Semisulcospira libertina

Semisulcospira libertina is a species of freshwater snail with an operculum, an aquatic gastropod mollusk in the family Semisulcospiridae. Widespread in east Asia, it lives in China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and the Philippines. In some countries it is harvested as a food source. It is medically important as a vector of clonorchiasis, paragonimiasis, metagonimiasis and others.

| Semisulcospira libertina | |

|---|---|

| |

| S. libertina partially covered by detritus, but showing its basal cords, an important identifying feature | |

| |

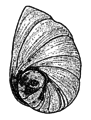

| Drawing of an apertural view of an S. libertina shell | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | S. libertina |

| Binomial name | |

| Semisulcospira libertina | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

|

Melania libertina Gould, 1859 | |

Taxonomy

The type specimens were collected by American scientist William Stimpson during the North Pacific Exploring and Surveying Expedition (1853–1856).[3] This species was originally described under the name Melania libertina by American malacologist Augustus Addison Gould in 1859.[3] The specific name libertina is from Latin language and means a "freedwoman". Semisulcospira libertina is the type species of the genus Semisulcospira by subsequent designation.

Kuroda (1963)[5] and Habe (1965)[6] considered S libertina a synonym of Semisulcospira bensoni.[7]

The "S. libertina species complex" consist of three species: S. libertina, S. reiniana and S. kurodai, according to Davis (1969).[7] Placement of S. kurodai within this species complex was confirmed by Oniwa and Kimura in 1986.[8]

Distribution

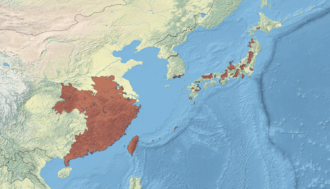

This species occurs in:

- South Korea: continental South Korea and Jeju Island.[9]

- Central China: Hubei, East China: Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Zhejiang and South China: Guangdong.[2]

- Taiwan[2][10]

- widespread in Japan[2][11] It is the most common freshwater snail in Japan.[12]

- This species was also reported from the Philippines.[13]

The type locality was listed as "Simoda and Ousima" by Gould in 1859, that means two localities: Shimoda City in Honshu and Amami Ōshima in Ryukyu Islands.[3][7] Davis (1979) identified the presumed type locality Inozawa River, Inozawa Section, Shimoda City, Izu Peninsula, Shizuoka Prefecture, Honshu. (Site 1 in Figure 4.)[7]

Miura et al. (2013)[12] studied mitochondrial haplotypes of Semisulcospira libertina from Korea and from Japan. Mixed haplotypes in Korea suggest long-distance palaeo-migration across the Korea Strait from Japan to Korea.[12]

Shells of Semisulcospira libertina were also found in the Nojiri-ko Formation at the Lake Nojiri in Central Japan from the age of 27,000 years BP.[1]

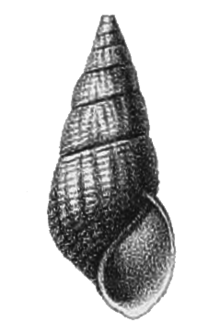

Description

The shell has 4–6 whorls, while the apex of the shell is usually eroded.[7] The spire is long.[14] The aperture is continuous and the apertural lip is simple.[14] Umbilicus is closed.[14] The shell of Semisulcospira libertina is very variable.[7][15] There are seven or more (up to 12) basal cords (spiral sculptures at the base of the body whorl).[7] There are sometimes transverse ribs present on the shell sculpture: 12–18 ribs per penultimate whorl.[7] Periostracum is smooth.[14] The color of the shell is usually light yellow, but it can be light brown very rarely.[7] The spire is darker yellowish-brown.[7] Number of shells is banded with purple brown spiral bands, either with one band, two bands, or three bands.[7]

The average width of the shell of Semisulcospira libertina is 11.0 millimetres (0.43 in) – 13.0 millimetres (0.51 in).[7] The average height of the shell is 26.0 millimetres (1.02 in) – 28.6 millimetres (1.13 in) in Japan.[7]

In Korea, the average width of the shell of Semisulcospira libertina is 12.55–19.37 mm.[16] The average height of the shell is 6.44–9.20 mm.[16] The average total wet weight is 0.24–0.86 g.[16] The average weight of the shell is 0.16–0.62 g.[16] The average weight of the meat is 0.09–0.39 g.[16]

The extrema dimensions were measured in another locality in Korea: The total wet weight ranges from 0.30 g (shell height 9.87 mm) to 1.55 g (shell height 22.57 mm).[17]

Mineral composition of the shell of this species is as follows: 52.9% CaO, 0.77% SiO2, 0.36% Na2O, 0.06% Al2O3, 0.05% Fe2O3, 0.01% MgO and 0.01% P2O5.[18] There is 45.44% of citrulline of free amino acids (amino acids in blood).[19]

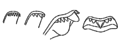

Nelson Annandale depicted the operculum and radula of this species in 1924.[20] Ko et al. (2001)[21] described the radula of this species in detail. The shape of the operculum is ovate and the profile of the shape of the operculum is flat.[14] Coiling of the operculum is paucispiral.[14] Nucleus of the operculum is eccentric.[14]

Cephalic tentacles are short (approximately the same size as the length of the snout).[14]

The reproductive system in a male has the following parts: testis, vas deferens, the spermatophore organ.[22] There is no penis.[22] The reproductive system in a female has the following parts: ovary, the pallial oviduct, the spermatophore bursa, the seminal receptacle and the brood pouch.[22][23]

The diploid chromosome number of Semisulcospira libertina is 2n=36.[7][24] The complete mitochondrial genome of Semisulcospira libertina is known since 2015.[25] Its length is 15,432 bp.[25] It was the first mitochondrial genome resolved within the whole superfamily Cerithioidea.[25]

Semisulcospira reiniana is very similar species: its embryos are larger and embryos are with ribs, adult shells are more slender, 2n=40.[7]

Drawing of an apertural view of a shell of Semisulcospira libertina.

Drawing of an apertural view of a shell of Semisulcospira libertina. Drawing of a lateral view of a shell of Semisulcospira libertina.

Drawing of a lateral view of a shell of Semisulcospira libertina. Drawing of an operculum of Semisulcospira libertina.

Drawing of an operculum of Semisulcospira libertina. Drawing of radular teeth of Semisulcospira libertina

Drawing of radular teeth of Semisulcospira libertina

Ecology

Habitat

Habitats of Semisulcospira libertina include pools, slow flowing rivers, drainage ditches, rice paddies,[7] streams.[20] Kim (1970) studied the habitat of Semisulcospira libertina in Korea.[26] The water temperature is 1.3–22.5 °C.[16]

The pollution tolerance value is 3 (on scale 0–10; 0 is the best water quality, 10 is the worst water quality).[10]

High concentration of cadmium may affect behavior of this species.[27]

Feeding habits

Semisulcospira libertina is polyphagous species[28] and a grazer.[29] It feeds mainly on phytoplankton and detritus.[30] Chemoautotrophic bacteria are probable food source of Semisulcospira libertina, because δ13C and δ34S values were lower than in other invertebrates on the site.[29]

There are 0.032 mg/g of carotenoids in the body of Semisulcospira libertina (shell exclude).[30] Carotenoids composition include: β-Carotene 45%, lutein 13%, zeaxanthin 12%, canthaxanthin 6.5%, (3S,3'S)-astaxanthin 6.5%, (3S)-adonirubin, echinenone 3%, α-Carotene 2%, (3S,3'R)-adonixanthin 1%, fritschiellaxanthin 0.5%, traces of diatoxanthin, fucoxanthin, fucoxanthinol, and other carotenoids 4.5%.[30] Beta-carotene is probably originated from green algae and from cyanobacteria. Lutein is from green algae. Zeaxanthin is from cyanobacteria. Other non-trace carotenoids are probably their oxidative metabolites.[30]

Life cycle

Semisulcospira libertina is gonochoristic, which means that each individual animal is distinctly male or female.[14] Semisulcospira libertina is ovoviviparous.[2][31] The whole larval development occur in the brood pouch of the female. Egg develops into the trochophore, preveliger, veliger, and to the juvenile.[16] There is much of yolk in the embryo.[31] The development from the egg to the veliger lasts 17 days in the temperature 25 ℃.[31] The full development lasts about 8 months in winter and about 2 months in summer.[32] Embryos are without ribs on the shell, but they usually have 1–2 spiral cords.[7] The color of embryo is brown, sometimes yellow.[7]

The female has over 80 small embryos in its brood pouch.[7] Average number of embryos is 58–124 embryos in July.[16] Average number of embryos is 222–570 embryos in November.[16] A single female will usually gave birth to about 607–858 during one year.[33] Recorded maximum was 1535 newborn snails in one year.[33]

Female gave birth to newborn snails in temperature from 12 ℃ to 24 ℃.[33] Birth of snails occur mainly in two periods: in March–May and in September–October.[16] Newborn snails have a width of the shell 0.60–0.99 mm (maximum 1.22 mm).[33] The height of a shell of a newborn snail is up to 1.73 mm.[33] The shell of newborn snails has 2.0–3.5 whorls.[33] The life span is about 2 years.[34]

Parasites

Parasites of Semisulcospira libertina include the following flukes. Some of them are medically important:

- Opisthorchiidae: Semisulcospira libertina serves as the first intermediate host for Clonorchis sinensis in China.[4]

- Paragonimidae: Semisulcospira libertina serves as the first intermediate host for Paragonimus westermani.[2]

- Heterophyidae: Semisulcospira libertina serves as the first intermediate host for Metagonimus miyatai[35][36] and Metagonimus yokogawai.[36]

- Heterophyidae: Semisulcospira libertina serves as the first intermediate host for Centrocestus armatus[37] and Centrocestus formosanus.[38]

- Philopthalmidae: Cercariae of Philophthalmus sp. were found in Semisulcospira libertina in Japan.[39]

- Liolopidae: Semisulcospira libertina serves as the first intermediate host for Liolope copulans.[40]

- Derogenidae: Cercariae of Genarchopsis goppo were found in Semisulcospira libertina in Japan.[41]

- Lecithodendriidae: Semisulcospira libertina serves as the first intermediate host for Acanthatrium hitaensis.[42]

Shinagawa et al. (2001) studied the metabolism and activity of Semisulcospira libertina infected by trematodes.[43]

Bacteria Neorickettsia risticii was detected in cercaria from Semisulcospira libertina in Korea.[44]

Predators

Predators of Semisulcospira libertina include fireflies,[45] such as aquatic larvae of firefly Luciola cruciata.[46]

Human use

Culinary

Pre-packaged Semisulcospira libertina snails sold in Korea | |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Saturated | 28.7% of fat |

| Monounsaturated | 35.5% of fat |

| Polyunsaturated | 35.8% of fat |

% of amino acids / % of free amino acids | |

| Tryptophan | / 0.22% |

| Threonine | 5.4% / 1.87% |

| Isoleucine | 4.6% / 0.06% |

| Leucine | 8.6% / 6.96% |

| Lysine | 6.9% / 2.87% |

| Methionine | 2.1% / 0.25% |

| Cystine | 1.2% / 1.92% |

| Phenylalanine | 4.4% / 0.0% |

| Tyrosine | 3.0% / 0.96% |

| Valine | 5.4% / 0.68 % |

| Arginine | 7.0% / 0.82% |

| Histidine | 2.4% / 0.35% |

| Alanine | 6.9% / 9.39% |

| Aspartic acid | 11.1% / 0.0% |

| Glutamic acid | 14.9% / 0.06% |

| Glycine | 6.6% / 2.77% |

| Proline | 5.1% / 0.52% |

| Serine | 4.4% / 0.09% |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 280% 2240 μg13% 1440 μg800[30] μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 19% 194.5 mg |

| Iron | 8% 1.1 mg |

| Phosphorus | 2% 16.4 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 81.0 g |

| Crude fat | 1.2 g |

| Crude protein | 11.9 g |

| Crude ash | 1.9 g |

| Chlorophyll | 170 mg[19] |

For 100 g of meat there would be need ~250–1000 snails. | |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. | |

Korea

In Korean cuisine, daseulgi-guk (다슬기국) is a type of guk (soup) made with Semisulcospira libertina.

Medicinal

Korea

This species is used as medicinal species in traditional medicine practices on gastrointestinal disorders in Korea.[47] Juice, panbroiled, powder, and simmer from the whole Semisulcospira libertina is used for cure of gastroenteric trouble in Jirisan National Park, Korea.[47] Simmer from the whole Semisulcospira libertina is used for cure of indigestion in Jirisan National Park.[47] Semisulcospira libertina is also used as clear soup with flour dumplings, infusion, juice, soup or as simmer for cure liver-related ailments in traditional medicine in the Southern Regions of Korea.[48]

The non-intentional exposure to shell powder from this species caused the first reported silicosis of such origin in 2012.[18]

References

- (in Japanese) Matsuoka K. & 野尻湖貝類グループ (1982) (Fossil Mollusc Research Group for Noiiri-ko Excavation). "野尻湖層産カワニナ胎児殼化石について : 現生カワニナとの比較研究 "On the fossil embryonic shell of Semisulcospira libertina (GOULD) (Mesogastropoda: Pleuroceridae) from the latest Pleistocene Nojiri-ko Formation, Nagano Prefecture, Central Japan: A comparative study of recent and fossil Semisulcospira". 地球科學 Chikyu kagaku [Earth science] 36(4), 175–184. CiNii.

- Madhyastha A. (2014). "Semisulcospira libertina". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version e.T166281A1127046. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 10 November 2015.

- Gould A. A. (1859). "Descriptions of shells collected in the North Pacific Exploring Expedition under Captain Ringgold and Rodgers". Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History 7: 40-45. page 42.

- World Health Organization (1995). Control of Foodborne Trematode Infection. WHO Technical Report Series. 849. PDF part 1, PDF part 2. page 125.

- (in Japanese) Kuroda T. (1963). A catalogue of the non-marine mollusks of Japan including the Okinawa and Ogasawara Islands. Malacological Society of Japan, Tokyo, 71 pp.

- Habe T. (1965). Gastropoda, in the New Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Fauna of Japan. Hokuryu-Kan Pub. Co., Tokyo, 14-208 pp.

- Davis G. M. (1969). "A taxonomic study of some species of Semisulcospira in Japan (Mesogastropoda: Pleuroceridae)". Malacologia 7: 211-294.

- Oniwa, K.; Kimura, M. (1986). "Genetic variability and relationships in six snail species of the genus Semisulcospira". The Japanese Journal of Genetics. 61 (5): 503–514. doi:10.1266/jjg.61.503.

- Noseworthy, R. G.; Lim, N.-R.; Choi, K.-S. (2007). "A Catalogue of the Mollusks of Jeju Island, South Korea". Korean Journal of Malacology. 23 (1): 65–104.

- Young, S.-S.; Yang, H.-N.; Huang, D.-J.; Liu, S.-M.; Huang, Y.-H.; Chiang, C.-T.; Liu, J.-W. (2014). "Using Benthic Macroinvertebrate and Fish Communities as Bioindicators of the Tanshui River Basin Around the Greater Taipei Area — Multivariate Analysis of Spatial Variation Related to Levels of Water Pollution". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11 (7): 7116–7143. doi:10.3390/ijerph110707116. PMID 25026081.

- Oniwa, K.; Kimura, M. (1986). "Genetic variability and relationships in six snail species of the genus Semisulcospira". The Japanese Journal of Genetics. 61 (5): 503–514. doi:10.1266/jjg.61.503.

- Miura, O.; Köhler, F.; Lee, T.; Li, J.; Foighil, D. Ó. (2013). "Rare, divergent Korean Semisulcospira spp. mitochondrial haplotypes have Japanese sister lineages". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 79 (1): 86–89. doi:10.1093/mollus/eys036.

- Zhong, H.; Cabrera, B. D.; He, L.; Xu, Z.; Lu, B.; Cao, W.; Gao, P. (1982). "Study of lung flukes from Philippines: --a preliminary report". Scientia Sinica. Series B, Chemical, Biological, Agricultural, Medical & Earth Sciences. 25 (5): 521–530. PMID 7100903.

- Strong, E. E.; Colgan, D. J.; Healy, J. M.; Lydeard, C.; Ponder, W. F.; Glaubrecht, M. (2011). "Phylogeny of the gastropod superfamily Cerithioidea using morphology and molecules". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 162 (1): 43–89. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00670.x.

- Davis, G. M. (1972). "Geographic variation in Semisulcospira libertina (Mesogastropoda; Pleuroceridae)". Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London. 40 (1): 5–32.

- (in Korean) Chang Y. J., Chang H. J. & Kim J. J. (2001). "Relative Growth of the Melanin Snail, Semisulcospira libertina libertina and Monthly Composition of Larval Stages in its Brood Pouch". Korean Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 34(2): 131–136. abstract with PDF link.

- Yoon, H. S.; Choi, S. D. (2013). "Size-mass relationships for 4 freshwater snails (Gastropoda: Pleuroceridae) from the Guem River in Korea". The Korean Journal of Malacology. 29 (1): 83–85. doi:10.9710/kjm.2013.29.1.83.

- Jung, J. W.; Lee, B. O.; Lee, J. H.; Park, S. W.; Kim, B. M.; Choi, J. C.; Shin, J. W.; Park, I. W.; Choi, B. W.; Kim, J. Y. (2012). "Silicosis Caused by Chronic Inhalation of Snail Shell Powder". Journal of Korean Medical Science. 27 (1): 93–95. doi:10.3346/jkms.2012.27.1.93. PMID 22219621.

- Lim, C. W.; Kim, Y. K.; Kim, D. H.; Park, J. I.; Lee, M. H.; Park, H. Y.; Jang, M. S. (2009). "한국산 다슬기의 식품학적 성분 및 품질특성 Comparison of quality characteristics of melania snails in Korea". Korean Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (in Korean). 42 (6): 555–560. doi:10.5657/kfas.2009.42.6.555.

- Annandale, T. N. "Gastropoda". pages 27–39. In: Annandale T. N. & Prashad B. (1924). "Report on a small collection of molluscs from the Chekiang Province of China"". Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London. 16 (1): 27–49.

- (in Korean) Ko J.-H., Lee J.-S. & Kwon O. K. (2001). "한국산 다슬기 과 7 종의 치설 연구. Study on radulae of seven species of the Family Pleuroceridae in Korea". The Korean Journal of Malacology 17: 105–115. abstract.

- Nakano D. & Nishiwaki S. (1989). "Anatomical and histological studies on the reproductive system of Semisulcospira libertina (Prosobranchia: Pleuroceridae)". Venus 48(4): 263–273. CiNii.

- Prozorova, L. A.; Rasshepkina, A. V. (2005). "On the reproductive anatomy of Semisulcospira (Cerithioidea: Pleuroceridae: Semisulcospirinae)" (PDF). The Bulletin of the Russian Far East Malacological Society. 9: 123–126.

- Park, G.M.; Kim, J.-J.; Chung, P.-R.; Wang, Y.; Min, D.-Y. (1999). "Karyotypes on three species of Chinese mesogastropod snails, Semisulcospira libertina, S. dolichostoma and Viviparus rivularis". Korean Journal of Parasitology. 37 (1): 5–11. doi:10.3347/kjp.1999.37.1.5. PMC 2733912. PMID 10188377.

- Zeng, T.; Yin, W.; Xia, R.; Fu, C.; Jin, B. (2015). "Complete mitochondrial genome of a freshwater snail, Semisulcospira libertina (Cerithioidea: Semisulcospiridae)". Mitochondrial DNA. 26 (6): 897–898. doi:10.3109/19401736.2013.861449. PMID 24409867. S2CID 207546279.

- Kim, C. W. (1970). "Study on the analysis of snails (Semisulcospira libertina), the first intermediate host of Paragonimus westermani in the Haenam area". Korean Journal of Parasitology. 8 (3): 81–89. doi:10.3347/kjp.1970.8.3.81. PMID 12913626.

- (in Japanese) Kang I. J., Nakamura A., Moroishi J., Ishibashi K., Fukuda S., Shimasaki Y. & OSHIMA Y. (1989). "重金属暴露による淡水巻貝カワニナ(Semisulcospira libertina)の行動への影響. Effects of Heavy Metal Compounds on Behavior of Freshwater Snail (Semisulcospira libertina)". Science bulletin of the Faculty of Agriculture, Kyushu University (九州大学大学院農学研究院学芸雑誌) 64(2), 119–123. CiNii. PDF (Japanese with English summary)

- (in Japanese) Ohara T. & Tomiiyama K. (2000). "Niche segregation of coexisting two freshwater snail species, Semisulcospira libertina (Gould) (Prosobranchia: Pleuroceridae) and Clithon retropictus (Martens) (Prosobranchia: Neritidae)". Venus 59(2): 135–147. CiNii.

- Doi, H.; Takagi, A.; Mizota, C.; Okano, J.; Nakano, S.; Kikuchi, E. (2006). "Contribution of Chemoautotrophic Production to Freshwater Macroinvertebrates in a Headwater Stream Using Multiple Stable Isotopes". International Review of Hydrobiology. 91 (6): 501–508. Bibcode:2006IRH....91..501D. doi:10.1002/iroh.200610898.

- Maoka, T.; Ochi, J.; Mori, M.; Sakagami, Y. (2012). "Identification of carotenoids in the freshwater shellfish Unio douglasiae nipponensis, Anodonta lauta, Cipangopaludina chinensis laeta, and Semisulcospira libertina". Journal of Oleo Science. 61 (2): 69–74. doi:10.5650/jos.61.69. PMID 22277890.

- Nakano D. (1990). "A method of embryo culture and an outline of development of the ovoviviparous freshwater snail Semisulcospira libertina (Prosobranchia: Pleuroceridae)". Venus 49: 107–119. CiNii.

- Nakano D. & Izawa K. (1996). "Reproductive biology of Semisulcospira libertina (Prosobranchia: Pleuroceridae) in Iga basin, Mie Prefecture". Venus 55(3): 235–241. CiNii.

- (in Japanese) Takami A. (1991). "カワニナ属 3 種の産仔頻度, 産仔数と新生貝の大きさ [The Birth Frequency, Number and Size of Newborns in the Three Species of the Genus Semisulcospira (Prosobranchia: Pleuroceridae)]". Venus 50(3): 218–232. CiNii.

- (in Japanese) Torigoe K. & Saiga Y. (2002). "広島県東広島市小田山川のカワニナ殻径頻度分布 The frequency distribution of the shell diametere of Semisulcospira libertina (Gould, 1859) living in the Kodasan-river in Higashihiroshima-shi, Hiroshima Prefecture". Bulletin of the Graduate School of Education, Hiroshima University. Part. II, Arts and science education 50: 11-15. PDF.

- Shimazu, T (2002). "Life cycle and morphology of Metagonimus miyatai (Digenea: Heterophyidae) from Nagano, Japan". Parasitology International. 51 (3): 271–280. doi:10.1016/S1383-5769(02)00038-7. PMID 12243781.

- Chai, J.-Y.; Shin, E.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Rim, H.-J. (2009). "Foodborne Intestinal Flukes in Southeast Asia". Korean Journal of Parasitology. 47 (Suppl): S69–S102. doi:10.3347/kjp.2009.47.S.S69. PMC 2769220. PMID 19885337.

- Paller, V. G.; Kimura, D.; Uga, S. (2007). "Infection dynamics of Centrocestus armatus cercariae (Digenea: Heterophyidae) to second intermediate fish hosts". Journal of Parasitology. 93 (2): 436–439. doi:10.1645/GE-997R.1. PMID 17539435. S2CID 34540040.

- Cho, H.-C.; Chung, P.-R.; Lee, K.-T. (1983). "Distribution of medically important freshwater snails and larval trematodes from Parafossarulus manchouricus and Semisulcospira libertina around the Jinyang Lake in Kyongsang-Nam-Do, Korea". Korean Journal of Parasitology. 21 (2): 193–204. doi:10.3347/kjp.1983.21.2.193. PMID 12902649.

- Urabe, M (2005). "Cercariae of a species of Philophthalmus detected in a freshwater snail, Semisulcospira libertina". Parasitology International. 54 (1): 55–57. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2004.10.002.

- Baba, T.; Hosoi, M.; Urabe, M.; Shimazu, T.; Tochimoto, T.; Hasegawa, H. (2011). "Liolope copulans (Trematoda: Digenea: Liolopidae) parasitic in Andrias japonicus (Amphibia: Caudata: Cryptobranchidae) in Japan: Life cycle and systematic position inferred from morphological and molecular evidence". Parasitology International. 60 (2): 181–192. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2011.02.002. PMID 21345377.

- Urabe, M (2001). "Life cycle of Genarchopsis goppo (Trematoda: Derogenidae) from Nara, Japan". Journal of Parasitology. 87 (6): 1404–1408. doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[1404:LCOGGT]2.0.CO;2. PMID 11780829.

- Besprozvannykh, V. V.; Ngo, H.; Ha, N.; Hung, N.; Rozhkovan, K.; Ermolenko, A. (2013). "Descriptions of digenean parasites from three snail species, Bithynia fuchsiana (Morelet), Parafossarulus striatulus Benson and Melanoides tuberculata Müller, in North Vietnam". Helminthologia. 50 (3): 190–204. doi:10.2478/s11687-013-0131-5.

- Shinagawa, K.; Urabe, M.; Nagoshi, M. (2001). "Effects of trematode infection on metabolism and activity in a freshwater snail, Semisulcospira libertina". Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 45 (2): 141–144. doi:10.3354/dao045141. PMID 11463101.

- Chae, J.-S.; Kim, E.-H.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, M.-J.; Cho, Y.-H.; Park, B.-K. (2003). "Prevalence and Sequence Analyses of Neorickettsia risticii". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 990 (1): 248–256. Bibcode:2003NYASA.990..248C. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07372.x. PMID 12860635.

- Hsu, K.-C.; Bor, H.; Lin, H.-D.; Kuo, P.-H.; Tan, M.-S.; Chiu, Y.-W. (2014). "Mitochondrial DNA phylogeography of Semisulcospira libertina (Gastropoda: Cerithioidea: Pleuroceridae): implications the history of landform changes in Taiwan". Molecular Biology Reports. 41 (6): 3733–3743. doi:10.1007/s11033-014-3238-y. PMID 24584517. S2CID 1460826.

- Moriya, S.; Yamauchi, T.; Nakagoshi, N. (2010). "Sex ratios in the Japanese firefly, Luciola cruciata (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) at emergence". Japanese Journal of Limnology (in Japanese). 69 (3): 255–258. doi:10.3739/rikusui.69.255.

- Kim, H.; Song, M.-J.; Heldenbrand, B.; Choi, K. (2014). "A Comparative Analysis of Ethnomedicinal Practices for Treating Gastrointestinal Disorders Used by Communities Living in Three National Parks (Korea)". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014: 108037, Table 3. doi:10.1155/2014/108037. PMID 25202330.

- Kim, H.; Song, M.-J. (2013). "Ethnomedicinal Practices for Treating Liver Disorders of Local Communities in the Southern Regions of Korea". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013: 869176. doi:10.1155/2013/869176.

Further reading

- Chang, Y. J.; Chang, H. J.; Min, B. H.; Bang, I. C. (2000). "Reproductive cycle of the melania snail, Semisulcospira libertina libertina". Development and Reproduction (in Korean). 4 (2): 175–180.

- Itagaki, H (1960). "Anatomy of Semisulcospira bensoni, a fresh-water gastropod". Venus. 21 (1): 41–50.

- Jarilla, B. R.; Uda, K.; Suzuki, T.; Acosta, L. P.; Urabe, M.; Agatsuma, T. (2014). "Characterization of arginine kinase from the caenogastropod Semisulcospira libertina, an intermediate host of Paragonimus westermani". Journal of Molluscan Studies. 80 (4): 444–451. doi:10.1093/mollus/eyu053.

- Kajiyama, H.; Habe, T. (1961). "Two new forms of the Japanese melanians; Semisulcospira". Venus. 21 (2): 167–176.

- Kamiya, S.; Shimamoto, M. (2005). "Genetic and morphological variations of two freshwater snails, Semisulcospira libertina and S. reiniana in Japan". Venus (in Japanese). 64: 161–176.

- Kim, E. K.; Lee, J. S. (2009). "다슬기, Semisulcospira libertina libertina의 난자형성과정에 관한 미세구조적 기재. Ultrastructural Description on Oogenesis of the Melania Snail, Semisulcospira libertina libertina (Gastropoda: Pleuroceridae)". The Korean Journal of Malacology (in Korean). 25 (2): 145–151.

- Kim; Lee, T.-K.; Cha, Y.-S. (1985). "Studies on the nutritive component of black snail (Semisulcospira libertina)". Bull. Agric. College, Chonbuk Univ. 16: 101–105.

- Kim, Y.-K.; Moon, H.-S.; Lee, M.-H.; Park, M.-J.; Lim, C.-W.; Park, H.-Y.; Park, J.-I.; Yoon, H.-D.; Kim, D.-H. (2009). "Biological activities of seven melania snails in Korea" (PDF). Korean Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 42 (5): 434–441. doi:10.5657/kfas.2009.42.5.434.

- Kimura, M.; Oniwa, K. (1984). "Protein polymorphism in the fresh water snail Semisulcospira libertina". Animal Blood Groups and Biochemical Genetics. 15 (1): 71–76. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2052.1984.tb01100.x. PMID 6742518.

- Kimura, D.; Uga, S. (2003). "Epidemiological studies on Centrocestus spp (Trematoda: Heterophyidae) in Chikusa river basin, Hyogo Prefecture Japan: Infection in first intermediate host snail, Semisulcospira libertina". Japan Journal of Environmental Entomology and Zoology. 14: 97–103.

- (in German) Kobelt W. (1879). "Fauna molluscorum extramarinorum Japoniae. Nach den von professor Rein gemachten sammlungen". Abhandlungen d. Senckenberg. naturf. gesellsch 1–171, 23 plates. page 128-130, plate xviii, figs. 2–8; plate xix, figs. 2–5, 8.

- Mishima Y. (1973). "Production estimation of a freshwater snail, Semisulcospira bensoni (Philippi) (Mollusca: Gastropoda) in a rapid stream". Report from the Ebino Biological Laboratory, Kyushu University, 1: 49-63.

- Mori, S (1936). "Some ecological notes on the fresh water snails, Melanoides (Semisulcospira) libertinus (Gould), M. (S.) japonicus (Reeve), and M. (S.) niponicus (Smith)". Venus (in Japanese). 6: 14–21.

- Nishiwaki, S.; Koike, K. (2000). "カワニナの模式産地の検討 The Type Locality of Semisulcospira libertina (Gould, 1859)". Venus (in Japanese). 31 (3): 61–62.

- Okura, N.; Kurihara, K.; Yasuzumi, F. (2005). "Striated microfilament bundles attaching to the plasma membrane of cytoplasmic bridges connecting spermatogenic cells in the black snail, Semisulcospira libertina (Mollusca, Mesogastropoda)". Tissue and Cell. 37 (1): 75–79. doi:10.1016/j.tice.2004.10.001. PMID 15695179.

- Rossetti, Y.; Nagasaka, T. (1988). "Prostaglandin E1, prostaglandin E2, and endotoxin failure to produce fever in the Japanese freshwater snail Semisulcospira libertina". The Japanese Journal of Physiology. 38 (2): 179–186. doi:10.2170/jjphysiol.38.179. PMID 3172578.

- Shinagawa, K.; Urabe, M.; Nagoshi, M. (1999). "Relationships between trematode infection and habitat depth in a freshwater snail, Semisulcospira libertina (Gould)". Hydrobiologia. 397: 171–178. doi:10.1023/A:1003680127338. S2CID 27808443.

- Tang, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, Z. (2012). "A Primary Study for Semisulcospira libertina Decollation". Sichuan Journal of Zoology. 31 (6): 896–899.

- Xue, J.; Wu, H.; Song, L. (2003). "Spatial pattern of Semisulcospira libertina population in small watershed in western Zhejiang" (PDF). Chinese Journal of Applied and Environmental Biology (in Chinese). 9 (2): 175–178.

- Yamamoto, K.; Handa, T. (2009). ""カワニナの中腸腺の導管と中腸腺細管の構造. Structure of Duct and Tubule of Digestive Diverticula in the Snail,Semisulcospira libertina (Gastropoda : Mesogastropoda")" (PDF). Journal of National Fisheries University (in Japanese). 57 (4): 271–275.

- Yasuzumi, G.; Nakano, S.; Matsuzaki, W. (1962). "Elektronenmikroskopische untersuchungen über die spermatogenese. XI. Über die spermiogenese der atypischen spermatiden von Melania libertina Gould". Zeitschrift für Zellforschung (in German). 57: 495–511. doi:10.1007/bf00339879.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Semisulcospira libertina. |

- (in Japanese) Semisulcospira libertina with extensive gallery