Maxima and minima

In mathematical analysis, the maxima and minima (the respective plurals of maximum and minimum) of a function, known collectively as extrema (the plural of extremum), are the largest and smallest value of the function, either within a given range (the local or relative extrema) or on the entire domain (the global or absolute extrema).[1][2][3] Pierre de Fermat was one of the first mathematicians to propose a general technique, adequality, for finding the maxima and minima of functions.

As defined in set theory, the maximum and minimum of a set are the greatest and least elements in the set, respectively. Unbounded infinite sets, such as the set of real numbers, have no minimum or maximum.

Definition

A real-valued function f defined on a domain X has a global (or absolute) maximum point at x∗ if f(x∗) ≥ f(x) for all x in X. Similarly, the function has a global (or absolute) minimum point at x∗ if f(x∗) ≤ f(x) for all x in X. The value of the function at a maximum point is called the maximum value of the function and the value of the function at a minimum point is called the minimum value of the function. Symbolically, this can be written as follows:

- is a global maximum point of function if

Similarly for global minimum point.

If the domain X is a metric space then f is said to have a local (or relative) maximum point at the point x∗ if there exists some ε > 0 such that f(x∗) ≥ f(x) for all x in X within distance ε of x∗. Similarly, the function has a local minimum point at x∗ if f(x∗) ≤ f(x) for all x in X within distance ε of x∗. A similar definition can be used when X is a topological space, since the definition just given can be rephrased in terms of neighbourhoods. Mathematically, the given definition is written as follows:

- Let be a metric space and function . Then is a local maximum point of function if such that

Similarly for a local minimum point.

In both the global and local cases, the concept of a strict extremum can be defined. For example, x∗ is a strict global maximum point if, for all x in X with x ≠ x∗, we have f(x∗) > f(x), and x∗ is a strict local maximum point if there exists some ε > 0 such that, for all x in X within distance ε of x∗ with x ≠ x∗, we have f(x∗) > f(x). Note that a point is a strict global maximum point if and only if it is the unique global maximum point, and similarly for minimum points.

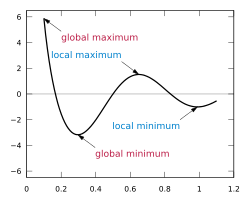

A continuous real-valued function with a compact domain always has a maximum point and a minimum point. An important example is a function whose domain is a closed (and bounded) interval of real numbers (see the graph above).

Search

Finding global maxima and minima is the goal of mathematical optimization. If a function is continuous on a closed interval, then by the extreme value theorem global maxima and minima exist. Furthermore, a global maximum (or minimum) either must be a local maximum (or minimum) in the interior of the domain, or must lie on the boundary of the domain. So a method of finding a global maximum (or minimum) is to look at all the local maxima (or minima) in the interior, and also look at the maxima (or minima) of the points on the boundary, and take the largest (or smallest) one.

Likely the most important, yet quite obvious, feature of continuous real-valued functions of a real variable is that they decrease before local minima and increase afterwards, likewise for maxima. (Formally, if f is continuous real-valued function of a real variable x then x0 is a local minimum iff there exist a<x0<b such that f decreases on (a,x0) and increases on (x0,b))[4] A direct consequence of this is the Fermat's theorem, which states that local extrema must occur at critical points. One can distinguish whether a critical point is a local maximum or local minimum by using the first derivative test, second derivative test, or higher-order derivative test, given sufficient differentiability.

For any function that is defined piecewise, one finds a maximum (or minimum) by finding the maximum (or minimum) of each piece separately, and then seeing which one is largest (or smallest).

Examples

- The function x2 has a unique global minimum at x = 0.

- The function x3 has no global minima or maxima. Although the first derivative (3x2) is 0 at x = 0, this is an inflection point.

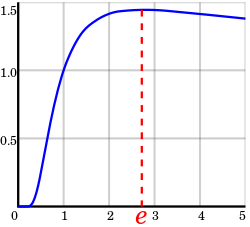

- The function has a unique global maximum at x = e. (See figure at right)

- The function x−x has a unique global maximum over the positive real numbers at x = 1/e.

- The function x3/3 − x has first derivative x2 − 1 and second derivative 2x. Setting the first derivative to 0 and solving for x gives stationary points at −1 and +1. From the sign of the second derivative we can see that −1 is a local maximum and +1 is a local minimum. Note that this function has no global maximum or minimum.

- The function |x| has a global minimum at x = 0 that cannot be found by taking derivatives, because the derivative does not exist at x = 0.

- The function cos(x) has infinitely many global maxima at 0, ±2π, ±4π, ..., and infinitely many global minima at ±π, ±3π, ±5π, ....

- The function 2 cos(x) − x has infinitely many local maxima and minima, but no global maximum or minimum.

- The function cos(3πx)/x with 0.1 ≤ x ≤ 1.1 has a global maximum at x = 0.1 (a boundary), a global minimum near x = 0.3, a local maximum near x = 0.6, and a local minimum near x = 1.0. (See figure at top of page.)

- The function x3 + 3x2 − 2x + 1 defined over the closed interval (segment) [−4,2] has a local maximum at x = −1−√15/3, a local minimum at x = −1+√15/3, a global maximum at x = 2 and a global minimum at x = −4.

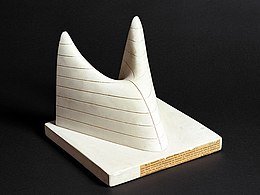

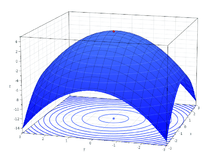

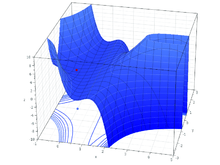

Functions of more than one variable

For functions of more than one variable, similar conditions apply. For example, in the (enlargeable) figure at the right, the necessary conditions for a local maximum are similar to those of a function with only one variable. The first partial derivatives as to z (the variable to be maximized) are zero at the maximum (the glowing dot on top in the figure). The second partial derivatives are negative. These are only necessary, not sufficient, conditions for a local maximum because of the possibility of a saddle point. For use of these conditions to solve for a maximum, the function z must also be differentiable throughout. The second partial derivative test can help classify the point as a relative maximum or relative minimum. In contrast, there are substantial differences between functions of one variable and functions of more than one variable in the identification of global extrema. For example, if a bounded differentiable function f defined on a closed interval in the real line has a single critical point, which is a local minimum, then it is also a global minimum (use the intermediate value theorem and Rolle's theorem to prove this by reductio ad absurdum). In two and more dimensions, this argument fails, as the function

shows. Its only critical point is at (0,0), which is a local minimum with ƒ(0,0) = 0. However, it cannot be a global one, because ƒ(2,3) = −5.

Maxima or minima of a functional

If the domain of a function for which an extremum is to be found consists itself of functions, i.e. if an extremum is to be found of a functional, the extremum is found using the calculus of variations.

In relation to sets

Maxima and minima can also be defined for sets. In general, if an ordered set S has a greatest element m, m is a maximal element. Furthermore, if S is a subset of an ordered set T and m is the greatest element of S with respect to order induced by T, m is a least upper bound of S in T. The similar result holds for least element, minimal element and greatest lower bound. The maximum and minimum function for sets are used in databases, and can be computed rapidly, since the maximum (or minimum) of a set can be computed from the maxima of a partition; formally, they are self-decomposable aggregation functions.

In the case of a general partial order, the least element (smaller than all other) should not be confused with a minimal element (nothing is smaller). Likewise, a greatest element of a partially ordered set (poset) is an upper bound of the set which is contained within the set, whereas a maximal element m of a poset A is an element of A such that if m ≤ b (for any b in A) then m = b. Any least element or greatest element of a poset is unique, but a poset can have several minimal or maximal elements. If a poset has more than one maximal element, then these elements will not be mutually comparable.

In a totally ordered set, or chain, all elements are mutually comparable, so such a set can have at most one minimal element and at most one maximal element. Then, due to mutual comparability, the minimal element will also be the least element and the maximal element will also be the greatest element. Thus in a totally ordered set we can simply use the terms minimum and maximum. If a chain is finite then it will always have a maximum and a minimum. If a chain is infinite then it need not have a maximum or a minimum. For example, the set of natural numbers has no maximum, though it has a minimum. If an infinite chain S is bounded, then the closure Cl(S) of the set occasionally has a minimum and a maximum, in such case they are called the greatest lower bound and the least upper bound of the set S, respectively.

See also

References

- Stewart, James (2008). Calculus: Early Transcendentals (6th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-495-01166-8.

- Larson, Ron; Edwards, Bruce H. (2009). Calculus (9th ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-547-16702-2.

- Thomas, George B.; Weir, Maurice D.; Hass, Joel (2010). Thomas' Calculus: Early Transcendentals (12th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-58876-0.

- Problems in mathematical analysis. Demidovǐc, Boris P., Baranenkov, G. Moscow(IS): Moskva. 1964. ISBN 0846407612. OCLC 799468131.CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Extrema (calculus). |

| Look up maxima, minima, or extremum in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Maxima and Minima From MathWorld—A Wolfram Web Resource.

- Thomas Simpson's work on Maxima and Minima at Convergence

- Application of Maxima and Minima with sub pages of solved problems