to as the "Facies Continental" or "Bathonien Facies Mixte Dinosauriens" (Bathonian mixed dinosaurian facies) of the Sakaraha Formation (or the Isalo IIIb Formation) in the Isalo Group. This geological formation consists of cross-bedded layers of sandstone and siltstone with "calcareous paves" and multi-coloured claystone banks. The sandstone surrounding the holotype of Razanandrongobe is fine-grained (0.2–0.3 millimetres (0.008–0.01 in) in diameter) and is mainly composed of quartz, with rarer grains of ilmenite, garnet, and zircon. The depositional environment has been inferred to be fluvial (river-based) or lacustrine (lake-based).[1][2]

Based on the sea urchins Nucleolites amplus and Acrosalenia colcanapi as index fossils, the Sakaraha Formation has been correlated to the Bathonian stage (167.7–164.7 million years ago) of the Middle Jurassic epoch. Middle Jurassic deposits in the Mahajanga Basin have produced an unusual but poorly-known assemblage of animals. In 2005, the other skull fragment found in the same locality as Razanandrongobe was named as the sauropod dinosaur Archaeodontosaurus.[13] Teeth of pterosaurs were also found at the locality.[14] Animals from other localities include the sauropods Lapparentosaurus and "Bothriospondylus" madagascariensis, and another sauropod based on teeth;[15] theropods of the groups Abelisauridae, basal Ceratosauria, Coelurosauria, and possibly Tetanurae, along with tracks of the ichnogenus Kayentapus;[16][17][18] thalattosuchian crocodyliforms; a mammal belonging to the Tribosphenida;[19] plesiosaurs; and possibly ichthyosaurs. Silicified wood is also present in the strata.[1][2]

References

- Maganuco, S.; Dal Sasso, C.; Pasini, G. (2006). "A new large predatory archosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Madagascar". Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale in Milano. 147 (1): 19–51.

- Dal Sasso, C.; Pasini, G.; Fleury, G.; Maganuco, S. (2017). "Razanandrongobe sakalavae, a gigantic mesoeucrocodylian from the Middle Jurassic of Madagascar, is the oldest known notosuchian". PeerJ. 5: e3481. doi:10.7717/peerj.3481. PMC 5499610. PMID 28690926.

- Molnar, R.E. (2013). "Cenozoic dinosaurs in South America revisited". Abstracts with Programs. 47th Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America. 45 (3). San Antonio: Geological Society of America. p. 83.

- "Giant croc had teeth like a T. rex". BBC News. BBC. July 4, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Sereno, P.C. (1991). "Basal Archosaurs: Phylogenetic Relationships and Functional Implications". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 11 (S4): 1–53. doi:10.1080/02724634.1991.10011426.

- Juul, L. (1994). "The phylogeny of basal archosaurs". Palaeontologia Africana. 31: 1–38.

- Nesbitt, S.J. (2011). "The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origin of Major Clades". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292. doi:10.1206/352.1.

- Fiorelli, L.E.; Leardi, J.M.; Hechenleitner, E.M.; Pol, D.; Basilici, G.; Grellet-Tinner, G. (2016). "A new Late Cretaceous crocodyliform from the western margin of Gondwana (La Rioja Province, Argentina)". Cretaceous Research. 60: 194–209. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.12.003.

- Schubert, B.W.; Unger, P.S. (2005). "Wear facets and enamel spalling in tyrannosaurid dinosaurs". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 50 (1): 93–99.

- Abler, W.L. (2001). "A kerf-and-drill model of tyrannosaur tooth serrations". In Tanke, D. H.; Carpenter, K. (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Life of the Past. Indiana University Press. pp. 84–89. ISBN 9780253339072.

- Busbey, A.B. (1995). "The structural consequences of skull flattening in crocodilians". In Thomason, J.J. (ed.). Functional Morphology in Vertebrate Paleontology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 173–192. ISBN 9780521629218.

- Senter, P. (2003). "New information on cranial and dentary features of the Triassic archosauriform reptile Euparkeria capensis". Palaeontology. 46 (3): 613–621. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00311.

- Buffetaut, E. (2005). "A new sauropod dinosaur with prosauropod-like teeth from the Middle Jurassic of Madagascar". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 176 (5): 467–473. doi:10.2113/176.5.467.

- Dal Sasso, C.; Pasini, G. (2003). "First record of pterosaurs (Pterosauria, Archosauromorpha, Diapsida) in the Middle Jurassic of Madagascar". Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale in Milano. 144 (2): 281–296.

- Bindellini, G.; Dal Sasso, C. (2019). "Sauropod teeth from the Middle Jurassic of Madagascar, and the oldest record of Titanosauriformes". Papers in Palaeontology: 1–25. doi:10.1002/spp2.1282.

- Maganuco, S.; Cau, A.; Pasini, G. (2005). "First description of theropod remains from the Middle Jurassic (Bathonian) of Madagascar". Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale in Milano. 146 (2): 165–202.

- Maganuco, S.; Cau, A.; Dal Sasso, C.; Pasini, G. (2007). "Evidence of large theropods from the Middle Jurassic of the Mahajanga Basin, NW Madagascar, with implications for ceratosaurian pedal ungual evolution". Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale in Milano. 148 (2): 261–271.

- Wagensommer, A.; Latiano, M.; Leroux, G.; Cassano, G.; D'Orazi Porchetti, S. (2011). "New dinosaur tracksites from the Middle Jurassic of Madagascar: ichnotaxonomical, behavioural and palaeoenvironmental implications". Palaeontology. 55 (1): 109–126. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01121.x.

- Flynn, J.J.; Parrish, J.M.; Rakotosaminanana, B.; Simpson, W.F.; Wyss, A.R. (1999). "A Middle Jurassic mammal from Madagascar". Nature. 401: 57–60. doi:10.1038/43420.

External links

- Razanandrongobe sakalavae - Dinosaur Mailing List posting that announces the genus and includes the abstract of Maganuco et al.'s article.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Razanandrongobe. |