Scotiabank

The Bank of Nova Scotia (French: La Banque de Nouvelle-Écosse), operating as Scotiabank (French: Banque Scotia), is a Canadian multinational banking and financial services company. One of Canada's Big Five banks, it is the third largest Canadian bank by deposits and market capitalization. It serves more than 25 million customers around the world and offers a range of products and services including personal and commercial banking, wealth management, corporate and investment banking. With more than 88,000 employees and assets of $998 billion (as of October 31, 2018), Scotiabank trades on the Toronto (TSX: BNS) and New York Exchanges (NYSE: BNS).

| Scotiabank | |

| Public | |

| Traded as | TSX: BNS NYSE: BNS TTSE: SBTT S&P/TSX 60 component |

| ISIN | CA0641491075 |

| Industry | Banking, Financial services |

| Founded | 30 March 1832 Halifax, Nova Scotia |

| Headquarters | Toronto, Ontario, Canada[1] |

Key people | Brian J. Porter (President and CEO) Raj Viswanathan (CFO) |

| Revenue | |

| AUM | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 60,000 (2017)[2] |

| Subsidiaries | Tangerine Bank |

| Website | www |

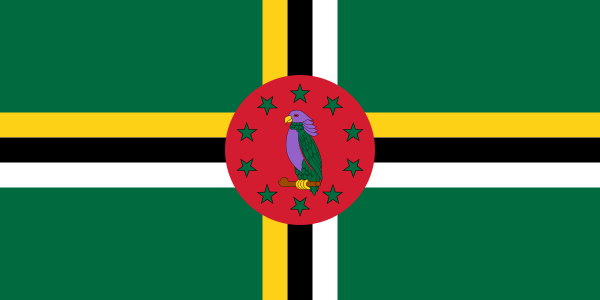

Founded in 1832 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Scotiabank moved its executive offices to Toronto, Ontario in 1900.[3] Scotiabank has billed itself as "Canada's most international bank" due to its acquisitions primarily in Latin America and the Caribbean, and also in Europe and parts of Asia. Scotiabank is a member of the London Bullion Market Association and one of fifteen accredited institutions which participate in the London gold fixing.[4] From 1997 to 2019, this was conducted through its precious metals division ScotiaMocatta.[5]

Scotiabank is led by President and CEO Brian J. Porter.[6]

History

19th century

The bank was incorporated by the Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia on March 30, 1832, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, with William Lawson serving as the first president.[7] Scotiabank was founded in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1832 under the name of The Bank of Nova Scotia. The bank intended to facilitate the trans-Atlantic trade of the time.[3] Later, in 1883, The Bank of Nova Scotia acquired the Union Bank of Prince Edward Island, although most of the bank's expansion efforts in the century took the form of branch openings.[8]

The bank launched its branch banking system by opening in Windsor, Nova Scotia. The expansion was limited to the Maritimes until 1882, when the bank moved west by opening a branch in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The Manitoba branch later closed, but the bank continued to expand into the American Midwest. This included opening a branch in Minneapolis in 1885, which later transferred to Chicago in 1892. Following the collapse of the Commercial Bank of Newfoundland and Union Bank of Newfoundland on December 10, 1894, The Bank of Nova Scotia established on December 15, 1894, in Newfoundland.[7]

The bank opened a branch in Kingston, Jamaica in 1889 to facilitate the trading of sugar, rum, and fish. This was Scotiabank's first move into the Caribbean and historically the first branch of a Canadian bank to open outside of the United States or the United Kingdom.[3][8] In 1899, Scotiabank opened a branch in Boston, Massachusetts. By the end of the 19th century, the bank was represented in all of the Maritimes, Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba. In 1900, the bank moved its headquarters to Toronto, Ontario.[9][8]

20th century

The bank continued to grow with the opening of new branches in the early 20th century. In 1906, the Bank of Nova Scotia opened a branch in Havana, Cuba, followed by a branch in New York City in the following year. In 1910, the bank opened a branch in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The bank also grew with the merger and acquisition of other banks, including the Bank of New Brunswick in 1913, and the Toronto-based Metropolitan Bank in 1914.[8] The acquisition of Metropolitan Bank made the Bank of Nova Scotia the fourth largest financial institution in Canada at that time.[8] In 1919, the bank amalgamated with the Bank of Ottawa.[8]

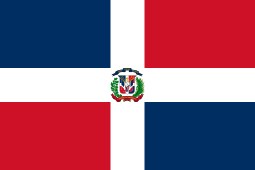

In 1919, the bank opened a branch in Fajardo, Puerto Rico. In the following year, the bank opened a branch in London, and another in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. The bank also saw growth in Cuba, with five branches in Havana, and one branch each in Camagüey, Cienfuegos, Manzanillo, and Santiago de Cuba by 1931.

During the mid 20th century, the bank grew not only in size but also in breadth of products and services. Progress was conditioned by changing consumer needs, legal changes, or acquisitions of external service providers. Major changes include:[8] Following the passage of the National Housing Act, the Bank of Nova Scotia created a mortgage department in 1954. Further changes to the Bank Act of 1954 in 1958 led to the bank introducing its consumer credit program.

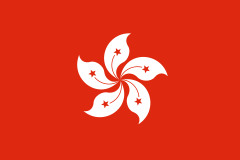

The bank's branches in Cuba continued to operate until 1960, when the Government of Cuba nationalized all banks in Cuba, and the Bank of Nova Scotia withdrew its services from all eight branches. The bank expanded into Asia with the opening of a Representative Office in Japan.[8] During the 1960s, the Bank of Nova Scotia became the first Canadian bank to appoint women as bank managers, with the first appointed on 11 September 1961.[7] In the next year, the bank expanded into Asia with the opening of a Representative Office in Japan.[8]

In 1975, the Bank of Nova Scotia adopted Scotiabank as its worldwide brand name. On 28 September 1978, Scotiabank and Canadian Union of Public Employees signed a collective agreement in Toronto, making Scotiabank the first Canadian bank to sign a collective agreement with a union.[7]

In 1986, Scotiabank created Scotia Securities to provide discount brokerage and security underwriting services. The late 1980s and 1990s saw the bank acquire several firms, including McLeod Young Weir Ltd brokerage firm in 1988, and Montreal Trustco Inc. in 1994. In 1997, the bank acquired National Trustco Inc. for C$1.25 billion. In the same year, Scotiabank acquired Banco Quilmes in Argentina.

21st century

In 2000, Scotiabank increased its stake in Mexican bank Grupo Financiero Inverlat to 55 percent. The Mexican bank was subsequently renamed to Grupo Financiero Scotiabank Inverlat.[8] Scotabank later acquired Inverlat banking house in 2003, taking over all of its branches and establishing a strong presence in the country.

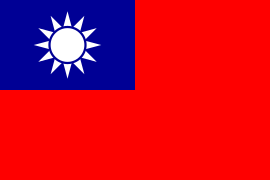

In 2002, Scotiabank shut its branches (formerly Banco Quilmes) in Argentina during the currency crisis and massive sovereign default. In the following year, Scotiabank's Guangzhou branch was awarded the first licence to a Canadian bank by the Chinese government to deal in Chinese currency.[7] In 2007, Scotiabank acquired a 24.98 per cent stake in Thanachart Bank, with that share later increasing to 48.99 per cent by December 2014. With the acquisition of Siam City Bank, Thanachart Bank is now the 6th largest bank (by assets) in Thailand with over 16,000 staff serving more than four million customers through 680 branches and 2,100 ATMs across the country.[10]

In 2010, the bank opened its first offices in Bogotá, Colombia. On October 20, 2011, Scotiabank acquired a 51% stake in Colpatria, Colombia's fifth largest bank and second largest issuer of credit cards, for $1 billion Canadian in cash and stock (10 million shares). It is the second largest foreign transaction ever by a Canadian financial company overseas, behind Royal Bank of Canada's purchase in Royal Bank of Trinidad and Tobago.[11]

In 2012, Scotiabank entered into an agreement to acquire ING Direct Bank of Canada from ING Groep N.V. Two years later, Scotiabank would acquire ING Direct Bank of Canada for C$3.13 billion.[12] The sale completed on 15 November 2012,[13] and ING Bank of Canada was later renamed it Tangerine in April 2014.

As a result of the FATCA agreement between Canada and the United States, signed between the two countries in 2014, Scotiabank has also spent almost $100 million implementing a controversial system to report to the United States the account holdings of close to one million Canadians of American origin and their Canadian-born spouses. Scotiabank has been forced to implement this system in order to comply with FATCA. According to Financial Post, FATCA requires Canadian banks to provide information to the United States including total assets, account balances, account numbers, transactions, account numbers, and other personal identifying information, as well as assets held jointly with Canadian-born spouses and other family members.[14][15]

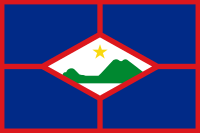

On 14 July 2015, Scotiabank announced that it would buy Citigroup's retail and commercial banking operations in Panama and Costa Rica. Terms of the transaction were not disclosed. The purchase would increase Scotiabank's client base in both countries from 137,000 to 387,000, and would add 27 branches to the existing 51 branches in both Central American nations.[16]

Scotiabank's former President, CEO and Chairman Cedric Ritchie died on March 20, 2016. He was a President of Scotiabank from 1972, and CEO and Chairman from 1974 to 1995. Under his leadership, Scotiabank expanded into more than 40 countries and grew to 33,000 employees.[17]

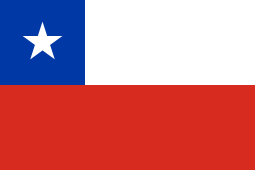

In 2018, Scotiabank acquired Montreal investment firm Jarislowsky Fraser, also in 2018 Scotiabank completed the acquisition of a 68.19% stake in BBVA Chile for C$ 2.9 billion, as a result BBVA Chile was merged into Scotiabank Chile[18]. On 21 February 2019, the Prosecutor in the Central American country of Costa Rica raided Scotiabank's offices in San José, Costa Rica, claiming that the bank had failed to provide the government with information on accounts and deposits that could allegedly implicate Alejandro Toledo, the former president of Peru, in money laundering.[19] Later that year, in June 2019 it was announced that OFG Bancorp would acquire all branches of Scotiabank within Puerto Rico and The United States Virgin Islands territories as part of a $550M cash deal.

In 2019, Scotiabank underwent a rebranding, modifying its wordmark logo and introducing a new corporate font based on its design, downplaying the company's S and globe monogram, and increasing use of the abbreviated name "Scotia".[20]

Acquisitions and mergers

The bank has amalgamated with several other Canadian financial institutions through the years and purchased several other banks overseas.[3][21] Most have been rebranded since their acquisition, although a few continue to utilize their former names. Several branches of the former Montreal Trust and National Trust were rebranded Scotiabank & Trust, and continue to operate as such.

.jpg)

.jpg)

| Bank | Year established | Year of amalgamation |

|---|---|---|

Operating units

Scotiabank has four business lines:[22]

- Canadian Banking provides financial advice and banking to personal and business customers across Canada. Scotiabank also provides an alternative self-directed banking method through Tangerine Bank.

- International Banking provides financial products and advice to retail and commercial customers in select regions outside of Canada, supplemented by additional products and services offered by Global Banking & Markets and Global Wealth & Insurance.

- Global Wealth & Insurance (GWI) combines the Bank's wealth management and insurance operations in Canada and internationally, and Global Transaction Banking. GWI is diversified across geographies and product lines.

- Global Banking & Markets, Scotiabank's wholesale banking and capital markets arm, offers various products and services to corporate, government and institutional investor clients globally.

| Year | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenues, bln $ | 10.365 | 10.727 | 10.261 | 10.295 | 10.726 | 11.208 | 12.490 | 11.876 | 14.457 | 15.505 | 17.310 | 19.646 | 21.299 | 23.604 | 24.049 | 26.350 | 27.155 | 28.775 |

| Net income, bln $ | 2.077 | 1.708 | 2.422 | 2.908 | 3.209 | 3.579 | 4.045 | 3.140 | 3.547 | 4.239 | 5.330 | 6.390 | 6.610 | 7.298 | 7.213 | 7.368 | 8.243 | 8.724 |

| Assets, bln $ | 284.4 | 296.4 | 285.9 | 279.2 | 314.0 | 379.0 | 411.5 | 507.6 | 496.5 | 526.7 | 594.4 | 668.2 | 743.6 | 805.7 | 856.5 | 896.3 | 915.3 | 998.5 |

| Employees | 46,804 | 44,633 | 43,986 | 43,928 | 46,631 | 54,199 | 58,113 | 69,049 | 67,802 | 70,772 | 75,362 | 81,497 | 86,690 | 86,932 | 89,214 | 88,901 | 88,645 | 97,629 |

| Branches | 2005 | 1847 | 1850 | 1871 | 1959 | 2191 | 2331 | 2672 | 2686 | 2784 | 2926 | 3123 | 3330 | 3288 | 3177 | 3113 | 3003 | 3,095 |

| Agency | Rating | |

|---|---|---|

| DBRS | AA | Stable |

| Fitch | AA- | Stable |

| Moody's | Aa2 | Stable |

| Standard & Poor's | A+ | Stable |

Branch and office locations

Canadian

Scotiabank operates branches in all Canadian provinces and territories, except for Nunavut.

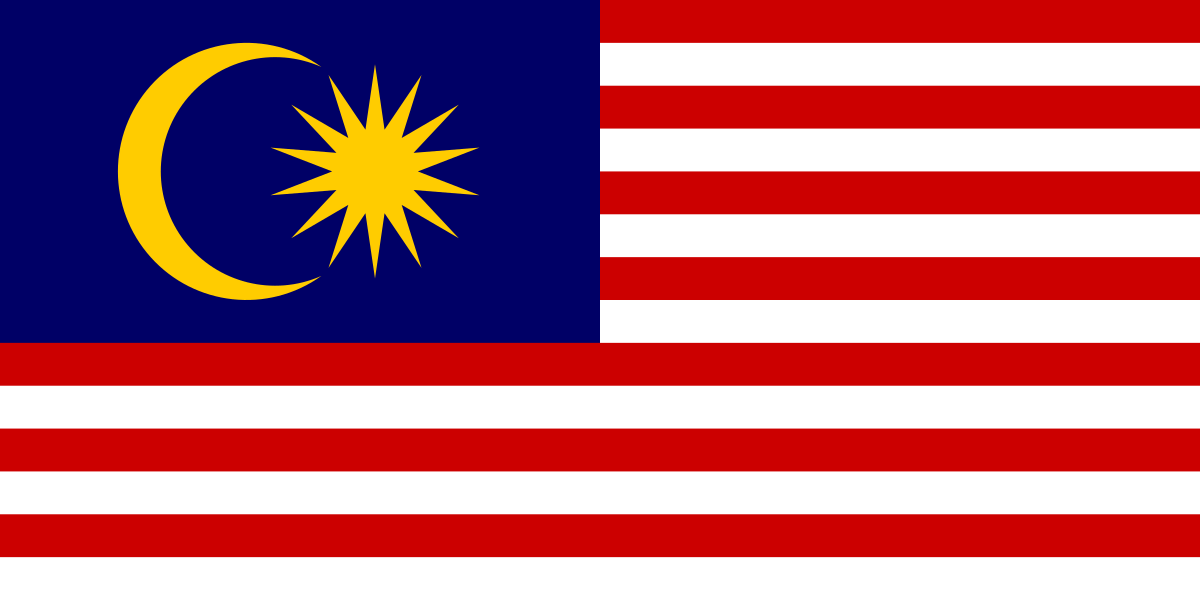

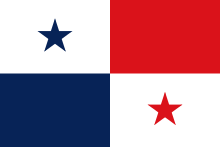

Global

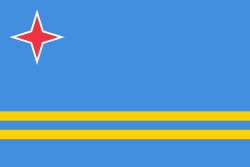

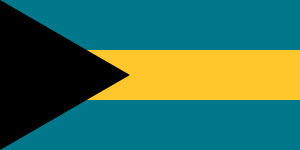

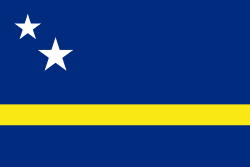

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Sponsorship

Sports

Scotiabank is the title sponsor for a number of sports events including the Calgary Marathon, the CONCACAF Champions League tournament (since 2015), and the Jewish National Fund's "Pitch for Israel" event. Scotiabank is also the title sponsor for running events that form a part of the Canada Running Series. They include Banque Scotia 21k de Montreal + 10k & 5k in April; Scotiabank Vancouver Half-Marathon & 5k Run/Walk in June; Scotiabank Toronto Waterfront Marathon, Half-Marathon & 5k in October; and the Scotiabank Bluenose Marathon.[24] Since 2005, Scotiabank has also been the title sponsor of the CFL playoffs semi-final and conference final games, with games titled as the Scotiabank East Semi-finals and Scotiabank West Semi-finals. This is in addition to being the official financial services provider to the Canadian Football League. Scotiabank was also a primary sponsor for Champion Boxer Miguel Cotto during his 2009 bout with Manny Pacquiao.

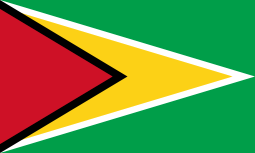

Other sporting events Scotiabank has sponsored includes the 2007 Cricket World Cup, during which it was awarded the title as the official bank of the tournament by the International Cricket Council. During the event, several stadia and venues across the Caribbean (and Guyana in South America) are to become outfitted with Scotiabank automated banking machines.[25] In 2010, Scotiabank was a sponsor of the World Rally Championship's Corona Rally Mexico. Since 2008, Scotiabank has been the official team sponsor of Canadian Cricket Team and the title sponsor of National T20 Championship in Canada.

Scotiabank also sponsors sports leagues and teams, becoming a sponsor for Club Deportivo Guadalajara in 2013; and becoming the official sponsor for the Chilean Primera División after signing a five-year period contract in 2014. Scotiabank is also the official bank of the National Hockey League and National Hockey League Players' Association.[26] Scotiabank also sponsors the Little NHL (native hockey league) and several girls' hockey festivals across Canada. In October 2007, Scotiabank became a sponsor of the Hockey Night in Canada broadcast by Canadian Broadcasting Corporation/Sportsnet and the title sponsor for its pregame show, Scotiabank Hockey Tonight. Other sports broadcasts sponsored by Scotiabank includes CTV Television Network's and TSN's coverage of Premier League Soccer and the FA Cup Final, since 2013.

_(21066808744).jpg)

In addition to sporting broadcasts and events, Scotiabank is also the title sponsor for a number of athletic facilities. They include the Scotiabank Aquatics Center in Guadalajara; Scotiabank Saddledome in Calgary (since 8 October 2010); and the Scotiabank Centre in Halifax (since 25 June 2014). The naming rights for the Scotiabank Centre was signed for ten years, with annual fees of $650,000 for said rights.[27] The facility official opened its doors as the rebranded Scotiabank Centre on September 19, 2014.[28] On 29 August 2017, Scotiabank and Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment, announced that Scotiabank purchased the naming rights to the Air Canada Centre for $800 million. The multi-sport complex was renamed 1 July 2018 as Scotiabank Arena.[29] From 2006 through 2013, Scotiabank held the naming rights to the arena of the Ottawa Senators, branding it Scotiabank Place. Canadian Tire took over the naming rights for the Senators' arena in June 2013.[30]

Culture

Scotiabank has been a title sponsor for a number of cultural events and institutions in Canada. In 2005, Scotiabank became title sponsor of the Giller Prize.[31] From 2006 to 2015, Scotiabank was the title sponsor for the Nuit Blanche event in Toronto.[32] In 2008, Scotiabank announced a two-year sponsorship of Toronto's Caribana which would be rebranded as Scotiabank Caribbean Carnival Toronto. The sponsorship of the Caribbean festival was extended until 2015, when the partnership with the festival ended.[32] In 2016 Scotiabank held its first hackathon with the goal of solving Canadian debt.

Scotiabank and Canadian theatre operator, Cineplex Entertainment, partnered together in 2007 to create a loyalty rewards program called Scene. The program allows patrons to sign-up for a special card that grants them points which can be redeemed for free movies or concession discounts. Scotiabank customers can also request a Scene debit card which gives them points when used. The bank launched a Scene Visa credit card in early May. Five Cineplex Entertainment locations were also rebranded as "Scotiabank Theatres." In 2015, the two companies announced they extended the partnership through 31 October 2025 and would expand naming rebrand another five theatres as Scotiabank Theatres.[33]

Scotiabank is also the title sponsor for two post-secondary facilities in Canada, including Scotiabank Hall at Brock University in St. Catharines;[34] and Scotiabank Hall in the Marion McCain Arts and Social Sciences Building at Dalhousie University in Halifax.[35] Scotiabank has also established an industry partnership with the University of Waterloo Stratford Campus.[36]

Awards

- 2005 – "Bank of the Year" – For Mexico, the Caribbean and in Jamaica by LatinFinance.[37]

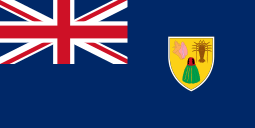

- 2007 – "Bank of the Year" The Banker – London England, Scotiabank Trinidad and Tobago, Scotiabank Belize, Scotiabank Turks and Caicos

- 2008 – "Bank of the Year" The Banker - London England, Scotiabank Barbados, Scotiabank Trinidad and Tobago, Scotiabank Guyana, Scotiabank Turks and Caicos

- 2009 – "Bank of the Year" The Banker – London England, Scotiabank Canada, Scotiabank Barbados, Scotiabank Dominican Republic, Scotiabank Trinidad and Tobago, Scotiabank Turks and Caicos

- 2010 – "Bank of the Year" The Banker – London England, Scotiabank Barbados, Scotiabank Trinidad and Tobago, Scotiabank Turks and Caicos

- 2011 – "Best Emerging Market Bank" Global Finance Magazine – New York, Scotiabank Jamaica, Scotiabank Barbados, Scotiabank Costa Rica, Scotiabank Turks and Caicos.[38]

- 2012 - "Global Bank of the Year" The Banker "Bank of the Year" for the Americas, Antigua, Barbados, Belize, British Virgin Islands, Canada and Turks and Caicos.[39]

- 2013 - "Bank of the Year" in British Virgin Islands, Canada, Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago by The Banker.[40]

- 2014 – "Best Emerging Market Bank in Latin America" Global Finance Magazine in Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad & Tobago, Turks and Caicos and U.S. Virgin Islands.[41]

Controversies

Fraud in Mexico

A 2001 investigation into the murder of Maru Oropesa, a Scotiabank branch manager in Mexico City revealed US$14 million missing from the branch. Initially, investigators found that Oropesa and Jaime Ross, her former boss, had illegally transferred US$5 million from client investment accounts. The money was eventually transferred to the United States where it was used to purchase three aircraft. As the investigation continued, officials found an additional $9 million missing and involvement of 16 other bank employees in the fraud.[42][43] Ross was convicted of fraud and money laundering for his role and sentenced to 15 years.[44] Scotiabank terminated the other 16 employees, but did not prosecute them.[42]

Unpaid overtime lawsuit

In 2014, the bank reached a settlement in a class-action lawsuit that covered thousands of workers owed more than a decade of unpaid overtime. The lawsuit included 16,000 Scotiabank employees across Canada who worked as personal banking officers, senior personal banking officers, financial advisors, and small business account managers from January 1, 2000, to December 1, 2013. The 2007 lawsuit was similar to a class-action filed by Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC) bank teller Dara Fresco of Toronto.

Under terms of the settlement, employees received 1.5 times their standard wage at the time, but no interest. Scotiabank also paid legal fees of $10.45 million.[45][46]

Wrongful dismissal lawsuit

In June 2005, David Berry, a very successful Canadian Scotiabank trader who had built a $75M/year business in trading preferred shares, was fired on the grounds that he had committed securities regulatory violations.[47] At the time, as part of a 20 per cent direct drive deal, he was making more than double the CEO's salary and Scotiabank management had already taken steps to limit his compensation.[48] The regulatory violation allegations from his former employer, left him unemployable to Scotiabank's competitors despite the appeal of potentially adding more than $75M/year to their equity trading profits.[48]

Documents delivered to the media showing that Scotiabank management had sought advice on terminating Berry prior to the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC) violation accusation, and the results of questioning during the IIROC inquiries strongly suggest that the securities charges were part of a plan by Scotiabank senior management to remove Berry from his position and simultaneously prevent him from becoming their competitor.[49]

In a ruling on January 15, 2013, more than seven years after the initial accusation, a hearing panel of the IIROC dismissed all charges against Berry.[50][51]

David Berry filed a $100M wrongful dismissal lawsuit against Scotiabank. As of January 2015, and nine years after Berry was terminated, Scotiabank settled with Berry for an undisclosed amount. Barry Critchley, who followed the story since its beginning, wrote an article on November 6, 2014, in which he believes Scotiabank's $55 million reported legal charges would likely be connected to the $100 million lawsuit; but it is unlikely to ever be known.[52]

Membership

Scotiabank is a member of the Canadian Bankers Association (CBA) and registered member with the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation (CDIC), a federal agency insuring deposits at all of Canada's chartered banks. It is also a member of the Global ATM Alliance, a joint venture of several major international banks that allows customers of the banks to use their ATM cards or check cards at certain other banks within the Global ATM Alliance without fees when traveling internationally. Other participating banks are Barclays (United Kingdom), Bank of America (United States), BNP Paribas (France and Ukraine through UkrSibbank), Deutsche Bank (Germany), and Westpac (Australia and New Zealand).[53] Other international associations the bank is a member of includes:

- Amex in Canadian markets

- CarIFS ATM Network

- Global ATM Alliance

- Interac

- MAGNA Rewards as part of the Scotiabank MAGNA MasterCard.

- MasterCard in the Caribbean markets

- MultiLink Network ATM network[54]

- NYCE ATM Network

- Plus Network for VISA card users

- VISA International

See also

References

- "Mail Us". Scotiabank. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- "2018 Annual Report" (PDF).

- "The Scotiabank Story". Scotiabank. 2010. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- "The London Gold Fix". Bullionvault Ltd. 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2016.

- "Scotiabank Drops 348-Year-Old Mocatta Name in Metals Unit Revamp". Bloomberg. 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- Touryalai, Halah (February 12, 2014). "Largest 100 banks in the world". Forbes. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Pound, Richard W. (2005). Fitzhenry and Whiteside Book of Canadian Facts and Dates. Fitzhenry and Whiteside. ISBN 978-1554550098.

- "The Bank of Nova Scotia History". Funding Universe. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Scotiabank". Toronto Star. May 3, 1904. p. 12. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Bank's Profile". Thanachart Bank. Retrieved January 1, 2016.

- Pasternak, Sean (October 20, 2011). "Scotiabank Buys Colpatria in Biggest International Purchase". Bloomberg Markets. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- "Scotiabank to buy ING Bank of Canada for $3.13 billion in cash". CTV News Channel. The Canadian Press. August 29, 2012.

- "ING completes sale of ING Direct Canada". Reuters. November 15, 2012. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

- Greenwood, John (October 23, 2013). "Electronic spying 'a big issue' for banks, Scotia CEO Waugh says". Financial Post.

- Swanson, Lynne. "Dual Canadian-American citizens: We are not tax cheats". Financial Post. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Scotiabank expands in Central America" (Press release). Scotiabank. July 14, 2015.

- Kiladze, Tim (March 21, 2016). "Former Bank of Nova Scotia head Cedric Ritchie dies at 88". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Scotiabank completes acquisition of majority stake in BBVA Chile". NS Banking. July 9, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- "Allanan Scotiabank por caso de Alejandro Toledo". Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- "No Love for the Globe". Brand New. UnderConsideration. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- Sawyer, Deborah C. (November 16, 2016). "Bank of Nova Scotia". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Corporate Profile". Scotiabank. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- "Annual Reports". Scotiabank.

- "Races". Canada Running Series. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Article 46(2) of the Collective Labour Agreement acknowledges that there will be strikes". Stabroek News. Guyana. January 6, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Scotiabank and NHL announce partnership renewal" (Press release). NHL. January 28, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Bundale, Brett (June 25, 2014). "Scotiabank wins naming rights for Halifax Metro Centre". The Chronicle Herald. Halifax. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Rebranded Scotiabank Centre Opens" (Press release). Halifax Regional Municipality. May 19, 2014.

- Hornby, Lance (August 29, 2017). "Air Canada Centre to be renamed Scotiabank Arena". Toronto Sun. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- Wallace, Lisa (June 18, 2013). "Scotiabank Place becomes Canadian Tire Centre". Global News. The Canadian Press. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Prize History". Scotiabank Giller Prize. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Krashinsky, Susan (October 14, 2015). "Scotiabank drops support for three more Toronto events". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Cineplex and Scotiabank Announce 10-Year Extension of SCENE Loyalty Program" (Press release). Scotiabank and Cineplex. November 6, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Scotiabank Hall". Brock University. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "2003 Public Accountability Statement". Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Scotiabank funds environment-related scholarships and international development work" (Press release). University of Waterloo. May 25, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "International Banking". Scotiabank. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Giarraputo, Joseph. "World's Best Emerging Market Banks 2011 in Latin America". Global Finance. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "The Banker Awards 2012 - Global and regional winners". TheBanker. November 29, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Scotiabank Trinidad and Tobago Named Bank of the Year 2013" (Press release). Scotiabank. November 29, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "World's Best Emerging Markets Banks in Latin America 2014". Global Finance. March 18, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Culbert, Andrew (October 18, 2013). "The Murder and the Money Trail". The Fifth Estate. CBC. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Sisler, Julia (October 19, 2013). "Scotiabank manager's death probe reveals multimillion-dollar fraud". CBC News. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Stewart, Art (November 11, 2013). "Murder of Bank Manager Tied to Fraud". Internal Auditor. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Acharya-Tom Yew, Madhavi (August 12, 2014). "Ontario court approves settlement deal for unpaid overtime at Scotiabank". Toronto Star. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Maurino, Romina (July 24, 2014). "Scotiabank agrees to settle in overtime lawsuit". CTV News. The Canadian Press.

- Critchley, Barry (July 13, 2005). "In defence of David Berry". National Post. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Finkle, Derek (June 1, 2008). "The Trader's Revenge". Toronto Life.

- Critchley, Barry (October 19, 2012). "Scotiabank explored fallout of cutting star trader's $15M pay months before he was fired, documents suggest". Financial Post.

- "In the matter of David Berry – Discipline Decision" (PDF) (Press release). IIROC. January 17, 2013.

- Critchley, Barry (January 16, 2013). "Former top Scotiabank trader cleared of allegations that led to his $100M wrongful dismissal lawsuit". Financial Post. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- Critchley, Barry (November 6, 2013). "Could Scotiabank's $55-million legal charge be linked to dismissed trader Dave Berry's lawsuit?". Financial Post. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "Automated Banking Machine (ABM)". Scotiabank. Archived from the original on May 7, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- "MultiLink Debit Network". J.E.T.S Ltd. July 25, 2004. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

Further reading

- Bank of Nova Scotia. 1932. The Bank of Nova Scotia, 1832–1932. Halifax: Bank of Nova Scotia.

- The Scotiabank Story: A History of the Bank of Nova Scotia, 1832–1982. by Joseph Schull

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scotiabank. |